Figure 1: Map depicting the Labrador region of northeastern Canada

In 1534, famed explorer Jacques Cartier described Labrador as "the land God gave to Cain". This comparison is inevitably linked to Labrador’s rugged coastal landscapes dotted with deep inlets, fiords and rugged tundra. Culturally the region is steeped in complexity with three distinct indigenous populations intertwined with settlers and settler descendants.

In the north lies the Inuit settlement area of Nunatsiavut, where its predominantly Inuit residents are spread across 5 small communities. The Torngat Mountains National Park is located on the northern tip of Nunatsiavut where the tundra landscape forms part of the Arctic Cordillera and sustains small mountain glaciers along the coast (Brown et al, 2012; Way et al. Accepted). The Arctic treeline in the area descends as low as ~57°N due to the prevailing influence of cold polar water transported along the Labrador coastline by the Labrador Current.

In central and western Labrador, where the climate is considered subarctic, the indigenous population has historically been members of the Innu Nation who every year traveled north to George River to hunt the George River Caribou herd. Currently, there are two Innu communities (Natuashish and Sheshatshiu) which have a combined population of ~2,000 residents. The third aboriginal group in Labrador is largely made up of Inuit who have intermixed with the early European settlers and are now referred to as Nunatukavut (formerly Métis). Their traditional activities span the lands from Cartwright south along the Labrador coast where boreal forest meets coastal barrens.

Figure 1: Map depicting the Labrador region of northeastern Canada

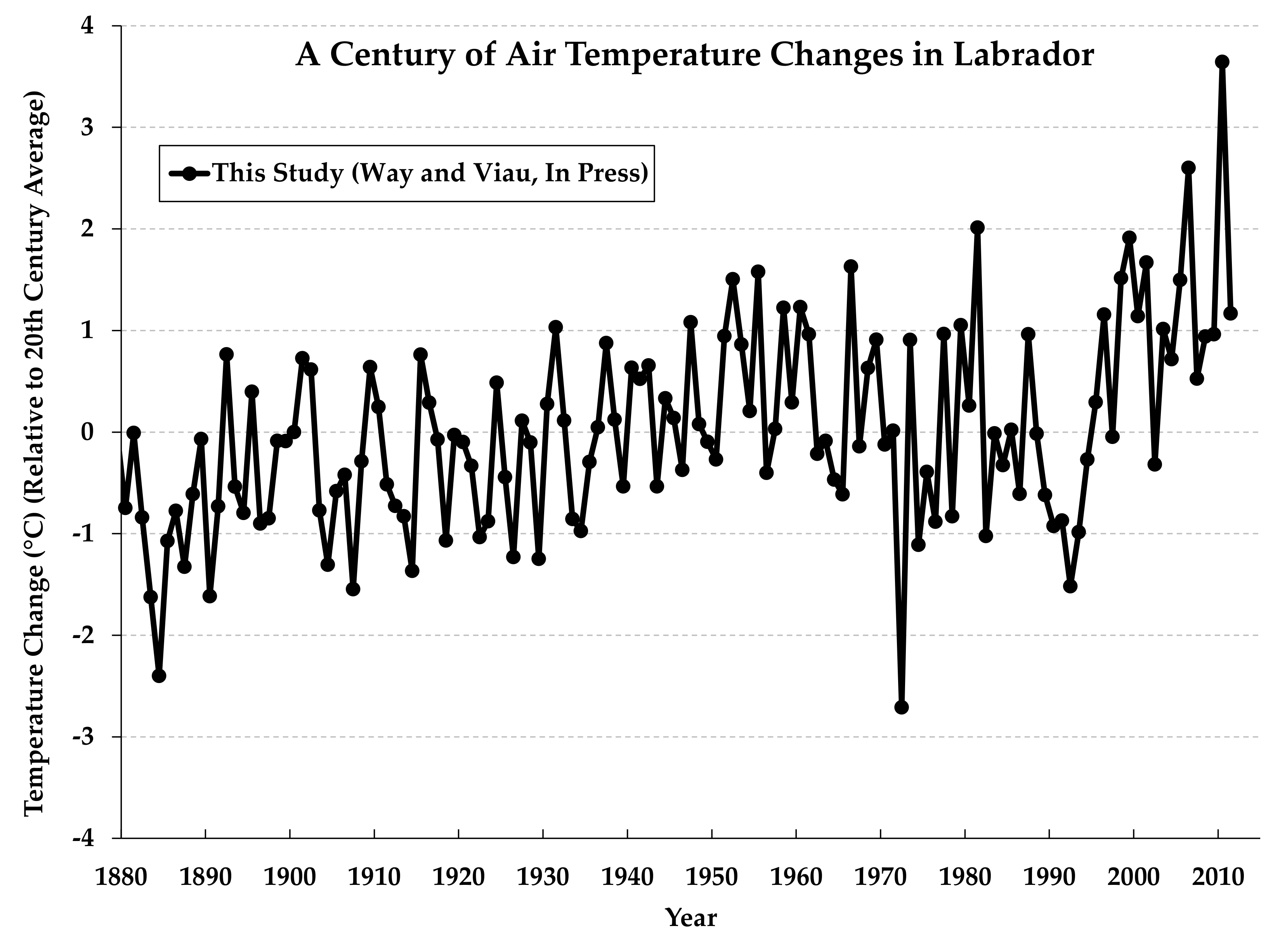

Throughout much of the modern era of global warming (post-1950s) air and ground temperatures in Labrador cooled, contrasting with many other regions (Allard et al. 1995; Banfield and Jacobs, 1998). This cooling continued until the late 1990s when regional air temperatures begin to warm rapidly (Brown et al. 2012; Way and Viau, In press; Figure 3).

In coastal Labrador, the human impacts of recent climate change have been ubiquitous for the Labrador Inuit who are reliant on sea ice and snow for accessing traditional hunting grounds and neighboring communities. These communities are only accessible by air and sea in the summer and air and snowmobile in the winter. Recent winter warming and local reductions in sea ice/snow cover have reduced access for Inuit to traditional fishing and hunting grounds and also neighboring communities (Wolf et al. 2013).

Vulnerability assessments have identified food security as being a key area in which Labrador’s coastal communities will be susceptible to climate change in the future, which is expected to be on the order of 3°C by 2038-2070 (Finnis 2013). However, the region’s geographic location makes it intrinsically linked to climate variability in the North Atlantic, complicating future climate projections (D’Arrigo et al. 2003).

Figure 2: Photograph of me holding the Labrador flag during a field season studying glaciers in the beautiful Torngat Mountains National Park.

As a Labradorian and Nunatsiavut Beneficiary, I am proud to say that I have spent the past 4 years working on research in Labrador - studying its climate, glaciers and now permafrost. Recently, a colleague and I completed a study (Way and Viau, In press) which examines the historical evolution of Labrador air temperatures over the past century.

According to three data sources, Labrador air temperatures have increased by ~1.5°C since the 1880s when the earliest observations were made by Moravian missionaries along the Labrador coast (Demarée and Oglivie, 2008). Air temperatures have substantially increased in all seasons with the greatest change occurring in the Winter and the least change occurring in the Fall. The single warmest year in the record (2010) was 3.4°C above the 20th century average and included an anomalously warm winter (+6.8°C) that had profound impacts.

Figure 3: Changes in Labrador air temperatures over the past century (1881-2011) derived from the Berkeley Earth Surface Temperature dataset by Way and Viau, (In press).

That year, communities in northern Labrador struggled to access traditional lands due to anomalously low snow cover and weak ice conditions prompting many concerns including about food security under a warming climate. From a personal perspective, I remember that year clearly. I had traveled back to Labrador in February to spend a week hunting and snowmobiling but soon after I arrived the weather changed to above zero temperatures leading to widespread snow melt and degradation of ice conditions.

For me, these conditions simply affected my recreation activities - but for people in coastal Labrador they prompted concerns about accessibility, food security and travel safety. Over the past decade poor ice conditions have become the number one concern relating to climate change for Inuit and non-Inuit Labradorians alike.

Figure 4: Photograph of poor ice conditions in central Labrador during January of 2011. In normal winters at this time of the year the river is completely frozen and used for accessing cabins and hunting grounds via snowmobile.

From an ecological perspective, the impacts of climate change in Labrador are clearly evident with small mountain glaciers receding (Brown et al. 2012) and treeline expansion occurring (Simms and Ward, 2013). Ground surface temperatures appear to be warming (Hachem et al. 2009) and boreholes indicate extreme increases in subsurface temperatures relative to the past several hundred years (Chouinard et al. 2007). A recent initiative launched by the University of Ottawa called the Labrador Permafrost Project aims to document regional permafrost changes in response to a warming climate as well (e.g. Way and Lewkowicz, 2013).

Although regional warming is evident, it is important to remember that directly linking individual warm (or cold) events to climate change is fraught with challenges – especially in a region like Labrador which has a volatile climate. For example, using a combination of modelling approaches, Way and Viau (In press) show that nearly half of the 2010 event is associated with natural variability. This result is in agreement with those of Cohen et al (2010) who link exceptional winter warmth in the eastern Canadian Arctic during 2010 to natural climate variability in the North Atlantic (negative AO/positive AMO) which impacted most of northeastern Canada.

However, the recent increases in Labrador air temperatures is consistent with anthropogenic global warming and suggests that warming is effectively increasing the likelihood of extreme warm events such as that of the winter of 2010 (Way and Viau, In press). While the 2010 event itself may not be directly attributable to climate change, the impacts of that anomalous year provide a snapshot in time representing what Labrador's climate may be like in 50 years.

Figure 5: University of Ottawa permafrost monitoring station in north-central Labrador established as part of the Labrador Permafrost Project. This station measures air temperature, ground surface temperature, subsurface ground temperature and snow depth.

For those of us who have studied recent changes in the Arctic, it is abundantly clear that the data support what Inuit elders have been saying for many years. That climate change is occurring rapidly and that the most profound impacts will be felt by those in the north. There will always be those who try to underplay these recent changes but inevitably with each passing year it becomes more obvious that denial is an unsupportable position.

Climate is a cultural entity for those who rely on the land - it is both harsh and unforgiving yet comforting and providing. Traditional knowledge is telling us that the Arctic is less predictable than it once was, but there is one prediction that remains certain - that the climate as it once was will be simply remembered as a story passed on to future generations.

Posted by robert way on Wednesday, 20 August, 2014

|

The Skeptical Science website by Skeptical Science is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. |