What The Science Says:

The wind turbines require less land per kilowatt-hour generated than fossil fuels and the land required for net-zero emissions will have a notably smaller footprint than the 4.4 million acres currently used for natural gas extraction and the 3.5 million acres for oil extraction.

Climate Myth: Wind turbines take up too much land

"The wind’s low power density means massive materials and land/sea area requirements." (Wind Watch)

Princeton University’s 2021 report, Net-Zero America, concluded that the wind turbines needed for the United States to reach net-zero emissions by 2050 will have a direct footprint (i.e., the area covered by turbine bases and access roads) of between 603,678 and 2,479,208 acres.1 This is notably less than the 4.4 million acres currently used for natural gas extraction and the 3.5 million acres for oil extraction.2

Some analyses significantly overstate the amount of land required for wind energy, either by including the unused space between turbines or by using a metric called the visual footprint that measures the area from which turbines are visible. As Amory Lovins has stated, “Saying that wind turbines ‘use’ the land between them is like saying that the lampposts in a parking lot have the same area as the parking lot: in fact, about 99 percent of its area remains available to drive, park, and walk in.” (Lovins 2011) When a wind turbine is sited on farmland, it typically uses only about 5% of the project area, leaving the rest available for agriculture and other purposes.3

Moreover, depending on the location and the technology used, wind turbines can also require less land per kilowatt-hour generated than fossil fuels. A report by the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) found that total land occupation (agriculture and urban) for wind power ranged from 0.3–1 m2/KWh for 2022. The exact value depends on the type of wind tower, onshore or offshore siting, and the particular location of the turbine. By comparison, natural gas values ranged from 0.6–3.3 m2/KWh, and coal values from 7.2–23.8 m2/KWh. The UNECE report notes that these calculations do not include carbon capture and storage (CCS), which, if implemented, would decrease emissions but increase land use.4

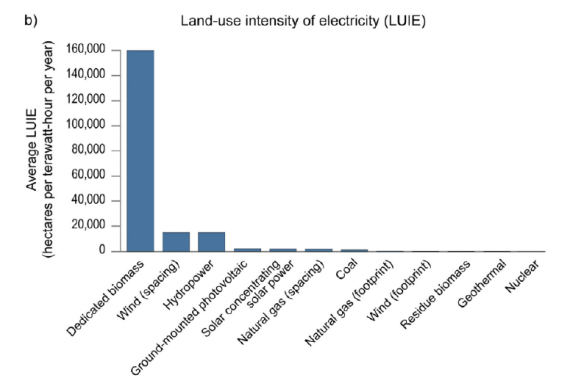

Wind energy also uses far less land than biomass. Dedicated biomass consumes an average of 160,000 hectares of land per terawatt-hour per year. By contrast, the land-use intensity of wind energy is only 170 hectares per terawatt-hour per year when looking at the direct footprint of wind or 15,000 hectares per terawatt-hour per year when including space between turbines (Lovering et al. 2022).

Figure 1: Average land-use intensity of electricity, measured in hectares per terawatt-hour per year. Source: U.S. Global Change Research Program (visualizing data from Lovering et al. 2022).

Fossil fuel generation also has more harmful and enduring impacts on the land that it uses. Spills frequently occur as a result of the extraction, transportation, and distribution of oil and natural gas, causing soil and water damage. A 2017 study found that between 2% and 16% of unconventional oil and gas wells reported a spill each year, with more spills in some states than others (Patterson et al. 2017). Reclamation is difficult in areas surrounding extraction sites because of frequent leakage (Allred et al. 2015). The land involved often suffers long-term damage and can only be used for limited purposes. Moreover, abandoned coal mines and orphaned oil and gas wells can continue to threaten public health by contaminating groundwater, emitting methane and other noxious gases, and, in the case of abandoned coal strip mines, even result in continuing risk from falling boulders.5 There are currently over 130,000 documented orphaned oil and gas wells in the United States6; in one state, Kentucky, nearly 40% of purportedly “active” coal mines are “functionally abandoned.”5

By contrast, utility-scale wind farms can be incorporated into America’s pasture and cropland with significantly less disturbance. Wind farms directly occupy relatively small amounts of land. According to the Department of Energy, powering 35% of our national electric grid through wind turbines would require 3,200 km2 (790,000 acres) of land, a small fraction of the United States’ 2.3 billion acres of land.7 Furthermore, there is ample space for additional land uses within wind farms: the National Renewable Energy Laboratory estimates that about 98% of the area in a wind farm is available for agriculture or other uses.8 Moreover, plant and animal species can safely grow and roam directly up to a turbine’s base. This can help native species to flourish, as well as allowing farmers to continue cultivating crops and grazing animals after wind projects are installed.9 And reclamation of wind (and solar) energy sites can begin as soon as plants begin operation, because wind and solar require only small amount of soil disturbance compared to other energy sources (Dhar et al. 2020).

Finally, climate change produced by burning fossil fuels directly harms forests, oceans, crops, and wildlife, including by causing wildfires, algal blooms, droughts, and extreme weather events that mar the visual landscape.10 Wind energy, in contrast, further protects local landscapes by mitigating climate impacts.

Footnotes:

[1] Eric Larson et al., Net-Zero American: Potential Pathways, Infrastructure, and Impacts: Final Report, Princeton University, 247 (Oct. 29, 2021) at 245. The report predicts that the “total wind farm area” will be significantly larger, but these numbers include the entire visual footprint of wind farms.

[2] Dave Merrill, The U.S. Will Need a Lot More Land for a Zero-Carbon Economy, Bloomberg (June 3, 2021).

[3] McGill University, Clearing the air: Wind farms more land efficient than previously thought, ScienceDaily, Apr. 17, 2024.

[4] Carbon Neutrality in the UNECE Region: Integrated Life-cycle Assessment of Electricity Sources, United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE), United Nations, 70 (2022).

[5] See Orphaned Wells, U.S. Dep’t of Interior (last visited Apr. 1, 2024); James Bruggers, Congressional Office Agrees to Investigate ‘Zombie’ Coal Mines, Inside Climate News, Jan. 12, 2024.

[6] Federal Orphaned Well Program, U.S. Bureau of Land Management (last visited Apr. 1, 2024).

[7] Wind Vision: A New Era for Wind Power in the United States, U.S. Department of Energy, 105 (2015) at 139; Land and Natural Resources, Economic Research Service, U.S. Dep’t of Agriculture, (last visited March 25, 2024).

[8] Paul Denholm et al., Examining Supply-Side Options to Achieve 100% Clean Electricity by 2035 at 51, Nat’l Renewable Energy Laboratory, 2022.

[9] Molly Bergen, How Wind Turbines are Providing a Safety Net for Rural Farmers, World Resources Institute (October 13, 2020).

[10] Savannah Bertrand, Fact Sheet: Climate, Environmental, and Health Impacts of Fossil Fuels, Environmental and Energy Study Institute (December 17, 2021).

[Note June 7, 2025: updated one or more link(s) to archived version(s)]

This rebuttal is based on the report "Rebutting 33 False Claims About Solar, Wind, and Electric Vehicles" written by Matthew Eisenson, Jacob Elkin, Andy Fitch, Matthew Ard, Kaya Sittinger & Samuel Lavine and published by the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia Law School in 2024. Skeptical Science sincerely appreciates Sabin Center's generosity in collaborating with us to make this information available as widely as possible.

|

The Skeptical Science website by Skeptical Science is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. |