Lessons from Past Climate Predictions: William Kellogg

In 1979, William Kellogg authored an extensive review paper summarizing the state of climate modeling at the time. Among the studies referenced in Kellogg's work was Wallace Broecker's 1975 study which we previously examined in the Lessons from Past Climate Predictions series.

In 1979, William Kellogg authored an extensive review paper summarizing the state of climate modeling at the time. Among the studies referenced in Kellogg's work was Wallace Broecker's 1975 study which we previously examined in the Lessons from Past Climate Predictions series.

General Climate Model Review

Kellogg's review discussed the fact that in the late 1970s, climate models were still relatively simple and excluded or did not accurately reflect some important feedbacks (such as cloud cover changes); however, they did include the feedback from albedo (reflectivity) changes due to retreating or advancing ice in response to changing temperatures.

As in Broecker's 1975 study, Kellogg correctly identified that carbon dioxide represents the most significant human impact on the global climate. However, Kellogg also stated with a fair amount of confidence that aerosols should have a net warming effect on the climate because not only do they scatter sunlight, but they also absorb it, and Kellogg believed the latter effect was stronger than the former. However, based on up-to-date climate research, aerosols certainly have a net cooling effect, and possibly a very strong one.

Kellogg (1979) Temperature Prediction

In the paper, Kellogg predicted future polar and global surface temperature changes (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Kellogg (1979) average polar and global temperature predictions based on exponential CO2 growth (high) and decreasing growth rate (low). Gray region represents the approximate global temperature over the previous 1,000 years, and the dashed line represents the approximate average global temperature if humans had not increased atmospheric CO2.

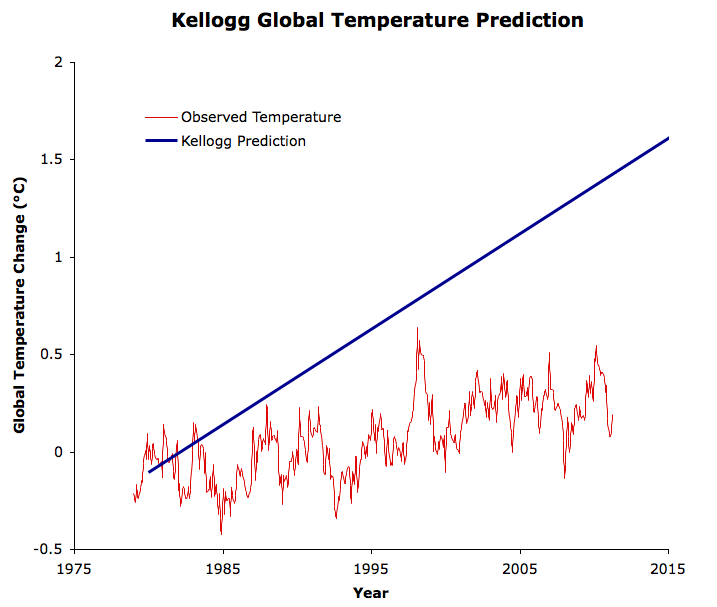

Strangely, Kellogg predicted that future temperatures will increase in linear fashion, even though he projected essentially the same exponential atmospheric CO2 increase as Broecker did in his 1975 study. We digitized Kellogg's "high" predictions, since CO2 has increased at a similar exponential rate to this scenario, and compared it to the Wood for Trees Temperature Index (a composite of GISTemp, HadCRUT3, UAH, and RSS temperature data sets) (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Kellogg global temperature prediction vs. observed temperature changes according to the Wood for Trees Temperature Index.

Kellogg's Flaws

Clearly Kellogg significantly overestimated the ensuing global warming - much more so than Broecker a few years earlier. So what went wrong? Kellogg stated that the climate sensitivity in most models was consistent with Broecker's:

"The best estimate of the "greenhouse effect" due to a doubling of carbon dioxide lies between 2 and 3.5°C increase in average surface temperature (Schneider 1975, Augustsson & Ramanathan 1977, Wang et al 1976), and both the models and the record of the behavior of the real climate show that the change in the polar regions will be greater than this by a factor of from 3 to 5, especially in winter"

This climate sensitivity is also broadly consistent with that of today's climate models of 2 to 4.5°C for doubled atmospheric CO2. However, Kellogg's temperature prediction used a model with higher sensitivity than his above stated range:

"When the level of carbon dioxide has risen to 400 ppmv from its present 330 ppmv, the rise in average surface temperature is estimated to be about 1°C. These figures refer to the effect of carbon dioxide alone"

An average global temperature response of 1°C to a CO2 increase of 330 to 400 ppmv corresponds to a climate sensitivity of 3.6°C. However, Kellogg assumed that this temperature response would be instantaneous, with the average global temperature warming 1°C by the time atmospheric CO2 levels reached 400 ppmv (by the year 2011 in his estimation).

An instantaneous temperature response represents a transient climate sensitivity, which according to current climate research, is approximately two-thirds as large as equilibrium climate sensitivity. Therefore, the equilibrium sensitivity employed in Kellogg's prediction is approximately 5.4°C, which is quite high, and above the IPCC likely range of equilibrium climate sensitivity values.

Kellogg also included the warming effects of other greenhouse gases (such as methane) in his model, but did not include the cooling effects of aerosols (which as noted above, Kellogg believed had a net warming effect as well). By including the warming effects of other greenhouse gases, the equivalent CO2 concentration in Kellogg's model reached 400 ppmv by 2000, causing him to overestimate the rate of warming even further.

It's important to note that because Kellogg's prediction was linear while the actual temperature increase will be exponential, the further ahead in time we go, the more accurate Kellogg's prediction will become. In 2050 it will be less unsuccessful than in 2011, but due to the high sensitivity of his model, the actual temperature will still be below Kellogg's prediction.

Kellogg's Success

Kellog was quite accurate in one aspect of his prediction: polar amplification. Average Arctic surface temperature has increased approximately 3°C since 1880 and approximately 2°C since 1970. This is a warming rate approximately 3.6 times faster than the average global surface warming, which is within Kellogg's predicted polar amplification range of a factor of 3 to 5.

Lessons Learned

Although his global warming prediction was inaccurate, we can learn a great deal from Kellogg's work. The reasons for his inaccuracy were:

-

Kellogg assumed a linear temperature increase in response to an exponential CO2 increase.

-

Kellogg modeled the warming effects of non-CO2 greenhouse gases, but did not model the cooling effects of aerosols. In fact, he thought aerosols would have a net warming effect, which we now know is not the case.

- The main lesson to take away from this study is that Broecker's model - with a transient climate sensitivity of 2.4°C and an equilibrium sensitivity of approximately 3.6°C - predicted the ensuing global warming much more accurately than Kellogg's model - with a transient sensitivity of 3.6°C and an equilibrium sensitivity of 5.4°C for doubled CO2.

Implications

The good news is thus that while there is no credible evidence that climate sensitivity is low, it does not appear to be exceptionally high. The bad news is that it still appears to be close to the IPCC most likely value of 3°C for doubled CO2, which still means we're in for some nasty consequences if we continue on a business-as-usual path. At the end of his paper, Kellogg addresses the challenges we face:

"Action on the part of the community of nations could only ensue if two things occurred: first, the climatologists, economists, social scientists, and politicians must understand the future clearly enough to decide that a global warming would indeed be too costly to mankind as a whole to be "acceptable" (a value judgment in the last analysis); and, second, there must be the international machinery to make the final decision to act and to enforce the decision. No such machinery exists, nor do we even see how to set it up"

While the first criterion has essentially been met, and there is widespread agreement amongst all the listed parties that continued global warming presents an unacceptable risk, enforcing the decision to reduce global carbon emissions internationally remains a major challenge which we have begun to address through international climate conferences. But we still haven't quite cracked that nut, and time is running out.

Posted by dana1981 on Wednesday, 20 July, 2011

In 1979, William Kellogg authored an extensive review paper summarizing the state of climate modeling at the time. Among the studies referenced in Kellogg's work was Wallace Broecker's 1975 study which we previously examined in the Lessons from Past Climate Predictions series.

In 1979, William Kellogg authored an extensive review paper summarizing the state of climate modeling at the time. Among the studies referenced in Kellogg's work was Wallace Broecker's 1975 study which we previously examined in the Lessons from Past Climate Predictions series.