It is not news that people are polarized over their assessment of the risks posed by climate change. But is it true that the most polarized people are those who are more scientifically literate? Counter-intuitive though it may seem, the answer is: Yes, it is. This is the result of a recent article by Dan Kahan and six colleagues in Nature Climate Change (henceforth, the Kahan Study). This study has received a lot of attention, with blog articles, for example in The Economist, Mother Jones and by David Roberts at Grist.

At Skeptical Science, our goal is to debunk false arguments and explain the science behind climate change. In the light of this peer-reviewed research, we have to ask ourselves: if we are striving to increase scientific literacy, won’t we just be making the polarization that exists around climate change worse? We will come back to that question at the end of this piece, but first, we’ll look in some detail at the Kahan Study itself.

Kahan et al identified two contrasting hypotheses that seek to explain the polarization in the public’s appreciation of the risks posed by climate change. (Note that the Kahan Study did not look at the public’s perception of the truth or reliability of climate science but, rather, the public’s assessment of the risks that climate change poses.) These hypotheses are:

These hypotheses are not necessarily mutually exclusive. Indeed, some partisans in the climate war will attribute their own beliefs to their comprehension of the science, while explaining the erroneous beliefs of the other side as being rooted in cultural factors. However, the two hypotheses do make distinct predictions about how risk perception, cultural groups and scientific literacy should be correlated; therefore, they can be tested.

Specifically, SCT would predict that, as scientific literacy increases, polarization of perceptions of the risk that climate change poses to human health and prosperity should decrease. CCT predicts that perception of environmental risk should correlate primarily with value systems rather than scientific literacy. In this model, people with a hierarchical and individualistic world-view are expected to be naturally skeptical of environmental risks, since acceptance of such risks implies the need for regulation of industry and consumption. On the other hand, those whose world-view makes them instinctively suspicious of unregulated commerce would be more inclined to accept the threat climate change poses.

A detailed description of the methods used in the Kahan Study can be viewed in the Supplemental Information. Here’s a quick summary.

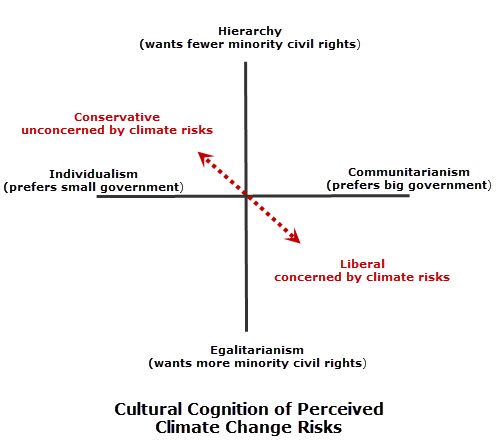

Cultural world-views were measured by where individuals fit when plotted on two axes: the Hierarchy-Egalitarian Axis and the Individualism-Communitarianism Axis. See Figure 1. All the subjects were Americans and basically (but not exactly) this analysis placed people on a liberal-conservative spectrum. Liberal-conservative terminology will be used here for simplicity.

Perceptions of risk were determined by asking subjects to rate the seriousness of climate-change risk on a ten-point scale.

Scientific and mathematical ability were estimated using the National Science Foundation’s Science and Engineering Indicators (eight questions) as well as a set of fourteen mathematical questions. As has been triumphantly reported in the Daily Mail, conservatives scored a little higher on the scientific literacy scores.

Figure1. (Adapted and simplified from Figure S2 in the Supplemental Information of Kahan et al, 2012; original figure can be seen here.) World-views are measured on two axes, based on a questionnaire. Political views and perceptions of the risks posed by climate change tend to cluster in different quadrants.

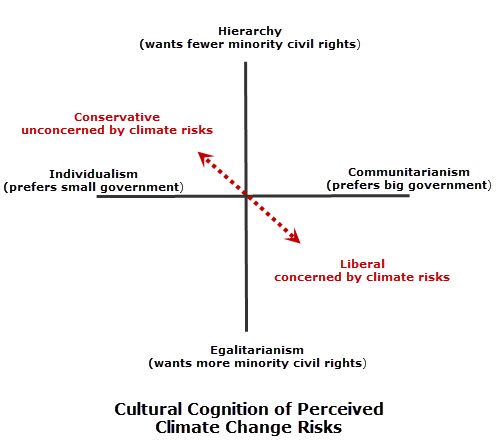

The data were subjected to multivariate regression analysis, with the science and mathematics measures being combined into a single factor. The results falsify the SCT hypothesis, increasing scientific literacy increases polarization. The main determining factor on climate risk perception is cultural, corroborating CCT.

Figure 2. (Kahan et al, 2012, Figure 2) The results quite clearly show that the prediction of the SCT model is falsified and that the perceived risk of climate change is not correlated with science literacy and numeracy. Not only is the world-view polarization on perception of climate risk evident in the right-hand graph, but this polarization actually is larger between people with opposed world-views but who have greater scientific literacy.

The widening polarization between subjects with high scientific literacy casts doubt on another prediction of the SCT hypothesis. The two-system model of mind (Daniel Kahneman’s book Thinking, Fast and Slow is highly recommended) describes our thinking as if it were working as two separate systems: system 1, which makes snap, instinctive judgements and system 2, which is the conscious, deliberative and calculating part of the mind. If we accept that system 1 instinctively responds in harmony with the subjects’ world-views, we should not be surprized that people with low scientific literacy tend to be polarized in line with their politics on technical issues such as climate change. But it would be expected under SCT that increasing scientific ability would overpower the instinctive response with the force of cold reason and dispassionate deliberation, reducing instinctive polarization. This is not the case.

One reason why this may not be so is because we have assumed that our deliberative system 2 acts as an impartial judge, using reason and argument to persuade the instinctive system 1 that its prejudices are wrong. In fact, system 2 can act not as an impartial judge but as a lawyer, arguing a case on behalf of its client, system 1. A model like this has been proposed by Mercier and Sperber (2011) who assert that we use reason not so much to improve knowledge and to make better decisions, but instead to make arguments to persuade others—and ourselves—that our instincts are right. The weaker the case, the harder the system 2 lawyer must work to get an acquittal.

Chris Mooney, in his recent book, The Republican Brain: The Science of Why They Deny Science--and Reality explores some of the differences in the psychology and reasoning between American liberals and conservatives. One observation that he makes is that, even though everyone has their prejudices and blind spots, liberals tend to be relatively more open-minded and more easily persuaded by new arguments. As a Daily Kos review of Mooney's book put it:

One manifestation is modern-day conservatives are more difficult to persuade than non-conservatives using documented facts or reasonable inferences, particularly on issues where there's a partisan axis, even in the face of a robust scientific consensus or just plain common sense.

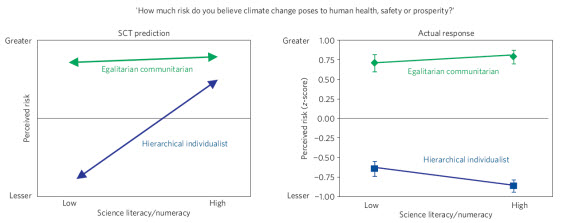

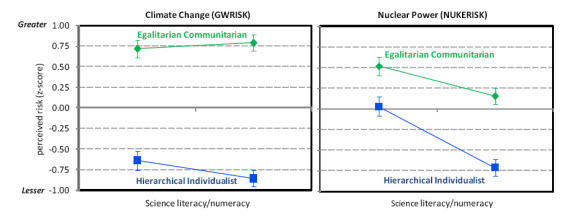

Figure 3. (From the Supplemental Information of Kahan et al, 2012.) Comparing liberal and conservative assessments of the risks of climate change and nuclear power and showing how these responses vary with different levels of scientific literacy. Even though polarization increases with scientific knowledge in both cases, the degree of polarization is mainly driven by scientifically literate conservatives perceiving less risk in both cases.

The response of liberals to nuclear risks suggests that, in this case, liberals reduce their perception of risks away from the instinctive liberal position, the more scientifically literate they are. In contrast, scientifically literate conservatives tend to dig in deeper on both climate and nuclear risks. Perhaps this supports Mooney’s idea that liberals can be more easily persuaded away from their instinctive positions. It also suggests that for some subsets of people (scientifically literate liberals and less scientifically literate conservatives) and for some issues (nuclear power risks), the CCT hypothesis fails, but this is not a conclusion that Kahan et al have drawn from their work.

The following points are my own observations. This is in a field that I am not very familiar with, so beware the Dunning-Kruger effect!

None of this is intended to challenge the Kahan Study itself. But what the study does not show is that attempting to increase an individual's knowledge of climate science necessarily causes that individual's instinctive views, pro or con, to become more extreme.

Despite this, it’s quite clear from the Kahan Study that there is nothing to support the idea that instinctive skeptics are likely to become persuaded of the urgency of the climate change problem by scientific education alone. So, if our goal is for the majority of the population to become concerned about climate change, what is to be done?

Kahan et al argue that it can be costly for an individual to change their mind on a polarized issue such as climate change. Holding certain beliefs is a condition of belonging to cultural groups. Adopting a position contrary to your peer group can threaten your social status, while having little effect on the collective opinion. They called this a “tragedy of the risk-perception commons”, in reference to Garret Hardin’s seminal idea from the 1960’s, according to which, in certain settings, individuals acting rationally in their individual interest produce a collective failure.

The conclusion of the Kahan Study reads as follows:

[…] simply improving the clarity of scientific information will not dispel public conflict so long as the climate-change debate continues to feature cultural meanings that divide citizens of opposing world-views.

It does not follow, however, that nothing can be done to promote constructive and informed public deliberations. As citizens understandably tend to conform their beliefs about societal risk to beliefs that predominate among their peers, communicators should endeavor to create a deliberative climate in which accepting the best available science does not threaten any group's values. Effective strategies include use of culturally diverse communicators, whose affinity with different communities enhances their credibility, and information-framing techniques that invest policy solutions with resonances congenial to diverse groups. Perfecting such techniques through a new science of science communication is a public good of singular importance.

There’s little doubt that “culturally diverse communicators” can be effective. Examples of such climate science communicators would include Katharine Hayhoe (Evangelical Christian), Kerry Emanuel (Republican) and Barry Bickmore (Mormon apologist), all of them scientists and communicators who are effective in addressing conservatives. They are effective not only because of what they say and how well they say it, but also because of who they are.

A particularly powerful video by Peter Sinclair is one in which senior US military commanders speak about the climate crisis as a threat to US national security that requires military preparedness. The video is effective, not because the arguments the military officers make are especially insightful from a scientific standpoint, but because of who they are and because of the values that they represent.

Dan Kahan is a professor of law at Yale University. He has been an advocate of a Gentle Nudges vs Hard Shoves approach to enforcement of laws designed to change social norms, on issues such as date rape and drunk driving. He also wrote an article in Nature in 2010, Fixing the Communication Failure (open source here) on cultural cognition. He wrote:

[...] people find it disconcerting to believe that behaviour that they find noble is nevertheless detrimental to society, and behaviour that they find base is beneficial to it. Because accepting such a claim could drive a wedge between them and their peers, they have a strong emotional predisposition to reject it.

And, as a solution:

It would not be a gross simplification to say that science needs better marketing. Unlike commercial advertising, however, the goal of these techniques is not to induce public acceptance of any particular conclusion, but rather to create an environment for the public's open-minded, unbiased consideration of the best available scientific information.

As straightforward as these recommendations might seem, however, science communicators routinely flout them. The prevailing approach is still simply to flood the public with as much sound data as possible on the assumption that the truth is bound, eventually, to drown out its competitors. If, however, the truth carries implications that threaten people's cultural values, then holding their heads underwater is likely to harden their resistance and increase their willingness to support alternative arguments, no matter how lacking in evidence. This reaction is substantially reinforced when, as often happens, the message is put across by public communicators who are unmistakably associated with particular cultural outlooks or styles — the more so if such advocates indulge in partisan rhetoric, ridiculing opponents as corrupt or devoid of reason. This approach encourages citizens to experience scientific debates as contests between warring cultural factions — and to pick sides accordingly.

Kahan's consistent message is that you won't get through to people with a reasoned argument if you provoke them and they raise their cultural defences.

Let’s return to the question posed at the beginning. Since Kahan et al have shown that increasing scientific literacy correlates with increases polarization on climate, are we, at Skeptical Science, doing more harm than good by focussing on rebutting climate myths and explaining new science?

Probably not.

To recap: The Kahan Study did not show that providing more information on climate science causes more polarization, just that, in the contemporary United States at least , polarization on the issue is mostly driven by cultural identity, and that the scientifically literate, as they defined those people, tend to be the most polarized of all. Kahan recommends that the most effective and persuasive approach is to, above all, avoid threatening people's cultural norms.

SkS authors are a fairly diverse bunch but we are like-minded people from developed countries with science degrees. We probably do not meet Kahan’s ideal of being “culturally diverse communicators”. Although we try to keep most of our discussions politically neutral, we can’t avoid politics when discussing solutions and sometimes our personal political biases will be evident.

We are well aware that our blog readership mostly comprises people who have already made up their minds (see David Roberts; see also a video on this Preaching to the Converted by Theramin Trees). Occasionally, we hear from individuals who have changed their mind with the help of Skeptical Science, but those instances are rare. Our blog is endorsed by several scientists, some of whom read it regularly to catch up on news outside their speciality.

Even if we are mainly communicating with those already convinced by the evidence, we hope that there is some value in providing arguments and explanations that readers can use when they discuss climate change with family and co-workers. We hope, in effect, that our readers fill the role of "diverse communicators", using their adaptations of our arguments within their own communities, workplaces and families.

We know that we are unlikely to win over many hard-core contrarians with our rebuttals or blog posts. In reality, our target audience is that large group of people who are not yet committed or engaged. We hope that people who have questions about climate change will come here via a Google search or a reference from somewhere else. Our basic rebuttals, in particular, are aimed at people new to the climate discussion and are intended to nip misinformation in the bud.

But it’s not up to us to decide how effective we are. We can do better. For that we need feedback. So please take the time and tell us in the comments what we are doing well and what we are doing badly; what we do too much of, or too little of.

Posted by Andy Skuce on Friday, 15 June, 2012

|

The Skeptical Science website by Skeptical Science is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. |