This article goes into more depth, and has more quotes from my interviews with Professor Richard Zeebe and Professor Andy Ridgwell, than the original article I wrote for The Guardian, published January 29.

The Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM) was a global warming event with a relatively rapid onset that occurred 56 million years ago at the boundary between the Paleocene and Eocene geological epochs. Scientists have been studying the event because it is seen as an analog, albeit an imperfect one, of modern climate change.

With a global warming of 5º or 6ºC, it is the strongest warming episode to affect the planet in the time since the end-Cretaceous 66 million years ago (when the dinosaurs went extinct). Unlike the end-Cretaceous, the PETM was not a big extinction event but it generated enough environmental disruption to cause a high turnover of land animals, the evolution of ever smaller animals (the “Lilliput effect”), and a mass extinction of tiny shell-making creatures that live on the sea bed (benthic foraminifera).

The answer to that question has been an intractable problem for many years, but two new studies have independently just zeroed-in on the answer: 3 to 4 millennia.

More accurately, the two studies have constrained how long it took to release the initial carbon that drove global warming in the PETM – a crucial piece of information if we want to compare the PETM to today’s warming. The first study was presented in December at the AGU conference in San Francisco by Richard Zeebe and co-workers, who have calculated a duration of about 4,000 years or more. The second is a paper by Sandy Kirtland Turner and Andy Ridgwell in Earth and Planetary Science Letters, which was published online the same week, and which calculated that the carbon release took about 3,000 years or less.

Despite the difference, the fact that 2 independent studies, using different data and approaches, arrived at a very similar timescale is a huge advance on previous estimates that could do no better than say the onset of the PETM took somewhere between 5,000 and 20,000 years.

I had the opportunity to chat with both Richard Zeebe and Andy Ridgwell about the PETM at the AGU meeting in December.

Zeebe et al’s study was sparked by a controversial claim by Wright and Schaller in 2013 that the PETM may have been generated in as little as 13 years, possibly by a comet breaking up in the atmosphere. In a reply to that paper, Zeebe et al showed that it was impossible for the carbon release to generate a signal of ocean warming in such a short period of time.

"...would have to warm the entire planet by 5ºC within 13 years, which is impossible, unless the heat capacity of the ocean is zero, which we know is not the case!"

“The ocean has a heat capacity,” says Zeebe, “and so what happens is that after you release the carbon you get an increased greenhouse effect, the climate system picks up, and you get warming. It would not only have to release the carbon, but would have to warm the entire planet by 5ºC within 13 years, which is impossible, unless the heat capacity of the ocean is zero, which we know is not the case!”

But this also presented Zeebe with an opportunity. The Wright and Schaller study generated very detailed records of variations in the isotopes of carbon and oxygen through the PETM recorded by carbonates in clay sediments from New Jersey, USA.

“We strongly disagree with their interpretation, but we think that the data itself is useful to constrain the timescale of the PETM onset,” says Zeebe. “We have two isotope systems that we can look at. One of those are oxygen isotopes and they are essentially a thermometer, they tell us about climate change. And the other isotope system we’re looking at is carbon isotopes and they tell us something about carbon release.”

“We’ve accompanied these data with climate and carbon cycle modelling. So you take these data records and you try to model them, and you see immediately that if you run the carbon cycle and climate models there are serious problems if you assume the release was extremely fast [eg 13 years], because there’s a big delay between the carbon input signal and the climate response. So what we did with the model is: stretch the input of the carbon over longer and longer periods of time until we get a match between the observations and the carbon cycle and climate models. In that case we get a consistent story between what is physically possible in terms of the rate of heating of the climate system. As a result, we constrain that the onset of the PETM was probably in the order of 4,000 years.”

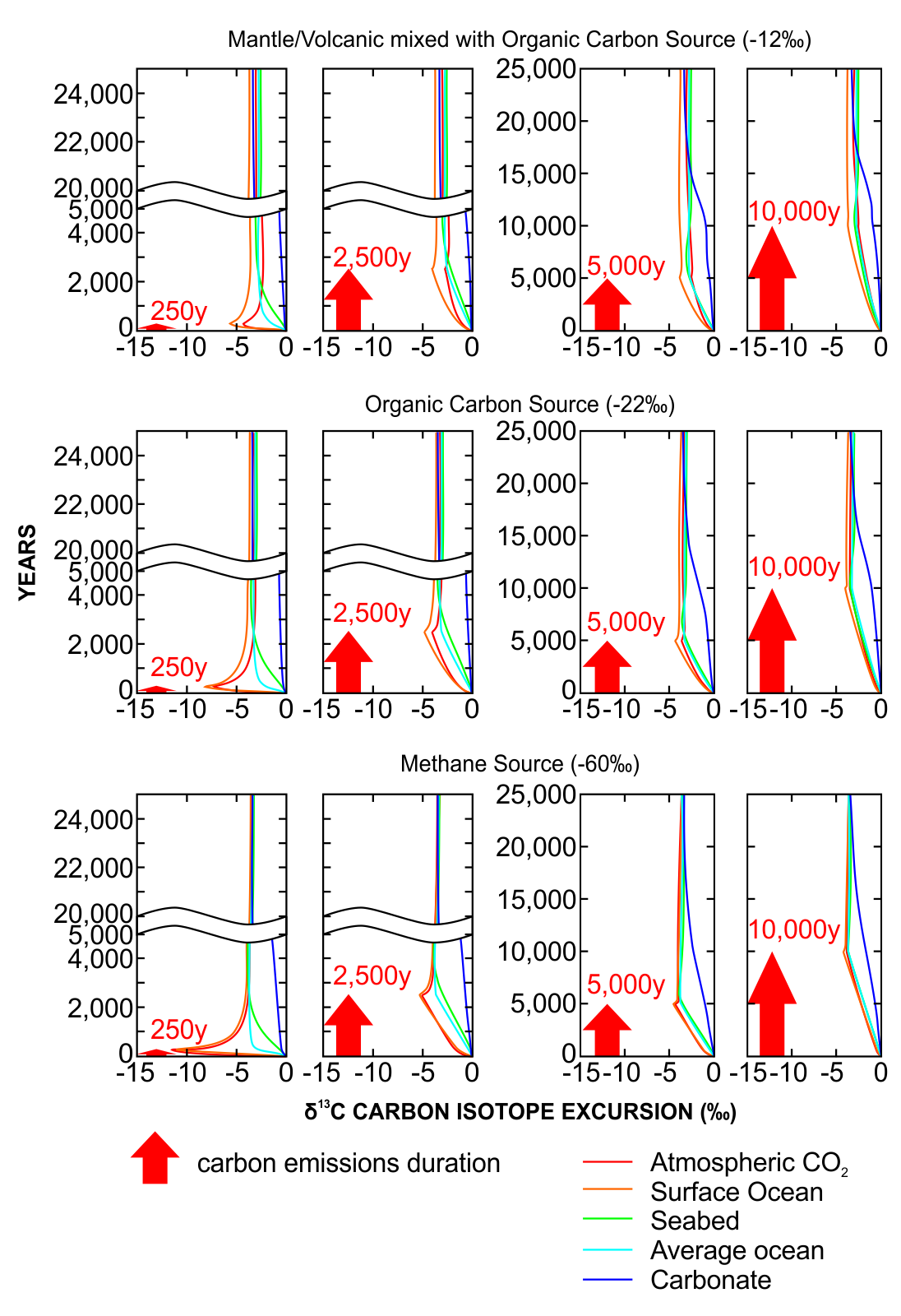

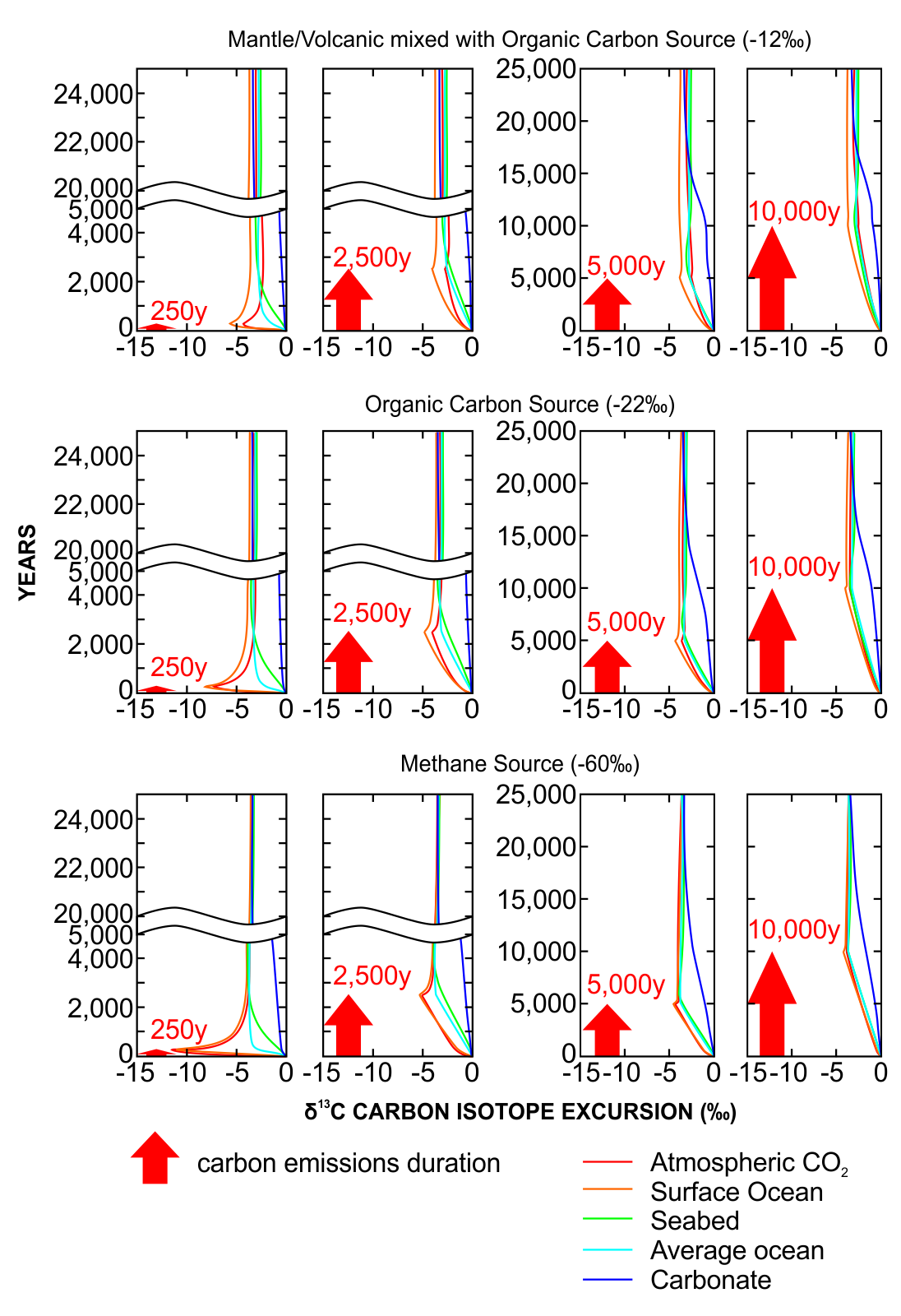

The approach taken by Sandy Kirtland Turner and Andy Ridgwell is different. They exploit the fact that the PETM carbon isotope curve recorded in land sediments is consistently larger that in marine sediments. This makes sense because it takes time to equilibrate an excess of CO2 in the atmosphere with the ocean, and the shallow ocean responds faster than intermediate or deep water, so the ratio of the land to marine signals is therefore proportional to the carbon emissions rate. They use a computer model to predict the size and shape of the isotope curves for a range of carbon emission sources and timeframes, and compare those with the actual isotope curves for the PETM recorded in various locations around the globe. Their best match provides an estimate of the onset of the PETM taking less than about 3,000 years.

Modeled carbon isotope curves (CIEs) for 3 different emissions sources over 4 different emission timeframes. Note the break in the timeframe in the left 2 columns. Redrawn and simplified from Kirtland Turner & Ridgwell, EPSL 2015, with annotations added.

The Kirtland Turner & Ridgwell method has found an empirical relationship between the average ocean carbon isotope excursion, the atmospheric CO2 level, and the duration of the carbon input that generated the climate change. This relationship, they argue, is generally applicable to other episodes of major carbon release in Earth’s past.

This is crucial because, even with recent advances in rock dating, the extreme warming events associated with the major mass extinctions in Earth’s past still seem to have very long durations compared to the ocean mixing time, which is about 1,000 years.

“A lot of these events like the end-Permian and the Triassic-Jurassic, when they’re linked to volcanism it does seem that these are relatively slow events overall, on timescales of tens to hundreds of thousands of years,” says Ridgwell. But that apparent slowness may be the result of a smeared sediment record of several shorter pulses of rapid emissions.

In their paper, Kirtland Turner and Ridgwell modeled the carbon isotope signal from 10 short emission pulses spread over 1,000 years and compared that with the signal from the same overall carbon release spread evenly over 1,000 years. The results in the average ocean, seabed, and sedimentary carbonate records were identical between the pulsed and continuous scenarios, showing that those records are incapable of resolving a series of very short pulses.

"...could individual pulses look anything like what we’re doing now in terms of amount and rate? That’s an area of active research..."

“Even the PETM we’re thinking that it’s possible it wasn’t just several thousand years of continuous CO2 release, but it could have been a bunch of very short pulses. Many records tend to smear-out the signal so something that is actually a series of very, very, short and rapid pulses could actually look like a long continuous release of CO2, and therefore, could individual pulses look anything like what we’re doing now in terms of amount and rate? That’s an area of active research because the estimates of individual pulses are getting better, but the estimates of how much CO2 would be released associated with an individual pulse is still of the order-of-magnitude uncertainty, which is not helpful to really talk about emission rates.”

With two independent studies triangulating the onset of the PETM in the 3,000-4,000-year timeframe, it puts modern climate change into perspective.

“What we’re doing with our emissions is unprecedented in the past 66 million years!” says Zeebe.

Zeebe et al (2015) point out that our current climate change, occurring in just a couple of centuries, has no analog in the past 66 million years, which presents a challenge for our ability to predict the long term consequences of modern climate change. They go on to say that “future ecosystem disruptions will likely exceed the relatively limited extinctions observed” at the PETM.

But even if the PETM isn’t a perfect equivalent of today’s climate (it was slower, and it happened in a world that was already warmer than today), it still provides useful lessons on how the planet reacts to a geologically rapid release of carbon into the atmosphere.

For example, the 2013 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report says we can expect a warming of between 1.5ºC and 4.5ºC if we double atmospheric CO2 levels, but also acknowledges that the long term warming “could be significantly higher” than that. The PETM tells us the long-term sensitivity (“Earth System Sensitivity”) must be higher.

"...most mass extinctions were CO2-driven global warming things"

“If we just try to explain the PETM with a climate sensitivity of 4.5ºC, we only get maybe 60% of the warming. So my conclusion would be that long term sensitivity must be more than 4.5ºC,” says Zeebe.

“Apart from the stupid space rock hitting the Earth, most mass extinctions were CO2-driven global warming things,” says Ridgwell. “If you screw with the climate enough, you have huge extinctions. The difficulty is how much is enough, and what goes extinct. And then it comes down to rates, and their complications.”

Posted by howardlee on Thursday, 11 February, 2016

|

The Skeptical Science website by Skeptical Science is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. |