On December 12, the 21st annual meeting of the world’s climate negotiators closed with adoption of the Paris Agreement. The task agreed by consensus among 195 nations is clear, ambitious, and complex: re-engineer the infrastructure of the global economy to eliminate practices that destabilize Earth’s climate system, while ensuring ongoing and expanded prosperity for all people everywhere.

That the task is difficult should not put us back on our heels. As we move into new territory, we will face new obstacles. This is how we learn, how we know if we are up to the challenge, how we know which adjustments to make, and how we succeed in crossing an unknown ocean.

For centuries, explorers have sought to navigate the Northwest Passage—a shortcut from Europe to Asia that wouldn’t require sailing around the southern extremes of Africa or South America. For much of that time, the idea was something between a flight of fancy and a dangerously unapproachable challenge. Many have died making the attempt.

Twenty-one years ago, in the summer of 1994, a 57-foot fiberglass sailboat named Cloud Nine set sail, with captain Roger Swanson at the helm. Cloud Nine carried a crew of six, who were attempting to transit the fabled Northwest Passage from east to west. There was a tremendous amount of pack ice choking off all the routes through the Passage that summer, and the crew of Cloud Nine was forced to abandon the voyage and retreat out of the Arctic.

In Barrow Strait, near the Canadian village of Resolute, Cloud Nine encountered dense pack ice that could trap and sink even a larger vessel. The crew were forced to turn back to ensure their survival. Photograph: David Thoreson

Thirteen years later, in the summer of 2007, Cloud Nine returned to the Arctic for another east-to-west attempt. This time around, the crew of six discovered little to no ice in the Northwest Passage. To the astonishment of those on board and of those watching their transit, the nearly 7000-mile voyage took only 73 days, and Cloud Nine never touched one piece of ice.

Shot at the same place as the above photo from the 1994 expedition, this 2007 photo clearly shows open water where there should be close and dangerous pack ice. Photograph: David Thoreson

The Passage was wide open and completely ice-free. Cloud Nine was the first American vessel in history to complete the east-west transit of the Northwest Passage. Members of the crew acknowledged they got an assist from a changing Arctic, characterized by far less ice.

The reliable deep cold of the polar regions is part of what gives us a stable climate system: with extreme cold at the poles, the warmer climate bands of lower latitudes are more stable and defined. That defined differentiation of climate bands keeps the Polar Vortex swirling in the Arctic. Cold reinforces cold, which keeps the climate bands steady. As the Arctic warms, the warmer air mixes more readily with the climate of lower latitudes, and the Polar Vortex “bleeds” into those other latitudes, bringing deep Arctic winter to more temperate regions.

This is climate destabilization.

Captain Roger Swanson navigates, without the benefit of satellite navigation. Photograph: David Thoreson

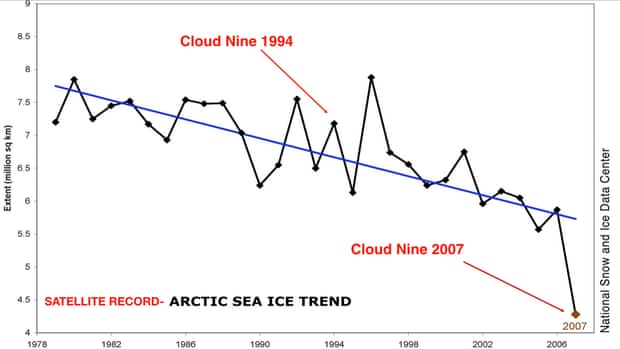

When Cloud Nine first ventured into the Arctic in 1994, there was limited computer and GPS technology and no satellite communication. By the time the pioneering vessel returned to the Arctic in 2007, however, the technology had changed. Through the Internet, it has become possible to study records of the Arctic’s ice extent, using photos and data mapping from satellites launched in the late 1970s. A clear downward trend was beginning to emerge by 2007.

NASA’s Earth-observing satellites monitor polar ice cover, among other vital signs. In summer 2007, when Cloud Nine transited the Northwest Passage, NASA satellites showed the Passage entirely free of ice. Photograph: NASA

In the 13 short years between those two sailing expeditions to the far north, there had been a forty-percent loss of summer sea ice in the Arctic Ocean. That is a 40% loss of our North Polar ice cap. This change is happening outside of Earth’s natural and geological cycles. Human activity is having a profound and sudden impact on our planetary climate systems and the Arctic is experiencing the most rapid and visible change.

A look at annual ice cover readings shows a steady decline in Arctic Ocean ice, down 40% by 2007. Illustration: David Thoreson, NSIDC

We stand at the dawn of a new age of exploration. We have sailed the oceans and photographed the Earth from space. Now, we see entire regions changing so quickly, our exploration of the physical world is becoming an exploration of how Earth’s life-support systems work, where they are vulnerable, and what our choices have to do with it.

Our civilization has been designed by human beings. The design we have inherited is generating this unprecedented global challenge. How we respond requires people to work together politically.

Six heads of state join the heads of the World Bank and OECD to advocate for smart carbon pricing, on the first day of the COP21. Photograph: Joseph Robertson

The halls of power often resemble the Arctic—a sparsely populated remote vastness full of peril, where success is almost out of the question. It requires real moral courage to stand up and to do the work of an engaged citizen.

While staying on familiar shores is comfortable, the political challenge of getting all of this right means all of us are called to venture out. Some of us go and speak to our lawmakers. Others must build new civic spaces for shared decision-making. Even in nations transitioning from conflict to a new civil state, individuals can steer events by their presence, by giving voice to their conscience, by learning from others, and by staying engaged over time.

Joseph Robertson is Global Strategy Director for the nonpartisan nonprofit organization Citizens’ Climate Lobby.

David Thoreson is a documentary photographer and the first American to sail the Northwest Passage in both directions.

Posted by Guest Author on Friday, 12 February, 2016

|

The Skeptical Science website by Skeptical Science is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. |