The IPCC has now released all three of the reports that comprise its 2014 Fifth Assessment of climate science. The first report tackled the physical changes in the global climate, while the second addressed climate impacts and adaptation, and the third looked at climate change mitigation. Ironically, after the second report was published, many media outlets argued that the IPCC was shifting its focus from global warming prevention to adaptation, seemingly unaware that its report on mitigation was scheduled to be published just a few weeks later.

Other media outlets have incorrectly argued that the IPCC reports conclude it's cheaper to adapt than avoid climate change. This error stems from the fact that the second report says about the costs of climate damages,

"the incomplete estimates of global annual economic losses for additional temperature increases of ~2°C are between 0.2 and 2.0% of income ... Losses are more likely than not to be greater, rather than smaller, than this range ... Losses accelerate with greater warming, but few quantitative estimates have been completed for additional warming around 3°C or above."

The third report then said about the costs of avoiding global warming,

"mitigation scenarios that reach atmospheric concentrations of about 450ppm CO2eq by 2100 entail losses in global consumption—not including benefits of reduced climate change as well as cobenefits and adverse side?effects of mitigation ... [that] correspond to an annualized reduction of consumption growth by 0.04 to 0.14 (median: 0.06) percentage points over the century relative to annualized consumption growth in the baseline that is between 1.6% and 3% per year."

The challenge is that these two numbers aren't directly comparable. One deals with annual global economic losses, while the other is expressed as a slightly slowed global consumption growth. While these numbers can be put in terms of their net impact on economic growth, the next problem is that the first is not a proper estimate of the costs of climate damages. The IPCC was only able to estimate the costs of climate damages for another 2°C warming, but limiting global warming to another 2°C will require substantial mitigation efforts.

Thus this estimate only tells us the costs of global warming in a scenario where we also act to significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions. As the second report notes, economists can't even accurately estimate the costs of climate damages in a business-as-usual scenario with global warming well above an additional 3°C. So how do we determine the economically optimal path?

To answer this question, I spoke with Cambridge climate economist Chris Hope, who told me that if the goal is to figure out the economically optimal amount of global warming mitigation, the IPCC reports "don't take us far down this road." To do this comparison properly, the benefits of reduced climate damages and the costs of reduced greenhouse gas emissions need to be compared in terms of "net present value." That's the sort of estimate Integrated Assessment Models like Hope's PAGE were set up to make.

According to Hope's model, the economically optimal peak atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration is around 500 ppm, with a peak global surface warming of about 3°C above pre-industrial temperatures (about 2°C warmer than present). In his book The Climate Casino, Yale economist William Nordhaus notes that he has arrived at a similar conclusion in his modeling research.

To limit global warming to that level would require major efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, but as the IPCC report on mitigation noted, that would only slow the global economic growth rate from about 2.3% per year to about 2.24% per year. According to these economic models, this slowed economic growth rate would be more than offset by the savings from avoiding climate damages above 3°C global warming.

Although the IPCC didn't make this comparison, these economic modeling results are consistent with its reports. As shown in the quote above, the second report was only able to estimate the costs of climate damages for an additional 2°C of global warming, and noted that beyond that point, the costs accelerate to a point where they become very difficult to estimate. Nordhaus has similarly noted,

"In reality, estimates of damage functions are virtually non-existent for temperature increases above 3°C."

Author and analyst Bjorn Lomborg of the Copenhagen Consensus Center has been the most prominent voice in incorrectly claiming the IPCC concluded that climate adaptation would be cheaper than mitigation. For example, he was interviewed in Rupert Murdoch's The Australian, and authored a piece in the Turkish Today's Zaman.

Both pieces are lemons for the same reasons. Lomborg argued,

"If we don't do anything, the damages caused by climate change will cost less than 2 per cent of GDP in about 2070. Yet the cost of doing something will likely be higher than 6 per cent of GDP, according to the IPCC report"

This compares the annual global economic losses figure for 2°C additional warming in the second report with the slowed global consumption growth figures to limit the warming to another 1°C in the third report. The problem is that this is an apples and oranges comparison. The former tells us the cost of climate damages in a scenario where we also take significant steps to slow global warming. It's not the cost of adaptation if we continue with business as usual, which would result in another 4°C warming by 2100 and incalculable damage costs.

Without the modeling tools used by economists like Hope and Nordhaus, these figures can't properly be put into an apples to apples comparison. Both the costs of mitigating and the costs of adapting to climate damages must be taken into account. I discussed this point with Lomborg and he agreed,

"I agree that the right way to look at the climate issue is to run integrated models and finding where the costs and the benefits are equal (so we don't underinvest in climate but don't over-invest either) ... However, the UN Climate Panel actively decided in 1998 to *not* do cost-benefit of climate."

So Lomborg and Hope agree that the IPCC reports don't allow for a simple comparison between the costs of global warming prevention and adaptation. Lomborg used the two figures discussed above to make the only comparison possible from the reports, but this looks to be an incorrect comparison, inconsistent with the results from economic models.

Lomborg also cherry picked the year 2070 to make his economic comparison between the costs of adaptation and mitigation. Why 2070? By that point, in a business-as-usual scenario the planet probably won't have warmed much more than 2°C compared to current temperatures. The problem with this cherry pick is that the world won't end in 2070; in fact, most of today's children will still be alive in 2070. If we continue on that business-as-usual path, global warming will continue to accelerate after 2070, past the point where economists can't even accurately estimate its accelerating costs. That's bananas.

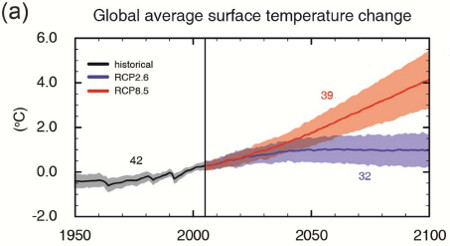

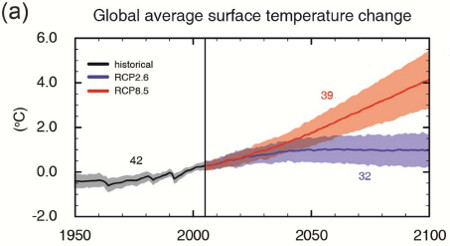

IPCC AR5 projected global average surface temperature changes in a business as usual scenario (RCP8.5; red) and low emissions scenario (RCP2.6; blue).

Another problem in this argument is that as shown in the second quote above, the IPCC estimates of the cost of reducing greenhouse gas emissions are "not including benefits of reduced climate change as well as cobenefits and adverse side?effects of mitigation." For example, the cleaner air and water, and associated health benefits that come with transitioning away from dirty high-carbon energy sources save money that the IPCC doesn't take into account. So the costs of avoiding global warming would in reality likely be even less than the estimated 0.06% per year slowing in the rate at which the global economy continues to grow.

Meanwhile, the IPCC noted that the costs of climate damages for just another 2°C warming "are more likely than not to be greater, rather than smaller" than its estimates. And if we don't take serious steps to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, we'll blow past 2°C warming into uncharted economic damage territory.

The bottom line is that economists can't even accurately estimate how much climate damages will cost if we fail to take serious steps to slow global warming. On the other hand, taking those steps can have a negligible impact on global economic growth. The IPCC report also makes the point that the longer we wait to reduce our emissions, the more expensive it will become. In determining that mitigating global warming is affordable, the IPCC used the following scenarios.

"Scenarios in which all countries of the world begin mitigation immediately, there is a single global carbon price, and all key technologies are available, have been used as a cost?effective benchmark for estimating macroeconomic mitigation costs"

This post has been incorporated into the rebuttal to the myth - adapting to global warming is cheaper than preventing it

Posted by dana1981 on Tuesday, 22 April, 2014

|

The Skeptical Science website by Skeptical Science is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. |