Thinking is Power: The problem with “doing your own research”

This is a re-post from the Thinking is Power website maintained by Melanie Trecek-King where she regularly writes about many aspects of critical thinking in an effort to provide accessible and engaging critical thinking information to the general public.

This is a re-post from the Thinking is Power website maintained by Melanie Trecek-King where she regularly writes about many aspects of critical thinking in an effort to provide accessible and engaging critical thinking information to the general public.

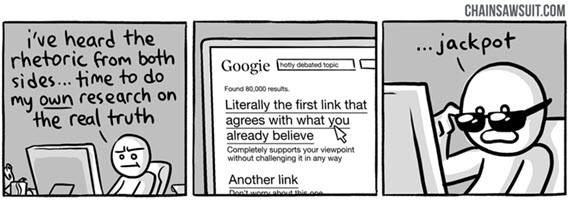

The phrase “do your own research” seems ubiquitous these days, often by those who don’t accept “mainstream” science (or news), conspiracy theorists, and many who fashion themselves as independent thinkers. On its face it seems legit. What can be wrong with wanting to seek out information and make up your own mind?

Image Credit: Thinkingispower.com

The problems with “doing your own research”

1. That’s not what research is.

Definitions matter. When scientists use the word “research,” they mean a systematic process of investigation. Evidence is collected and evaluated in an unbiased, objective manner, and those methods have to be available to other scientists for replication.

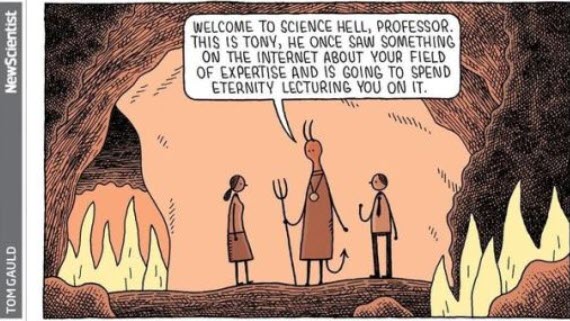

Conversely, when someone says they’re “doing their own research,” they mean using a search engine to find information that confirms what they already think is true. We are all prone to confirmation bias, and the effect is especially powerful when we want (or don’t want) to accept a conclusion.

Science as a process is an attempt to understand reality, and recognizes how biased and flawed the human brain is. That’s why real research is about trying to prove yourself wrong, not right.

Image Credit: Chainsawsuit.com

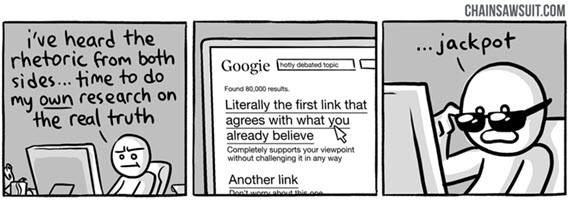

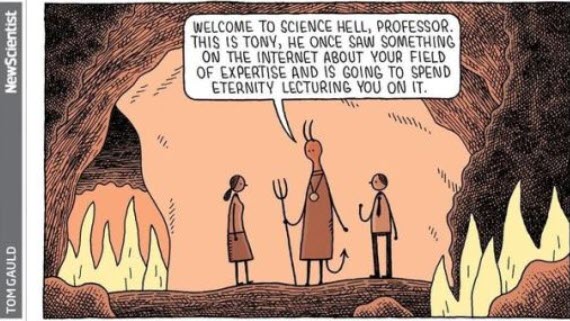

2. You’re not as smart as you think you are.

Unless you’re an expert in the field you’re “researching,” you’re almost certainly not able to fully understand the nuance and complexity of the topic. Experts have advanced degrees, published research, and years of experience in their sub-field. They know the body of evidence and the methodologies the researchers use. And importantly, they are aware of what they don’t know.

Can experts be wrong? Sure. But they’re MUCH less likely to be wrong than a non-expert.

Thinking one can “do their research” on scientific topics, such as climate change or mRNA vaccines, is to fool oneself. It’s an exercise in the Dunning-Kruger effect: you’ll be overconfident but wrong.

Yes, information is widely available. But it doesn’t mean you have the background knowledge to understand it. So know your limits

Image Credit: Tom Gauld at New Scientist

The process of science is messy

Science is messy. For example, climate change research involves experts from a variety of fields (e.g. earth sciences, life sciences, physical sciences) and settings (e.g. academia/government/industry), from nearly every country on earth, each looking at the issue using different methods. Their findings have to pass peer review, where other experts evaluate their work before it can be published.

The literature is also messy, as different studies provide different types and qualities of evidence. Different studies also might reach slightly different conclusions, especially if they use different methodologies. Findings that are replicated have stronger validity. And when the various lines of research converge on a conclusion, we can be more confident that the conclusion is trustworthy.

And then there’s the news, which tends to report on new, unique, or sensational findings, generally without the detail and nuance in the literature.

All of this messiness can leave the public thinking that scientists “don’t know anything” and are “always changing their minds.” Or that you can believe whatever you want, as there’s “science” or a “study” or even an “expert” that supports what they want to be true.

Waiting for proof

Most people seem to understand that science is trustworthy. After all, we can thank science and resulting technology for our modern quality of life. Unfortunately, there’s much the public doesn’t understand about science, including the enduring myth that science proves.

Scientific explanations are never proven. Instead, science is a process of reducing uncertainty. Scientists set out to disprove their explanations, and when they can’t, they accept them. Other scientists try to prove them wrong, too. (And scientists LOVE to disagree. Anyone who thinks scientists are able to conspire has never had a conversation with one.) The best way for a scientist to make a name for themselves is to discover something unknown or disprove a longstanding conclusion.

The process of systematic disconfirmation is designed to root out confirmation bias. Those insisting on “scientific proof” before accepting well-established science are either misled or willfully using a fundamental characteristic of science to avoid accepting the science.

Why we should trust science and the experts

Back to “researching.” The danger is that uninformed or dishonest people can cherry pick individual studies, or even an expert, to support a particular conclusion or to make it look like the science is more uncertain than it is…especially if they don’t want to accept it. And if we’re being real, many who “do their own research” are doing so to deny scientific knowledge. But that’s the perfect storm for being misled, and for many scientific issues the price of being wrong is just too high.

Ultimately knowledge is a community effort. We don’t think alone…. and that’s what makes humans a successful species. The problem is that we fail to recognize where our knowledge ends and the community’s begins. That’s why for anyone who isn’t an expert in a particular field, our best chance at knowledge is to trust what the majority of experts in that area say is true. No “research” involved.

To learn more

Forbes: You must not ‘do your own research’ when it comes to science

Thinking Is Power: Don’t be fooled…Fact Check!

Posted by Guest Author on Tuesday, 3 August, 2021

This is a re-post from the Thinking is Power website maintained by Melanie Trecek-King where she regularly writes about many aspects of critical thinking in an effort to provide accessible and engaging critical thinking information to the general public.

This is a re-post from the Thinking is Power website maintained by Melanie Trecek-King where she regularly writes about many aspects of critical thinking in an effort to provide accessible and engaging critical thinking information to the general public.