This is a re-post from Carbon Brief by Simon Evans

China is aiming to peak its carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions "around 2030" and will make "best efforts" to peak early, its climate pledge to the UN confirms.

China's intended nationally determined contribution (INDC) includes a new target to reduce its carbon intensity by 60-65% of 2005 levels by 2030. Carbon Brief analysis suggests the top end of this range would see CO2 peaking in 2027. China also says it will source 20% of its energy in 2030 from low-carbon sources.

The announcement, which adds to existing Chinese commitments, came on a busy day on Tuesday for climate pledges. South Korea, Serbia and Iceland all filed INDCs with the UN, bringing the share of global emissions covered by pledges to nearly 56%. Tuesday also saw Brazil and the US announce new commitments to renewable energy at a joint summit in Washington.

As the world's largest emitter responsible for nearly a quarter of global greenhouse gas emissions, China's announcement is the most significant. Amber Rudd, UK energy and climate change secretary, said it was a sign that momentum was building for a deal in Paris this December. We'll look at what China says it wants from that deal in a moment.

China become the world's largest emitter in 2005-6 (red line, below), after overtaking the EU in 2003 and the US in 2005. It rapidly eclipsed the world's other major economies through coal-fuelled expansion and double-digit economic growth.

Energy-related CO2 emissions in major economies and the rest of the world, 1970-2014. Source: BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2015. Chart by Carbon Brief.

However, emissions and coal use in China stalled in 2014, following a decade-long expansion, with GDP growth easing to around 7%. China is still adding to its coal-generating capacity, so the potential remains for coal use to rebound and expand. The government has set a generous cap on coal use that will apply from 2020, but it is far above current levels.

The slow-down in emissions with continued economic growth is a result of structural changes in China's development. It says it is pursuing "ecological civilisation", and hopes to work with other nations to "build a beautiful homeland for all human beings". Its climate goals are part of this effort.

Apart from aiming to peak carbon emissions around 2030, China's INDC extends its existing carbon intensity target, on the emissions required to generate a unit of GDP. China has long set intensity targets, and though it has a good record of meeting them, some analysts areconcerned it might fall short on the current round, which run to the end of 2015.

It now aims to reduce carbon intensity by 40-45% of 2005 levels by 2020 and by 60-65% in 2030. This implies annual improvements of 3.4-3.9% to 2020 and 3.1-5.2% in the following decade.

Li Shuo, senior climate and energy policy officer for Greenpeace East Asia tells Carbon Brief that China will "almost certainly" reach the top end of its intensity target for 2020.

Translating the intensity target into emissions requires assumptions about the path of Chinese economic growth. Carbon Brief analysis, based on GDP projections from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, shows CO2 emissions could peak in 2027 at around 12.7 billion tonnes (red line, below), up from 9.8Gt in 2014.

Millions of tonnes of CO2 emissions in China. Historical data from the BP Statistical Reviewand the World Bank. Future emissions estimated based on OECD projections for economic growth and steady progress towards the upper (65%) or lower (60%) end of China's carbon intensity target for 2030. Chart by Carbon Brief.

Some analysts believe China will peak its emissions by 2025 or before. This could be followed by a long emissions plateau.

There is great potential for cost-effective energy efficiency improvements in China, particularly in industry, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). If exploited, the IEA says this Chinese CO2 emissions would peak by the early 2020s.

Others suggest non-CO2 emissions — and China's total emissions — may continue to grow even if CO2 reaches a peak. There is limited detail on other greenhouse gases in the Chinese pledge.

It has vague targets to "enhance" efforts to capture methane in oil and gas fields and to "control" methane emissions from rice paddies. It also aims to phase down use of HCFC-22, a potent greenhouse gas, and to "achieve effective control" of another, HFC-23.

There is also a promise to "vigorously enhance afforestation" and increase the stock of biomass stored in forests by 4.5bn cubic metres by 2030, against 2005 levels. The pledge does not explain how this might help to reduce net emissions. However, trees are thought to absorb around a tonne of CO2 per cubic metre of biomass.

China says it has met an earlier pledge on forest stocks by adding 2.2bn tonnes between 2005 and 2014, while expanding its forested area by 21.6m hectares — roughly the area of the UK. Over the 16 years to 2030, therefore, China's forest stock pledge could see an additional 140MtCO2 absorbed by forests each year, slightly less than 10% of total CO2 emissions.s

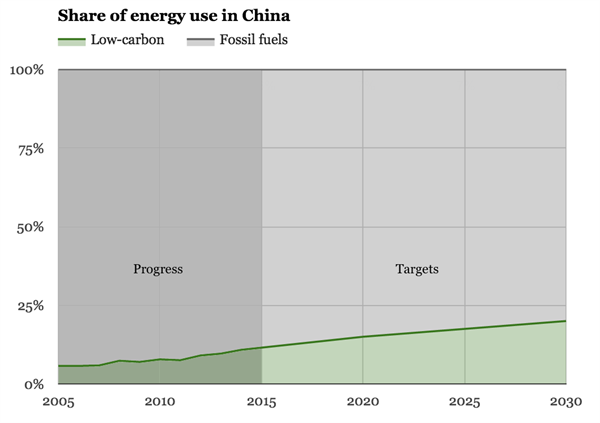

China's climate pledge also repeated its existing goals to source 20% of its energy needs from non-fossil sources by 2030, up from 15% in 2020. This would imply roughly maintaining the rate of progress seen since 2011.

This expansion has been based on a massive build-out of renewables, particularly hydro, with China adding nearly half of the additional renewable power generated globally over the past decade. It has targets to raise hydro capacity to 420 gigawatts (GW) in 2020, while adding 18GW of nuclear, doubling wind to 220 GW and doubling solar to 70GW, all between 2015 and 2020.

Share of China's energy needs met by low-carbon sources, including nuclear, hydro, wind and solar. Source: BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2015 and China's INDC. Chart by Carbon Brief.

To achieve these ambitions, China has been investing more in renewable energy than the US, EU and Japan put together. Combined low-carbon power capacity could expand by 800-1,000GW between now and 2030, according to the World Resources Institute.

China says it wants a legally binding UN climate deal from Paris that is "balanced and ambitious", guided by the climate convention principles of equity and "common but differentiated responsibilities". This means the agreement should require all parties to limit or reduce emissions during 2020-2030, China says, but with developed countries taking the lead.

It repeats calls on climate finance and technology transfer made jointly with the BASIC group of emerging economies over the weekend. China wants the core Paris agreement to include elements on cutting emissions, adapting to climate change, financing the efforts of poorer nations and transferring low-carbon technologies.

It says it will establish a Fund for South-South Cooperation on Climate Change to provide "assistance and support, within its means" to other African nations, small island states and other developing countries. This breaks with previous tradition, where developed nations are the only ones that have been obliged to provide climate finance.

Though China's language on the Paris deal is detailed, it leaves plenty of wriggle room around the details of which parts should be legally binding, on who, and in what way. And in common with all other climate pledges so far, its INDC remains well short of what would be required to meet the agreed 2C target for avoiding dangerous climate change.

Liz Gallagher, programme leader on climate diplomacy at thinktank E3G says:

"This submission is critical to building momentum towards a climate deal in Paris. There is still time for China to ramp up ambition. These offers are the floor, not the ceiling of a deal in Paris."

In the corridors of the Bonn climate talks in June, there was a sense that, perhaps in contrast to the ill-fated Copenhagen talks in 2009, China is strongly in favour of a deal in Paris. To the extent that it has been playing hardball on some issues, it is more a case of attempting to extract concessions rather than walking away completely.

So the Chinese pledge is being received as a positive, yet insufficient momentum-building step towards a deal — and just maybe, leaving the door open for 2C.

Posted by Guest Author on Saturday, 18 July, 2015

|

The Skeptical Science website by Skeptical Science is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. |