This is a re-post from Andrew Dessler at the Climate Brink blog

In 2023, the Earth reached temperature levels unprecedented in modern times. Given that, it’s reasonable to ask: What’s going on? There’s been lots of discussions by scientists about whether this is just the normal progression of global warming or if something we don’t understand is happening — in other words, we’ve broken the climate.

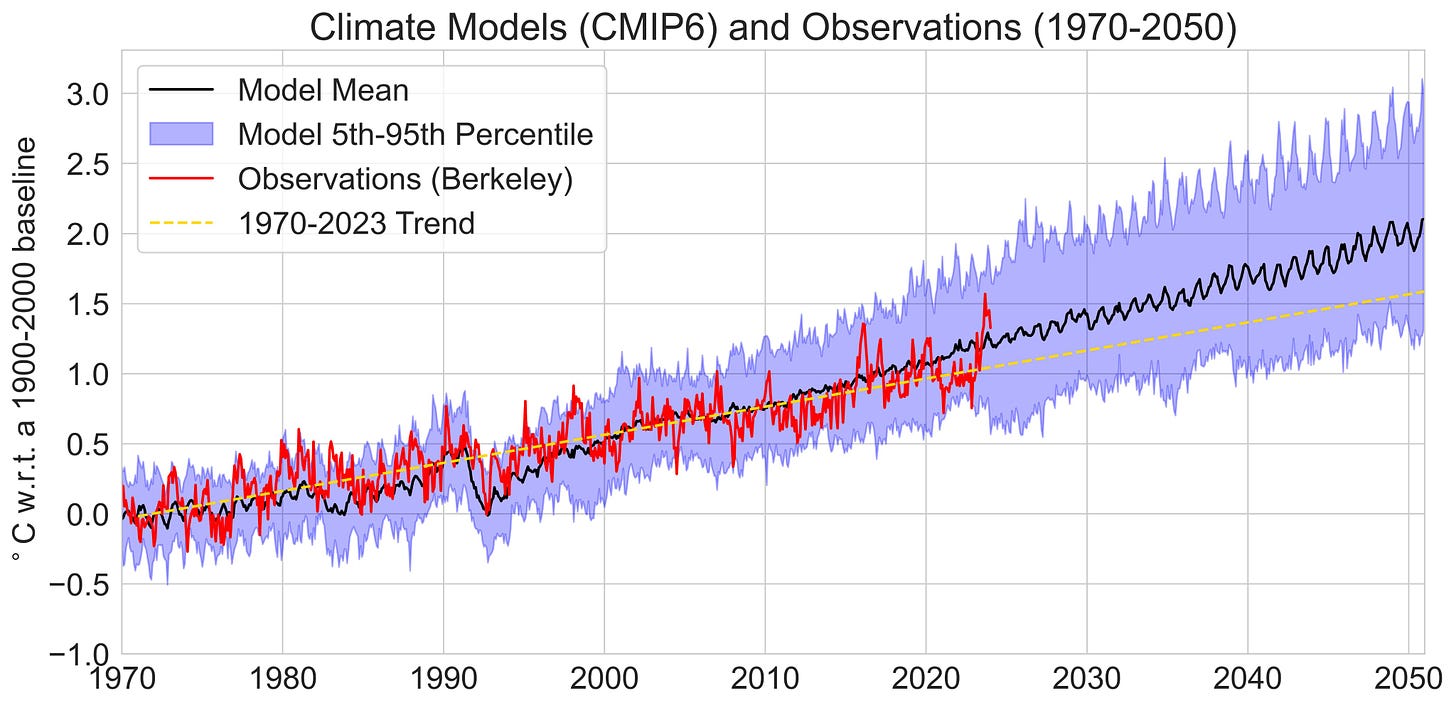

In this post, I compare the observational temperature record to an ensemble of state-of-the-art CMIP6 models to see exactly how unusual 2023 was. It turns out that 2023 is just not that unusual when compared to the model ensemble.

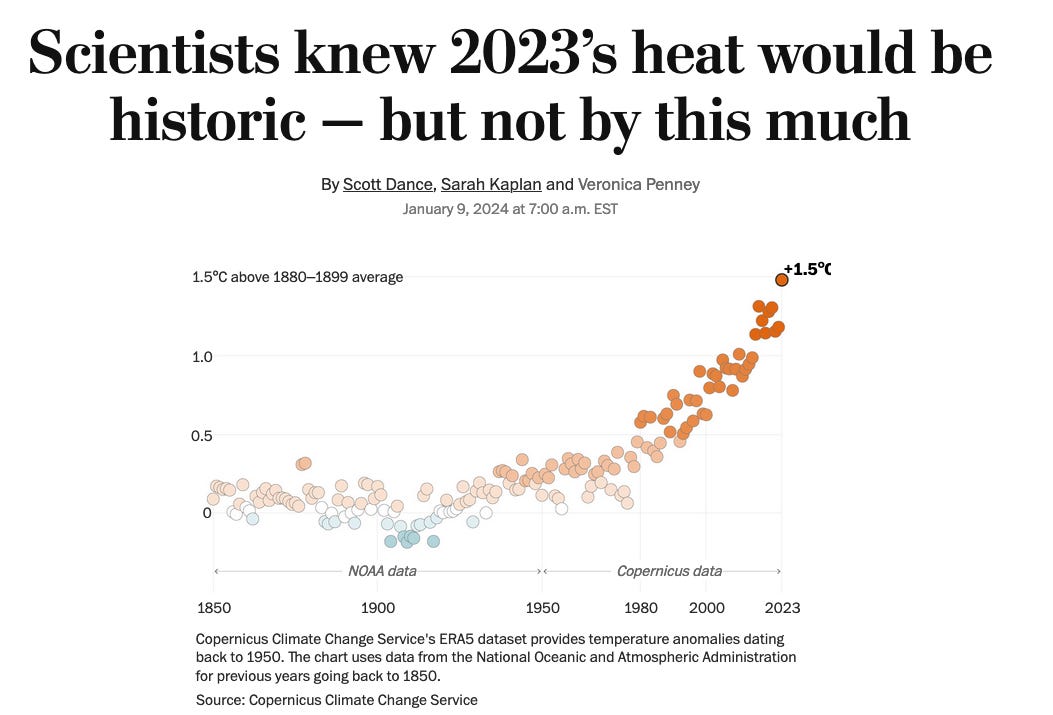

Let’s start with observations. I’m going to be using the Berkeley Earth global average temperature data. In that data set, 2023 was a record-breaking 1.54C above the 1850-1900 average temperature. This temperature exceeded the previous record (set in 2016) by 0.17C.

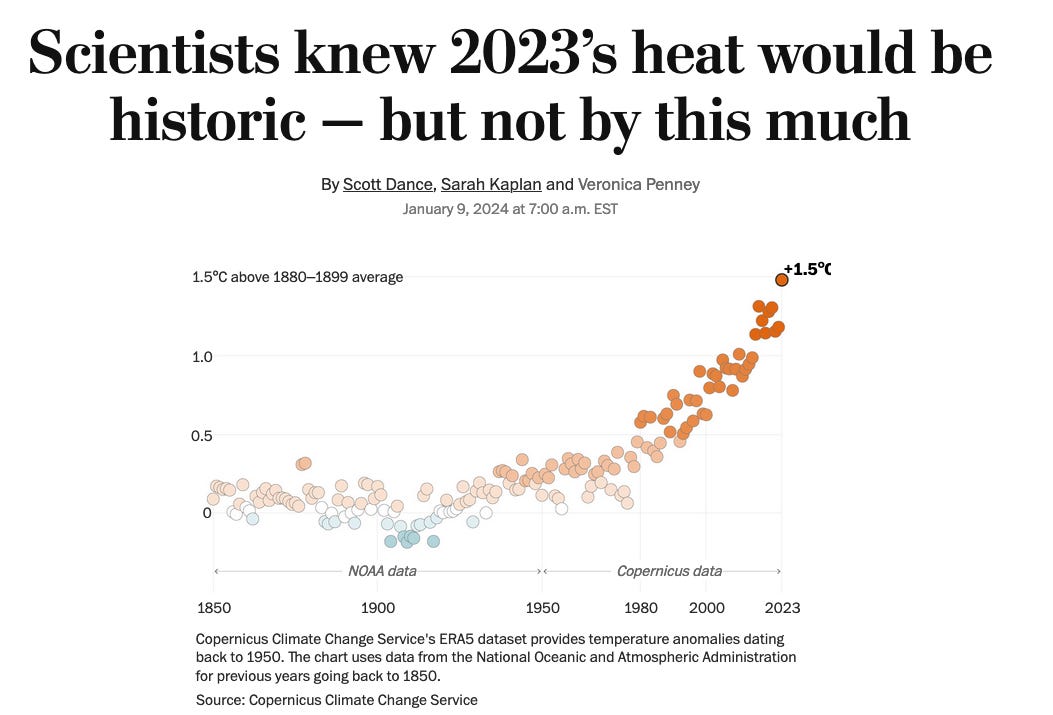

Beating the previous record by 0.17C is huge: if we look at the temperature observations since 1970, the margin by which records were broken averaged 0.07C, with a median of 0.05C. And no record in the last 50 years had a margin larger than 0.17C.

What does the climate model ensemble show? I have analyzed 38 CMIP6 models over the period 1970-2030 driven by historical and SSP4.5 forcing. Here is a plot of the biggest margin for a record year vs. the year that record occurred:

As you can see, the record-breaking margin of 2023, 0.17C, was actually quite modest compared to the climate model ensemble. One model had a year that broke the previous record by nearly 0.45C — all I can say is holy crap, let’s hope that doesn’t happen in the real world.

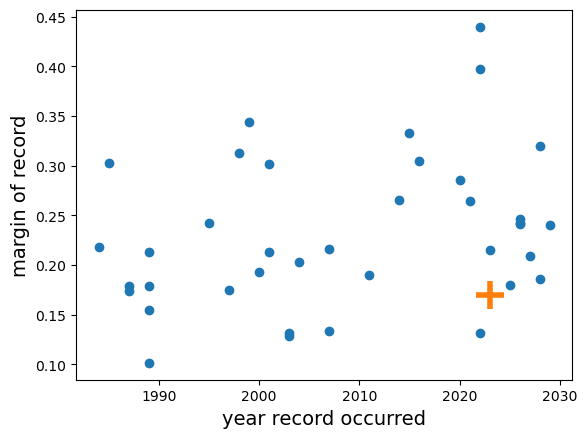

A lot was also made of the fact that 2023 was the first year with a global average temperature anomaly to exceed 1.5C (in some data sets, at least). How unusual is that? Again, we can look at the models to see when they had their first year above 1.5C (as before, relative to the 1850-1900 baseline)1.

The median date for the model ensemble to have its first year above 1.5C is 2024, very close to when we actually did (2023). Thus, the model ensemble seems to be simulating the warming pretty accurately. And the ensemble does equally well for a more modern baseline, like 1970-1990.

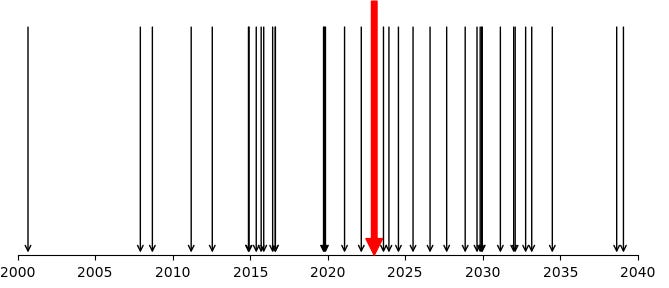

Many others have looked at different aspects of the problem and reached similar conclusions. Here’s a plot that Zeke posted on Twitter that shows that the observed temperature time series still falls within the range of models.

This doesn’t mean we know everything about the climate of 2023. The extreme warmth was definitely surprising given the state of the climate in 2022, so important work remains to be done on understanding the physical mechanisms that were driving this record-breaking year.

But the real test of our climate understanding will come in the next few years. If global temperatures drop after the current El Niño fades, as expected, 2023’s high temperatures will be seen as an unusual blip in the long-term evolution of the climate (like “the pause” that occurred in the 2000s). However, if temperatures stay high or, heaven forbid, keep rapidly warming, it would suggest that we’ve broken the climate system. Let’s hope that doesn’t happen.

Posted by Guest Author on Wednesday, 17 April, 2024

|

The Skeptical Science website by Skeptical Science is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. |