Global warming means truly global warming. The atmosphere, the oceans, and the ground are all warming. As a result, ice is melting, seas are rising, storms are getting more severe, and droughts are getting worse. But these things are not happening in isolation. The tricky thing about the climate is that things are connected all across the globe. And those connections are revealing changes that may not be obvious at first glance.

One such change was exposed in a recent paper published in the journal Environmental Research Letters by a team of top scientists from China and Brazil, an instructive video is available here. The scientists focused their study on the Amazon rainforest. There, the year is broken into “wet” and “dry” seasons. The researchers wanted to know how rainfall has changed during the wet seasons over the past few decades.

What they found was astonishing – the rain in this tropical rainforest has increased 180–600 mm (7–24 inches). They learned about the increase in wet-season rainfall by reviewing old weather data – information from rain gauges for example. They also used satellite measurements to complement the rain gauge readings. The trend they found was clear – the rains are increasing.

So, any good scientist wants to know why. Why are the rains increasing? What is the main cause? By using the results of state-of-the-art climate calculations, the authors showed that the temperatures in the Atlantic Ocean are primarily responsible. The Pacific Ocean water temperature plays a smaller role.

This study is really important for a few reasons. First, the Amazon is important for the entire globe’s climate. The rainforest provides about 20% of the Earth’s freshwater. There is a tremendous amount of evaporation from the rainforest into the air. This evaporated water is carried to other parts of the planet where it falls as rain. We call the evaporation/precipitation process a “hydrologic cycle.” This cycle refers to the movement of water throughout the planet; the Amazon is an important engine for the cycle.

But the importance of the Amazon is broader than just water. The growth and decay of wood and plant growth there means the Amazon absorbs and emits large amounts of carbon dioxide. Think of the rainforest like the lungs of the planet. They help the planet breathe.

The Amazon rainforest also helps transfer heat throughout the Earth’s climate. Energy moves from one location to another with help of processes (such as evaporation and condensation) that originate in the Amazon. In these ways, the Amazon connects far-flung parts of the planet together. What happens in one region like the Pacific Ocean affects the climate elsewhere like the Atlantic Ocean. The way the climate interacts between to distant locations is called “teleconnections.” And the Amazon is a great teleconnector for the planet.

Previous researchers who have looked at the Amazon and its changing precipitation have found that the southern part of the rainforest has experienced a long-term increase in rainfall. Researchers have also found changes to the monsoon cycles that affect the rainforest. But with most of these studies looking at the southern Amazon, very little was known about the northern region. What was happening there? Also, most of the early studies looked at changes to rain during the dry season. The authors of this new study wanted to focus on the wet seasons.

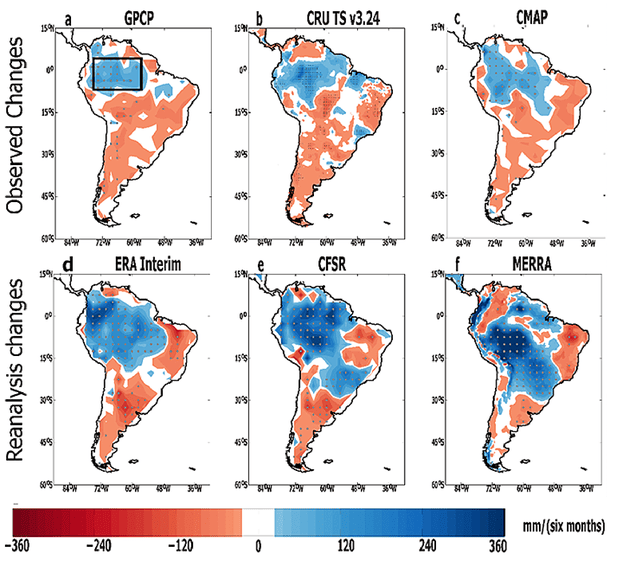

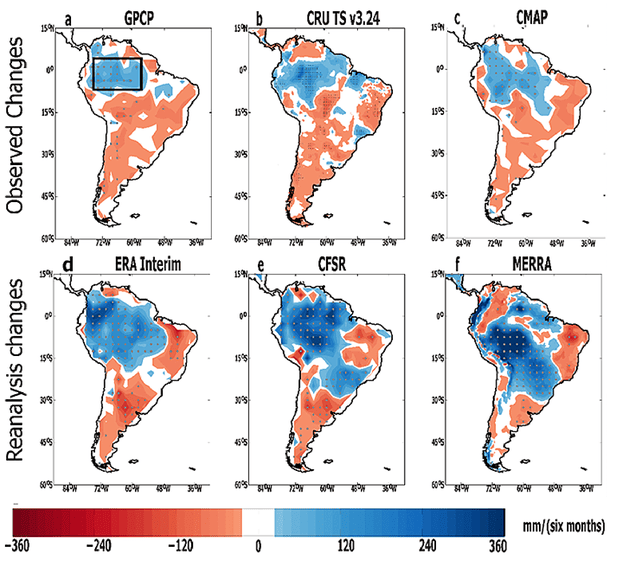

The authors used six different methods to look at the data. Three methods were based on actual rainfall measurements. Three additional methods were based on a technique called climate reanalysis – essentially combining measurements and climate calculations. The image below, which is from the paper, shows results for the six methods. The blue regions indicate places where the rainfall is increasing. Areas in orange/red correspond to decreasing rainfall. The results correspond to December through May and the trends are based on 1979–2015.

December through May averaged precipitation change from 1979 to 2015 in observation and reanalysis over South America. Illustration: Wang et al. (2018), Environmental Research Letters

The general results are the same, regardless of which of the six methods are used. In particular, in the black box (upper left image), the six methods give very similar results. It doesn’t matter whose inputs are used; the rainfall there is increasing.

Posted by John Abraham on Wednesday, 12 September, 2018

|

The Skeptical Science website by Skeptical Science is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. |