The Global Carbon Cycle by David Archer—a review

" The climate system is an angry beast and we are poking it with sticks" - Wallace Broecker

The climate system is an angry beast and we are poking it with sticks" - Wallace Broecker

The belly of Broecker’s climate beast is surely the global carbon cycle. Currently, the beast is digesting about half of our fossil-fuel CO2 emissions, acting as a major stabilizing influence on the climate, a negative feedback. But as Professor David Archer warns us in his latest book, The Global Carbon Cycle, the carbon cycle behaves unpredictably in different circumstances and over different timescales. For example, during the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM), it acted to bring things back to the then hothouse normal after a massive belch of carbon into the atmosphere. At other times, it amplified small temperature perturbations into climate events that changed the face of the planet, as it did in the ice age cycles, the period we are still currently in. Humans are administering a perhaps PETM-scale dose of carbon into the atmosphere during a time when the global carbon cycle has acted as an amplifier rather than a damper. Ominously, Archer tells us, the planet’s reservoirs of carbon in the form of peat, gas hydrates and rain-forest carbon are now probably as charged up as they can be. That's some beast; some stick.

A continuing negative feedback carbon cycle response, in conjunction with restraint on human emissions, plus some luck with experiencing the lower ranges of climate sensitivity, could lead to climate change of, let’s say, 2°C. A future strong positive feedback from the carbon cycle, on the other hand, could add as much CO2 to the atmosphere as humans have, leading to temperature increases well beyond the International Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) upper limits. (The models used in the IPCC projections don’t generally deal with slow feedbacks from the carbon cycle— they are considered too uncertain to quantify.) Therefore, subject both to our own choices and equally to the whims of the global carbon cycle, the effect of climate change on our civilization could range from merely disruptive to unendurable. Quite obviously, biogeochemistry is a subject we should pay attention to.

The Primer

Archer’s book is the first of eight planned books in the Princeton Primers in Climate series. These short books are aimed at “students, researchers and scientifically minded general readers”. The publisher offers a free download of the first chapter of The Global Carbon Cycle here.

David Archer is one of the best writers on climate science. His introductory textbook Global Warming: Understanding the Forecast is a lucid introduction to the physics and chemistry of climate science. His subsequent book The Long Thaw: How Humans Are Changing the Next 100,000 Years of Earth's Climate—it covers some of the same ground as The Global Carbon Cycle—was written with the general reader in mind and is probably the best book of the three to start with for those new to the subject. Archer writes clearly, using quirky metaphors and a lively style that is entertaining as well as instructive.

The Global Carbon Cycle contains some twenty-two “Boxes” that delve more deeply into specific background topics. Some of these boxes are more than six pages long and tend to disrupt the flow of the main text. They are essential reading, however. Many of the boxes explain aspects of the complicated chemistry of the carbon cycle. For those of us whose last chemistry lesson is but a dim memory and whose knowledge of pH systems and redox reactions is, well, basic and rusty, fully understanding all of this can be a struggle. The box on "The Carbon Cycle Orrery" is particularly helpful, providing an imagined physical model of vessels and interconnecting tubes that helps the learner visualize how the moving parts of the the marine carbon cycle work together.

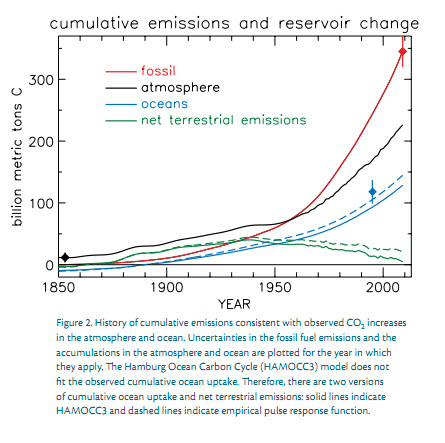

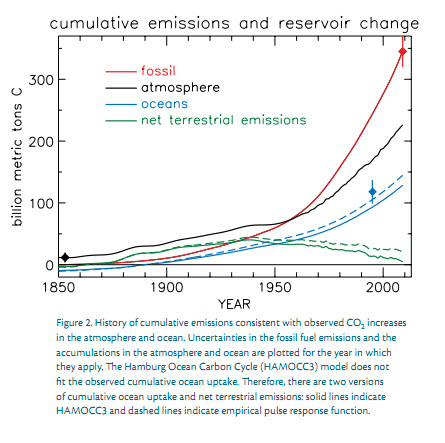

The main shortcoming of the book is in the quantity and quality of most of the graphics. Many are taken directly from other publications and have inadequate captions or explanations in the accompanying text (an exception is Figure 10, an artist's conception of the carbon cycle orrery). For example, his Figure 7 is taken from a Nature Geoscience paper by Le Quere (2009)—more correctly, Le Quéré et al. (2009)—in which Figure 7A shows indistinguishable lines relating to IPCC scenarios and Figure 7B refers to “Annex-B” and “non-Annex B” emissions histories, which, Google tells us, is a Kyoto Protocol definition. There are also some minor errors in the labelling of the y-axes in Figure 3, which, incidentally, is the same graph shown in Figure 12 in The Long Thaw, where it is correctly labelled.

One of the best features of the book is that Archer is very straightforward in detailing many of the unsolved scientific problems relating to the carbon cycle. I offer brief summaries of some of them below.

Unsolved mysteries

It’s astonishing to step back and contemplate how much has been learned about the Earth’s past. There are some detailed pages of information that have been meticulously reconstructed after having passed through the cross-cut shredder of geological history: the information from ice cores and the deep sea sediment cores are obvious examples. Yet, there are important chapters missing and many pages are only partly legible. Mysteries remain and here’s a sketch of Archer’s account of some of them.

The source of the PETM carbon “burp”. We know that the carbon was isotopically light, meaning that it came from an organic source rather than from calcium carbonate. The usual prime suspect is methane hydrate, released from deep ocean sediments. However, the biogenic methane in the hydrates is very isotopically light, meaning that the amount needed to explain the lightening of the carbon in the atmosphere would have been too little to have caused the inferred temperature change of 5°C. So, we have insufficient evidence to pin this event on hydrates, unless they had an accomplice, perhaps in the form of much higher climate sensitivity in the early Eocene hothouse than today.

The carbon feedbacks of the unstable ice age cycles. We know that the triggers for the glacial events were the orbital variations known as Milankovitch cycles, which caused small variations in temperatures in high, northern latitudes. The temperature changes which were then amplified by the carbon cycle, with more CO2 released from the atmosphere during the warming phase and more removed as things cooled. The isotope record shows that the biosphere contains less carbon during the cold times than during the hot times, thus the biosphere acted as negative feedback during the ice age cycles, an innocent bystander. Those of us who have observed that a warm beer loses more of its fizz than a cold one may be tempted to believe that the CO2/water temperature/solubility relationship is sufficient to explain the glacial era feedbacks. However, the physical chemistry is well enough understood that this effect only explains about one third of the feedback mystery. Among the many additional suspects is the “biological pump”, whereby chemically fertilized plankton bloom, die and their carbon sinks to the ocean bottom. It seems that the ice-age feedbacks were not caused by an agent acting alone but were instead the result of a conspiracy of multiple actors.

The missing sink. Since 1935, the terrestrial biosphere has been taking up carbon at a rate of more than 1Gton per year: see the figure below from

Tans (2009). But we don’t know for sure where all this carbon has gone. To give us a feel for what this large number means, Archer tells us that the (literal) mass of humanity (everything, not just our carbon) is about 0.5Gton. So, every year, Mother Nature is burying the equivalent an awful lot of bodies somewhere, most likely in the high northern latitudes. The probable mechanisms include: increased plant growth in the tundra due to the warming climate; reforestation; and fertilisation by increased CO

2 in the air or the nitrate in acid rain.

This is a brief and partial outline of just some of the topics covered in The Global Carbon Cycle. Read the book to get a complete account.

Tans (2009)

Spoiler alert

Even though David Archer has written a book full of mysteries, there is, alas, no final scene where a Miss Marple figure assembles all the suspects in the drawing room, dispatches all the red herrings and finally unmasks the perpetrator: It was you, Professor Milankovitch, on the Continental Slope, with the Clathrate Gun! So, I can safely quote the last chapter in full without spoiling the story.

"It is premature even to attempt to guess how strong the overall carbon cycle feedback on climate change might be, but my hunch is that, in the worst case scenario, the carbon cycle feedback might eventually release as much CO2 as humans do, a sort of “matching funds” arrangement. If the carbon cycle feedbacks in general were much stronger than that, the climate system would be so unstable it would have melted down in the geologic past more frequently than it apparently has. But Earth’s biosphere and carbon cycle are vastly more creative than human imagination is able to anticipate, so don’t take my word for any of this. We’ll have to wait and see."

Posted by Andy Skuce on Tuesday, 15 February, 2011

The climate system is an angry beast and we are poking it with sticks" - Wallace Broecker

The climate system is an angry beast and we are poking it with sticks" - Wallace Broecker