Climate Change Impacts on California Water Resources

Posted on 16 October 2010 by dana1981

California's water resources face significant strain on two fronts - a state population which is expected to grow from 35 to 55 million over the next 40 years, and a declining Sierra snowpack as a result of rising temperatures.

There is uncertainty regarding how total precipitation in California will change as the average planet and state temperatures continue to warm. Different climate models project anywhere from a modest decrease to a modest increase in net precipitation. Where the models agree is that less precipitation will fall as snow, and more as rain.

Temperature Projections

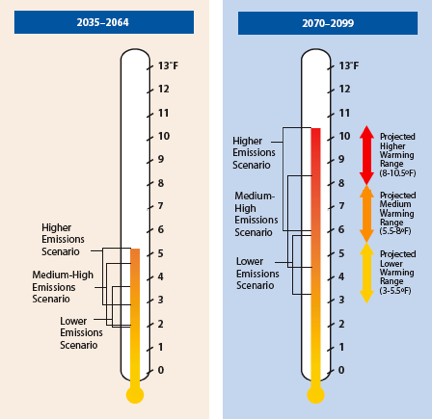

In 2003, the California Energy Commission’s Public Interest Energy Research program established the California Climate Change Center to conduct climate change research relevant to the state, a virtual organization with core research activities at Scripps Institution of Oceanography and the University of California, Berkeley. The Center performed a “Climate Scenarios” project (2005), which analyzed a range of impacts that projected rising temperatures would likely have on California. The project used three potential anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions scenarios (Figure 1) and three climate models with a range of climate sensitivity parameters to conclude that by 2099, average temperatures in California will rise by 3 to 10°F (1.7 to 5.5°C; Figure 2).

Figure 1: Projected CO2 emissions for the three scenarios considered by the Climate Scenarios project

Figure 2: Projected California warming under various emissions scenarios by 2064 (left) and 2099 (right)

Rainfall Replacing Snow

The Center's report summarizes the state water resource problem succinctly:

"Most of California’s precipitation falls in the northern part of the state during the winter while the greatest demand for water comes from users in the southern part of the state during the spring and summer. A vast network of man-made reservoirs and aqueducts capture and transport water throughout the state from northern California rivers and the Colorado River. The current distribution system relies on Sierra Nevada mountain snowpack to supply water during the dry spring and summer months. Rising temperatures, potentially compounded by decreases in precipitation, could severely reduce spring snowpack, increasing the risk of summer water shortages."

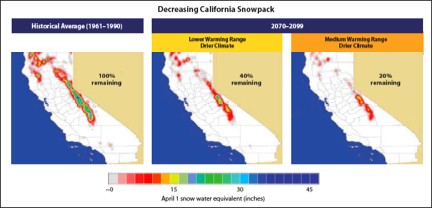

The study finds that the spring Sierra Nevada snowpack could decrease by 70 to 90% under the higher warming scenario. However, if emissions are significantly curbed and temperature increases are kept in the lower warming range, snowpack losses are expected to be only half as large as in the higher warming range (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Decreasing Sierra snowpack in low and high warming scenarios

As winter precipitation falls increasingly as rain rather than snow, reservoirs may need to be filled to a higher capacity in order to meet Californian water demand in the summer months when the Sierra snowpack no longer can. However, reservoirs also act as winter flood control, and thus filling them higher in the winter poses a greater threat for floods in the winter months.

New reservoirs may need to be constructed, but this increased storage will not come cheap. A study by Tanaka et al. (2006) found,

"California’s water supply system appears physically capable of adapting to significant changes in climate and population, albeit at a significant cost. Such adaptation would entail large changes in the operation of California’s large groundwater storage capacity, significant transfers of water among water users, and some adoption of new technologies."

Sea Level Rise

Aside from the obvious impacts to the coast of California, sea level rise also poses a threat to state water resources.

"An influx of saltwater would degrade California’s estuaries, wetlands, and groundwater aquifers. In particular, saltwater intrusion would threaten the quality and reliability of the major state fresh water supply that is pumped from the southern edge of the Sacramento/San Joaquin River Delta."

Agriculture

California has a $30 billion agriculture industry that employs more than one million workers. It is the largest and most diverse agriculture industry in the USA, producing more than half the country’s fruits and vegetables. Tanaka et al. found that agricultural water users are the most vulnerable to water resource changes as a result of global warming.

Schlenker et al. (2007) investigated the impact of climate change on irrigated agriculture in California and concluded,

"changes in water availability due to climate change hence have the potential to severely impact the value of farmland."

The study found that due to decreased runoff in late spring and early summer (due to increased precipitation falling as rain rather than snow, and a decreased Sierra snowpack, as discussed above), there will be less water availability when it is needed most, during the growing season. This will increase the demand for irrigation, putting more pressure on river and groundwater systems.

In terms of economic impacts, the study concludes that a reduction of one or two acre-feet of water per acre of land would result in a decrease in the value of the affected farmland of as much as $1,700 per acre.

Overall Water Sustainability

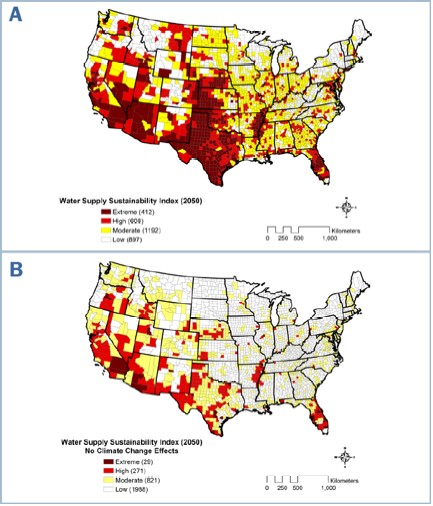

A study by Tetra Tech (2010) evaluated a Water Supply Sustainability Index (WSSI) which takes into account natural available precipitation; the extent of water development already in place; dependence on groundwater; the region’s susceptibility to drought; projected increases in water use; and the difference between peak summer demand and available precipitation, a measure of storage requirements. The projected WSSI throughout the USA in 2050 with and without climate change effects taken into account is shown in Figure 4. As you can see, climate change exacerbates an existing water problem in California, and many regions within the state face high to extreme water sustainability issues mid-century when climate change is taken into account.

Figure 4: Water Supply Sustainability Index in 2050 including (above) and excluding (below) climate change effects

The study found that water withdrawals in California are estimated to be greater than 100% of the available precipitation in 2050.

Conclusions

Overall, while there may not be a significant change in overall precipitation falling in California as the average temperature continues to rise due to anthropogenic global warming, the challenge is in coping with the transition as the precipitation falls more as rain than snow. Finding a way to store the rainfall as we lose nature's storage medium (the Sierra snowpack) will be difficult. Winter sports enthusiasts will also be adversely impacted by the decline in snowfall, as will the state economy. And the major agricultural industry of California is very vulnerable to these changes. A decrease in California agricultural production will not just impact the state and country, but the entire world.

The more we can reduce anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions, the less the planet and state will warm, and the easier it will be to cope with these changes. In fact as shown in Figure 4, in order to minimize water sustainability challenges nationwide, we must minimize the warming of the planet.

Arguments

Arguments

0

0  0

0

Comments