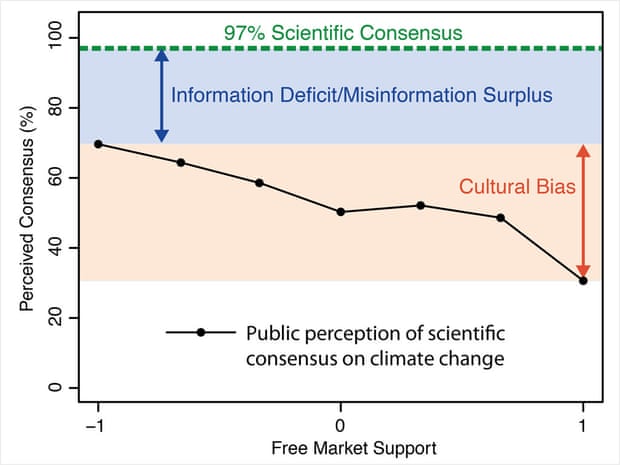

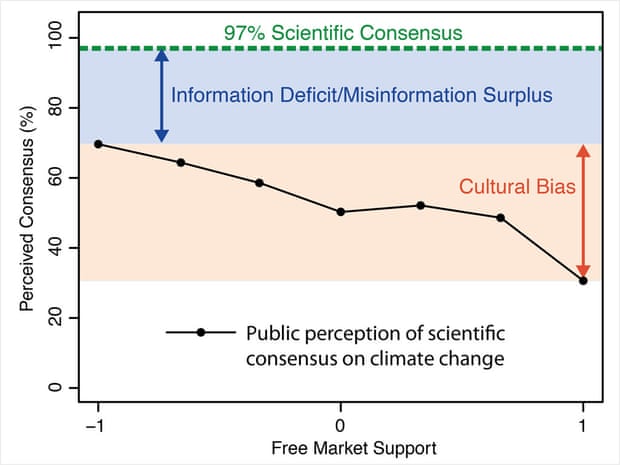

Perceived expert climate consensus across the political spectrum from a nationally representative sample of 200 Americans. Even liberals significantly underestimate the expert consensus on human-caused global warming. Illustration: John Cook

Perceived expert climate consensus across the political spectrum from a nationally representative sample of 200 Americans. Even liberals significantly underestimate the expert consensus on human-caused global warming. Illustration: John CookJohn Cook is a research assistant professor at the Center for Climate Change Communication at George Mason University, researching cognitive science.

Sander van der Linden is an Assistant Professor in Social Psychology, Director of the Cambridge Social Decision-Making Lab and a Fellow of Churchill College.

Anthony Leiserowitz is a Research Scientist and Director of the Yale Project on Climate Change at the School of Forestry and Environmental Studies at Yale University.

Edward Maibach is a University Professor and Director of Mason’s Center for Climate Change Communication.

Unfortunately, humans don’t have infinite brain capacity, so no one can become an expert on every subject. But people have found ways to overcome our individual limitations through social intelligence, for example by developing and paying special attention to the consensus of experts. Modern societies have developed entire institutions to distill and communicate expert consensus, ranging from national academies of science to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Assessments of scientific consensus help us tap the collective wisdom of a crowd of experts. In short, people value expert consensus as a guide to help them navigate an increasingly complex and risk-filled world.

More generally, consensus is an important process in society. Human cooperation, from small groups to entire nations, requires some degree of consensus, for example on shared goals and the best means to achieve those goals. Indeed, some biologists have argued that “human societies are unable to function without consensus.” Neurological evidence even suggests that when people learn that they are in agreement with experts, reward signals are produced in the brain. Importantly, establishing consensus in one domain (e.g. climate science) can serve as a stepping stone to establishing consensus in other domains (e.g. need for climate policy).

The value of consensus is well understood by the opponents of climate action, like the fossil fuel industry. In the early 1990s, despite the fact that an international scientific consensus was already forming, the fossil fuel industry invested in misinformation campaigns to confuse the public about the level of scientific agreement that human-caused global warming is happening. As has been well-documented, fossil fuel companies learned this strategy from the tobacco industry, which invested enormous sums in marketing and public relations campaigns to sow doubt in the public mind about the causal link between smoking and lung cancer.

However, some academics have recently argued that communicators and educators should not inform the public about the strong scientific consensus on climate change. UK sociologist Warren Pearce and his colleagues recently published a commentary (and corresponding Guardian op-ed) arguing that communicating the scientific consensus is actually counter-productive. John Cook published a reply, which we summarize here.

By the late 1990s, political strategists recognized the importance of perceived scientific consensus. Market researcher Frank Luntz advised Republicans and then-president George W. Bush to cast doubt on expert agreement in order to reduce public support for climate policy. To stall climate policy, he argued, the Bush Administration should seek to convince the public that scientists were still arguing whether climate change is real or human-caused.

Evidence Squared podcast on why denialists attack consensus.

Luntz was ahead of his time. It was over a decade before social scientists began studying this phenomenon and converged on the same result. A 2011 studyfound that support for climate policy was linked to perceptions about scientific agreement on climate change. This finding has since been independently replicated by other research, as well as randomized experiments conducted in Australia and the United States. Still other research confirmed these results using John Oliver’s viral TV segment illustrating the issue of “false balance” to the public.

Conversely, telling people that experts disagree was found to decrease their support for environmental policy and other actions, such as vaccinations.

To push back against the decades-long disinformation campaign, numerous scientists have made efforts to quantify and communicate the scientific consensus. Meanwhile, disinformers have doubled down on their efforts to confuse the public about the consensus. The commentary by Pearce and company plays into their hands by arguing the climate community should surrender this argument to the misinformers.

In the Guardian, Pearce argued:

the public have already heard enough about the scientific evidence to make up their mind, without being fed increasingly esoteric information about levels of scientific agreement … valuable media and political attention has been expended on boosting the 97% meme, crowding out deeper conversations about policy framing

However, in the United States, only 70% of Americans understand that global warming is happening, and only 58% understand it is human-caused. Further,only 13% of Americans realize the expert consensus on human-caused global warming exceeds 90%.

Perceived expert climate consensus across the political spectrum from a nationally representative sample of 200 Americans. Even liberals significantly underestimate the expert consensus on human-caused global warming. Illustration: John Cook

Perceived expert climate consensus across the political spectrum from a nationally representative sample of 200 Americans. Even liberals significantly underestimate the expert consensus on human-caused global warming. Illustration: John CookAnd multiple empirical studies, conducted in different countries, have found that informing people of the scientific consensus has a small but significant influence on their own subsequent judgements about the reality of human-caused global warming. While discussion about climate policy is urgently needed, establishing and communicating the scientific consensus about human-caused climate change is not a competitor to policy discussion; it is a complement.

No one argues that the scientific consensus is the one and only message that needs to be communicated - public responses to climate change are often as complex as society itself. But informing the public about the scientific consensus that the problem actually exists can support the discussion on how to best solve the problem. The argument that we have to choose between debunking the climate policy opponent’s disinformation about the scientific consensus or engage in meaningful policy dialogue is a false choice.

Disinformation about the scientific consensus that human-caused climate change is happening has been used to delay serious conversations about climate policy in the United States and a few other countries. Moreover, the argument that communicators should not talk about a scientific consensus when one exists is deeply troubling. In the history of science, it is relatively rare that such strong agreement emerges about basic scientific facts. When it comes to issues such as the future of our planet, recommending that we withhold this information from the public is unethical.

American policymakers have struggled to implement national climate policies, but not for lack of policy discussion “crowded out” by consensus messaging.

Posted by dana1981 on Monday, 2 October, 2017

|

The Skeptical Science website by Skeptical Science is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. |