OA not OK part 8: 170 to 1

Posted on 21 July 2011 by Doug Mackie

This is post 8 in a series about ocean acidification. Other posts: Introduction , 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, Summary 1 of 2, Summary 2 of 2.

Welcome to the 8th post in our series about the fundamental chemistry of ocean acidification. In this post we show that adding acid to seawater removes carbonate.

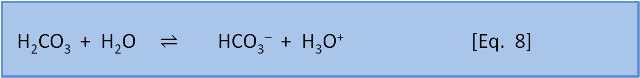

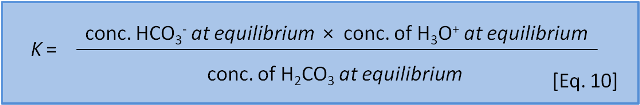

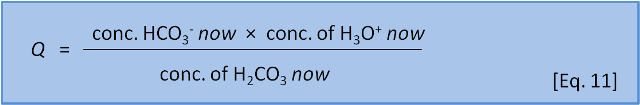

In the last post we introduced the concept of reaction coefficient to describe the state of a reaction relative to the equilibrium constant. For equation 8 we have the following expressions:

The direction in which a reaction responds to a disturbance is given by comparing Q to K. If Q < K then the reaction system is not yet at equilibrium and favours the right side (products) to reach equilibrium. If Q > K then the reaction system has 'gone past' equilibrium and favours the left side (reactants) to return equilibrium. (If Q = K the system is at equilibrium). K values cover a wide range and pK, analogous to pH, is more commonly used: pK = -log(K) and K = 10-pK.

Consider Equation 8 at equilibrium (i.e. Q = K) and ask what happens if we add some acid H3O+ to the system. By adding H3O+ we increase the products, thus increasing the numerator and therefore increasing Q so that now Q > K. The reaction system therefore favours the left side (reactants) and H2CO3 is produced.

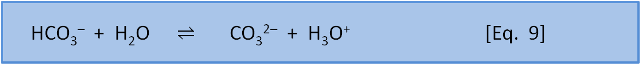

So far this sounds like Le Chatelier, but now we consider what happens with equation 8 and equation 9 occurring simultaneously.

For Eq. 8, in seawater at 10 oC, pK = 6.00. At the preindustrial ocean pH of 8.25, the equilibrium ratio of the left side, carbonic acid, to the right side, bicarbonate, is about 1:170 (depending on salinity). The calculation is 10-6.00 / 10-8.25. For Eq. 9, in seawater at 10 oC, pK = 9.19. At the preindustrial ocean pH, the equilibrium ratio of the left side, bicarbonate, to the right side, carbonate, is about 9:1 (the calculation is 10-9.19/10-8.25).

If we couple these reactions, we see that at typical ocean pH equation 8 produces a ratio of carbonic acid to bicarbonate (and carbonic acid to H3O+) of 1:170. If we do add a little acid (H3O+), then 170 parts of the acid stay as acid (H3O+) and only 1 part reacts to form carbonic acid and water. But equation 9 tells us that if acid is added then 1 part of the acid remains as H3O+ but 9 parts of the acid, and therefore some of the carbonate, are consumed to produce bicarbonate. At typical seawater pH, the response of the system to the addition of acid is dominated by the consumption of carbonate shown in Equation 9.

Now we can see that adding acid to the system does indeed push equation 9 to the left. Though a naive application of Le Chatelier's Principal to seawater chemistry gets the 'right' answer, this is only because of a fortuitous combination of the values for the equilibrium constants. (Seawater is in fact even more complex and there are many other competing reactions going on at the same time).

Thus, adding acid to the seawater-CO2 system massively changes the proportion of carbonate since it is consumed in the reaction. However, it hardly changes the proportion of bicarbonate since most of the carbon is already in the form of bicarbonate.

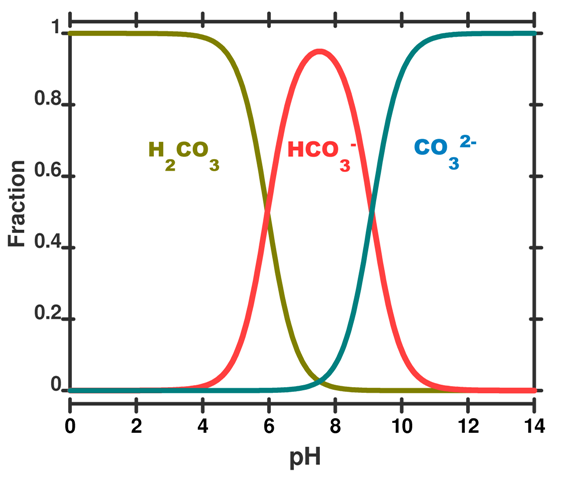

Calculations based on these concepts can be used to produce a speciation plot like Figure 3 which expresses the concentration of each species (expressed as a fraction of the whole) as a function of pH. In this figure the total sum of species containing carbon atoms is constant. What changes is the relative proportion of each species. We hasten to add that by adding CO2 to the ocean this is no longer true and the calculations become more difficult.

Figure 3. A speciation diagram for the carbonic acid system in seawater as a function of pH. The y-axis gives the fraction of each species present. A vertical line drawn at any pH value gives the relative proportion of each species. This plot is simplified to illustrate the concept; in real seawater several other factors like salinity, temperature and pressure are important.

We can run through some example calculations. Concentrations are given as moles per kg of seawater. For prior to the industrial revolution we have taken a pH of 8.25. Other input parameters are a total dissolved inorganic carbon concentration of 2100 x10-6 mol kg-1 (total dissolved inorganic carbon is the sum of the species described in post 5, temperature = 15 deg C, and the salinity = 35. Under these conditions, which are typical for the ocean, the concentration of H2CO3, HCO3– and CO32– would have been 10 x10-6 mol kg-1, 1830 x10-6 mol kg-1 and 260 x10-6 mol kg-1 of seawater, respectively (Roy constants used - see below).

The calculated values add to give the total dissolved inorganic carbon of 2100 x10-6 mol kg-1 and HCO3– and CO32– are roughly in a 7:1 ratio (the carbonic acid does not really contribute, because, as expected it is 170 times less than the HCO3–). Today, a after a decrease in pH to 8.14 – and an increase of 29% in the concentration of H3O+ – typical calculated concentrations of HCO3– and CO32– are about 1880 x10-6 mol kg-1 and 210 ×10-6 mol kg-1, respectively. You can see that HCO3– and CO32– are now roughly in 9:1 ratio. The concentration of carbonate CO32– has changed by –25% ((260-210)/210 × 100), but the concentration of bicarbonate HCO3– has only changed by 3% ((1880-1830)/1830) × 100.

We have made several simplifications here as the calculations are complex and beyond the scope of a blog post. Indeed, the full calculations are not encountered before postgraduate study. However, if you would like to try it yourself, you can download a program, written by one of us (KH) called SWCO2. It is available at the University of Otago. You will need to take some care – actual realistic values for the various entry parameters fall within a relatively narrow range.

If you do have a go yourself you will discover yet another layer of complexity: There are several sets of equilibrium constant, K, values to choose from. The reasons are complex and rest on the way that these values are determined experimentally and, though each set of values is internally consistent, each set uses a slightly different set of initial assumptions.

Now, just to further complicate things, we will introduce another equation:

K for this reaction is about 10-3. That is, the ratio of left to right is about 1,000:1. This means that, to a first approximation, seawater (dominated by HCO3–), has only a little bit of CO2 and CO32-. More importantly, it also shows that if we add CO2 to seawater, CO2 will spontaneously react with CO32– to form 2HCO3– because K for the reverse reaction is 103. In a later post we put some numbers to this concept.

Ocean acidification is caused by absorbance of atmospheric CO2 by seawater. We now see that this acidification of surface seawater is causing the removal of CO32–:

![]()

But why should this be a problem? We know from Equation 1 that calcification uses bicarbonate HCO3–, not carbonate CO32-. Why does it matter if some carbonate from the oceans is converted to bicarbonate? Won't that actually help the shellfish? We explain why not, and just where the acid is coming from, over the next few posts.

Written by Doug Mackie, Christina McGraw , and Keith Hunter . This post is number 8 in a series about ocean acidification. Other posts: Introduction , 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, Summary 1 of 2, Summary 2 of 2.

Arguments

Arguments

0

0  0

0 second summary post

second summary post

Comments