Rex Tillerson is the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of ExxonMobil. In 2006 he replaced Lee Raymond, who was its CEO from 1999 through 2005, during which time he denied the reality of climate change and ExxonMobil spent tens of millions of dollars funding climate change denial groups like the Heartland Institute. Raymond's ExxonMobil also paid for expensive, weekly "Opinion Advertorials" on the New York Times opinion pages disputing mainstream climate science.

In 2008, under Tillerson's watch, ExxonMobil pledged to cut funding to several climate denial groups. The company does continue to fund some climate contrarians like Willie Soon; however, Tillerson has certainly been an improvement over Raymond in terms of climate realism, and he does acknowledge that human greenhouse gas emissions are causing global warming. Tillerson seemed to have changed ExxonMobil's stripes on climate change.

However, Tillerson recently gave a speech to the Council on Foreign Relations (video here, transcript here) which not surprisingly, since he's a fossil fuel company CEO, centered around assertions that we have tons and tons of oil and natural gas reserves remaining. During the question and answer session, an audience member asked him this question about the climate implications of burning these immense quantities of fossil fuels:

"You know, if we burn all these reserves you've talked about, you can kiss future generations good-bye. And maybe we'll find a solution to take it out of the air. But, as you know, we don't have one. So what are you going to do about this? We need your help to do something about this."

As might be expected from a fossil fuel company CEO, Tillerson responded to this question by downplaying the threat posed by climate change, but as we will see in this post, he misrepresented the state of climate science and economics research in the process, and advocated a rather foolhardy approach to risk management.

Tillerson's first response to the climate threat question was to emphasize uncertainty by disputing the accuracy of climate models:

"I'm going to take exception to something you said -- the competency of the models to predict the future. We've been working with a very good team at MIT now for more than 20 years on this area of modeling the climate, which, since obviously it's an area of great interest to you, you know and have to know the competencies of the models are not particularly good."

Climate models are of course not perfect, and Tillerson identified two specific challenges they face - the uncertainty regarding the size of the cooling effect aerosols have on the climate, and the response of clouds in a warming world.

That being said, climate models have accurately simulated a number of observed climate changes. Additionally, the larger our greenhouse gas emissions, the more confident we can be that they will result in large and bad climate change consequences, and Tillerson is essentially advocating that we burn through all known fossil fuel reserves. If we do, we can be confident that the consequences will very likely be disastrous. As Ronald Prinn, director of the Center for Global Change Science at MIT noted in response to Tillerson's comments,

"The models are certainly good enough to clearly show the benefits of mitigation policies compared to no policy, in lowering risks. We cannot wait for perfection in climate forecasts before taking action."

Tillerson proceeded to further emphasize climate uncertainties:

"when you predict things like sea level rise, you get numbers all over the map."

It's important to remember that uncertainty cuts both ways. It means that we can't rule out the possibility that the consequences of climate change will be relatively benign, but we also can't rule out the possibility that they will be utterly catastrophic. Uncertainty is no excuse for inaction, and is certainly not a justification for foolish optimism.

In fact, when doing proper risk management, it's important to look at the full range of scenarios, including the worst case. To follow Tillerson's example, there is a large range of potential future sea level rise, with the worst case scenario exceeding 1 meter by 2100. Such a large sea level rise would have very costly impacts, and the more fossil fuels we consume, the larger that sea level rise will be.

Tillerson should know how to conduct proper risk management, since ExxonMobil is in the very risky business of oil drilling. In fact, they made their health and safety policies much more conservative after the Exxon Valdez disaster, correctly erring on the side of minimizing the risk of another catastrophic spill. Tillerson would undoubtedly say that we should do what we can to prevent oil spills from happening rather than simply adapting and implementing engineering solutions once they occur. We should apply the same risk management approach to climate change rather than employing Tillerson's newfound cavaleir attitude.

Tillerson then made an increasingly popular argument amongst climate contrarians - that we can simply adapt to climate change.

"And as human beings as a -- as a -- as a species, that's why we're all still here. We have spent our entire existence adapting, OK? So we will adapt to this. Changes to weather patterns that move crop production areas around -- we'll adapt to that. It's an engineering problem, and it has engineering solutions. And so I don't -- the fear factor that people want to throw out there to say we just have to stop this, I do not accept."

It's true that if we had infinite resources, we could probably successfully adapt to the consequences of climate change, to a point. However, in reality we don't have infinite resources, and thus we generally try to utilize those resources most efficiently. When it comes to climate change we have the option to choose our desired combination of mitigation, adaptation, and suffering.

If we so desired, we could shift our agricultural production to wholly different geographic regions. We could move entire cities away from the coastlines. We could change or diets to eat less seafood as marine ecosystems are decimated by ocean acidification. But these sorts of adaptive measures tend to be very expensive, and also tend to be steps people would prefer to avoid.

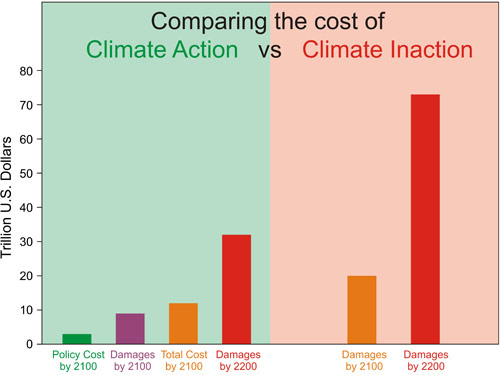

As we recently examined, climate change consequences from carbon emissions are already costing our society hundreds of billions of dollars every year. Research by the German Institute for Economic Research and Watkiss et al. 2005 have concluded that choosing mitigation above adaption would save us tens of trillions of dollars (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Approximate global costs of climate action (green) and inaction (red) in 2100 and 2200. Sources: German Institute for Economic Research and Watkiss et al. 2005

While some climate contrarians have argued that adaption is cheaper than mitigation, they have yet to produce a single economic study to support this assertion. Most frequently they reference (and misrepresent) the work of William Nordhaus, who got sick of these distortions of his research and set the record straight, saying:

"My research shows that there are indeed substantial net benefits from acting now rather than waiting fifty years...the loss from waiting is $4.1 trillion."

In short, while we could adapt to the consequences of climate change to a certain point, as Tillerson argues, that doesn't mean that we should. Listening to Tillerson and choosing adaptation over mitigation would cost us many trillions of dollars.

Like John Christy, Tillerson also argued that poor people in developing countries need fossil fuels.

"There are still hundreds of millions, billions of people living in abject poverty around the world. They need electricity. They need electricity they can count on, that they can afford. They need fuel to cook their food on that's not animal dung. There are more people's health being dramatically affected because they could -- they don't even have access to fossil fuels to burn. They'd love to burn fossil fuels because their quality of life would rise immeasurably, and their quality of health and the health of their children and their future would rise immeasurably. You'd save millions upon millions of lives by making fossil fuels more available to a lot of the part of the world that doesn't have it"

While the poor in developing countries would certainly benefit from increased access to electricity, there is no reason that electricity must come from fossil fuels. Traditionally fossil fuels have come at the cheapest price, but only because they are in effect massively subsidized, because the cost of the climate impacts resulting from their carbon emissions are not reflected in their market price. When we account for all of the costs associated with fossil fuel combustion, they become more expensive than many clean, renewable options.

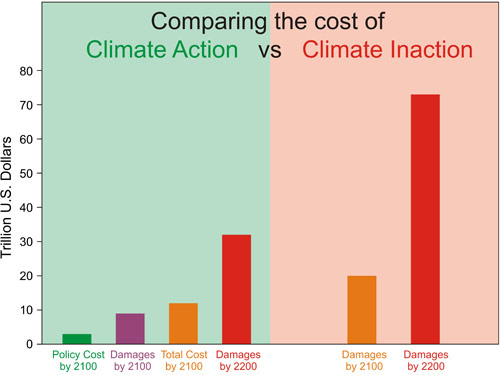

The irony here is that poor developing nations have the fewest resources available to pursue Tillerson's recommended path of adapting to climate change. This is why as Samson et al. (2011) showed, the countries with the lowest CO2 emissions are most vulnerable to and will generally experience the largest climate impacts (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Top Frame - National average per capita CO2 emissions based on OECD/IEA 2006 national CO2 emissions (OECD/IEA, 2008) and UNPD 2006 national population size (UNPD, 2007). Bottom Frame: Global Climate Demography Vulnerability Index. Red corresponds to more vulnerable regions, blue to less vulnerable regions. White areas corresponds to regions with little or no population (Samson et al 2011).

Pay particular attention to Africa, which is generally the region that comes to mind when discussing cooking food with animal dung and having insufficient access to electricity. As the bottom frame of Figure 2 shows, African nations tend to be the most vulnerable to the consequences of climate change, in large part because they lack the resources necessary for adaptation. Tillerson's advocacy for consuming all available fossil fuels and trying to adapt to the consequences is not doing these poor people any favors.

Given that as ExxonMobil CEO, Tillerson's job is to maximize the company's profits, it's not at all surprising that he would downplay the risks associated with consuming his company's products. Since Tillerson is neither a climate scientist nor economist, his opinions on these issues are not particularly credible anyway.

Nevertheless, it is a positive sign that ExxonMobil and climate denial groups like the Cato Institute are moving away from denying that the planet is warming and that humans are causing that warming, and falling back to adaption vs. mitigation arguments. At least this is a step in the right direction, although it still shows that the ExxonMobil climate contrarian tiger has clearly not entirely changed its stripes.

Posted by dana1981 on Friday, 13 July, 2012

|

The Skeptical Science website by Skeptical Science is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. |