This is a guest post by Lawrence Hamilton, Senior Fellow at the Carsey School of Public Policy, University of New Hampshire.

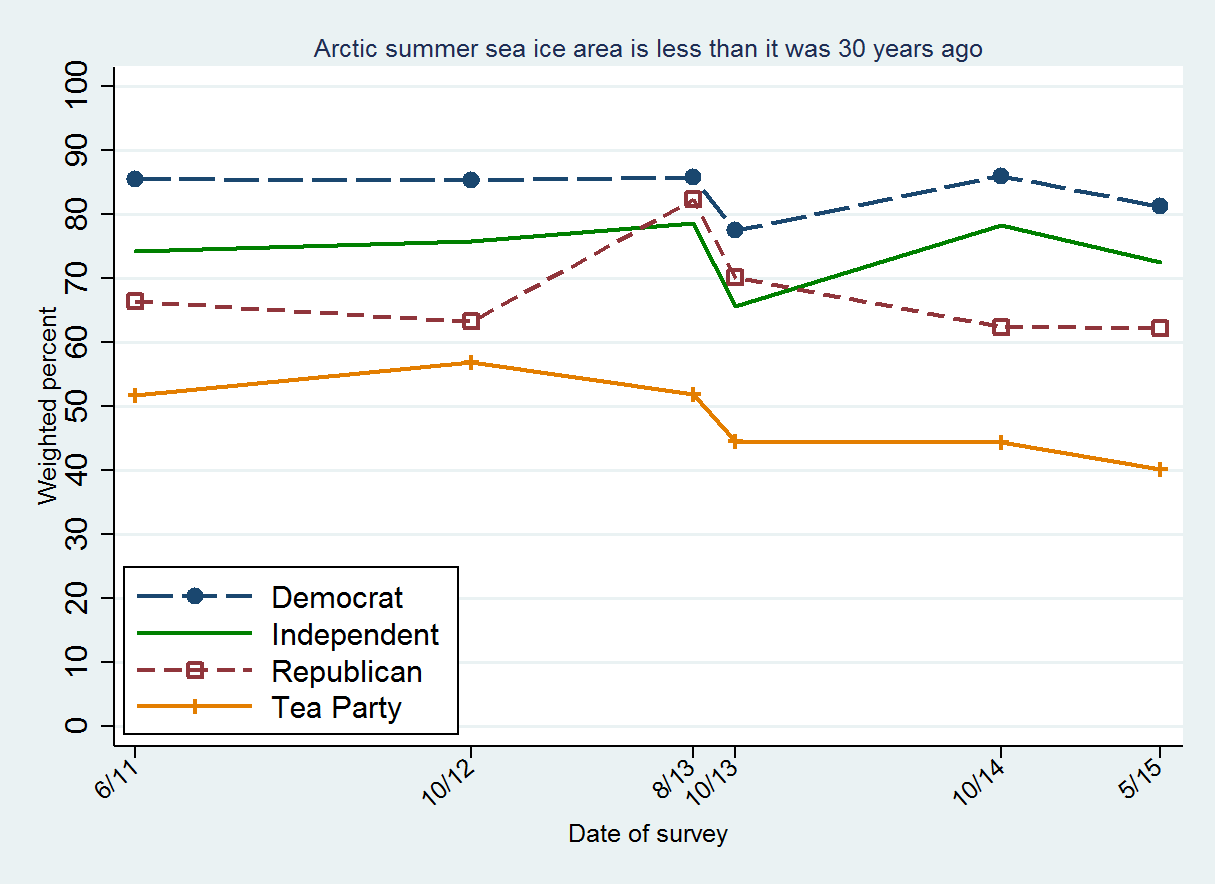

What do people know about the polar regions? Who knows what? New survey research recently published in Polar Geography offers un-reassuring answers. On some purely factual questions, people responded as if asked for their political opinions. For example, the graph below tracks responses to a question about the area of Arctic sea ice.

Figure 1: Correct responses by political party to the survey question: Which of the following three statements do you think is more accurate? Over the past few years, the ice on the Arctic Ocean in late summer – covers less area than it did 30 years ago; declined but then recovered to about the same area it had 30 years ago; or covers more area than it did 30 years ago.

This graph shows the percentage of “less area” responses, which are unambiguously correct — late-summer sea ice area in recent years has been more than a million square kilometers less than in the 1980s. Our political indicator, developed for an earlier paper, separates Tea Party supporters from other groups. Democrats and Tea Partiers stand about 35 points apart in their beliefs about the area of Arctic sea ice. Independents and non-Tea Party Republicans average just 7 points apart. The data are from 3,149 interviews on six New Hampshire (US) surveys, June 2011 to May 2015.

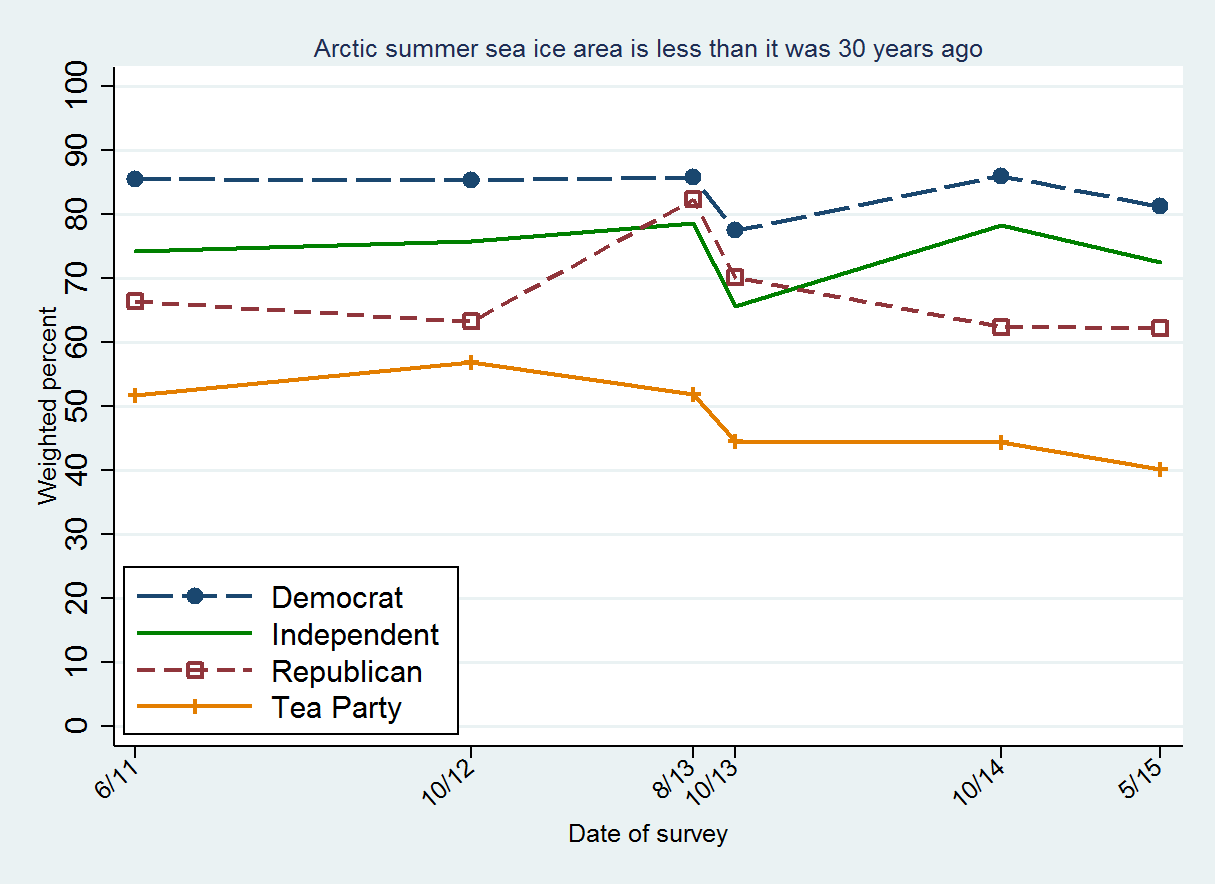

Certain other factual questions such as whether atmospheric CO2 levels have increased show similar political patterns. Partisan divisions are even wider on a more speculative question about the effects future Arctic warming might have on mid-latitude weather.

Figure 2: Responses (percentage choosing “major effects”) by political party to the survey question: If the Arctic region becomes warmer in the future, do you think that will have – no effects on the weather where you live; minor effects on the weather where you live; or major effects on the weather where you live?

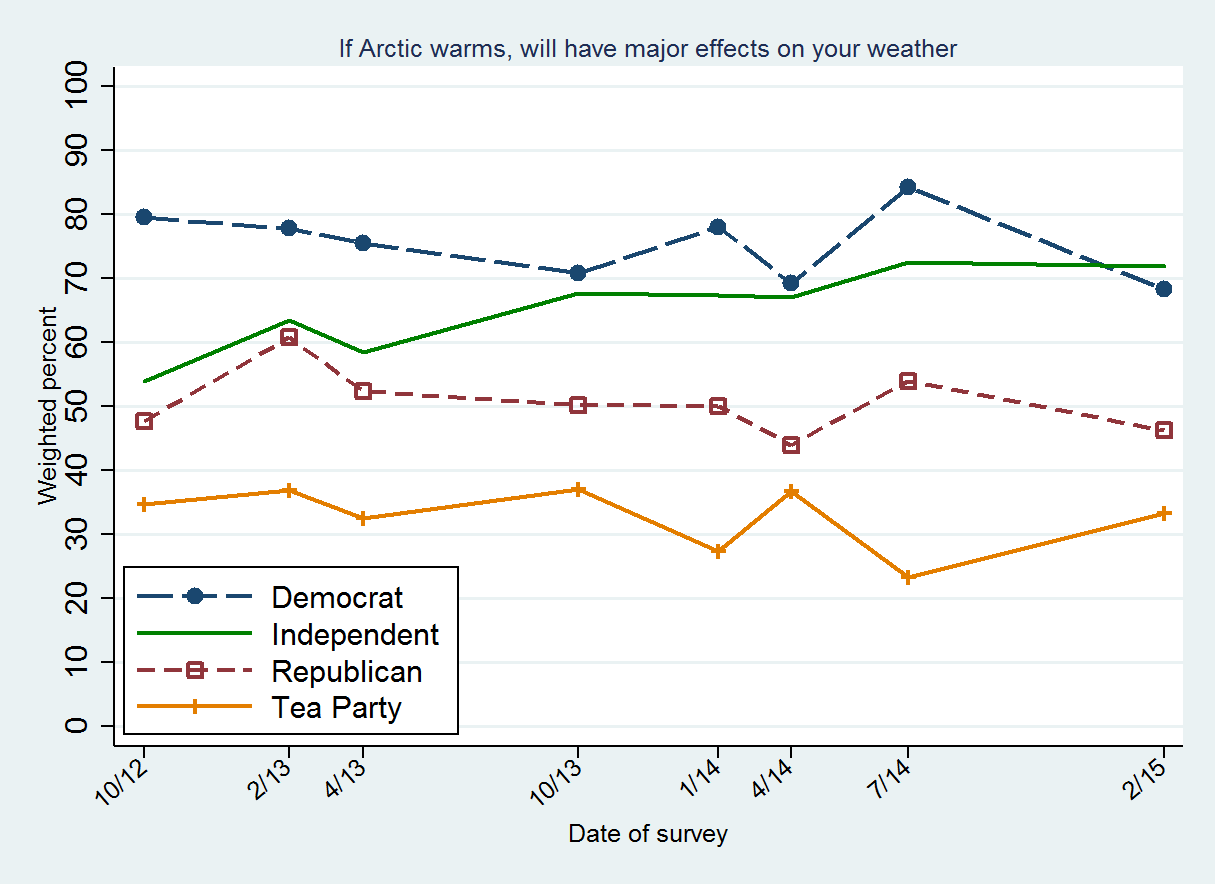

These questions have answers that are guessable (correctly or not) from what you personally believe about climate change. Consequently, the responses behave like opinions. Another kind of question has answers that are not guessable from climate-change beliefs. Bar charts below show three examples, and a knowledge score defined as the number correct (0–3). Percentages are based on 1,570 New Hampshire survey respondents who were asked all three of these belief-neutral questions.

Figure 3: Responses to three “belief-neutral” survey questions about polar knowledge.

A. Which of the following possible changes would, if it happened, do the most to raise sea levels? – melting of sea ice on the Arctic Ocean; melting of land ice in Greenland and the Antarctic (correct answer); or melting of glaciers in the Himalaya and Alaska.

B. Which of these best describes the North Pole? – ice a few feet or yards thick, floating over a deep ocean (correct answer); ice more than a mile thick, over land; or a mainly rocky, mountainous landscape.

C. Which of these best describes the South Pole? – ice a few feet or yards thick, floating over a deep ocean; ice more than a mile thick, over land (correct answer); or a mainly rocky, mountainous landscape.

D. Number of correct answers (0-3).

Only 37% knew or guessed that the North Pole is on sea ice, and even fewer (29%) recognized that melting of Greenland and Antarctic land ice, rather than Arctic sea ice, could potentially do the most to raise sea levels. Forty-six percent correctly placed the South Pole on thick ice over land, but since many said the same about the North Pole, that might partly reflect a bias toward “thick ice over land.” Two-thirds of our sample got no more than one answer on these three-choice questions correct.

Many surveys have included two standard questions about climate change:

1) How much do you feel you understand about global warming or climate change? – a great deal; a moderate amount; only a little; or nothing at all?

2) Which of the following three statements do you personally believe? – climate change is happening now, caused mainly by human activities; climate change is happening now, but caused mainly by natural forces; climate change is not happening now.

The second, “personally believe” question yields stark and persistent divisions, analyzed in several papers (2011, 2012, 2015). The “understanding” responses to the first question are striking for a different reason: so many people (78% in New Hampshire) say they understand either a moderate amount or a great deal about climate change.

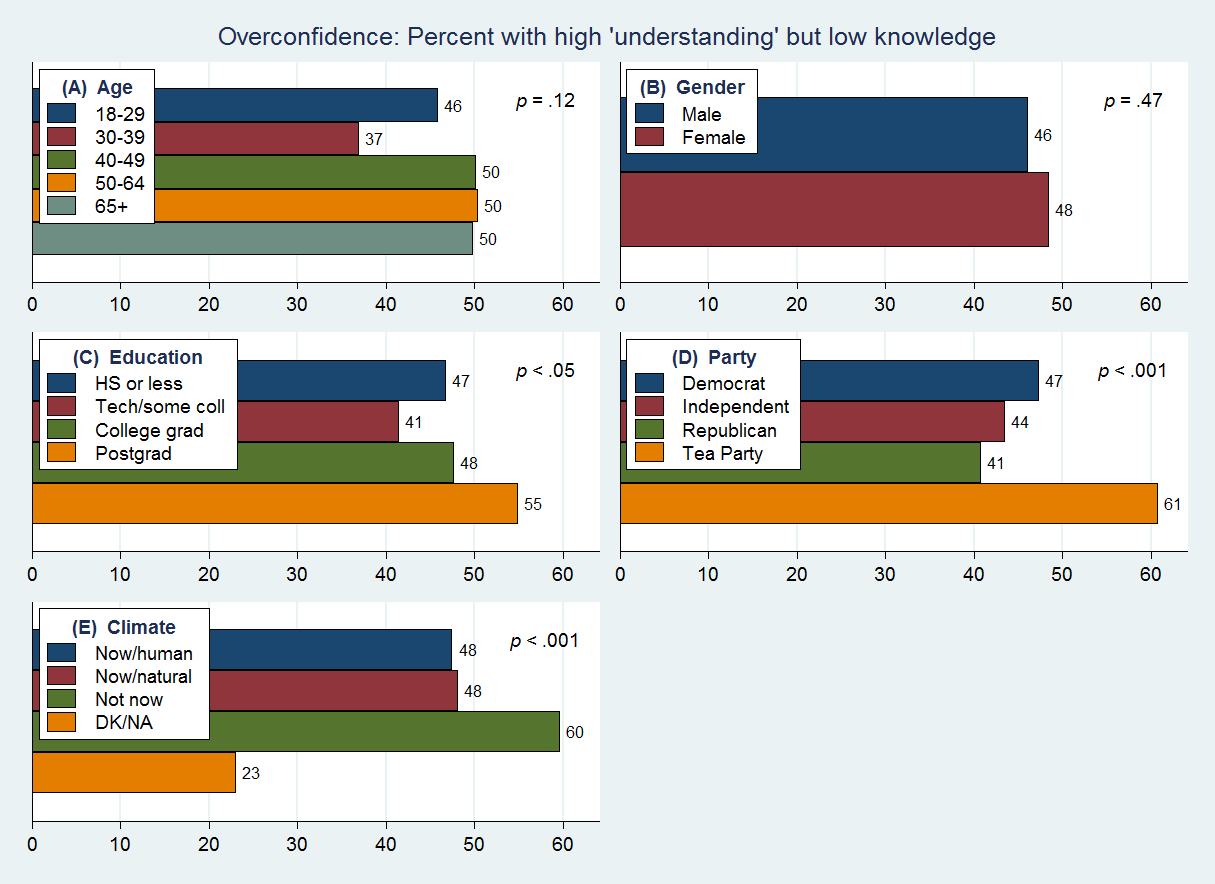

Our knowledge score provides a reality check using a few basic but neutral facts that anyone paying attention to climate discussions (or a globe) ought to know. Overconfidence, defined as moderate or great “understanding” combined with low knowledge (no more than one answer correct), characterizes almost half our sample. Bar charts below show rates of overconfidence within subgroups.

Figure 4: Percentage of overconfident respondents, or those reporting moderate/great understanding but having low knowledge scores.

Overconfidence is not significantly related to age or gender (Fig. 4A and B). It is somewhat more prevalent among people with postgraduate education (Fig 4C), but larger differences occur by political party (Fig 4D) and climate-change beliefs (Fig. 4E). Democrats, Independents and Republicans are not far apart, whereas Tea Party supporters significantly more often (61%) combine high self-assessed understanding with low knowledge. Rates of overconfidence are similarly high (60%) among those who think climate change is not happening.

The false sense of understanding has ideological roots. Previous studies found that Tea Party supporters report the highest levels of understanding about climate change (Leiserowitz et al. 2011, pdf; Hamilton and Saito 2015). That occurs in these surveys as well: 43% of Tea Party supporters, compared with just 18% of Republicans, 21% of Independents, and 31% of Democrats say they have “a great deal” of understanding about climate change. Polar knowledge scores, however, point in the opposite direction: only 27% of Tea Party supporters, compared with 31% of Republicans or Independents, and 39% of Democrats, answered two or three questions correctly.

These results support a common-sense view that we need a mix of approaches to address people with different configurations of knowledge and certainty. Communicating the strength of scientific consensus might be most helpful as a heuristic for people without much science knowledge and without strong preconceptions. Detailed information such as Skeptical Science counter-arguments could help those who know some science already, and are open to learn more. To make inroads against what Kraft et al. 2015 term the “hyperskepticism toward scientific evidence among ideologues,” more culturally-tailored approaches are needed. The pace of polar change gives context and urgency to communication efforts.

Posted by Guest Author on Friday, 10 July, 2015

|

The Skeptical Science website by Skeptical Science is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. |