Ynyslas, on the Cardigan Bay coast of Wales, is a place well-known for its extensive, shingle spit-fronted sand-dunes, its hinterland of estuarine saltmarsh-flats and, seaward, its golden sandy beach, complete with a several thousand year-old submerged forest. The place gets some 250,000 visitors a year. Taking all of those factors into account, and that Ynyslas is also a direct product of actual climatic changes that occurred in the geologically-recent past, its tale was ripe for the telling, so that's just what I did. I wrote a book about it.

The Making of Ynyslas is a climate science book with a difference. It is an account of how climate change brought one well-loved modern landscape into existence, but in doing so, destroyed another. Covering the last 25,000 years, since around the time of the Last Glacial Maximum, the story involves the details of deglaciation as the world's great ice-caps retreated polewards and seas rose, sometimes gradually and sometimes rapidly, by some 125 metres. In doing so, large areas of land were drowned: on a human time-scale, the changes would be permanent. On a geological time-scale, over hundreds of millions of years, the area now occupied by Cardigan Bay has variously been dry land or underwater on several occasions. In addition to climate change we have to consider the area's tectonic evolution over such lengthy time-frames, which are outside of the scope of the book, covering as it does the latest Pleistocene and the Holocene Stages of geological time.

Lumped together, these two stages make up the latter part of the Quaternary System, which began, following the Pliocene, 2.58 million years ago. The Quaternary represents a diversion away from the norm of the previous tens of millions of years, in that it featured regular and cyclic advances of ice-sheets, equatorwards from the Polar regions. For long stretches of geological time prior to the mid-Cenozoic, say from before some 35 million years ago, Polar ice was not a regular feature on the menu at all. So the changes from that climate state to the alternating glacials and interglacials of the Quaternary were, by definition, profound. But in order to understand how such changes came about, it is first necessary to look at past times when Earth has had an Icehouse climate. It's not a particularly common climate state over geological time and perturbations to the Slow Carbon Cycle have had a hand in every such switch.

Such changes have included the development of photosynthetic plantlife and the oxygenation of the atmosphere, at the expense of the methane that had once been common, in the early Proterozoic. Large eruptions of flood-basalt or the creation of new mountain-chains, at various times, have initiated enhanced weathering regimes. The greening of Earth's land-surface, from the first miniature and primitive land-plants in the Ordovician, to the luxuriant forests that had become widespread by the Carboniferous, again increased photosynthetic activity. All of these phenomena had one thing in common: they led to significant CO2 draw-down and a reduction in the overall greenhouse effect, thereby favouring cooler conditions.

Of course, without us around to burn the fossil fuels, other sources of greenhouse gases were required to balance things in the other direction. Chief among these was volcanic activity. Sometimes, it may have been a slow but steady build-up of volcanogenic CO2; such was probably the case at the end of “Snowball Earth” episodes, when many CO2 draw-down routes were either not available or severely limited in their scope. If you cover most of Earth in ice-sheets, weathering becomes minimal; atmosphere-ocean gas exchange is mostly blocked and photosynthetic algae and cyanobacteria find a lot fewer available niches to occupy. But volcanism is driven by much greater forces – movements within Earth's mantle and plate tectonics. It doesn't matter too much whether Earth has ice-sheets or not: for volcanoes it's business-as-usual. At other times, Earth has suffered shocks due to volcanism on an unimaginable scale, in which global warming and pollution were evidently involved. We covered the end-Permian mass-extinction and its demonstrable link to the catastrophic Siberian Traps volcanism in 2015, here and here.

Once the Slow Carbon Cycle has helped force a cool-down, other factors become important, too. The multi-thousand year Milankovitch Cycles affect the nature of Earth's orbit around the Sun and also the planet's own tilt on its axis: in an Icehouse climate, such things can affect seasonal sunlight input, to the extent that they permit advances and retreats of ice-sheets over long periods. Climate feedbacks are also important: for example, fresh snow covering sea-ice reflects 90% of incoming sunshine, but remove that ice, by whatever cause, and the open sea-water instead absorbs 94% of the solar energy.

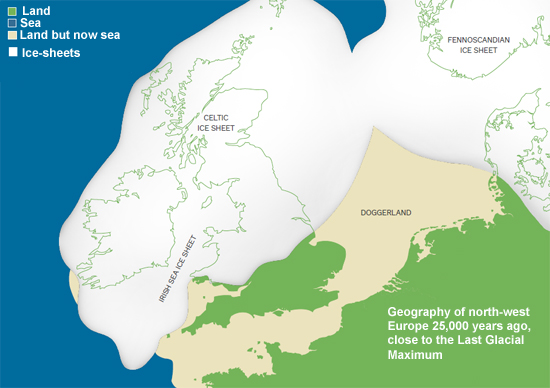

Above - approximate extent of ice-sheets close to the Last Glacial Maximum: redrawn after consulting multiple literature sources e.g. Shennan et al. 2018. Annotation partially redone to adapt to image size limits.

Having looked at such things in detail, the scene is now set for the narrative itself. This is a tale involving a certain amount of Quaternary geology but also the nature of the beast that is sea level rise. We tend to think of the latter as a thing of the future, even though right now, spring tides are a cause for concern in many parts of the world, such as the Florida coast. A hundred and twenty-five metres of sea level rise is an awful lot. If our current fossil fuel-burning activities continue unabated, leading eventually to the melting of all ice on Earth, the seas would rise by "only" some 70 metres.

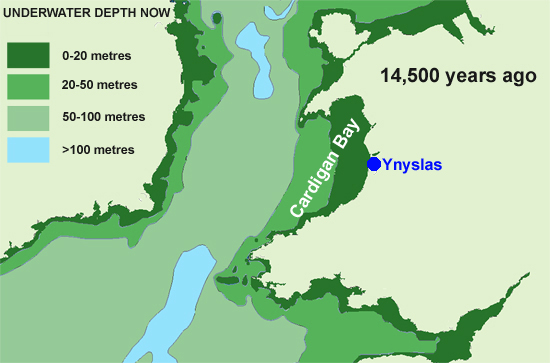

At the Last Glacial Maximum, a vast glacier occupied what is now the Irish Sea, reaching down beyond the Isles of Scilly towards the edge of the continental shelf. Yet its retreat was remarkably fast and it left in its wake an ecological blank slate, ripe for colonisation, for the great ice-caps of Scandinavia and America remained. Ice-caps have a lot of inertia when it comes to melting them. Because Cardigan Bay is so shallow – all of it is less than fifty metres deep – there was a considerable time when it remained ice-free yet land. Drill-cores extracted from boreholes out in the Bay have encountered, in various depths of water and at various depths beneath the sea-floor, beds of peat representing bygone forests that thrived at various points along this time-line. It was not until around 12,000 years ago that the seas began to invade this wooded plain and it took another six thousand years to bring the sea close to the modern coastline. The famous submerged forest on Borth-Ynyslas Beach, visible on low tides, is even more recent. The flooding thereby spans the period of time from the latest Palaeolithic through to the Neolithic: people were almost certainly present to witness the intergenerational drowning of what would have been fertile hunting-country, akin to the Doggerland of the North Sea.

Above - sketch-map of the Irish Sea, redrawn from nautical charts. The time represented here is close to the start of Meltwater Pulse 1A, a remarkably rapid phase of sea level rise over a number of centuries. However, at its start, sea levels were still some 100 metres lower than at present, so that Cardigan Bay would have been land, and would remain so for some considerable time to come.

Interestingly, among the various Flood Legends that appear to have originated independently all around the world, Cardigan Bay has its own version. Cantre'r Gwaelod – the Lowland Hundred, was an ancient kingdom in what is now the Bay, complete with a settlement protected by sea-defences and sluice-gates. By various mechanisms (there are several versions), the gates were neglected on a night of storm and the sea poured in, ruining the place.

I've long been intrigued by these flood-legends, arising in widely separate places (in terms of both physical distance and culture). Are they fragmentary memories of an eustatic sea level rise that continued relentlessly for generations, handed down via the oral tradition? It's interesting to speculate even when admittedly the evidence is likewise fragmented.

Above: the author at Borth beach, examining part of the Submerged Forest as the tide ebbs. Photo: Doug Bostrom.

More definite, though, is the fate awaiting the coasts of the world if we carry on recklessly burning the fossil fuels. The book finishes on this note because it is necessary to do so. Is Cantre'r Gwaelod 2.0 possible? The laws of physics say yes – and in this case the cause of the flooding will definitely be ourselves – if we do not act to change the way in which we live. Yet we are capable, given the correct tools, of diverting away from this destructive path, so the book ends on the hopeful note that this is indeed an option for us.

The Making of Ynyslas, the initial draft of which was helpfully reviewed by several fellow SkS team-members, is available from Coch-y-Bonddu Books, Machynlleth and via their website, cost £7.50 plus p&p:

https://www.anglebooks.com/the-making-of-ynyslas--tales-from-an-area-the-size-of-wales---25000-years-ago-to-the-present-day-by-john-s-mason.html

All around the world, there are places whose physical features directly reflect the changes brought about by deglaciation and eustatic sea level rise. Why not write about them? Tell us the story of your own back-yard and how drastically it was altered by climate change. Climate change can occur for various reasons although our reckless fossil fuel-burning has a certain uniqueness to it. But whatever the cause and however long the time-line, the effects are nevertheless profound and make the tale well worthy of the telling. Such accounts may, in turn, help people to finally understand what this is all about and why, while they go about their daily lives, others are striking from school or demonstrating in the world's capital cities in order to get the message across.

Reference:

Shennan, I., Bradley, S.L. and Edwards, R., 2018. Relative sea level changes and crustal movements in Britain and Ireland since the Last Glacial Maximum. Quaternary Science Reviews, 188, pp.143-159.

Posted by John Mason on Thursday, 31 October, 2019

|

The Skeptical Science website by Skeptical Science is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. |