How reliable are climate models?

What the science says...

| Select a level... |

Basic

Basic

|

Intermediate

Intermediate

| |||

|

While there are uncertainties with climate models, they successfully reproduce the past and have made predictions that have been subsequently confirmed by observations. |

|||||

Models are unreliable

"[Models] are full of fudge factors that are fitted to the existing climate, so the models more or less agree with the observed data. But there is no reason to believe that the same fudge factors would give the right behaviour in a world with different chemistry, for example in a world with increased CO2 in the atmosphere." (Freeman Dyson)

There are two major questions in climate modeling - can they accurately reproduce the past (hindcasting) and can they successfully predict the future? To answer the first question, here is a summary of the IPCC model results of surface temperature from the 1800s - both with and without man-made forcings. All the models are unable to predict recent warming without taking rising CO2 levels into account. Nobody has created a general circulation model that can explain climate's behavior over the past century without CO2 warming.

Figure 1: Comparison of climate results with observations. (a) represents simulations done with only natural forcings: solar variation and volcanic activity. (b) represents simulations done with anthropogenic forcings: greenhouse gases and sulphate aerosols. (c) was done with both natural and anthropogenic forcings (IPCC).

Predicting/projecting the future

A common argument heard is "scientists can't even predict the weather next week - how can they predict the climate years from now". This betrays a misunderstanding of the difference between weather, which is chaotic and unpredictable, and climate which is weather averaged out over time. While you can't predict with certainty whether a coin will land heads or tails, you can predict the statistical results of a large number of coin tosses. In weather terms, you can't predict the exact route a storm will take but the average temperature and precipitation over the whole region is the same regardless of the route.

There are various difficulties in predicting future climate. The behaviour of the sun is difficult to predict. Short-term disturbances like El Niño or volcanic eruptions are difficult to model. Nevertheless, the major forcings that drive climate are well understood.

A paper led by James Risbey (2014) in Nature Climate Change takes a clever approach to evaluating how accurate climate model temperature predictions have been while getting around the noise caused by natural cycles. The authors used a large set of simulations from 18 different climate models (from CMIP5). They looked at each 15-year period since the 1950s, and compared how accurately each model simulation had represented El Niño and La Niña conditions during those 15 years, using the trends in what's known as the Niño3.4 index.

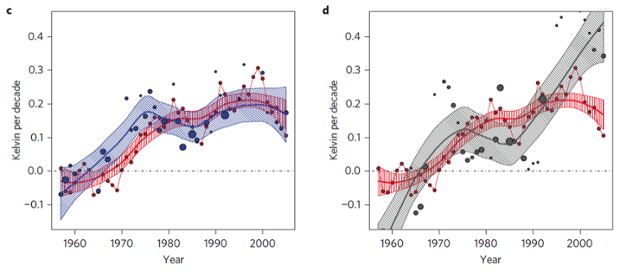

Each individual climate model run has a random representation of these natural ocean cycles, so for every 15-year period, some of those simulations will have accurately represented the actual El Niño conditions just by chance. The study authors compared the simulations that were correctly synchronized with the ocean cycles (blue data in the left frame below) and the most out-of-sync (grey data in the right frame) to the observed global surface temperature changes (red) for each 15-year period.

Figure 2: Red: 15-year observed trends for each period. Blue: 15-year average trends from CMIP5 runs where the model Niño3.4 trend is close to observations. Grey: average 15-year trends for only the models with the worst correspondence to the Niño3.4 trend. The sizes of the dots are proportional to the number of models selected. From Nature Climate Change

Figure 2: Red: 15-year observed trends for each period. Blue: 15-year average trends from CMIP5 runs where the model Niño3.4 trend is close to observations. Grey: average 15-year trends for only the models with the worst correspondence to the Niño3.4 trend. The sizes of the dots are proportional to the number of models selected. From Nature Climate Change

The authors conclude,

When the phase of natural variability is taken into account, the model 15-year warming trends in CMIP5 projections well estimate the observed trends for all 15-year periods over the past half-century.

It's also clear from the grey figure that models that are out-of-sync with the observed changes in these ocean cycles simulate dramatically higher warming trends over the past 30 years. In other words, the model simulations that happened not to accurately represent these ocean cycles were the ones that over-predicted global surface warming.

Climate models have also been accurately projecting global surface temperature changes for over 40 years. Climate contrarians have not:

Figure 3: Various global temperature projections by mainstream climate scientists and models, and by climate contrarians, compared to observations by NASA GISS. Created by Dana Nuccitelli.

A 2019 study led by Zeke Hausfather evaluated 17 global surface temperature projections from climate models in studies published between 1970 and 2007. The authors found "14 out of the 17 model projections indistinguishable from what actually occurred."

Uncertainties in future projections

A common misconception is that climate models are biased towards exaggerating the effects from CO2. It bears mentioning that uncertainty can go either way. In fact, in a climate system with net positive feedback, uncertainty is skewed more towards a stronger climate response (Roe 2007). For this reason, many of the IPCC predictions have subsequently been shown to underestimate the climate response. Satellite and tide-gauge measurements show that sea level rise is accelerating faster than IPCC predictions. The average rate of rise for 1993-2008 as measured from satellite is 3.4 millimetres per year while the IPCC Third Assessment Report (TAR) projected a best estimate of 1.9 millimetres per year for the same period. Observations are tracking along the upper range of IPCC sea level projections.

Figure 4: Observed sea level rise since 1970 from tide gauge data (red) and satellite measurements (blue) compared to model projections for 1990-2010 from the IPCC Third Assessment Report (grey band). (Source: The Copenhagen Diagnosis, 2009)

Similarly, summertime melting of Arctic sea-ice has accelerated far beyond the expectations of climate models. The area of sea-ice melt during 2007-2009 was about 40% greater than the average prediction from IPCC AR4 climate models. The thickness of Arctic sea ice has also been on a steady decline over the last several decades.

Figure 5: Comparison of observed September minimum Arctic sea ice extent through 2008 (red line) with IPCC AR4 model projections. The solid black line shows the mean of the 13 models, and dashed black lines show the range of the model results. The 2009 minimum was calculated at 5.10 million km2, the third lowest year on record and still well below the IPCC worst case scenario. (Source: Copenhagen Diagnosis, 2009)

There's one chart often used to argue to the contrary, but it's got some serious problems, and ignores most of the data.

Do we know enough to act?

Skeptics argue that we should wait till climate models are completely certain before we act on reducing CO2 emissions. If we waited for 100% certainty, we would never act. Models are in a constant state of development to include more processes, rely on fewer approximations and increase their resolution as computer power develops. The complex and non-linear nature of climate means there will always be a process of refinement and improvement. The main point is we now know enough to act. Models have evolved to the point where they successfully predict long-term trends and are now developing the ability to predict more chaotic, short-term changes. Multiple lines of evidence, both modeled and empirical, tell us global temperatures will change 3°C with a doubling of CO2 (Knutti & Hegerl 2008).

Models don't need to be exact in every respect to give us an accurate overall trend and its major effects - and we have that now. If you knew there were a 90% chance you'd be in a car crash, you wouldn't get in the car (or at the very least, you'd wear a seatbelt). The IPCC concludes, with a greater than 90% probability, that humans are causing global warming. To wait for 100% certainty before acting is recklessly irresponsible.

Intermediate rebuttal written by LarryM

Last updated on 29 December 2018 by pattimer. View Archives

Arguments

Arguments

Climate Myth...