Figure 4, Global Energy Subsidies 2011-2015, IMF Working Paper WP/15/105

This is a re-post from Carbon Brief

The opening day at COP21 in Paris has seen a blizzard of announcements and speeches.

More that 150 world leaders travelled to the French capital to show their support for the much-anticipated climate conference, which aims to secure a global deal on tackling climate change in the post-2020 period.

Ban Ki-moon, the UN secretary general, opened the leaders summit by saying: “This is a pivotal moment for the future of your countries, your people and our common home. You can no longer delay.”

Carbon Brief is in Paris for the next two weeks covering the event. Here, we take a closer look at the key announcements made on Day 1.

Barack Obama said that the US, along with other nations, would pledge new money today to the Least Developed Countries Fund (LDC Fund) — a fund that is specifically responsible for reducing vulnerability in the world’s poorest countries (see below for more details). He said that new money would be pledged tomorrow towards risk insurance initiatives “that help vulnerable populations rebuild stronger after climate-related disasters”.

Obama laid out his priorities for the new deal, which he said should be an “enduring framework for human progress”.

The agreement, he said, should build in ambition through “regularly updated targets”, set at a national level, which takes into account the differences between different nations. The start of this process has already taking place, with the INDCs submitted by almost all UN nations over the course of the year.

He also emphasised the need for a strong transparency system, and the need to support countries that don’t have the capacity to report their progress on meeting their climate commitments.

Perhaps one of his most significant statements regarding the shape of the future climate deal was his reference to making sure resources “flow to the countries that need help preparing for the impacts of climate change we can no longer avoid” — a reference to the controversial issue of loss and damage in all but name.

He particularly highlighted the plight of the small island states — a group of nations with whom he will meet before leaving the conference. It is possible that the forthcoming donation to the LDC Fund could be a nod towards loss and damage. The US already softened its stance on the issue during a round of negotiations in Bonn in September.

President Xi Jinping repeated the country’s pre-existing target of peaking emissions by 2030, telling delegates that China has the “confidence and resolve to fulfil our commitments”.

His newest announcement was the fleshed out details of how China intends to spend the ¥20bn ($3bn) it announced in September. Among other things, China will launch 100 mitigation and adaptation projects in developing countries, and help them to build up financing capabilities.

He also promised that “ecological endeavours” would “feature prominently” in China’s forthcoming 13th five-year plan, a blueprint for its development in 2016 to 2020. This is due to be finalised in March.

He also spelled out some of China’s priorities for the UN climate deal that countries are in Paris to negotiate. While he said that the principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities” should be adhered to, he stressed that the outcome is a regime that should apply to everyone, within their capabilities.

“All countries, developed countries in particular, should accept shared responsibility for win-win outcomes,” he said. Such language is far more conciliatory than that adopted by China’s negotiating bloc just last month, which took pains to stress thecontinued divisions between the rich and poor nations.

Narendra Modi, the Indian prime minister, and Francois Hollande, France’s president, launched an International Solar Alliance, an Indian initiative dedicated to the promotion of solar energy. It aims to “significantly augment solar power generation”, says a declaration handed out at a press conference.

The alliance will aim to foster cooperation and collaboration between solar-rich nations. A working paper lists 121 “prospective member [countries]”. It says solar can “transform lives” for people living without power in off-grid rural & urban fringe areas.

Writing in the Financial Times, Modi said the aim was “to bring affordable solar power to villages that are off the grid”.

India will provide $62m over five years to 2020/21, including in-kind support such as land and $27m of funding towards running costs.

The alliance hopes to mobilise “more than $1,000bn of investments that are needed by 2030 for the massive deployment of affordable solar energy”. An international steering committee will hold its first meeting on 1 December.

Speaking at the launch of the alliance, Hollande said: “We can no longer accept the paradox…that the countries with the largest solar potential have only a small proportion of solar generation.”

Coal, oil and gas have been the foundation of wealth in the past but are the energies of yesterday, Hollande said. “Wealth tomorrow will come from new energies that will be developed everywhere and, namely, solar”.

Modi told the launch many nations had long placed special cultural significance in the sun. He said: “The world must turn to sun, the power of the future…There is already a revolution in solar energy…Costs are coming down and grid connectivity is improving. It is [bringing] the dream of universal electricity access [closer].”

John Key, the prime minister of New Zealand, used the first day of COP21 to officially present the Fossil-Fuel Subsidy Reform Communiqué to Christiana Figueres, the executive secretary of the UNFCCC. He was joined by the prime ministers of Denmark, the Netherlands, Sweden and Norway.

The communique represents the views of 37 countries, including Canada, France, Germany, Mexico, the US, the UK, New Zealand and the Philippines. It is also endorsed by “23 global companies with combined revenues exceeding $170bn” and organisations, such as the International Energy Agency, the OECD and World Bank.

The communique calls for three “interrelated principles”:

It adds: “We invite all countries, companies and civil society organisations to join us in supporting accelerated action to eliminate inefficient fossil-fuel subsidies in an ambitious and transparent manner as part of a major contribution to climate change mitigation.”

John Key said that a third of global emissions between 1980 and 2010 had been driven by fossil fuel subsidies. He added that the world spends around US$500bn a year keeping domestic fuel prices artificially low: “[Ending such subsidies would] free up resources to invest in low-carbon energy. They are a huge obstacle to innovation. They are not a benefit to the poor and hinder the transition. Low oil prices mean the timing for reform has never been better. It’s an urgent priority.”

In response, Christiana Figueres said that “we need to dispel the myth that you have to choose between burning carbon and development, the myth that with only this type of subsidy can you benefit the poor”. She also stressed that “we could be tempted to increase the subsidies to make up for losses…We need to decide which direction we are going. We could be locked in [to fossil fuel subsidies] for several decades. We must be guided by benefiting those at bottom of ladder.”

Responding to a question from Carbon Brief on what timescale the coalition would like see such “accelerated action”, John Key, the prime minister of New Zealand, said:

In the perfect world, as quickly as possible. Because, in the end, what is happening here is the world is spending close to half a billion dollars subsidising fuel which is not going to poor people. It’s money, actually, that governments could spend on so many other initiatives…One argument is to use that money to subsidise renewable energy, but even if you’re not prepared to do that, stopping subsidising something that is polluting the world is the best step you can take…I suspect for some countries it will be a phaseout [rather than immediately, as New Zealand did]. But this is the time to do it, as you do have low oil prices now so the elimination of those subsidies would have much less effect.

Rachel Kyte, the World Bank’s special envoy for climate change, added:

All of the economic evidences says that to delay costs you more. You run the risk of locking yourself into a high-carbon pathway that will be expensive.

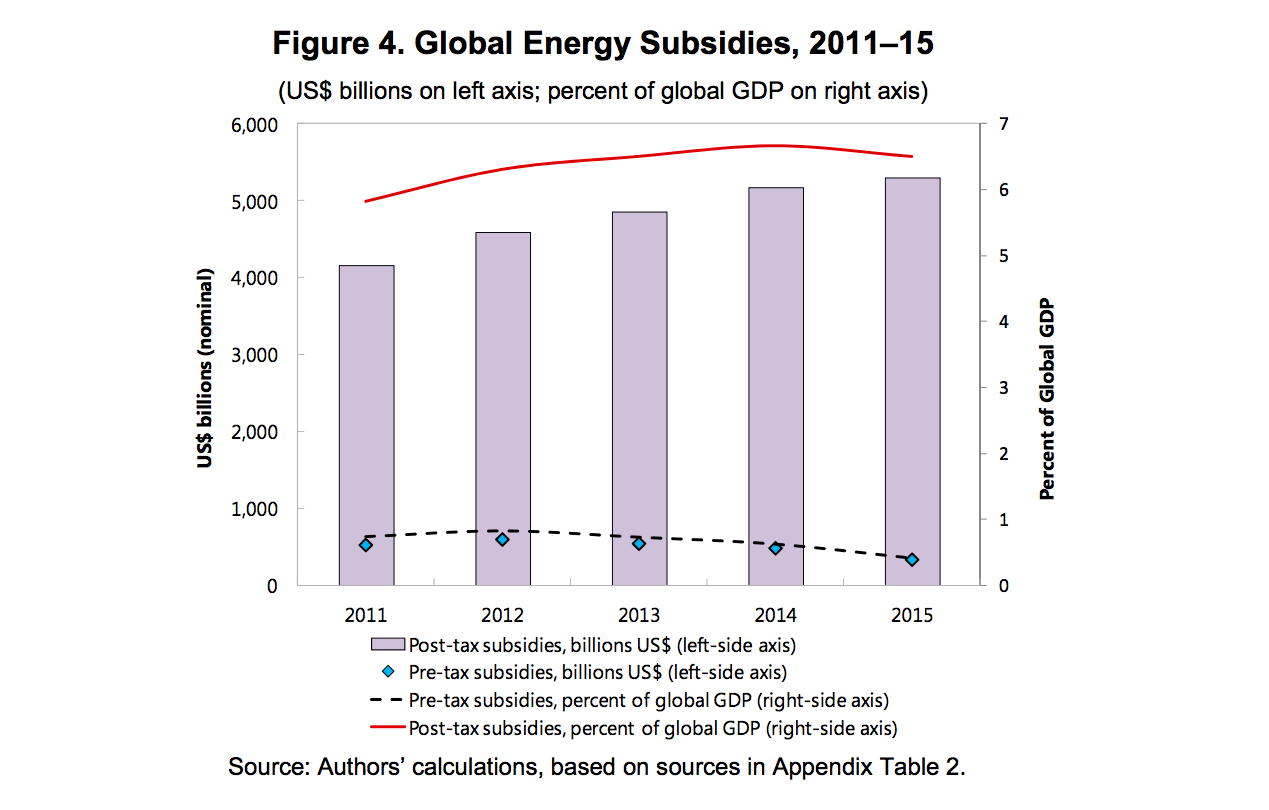

Earlier this year, a, International Monetary Fund working paper found that:

However, calculating fossil fuel subsidies is complicated and open to interpretation, as the IMF paper admits: “These findings must be viewed with caution. Most important, there are many uncertainties and controversies involved in measuring environmental damages in different countries – our estimates are based on plausible -but debatable -assumptions.”

The Climate Vulnerable Forum (CVF), a coalition of 20 countries from Afghanistan and Bangladesh to the Philippines, Rwanda and Vietnam, issued a declaration calling for the Paris agreement to include a 1.5C temperature limit.

The countries also want goals of 100% renewable energy and full decarbonisation by 2050, with peak emissions by 2020 at the latest. The Guardian said the declaration was significant because it broke ranks with the G77, which usually represents developing countries’ views.

A number of leaders used their speeches as an opportunity to announce new financial pledges. These include:

In addition, Germany, Norway and the United Kingdom pledged to contribute close to $300m to reduce deforestation in Colombia.

Ban Ki-moon announced a new initiative “to build climate resilience in the world’s most vulnerable countries”. He said the Climate Resilience Initiative (CRI) “will help address the needs of the nearly 634m people, or a tenth of the global population who live in at-risk coastal areas just a few meters above existing sea levels, as well as those living in areas at risk of droughts and floods”. The press release said:

Bringing together private sector organisations, governments, UN agencies, research institutions and other stakeholders to scale up transformative solutions, the SG’s Resilience Initiative will focus on the most vulnerable people and communities in Small Island Developing States, Least Developed Countries, and African countries. Over the next five years, the Initiative will mobilise financing and knowledge; create and operationalise partnerships at scale, help coordinate activities to help reach tangible results, catalyse research, and develop new tools.

The UN’s secretary general told the event that “we must absorb risks in new development models”. The event then heard from a series of leaders from countries most at risk from climate change, especially sea-level rise. Mark Rutte, the prime minister of the Netherlands, said that his country’s “battle against water had led to innovation and for us to prosper”. He then announced that the Netherlands will donate 50m euros to a new programme led by the Red Cross that will complement the CRI.

Meanwhile, a series of leaders from developing and vulnerable countries made the case for extra help. Freundel Stuart, the prime minister of Barbados, said: “We in the Caribbean and Pacific cannot adapt or build resilience to a 3C world.”

Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, Egypt’s president, said pointedly that “Africa is contributing least to global emissions, but it is the most vulnerable”. He added: “Developed countries not taking the lead exacerbates the problem. Egypt defends Africa’s interests on climate change.”

France said it would be initiating a new early warning system for vulnerable nations tomorrow and Germany said it would be helping to provide additional insurance for 200m people, although didn’t give more details.

Ban concluded by saying: “Most of our initiatives are coming from our hard lessons – politically and physically.”

The issue of vulnerability and resilience is a particularly emotive one within the climate talks and often becomes a bitter wedge between developed and developing nations. Ban Ki-moon’s efforts today can be seen as an early tactical effort by the UN to smooth edges and build bridges between parties ahead of the many days of negotiating that are still to come.

Emerging clean technologies received a boost, as investors and countries announced a new programme to help them pass through the “Valley of Death”, their poetic term for the gap between concept and viable product.

The group of 28 investors — which includes Microsoft’s Bill Gates, Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg and Amazon’s Jeff Bezos — have pledged to support early stage technologies, helping them to get off the ground at a time when other investors may be put off by the high risk factor involved. On their website, they outline the principles that will guide their investments.

In particular, the investors say they will focus on projects coming out of the 19 countries that have created the Mission Innovation coalition. This includes countries such as Canada, Germany, India, Japan, Saudi Arabia, the UK, the United Arab Emirates and the US. Each has pledged to double their governmental investment in clean energy technologies over the next five years.

Earlier this year, another group launched a “Global Apollo Programme to Combat Climate Change” with the aim of making clean energy cheaper than coal. It said the world should invest $15bn a year for a decade, though it lacked any clear funding commitments.

Switzerland, France, Germany, the US, the UK and others today made a joint pledge of $248m to the Least Developed Countries Fund, including $51m from the US and $53m from Germany.

The fund helps the world’s poorest nations draw up national adaptation plans to identify their climate vulnerabilities. It also funds urgent adaptation in sectors such as water and food security.

The fund has allocated nearly $1bn to projects since its inception in 2001, according to a joint statement published by the US State Department. This has unlocked $3.8bn of co-finance from other sources, the statement says.

The fund has sometimes struggled. A year ago, the BBC said hundreds of adaptation schemes might have to be abandoned for want of cash. Its coffers were empty this June,Reuters reported. The world’s 48 least developed nations will be hoping today’s pledge puts the fund back on track.

The World Bank, Germany, Norway, Sweden and Switzerland launched a new scheme to promote carbon pricing in developing countries. The Transformative Carbon Asset Facility (TCAF) aims to secure $500m in initial funding to “spur greater efforts to price and measure carbon pollution”.

Jim Yong Kim, the World Bank president, said the facility’s country partners “expect to commit more than $250m next year”. He said the $500m target, when reached, would leverage $2bn from the World Bank “and other sources”.

The TCAF will help create “the next generation of carbon credits”, says Kim in a statement. It is a complement to the Carbon Pricing Leadership Coalition, another World Bank initiative designed to increase the spread of efforts to tax or limit emissions through markets.

Fossil fuel subsidy reform, clean energy policy, carbon accounting, carbon pricing and carbon market initiatives could all benefit from TCAF support. The $500m funding target, if reached, would support 10 programmes, the World Bank says.

Posted by Guest Author on Monday, 7 December, 2015

|

The Skeptical Science website by Skeptical Science is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. |