How Skepticism Can Protect You From Being Fooled

This is a re-post from the Thinking is Power website maintained by Melanie Trecek-King where she regularly writes about many aspects of critical thinking in an effort to provide accessible and engaging critical thinking information to the general public. Note: This article is the second of a two-part series on “doing your own research.” To read the first article click here.

This is a re-post from the Thinking is Power website maintained by Melanie Trecek-King where she regularly writes about many aspects of critical thinking in an effort to provide accessible and engaging critical thinking information to the general public. Note: This article is the second of a two-part series on “doing your own research.” To read the first article click here.

A real-life ghost story

On November 15, 1912, Mrs. H and her family moved into an old, rambling Victorian house. It had barely been occupied over the previous decade and was falling into disrepair. Lacking electricity, it was lit by gas lamps and always seemed dark.

It was only a few days after moving in that the family started to feel a sense of depression. The house’s thick carpeting absorbed the sounds of the family and servants, and the silence was overpowering.

Christ

One morning, Mrs. H heard loud footsteps overhead, and raced up the stairs to investigate. She went room to room searching for the source of the sound, even up to the next floor…. but there was no one in that section of the house.

Other members of the family heard sounds, too.

During the night, they heard furniture sliding across the floor, and dishes being moved around. Even long sighs or wails.

As she was dressing one morning, her four year-old boy ran to her room to ask why she called for him. But she hadn’t.

Only a couple of weeks after moving into the house, Mrs. H started to have severe headaches, and she was exhausted. She took iron pills and tried to take a nap each afternoon, but nothing seemed to work.

Each evening, as her husband ate fruit in the dining room before bed, he felt a presence, as if someone was watching him from behind. But when he turned around, no one was there.

The children lost their appetites and grew pale. So, in December, Mrs. H decided to take the children for a short vacation.

Alone in the house, her husband was kept awake at night by inexplicable noises. Several nights he heard bells ringing. He checked the doors. Once he thought it was the telephone. Another night he thought it was the fire department dashing up the street. But each time, he was unable to find the source of the sound.

In early January, Mrs. H and the children were back in the house, and the troubles continued. At night they heard loud footsteps, doors slamming, pots and pans being thrown around.

Her headaches returned, and she always seemed to feel cold and tired. The children caught colds that seemed to linger instead of improving. They spent most of their days in bed and refused to eat or even play. Her husband had terrible headaches. The servants had grown pale and listless. Even the houseplants died.

So, things were not going well. But no one had seen anything. Yet.

Mrs. H saw them first. One morning, a strange, dark-haired woman, dressed in black, came towards her, then disappeared. The woman appeared to her two more times.

On January 15, Mr. and Mrs. H went to the opera. As they slept that night, someone grabbed Mr. H by the throat to strangle him. He awoke in a violent coughing fit. At first, he thought maybe it had been a burglar. But everything was quiet. Then he thought Mrs. H was playing a joke on him, but she was in a deep sleep.

After breakfast the next morning, the children’s nurse confessed to her, “It has been a most terrible night. This house is haunted.”

She went on to say that the other servants had heard and seen things, too, but they didn’t want to disturb the family. But while they were at the opera the night before, the children were attacked. One of the children woke up, terrified and screaming about a “big, fat man” touching him. He spent the night in her bed for protection, but in the morning asked the nurse why she sat on him during the night.

The nurse told even more stories, of hearing an old man walking through the hallway, and feeling as if someone was following her. She said some nights the bed sheets were jerked off of her while she slept, and other nights the bed would shake. One night she woke up to see a young, thin woman with a large hat, and an old, bald man sitting at the foot of her bed. She was paralyzed with fear and unable to move until someone tapped on her shoulder.

Mrs. H interviewed all of the servants, and they all shared stories of loud noises, being followed, and seeing strange apparitions.

She contacted the previous residents of the house, and learned they all had had similar experiences, and the fear and exhaustion had driven them away from the house.

The inescapable conclusion was that their house was haunted.

Skepticism is evidence-based thinking

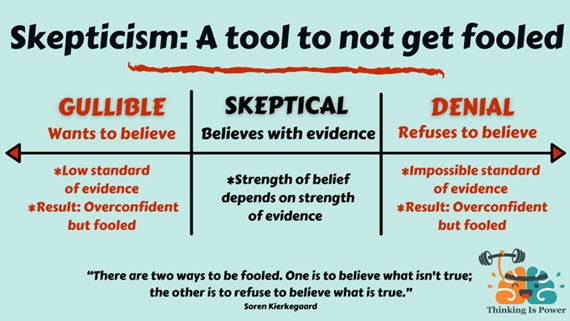

Skepticism is an empowering way to protect yourself from being fooled.

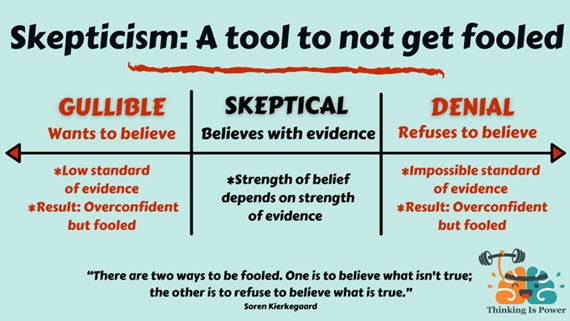

Skepticism has taken on a variety of connotations. To some, it’s synonymous with cynicism, or negativity. To others, it’s a refusal to accept scientific conclusions.

But skepticism is simply insisting on evidence before accepting a claim. It’s evidence-based thinking, and approaching all beliefs and assumptions with a healthy level of doubt.

We should be open-minded to the possibility of all claims, but not so open that our brains fall out. We don’t want to be gullible or be fooled.

However, extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.

And, if the evidence suggests we should change our minds, then we must be willing to do so, even if it’s uncomfortable. Failure to accept well-supported conclusions in the light of overwhelming evidence is not skepticism, it’s denial.

Essentially, skepticism is proportioning the strength of our belief with the strength and quality of the evidence, and it is the foundation of critical thinking and the scientific method.

Skepticism is also empowering. It’s a shield against those who seek to fool us, and a powerful tool to help us make better decisions.

We are inundated with information. But how can we know what’s true?

Consider the following claims:

- A supplement promises you can lose 30 pounds without dieting

- An email warns your bank account has been hijacked and wants your social security number

- A celebrity insists vaccines caused her child’s autism

- A social media post alleges a politician is running a child sex-trafficking ring

- A psychic asserts she can predict your future from reading your palm

- A friend maintains he cured his cancer with vitamins and a special diet

- A politician declares climate change is a hoax

When faced with such claims, a skeptic stops….really pauses….and says, “Wait, what? How do we know if that’s true?”

This simple shift in thinking is profound, because there can be real harm to falling for claims that aren’t true. It could cost you money, or even your life. So, before believing any of these claims, demand evidence.

But the most important and most difficult time to be skeptical is when we want something to be true. Claims that fit into our existing beliefs and biases have a way of bypassing our skepticism shield, making us more vulnerable to being fooled.

For example, in 1917, young cousins Frances and Elsie claimed to capture photos of fairies in their English garden. The photos caught the attention of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, trained physician and creator of the infamously rational detective Sherlock Holmes. Doyle was also a spiritualist, and he believed the photos were evidence that communication with the spirit world was possible. He was convinced the fairies in the photos were real. The photos were a hoax, of course, created from cardboard cutouts from children’s books.

For example, in 1917, young cousins Frances and Elsie claimed to capture photos of fairies in their English garden. The photos caught the attention of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, trained physician and creator of the infamously rational detective Sherlock Holmes. Doyle was also a spiritualist, and he believed the photos were evidence that communication with the spirit world was possible. He was convinced the fairies in the photos were real. The photos were a hoax, of course, created from cardboard cutouts from children’s books.

The point is we are all susceptible to being fooled.

Ghosts? Or something more sinister?

Whatever Mrs. H and her family were experiencing was real. It wasn’t the result of one person’s overactive imagination. Everyone in the house, including the children and servants had heard, seen, and felt things. And imagination doesn’t kill plants.

By the middle of January, the family had had enough. Mr. H told his brother about the terrifying events he and his family were experiencing in their new house….. about hearing footsteps and voices, feeling otherworldly touches, and seeing ghostly apparitions. He confessed how concerned he was about his family’s health.

His brother said he’d read an article about a family with similar experiences, and it wasn’t ghosts. They were being poisoned, and they should contact a doctor.

The next day their doctor made a house call. They told the doctor about the strange events everyone in the house was experiencing. As he walked through the home, he found two of the children in bed, and one of them lying on the floor, looking very ill.

Then he went to the basement, and discovered that the fumes from the old furnace, instead of going up through the chimney, were spewing into the house. He told the family if they spent one more night in the house, they might never wake again.

The cause of their symptoms – auditory and visual hallucinations, chest pressure, feeling of dread, and even touches – wasn’t supernatural after all. It was carbon monoxide poisoning.

Mr. and Mrs. H had their furnace fixed. The family recovered, and they never again reported seeing, hearing, or feeling any ghosts.

This is not to say that ghosts don’t exist. Like any good skeptic, we should be open to all claims. But we should also demand evidence. And ghosts are an extraordinary claim, which requires extraordinary evidence.

And yet there is real danger in believing you’re being haunted when you’re actually being poisoned.

The Take-Home Message

Skepticism is the best tool we have for discovering the truth. Doubt can be uncomfortable, but certainty is an illusion. We must be willing to subject all of our beliefs and assumptions to scrutiny… If something is true it will survive questioning. If it’s not true, we should be willing to change our minds.

Opponents may say skepticism takes the wonder out of the world. I disagree. Reality is awe-inspiring enough without believing in things that aren’t true. Some may think they don’t need skepticism, because they already know when they’re being fooled. However, be wary of overconfidence in our own experiences and knowledge.

Like Richard Feynman said, “You are the easiest person to fool.”

To Learn More

Ghost Village, A True Tale of a Truly Haunted House

This American Life, And the Call Was Coming from the Basement

TED, Carrie Poppy, A Scientific Approach to the Paranormal

NBC News, See Ghosts? There May Be a Medical Reason

Thanks to John Cook, Lynnie Bruce, and Anthony Trecek-King for their feedback.

Posted by Guest Author on Wednesday, 29 September, 2021

This is a re-post from the Thinking is Power website maintained by Melanie Trecek-King where she regularly writes about many aspects of critical thinking in an effort to provide accessible and engaging critical thinking information to the general public. Note: This article is the second of a two-part series on “doing your own research.” To read the first article click here.

This is a re-post from the Thinking is Power website maintained by Melanie Trecek-King where she regularly writes about many aspects of critical thinking in an effort to provide accessible and engaging critical thinking information to the general public. Note: This article is the second of a two-part series on “doing your own research.” To read the first article click here.