Humans aren’t rational. We don’t evaluate facts objectively; instead, we interpret them through our biases, experiences, and backgrounds. What’s more, we’re psychologically motivated to reject or distort information that threatens our identity or worldview – even if it’s scientifically valid. Add to that our modern media landscape where everyone has a different source of “truth” for world events, our ability to understand what is actually true is weaker than ever. How, then, can we combat misinformation when simply presenting the facts is no longer enough – and may even backfire?

In this episode, Nate is joined by John Cook, a researcher who has spent nearly two decades studying science communication and the psychology of misinformation. John shares his journey from creating the education website Skeptical Science in 2007 to his shocking discovery that his well-intentioned debunking efforts might have been counterproductive. He also discusses the “FLICC” framework – a set of five techniques (Fake experts, Logical fallacies, Impossible expectations, Cherry picking, and Conspiracy theories) that cut across all forms of misinformation, from the denial of global heating to vaccine hesitancy, and more. Additionally, John’s research reveals a counterintuitive truth: our tribal identities matter more than our political beliefs in determining what science we accept – yet our aversion to being tricked is bipartisan.

When it comes to reaching a shared understanding of the world, why does every conversation matter – regardless of whether it ends in agreement? When attacks on science have shifted from denying findings to attacking solutions and scientists themselves, are we fighting yesterday’s battle with outdated communication strategies? And while we can’t eliminate motivated reasoning (to which we’re all susceptible), how can we work around it by teaching people to recognize how they’re being misled, rather than just telling them what to believe?

About John Cook

John Cook is a Senior Research Fellow at the Melbourne Centre for Behaviour Change at the University of Melbourne. He is also affiliated with the Center for Climate Change Communication as adjunct faculty. In 2007, he founded Skeptical Science, a website which won the 2011 Australian Museum Eureka Prize for the Advancement of Climate Change Knowledge and 2016 Friend of the Planet Award from the National Center for Science Education. John also created the game Cranky Uncle, combining critical thinking, cartoons, and gamification to build resilience against misinformation, and has worked with organizations such as Facebook, NASA, and UNICEF to develop evidence-based responses to misinformation.

John co-authored the college textbooks Climate Change: Examining the Facts with Weber State University professor Daniel Bedford. He was also a coauthor of the textbook Climate Change Science: A Modern Synthesis and the book Climate Change Denial: Heads in the Sand. Additionally, in 2013, he published a paper analyzing the scientific consensus on climate change that has been highlighted by President Obama and UK Prime Minister David Cameron. He also developed a Massive Open Online Course in 2015 at the University of Queensland on climate science denial, that has received over 40,000 enrollments.

2026 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming News Roundup #10

Posted on 8 March 2026 by BaerbelW, John Hartz, Doug Bostrom

Stories we promoted this week, by category:

Climate Change Impacts (8 articles)

- Humanity heating planet faster than ever before, study finds "Researchers identify sharp rise to about 0.35C every decade, after excluding natural fluctuations such as El Niño" The Guardian, Ajit Niranjan , Feb 6, 2026.

- Dangerous heat for Tour de France riders only a ‘question of time’ "Rising temperatures across France since the mid-1970s are putting Tour de France competitors at 'high risk', according to new research." Carbon Brief, Giuliana Viglione, Feb 24, 2026.

- Wildfire Seasons Are Starting to Overlap. That Spells Trouble for Firefighting. "Simultaneous emergencies in different parts of the world could stop countries from sharing ground crews and equipment, new research warns." The New York Times, Rebecca Dzombak, Feb 27, 2026.

- Will climate change bring more major hurricane landfalls to the U.S.? "A deep dive on the latest hurricane science." Yale Climate Connections, Jeff Masters, Feb 27, 2026.

- Rising carbon dioxide levels are now detectable in human blood earthdotcom, Sanjana Gajbhiye, Mar 1, 2026.

- Wildfires in the far north may be releasing centuries of stored carbon Earthdotcom, Sanjana Gajbhiye, Mar 2, 2026.

- Warming Triggers a Chain Reaction of Disturbance in European Forests "Escalating wildfires, wind damage and insect outbreaks could threaten tourism, water supplies and biodiversity, a new study shows." Inside Climate News, Bob Berwyn, Mar 4, 2026.

- Scientists have been underestimating sea levels — for decades "Our coasts are more vulnerable than we realized."Scientists have been underestimating sea levels — for decades Vox, Umair Irfan, Mar 4, 2026.

Climate Policy and Politics (6 articles)

- Q&A: How Trump is threatening climate science in Earth’s polar regions Carbon Brief, Daisy Dunne, Feb 20, 2026.

- Trump Is Attacking Climate Science. Scientists Are Fighting Back. "It’s easy, looking at the past year, to see the damage the administration has done. But researchers are also stepping up, trying to fill the gaps." The New Republic (TNR), Robert Kopp, Mar 1, 2026.

- Scientists Decry ‘Political Attack’ on Reference Manual for Judges "More than two dozen contributors to the manual criticized the deletion of a chapter on climate science by the Federal Judicial Center" The New York Times, Karen Zraick, Mar 2, 2026.

- OBITUARY: The DOE Climate Working Group Report, 2025-2026 It died in a footnote The Climate Brink, Andrew Dessler, Mar 02, 2026.

- Beyond ‘Endangerment’: Finding a Way Forward for U.S. on Climate "Environmentalists are challenging the EPA’s repeal of the “endangerment finding,” which empowered it to regulate greenhouse gases. Whether or not the action holds up in court, now is the time to develop climate strategies that can be pursued when the political balance shifts." Yale Environment 360, Opinion by Jody Freeman , Mar 3, 2026 .

- As New York Energy Costs Surge, Attention Turns to Landmark Climate Law "The battle to lower costs has reached the State Capitol, where concerns have emerged about the fate of a 2019 climate law and its ambitious goals to reduce greenhouse gas emissions."As New York Energy Costs Surge, Attention Turns to Landmark Climate Law The New York Times, Hilary Howard, Mar 4, 2026.

Skeptical Science New Research for Week #10 2026

Posted on 5 March 2026 by Doug Bostrom, Marc Kodack

Open access notables

Abrupt Gulf Stream path changes are a precursor to a collapse of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, van Westen & Dijkstra, Communications Earth & Environment

The Gulf Stream is part of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC). The AMOC is a tipping element and may collapse under changing forcing. However, the role of the Gulf Stream in such a tipping event is unknown. Here, we investigate the link between the AMOC and Gulf Stream using a high-resolution (0. 1°) stand-alone ocean simulation, in which the AMOC collapses under a slowly-increasing freshwater forcing. AMOC weakening gradually shifts the Gulf Stream near Cape Hatteras northward, followed by an abrupt northward displacement of 219 km within 2 years. This rapid shift occurs a few decades before the simulated AMOC collapse. Satellite altimetry shows a significant (1993–2024, p < 0.05) northward Gulf Stream trend near Cape Hatteras, which is also confirmed in subsurface temperature observations (1965–2024, p < 0.01). These findings provide indirect evidence for present-day AMOC weakening and demonstrate that abrupt Gulf Stream shifts can serve as early warning indicator for AMOC tipping.

High-Resolution Projections of Extreme Heat and Thermal Stress in Southeastern U.S., Lu et al., Weather and Climate Extremes

Considering the increasing frequency, severity, and societal impacts of extreme heat under climate change, understanding the regional dynamics of extreme heat is critical for informing public health preparedness and energy system planning. This study investigates the spatial characteristics, dominant drivers, and future evolution of extreme heat days in North Carolina (NC) and Virginia (VA) using high-resolution simulations from the Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) model based on the Pseudo Global Warming (PGW) method. The analysis of May to September in the two base years, 2010 and 2011, reveals different heat mechanisms. Extreme heats in 2010 are primarily associated with weak synoptic anomalies, whereas the extreme heats in 2011 exhibit stronger land–atmosphere coupling, characterized by soil moisture depletion. Based on these two distinct types of heat mechanisms, projections comparing the current climate (2000-2020) with the late-century period (2060-2089) under three Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSP1-2.6, SSP2-4.5, SSP5-8.5) indicate different increases in daily 2-m maximum temperature ranging from 1.6 °C to over 4.4 °C. These temperature changes are driven by variations in radiative forcing, atmospheric circulation, and land surface conditions. The frequency, duration, and severity of extreme heat days exhibit a nonlinear escalation under the three scenarios. “Danger” and “Extreme Danger” heat days are projected to emerge under SSP5-8.5, underscoring the urgent need for aggressive mitigation and tailored adaptation strategies to reduce thermal stress risks in this region.

Reports from western U.S. firefighters that nighttime fire activity has been increasing during the spans of many of their careers have recently been confirmed by satellite measurements over the 2003–20 period. The hypothesis that increasing nighttime fire activity has been caused by increased nighttime vapor pressure deficit (VPD) is consistent with recent documentation of positive, 40-yr trends in nighttime VPD over the western United States. However, other meteorological conditions such as near-surface wind speed and planetary boundary layer depth also impact fire behavior and exhibit strong diurnal changes that should be expected to help quell nighttime fire activity. This study investigates the extent to which each of these factors has been changing over recent decades and, thereby, may have contributed to the perceived changes in nighttime fire activity. Results quantify the extent to which the summer nighttime distributions of equilibrium dead woody fuel moisture content, planetary boundary layer height, and near-surface wind speed have changed over the western United States based on hourly ERA5 data, considering changes between the most recent decade and the 1980s and 1990s, when many present firefighters began their careers. Changes in the likelihood of experiencing nighttime meteorological conditions in the recent period that would have registered as unusually conducive to fire previously are evaluated considering each variable on its own and in conjunction (simultaneously) with one another. The main objective of this work is to inform further study of the reasons for the observed increases in nighttime fire activity.

Minimizing climate risks will require accelerating the energy transition on all levels and in all sectors. Replacing 1.4 billion fossil with electric road vehicles will, however, be a process spanning multiple decades. Expanding electric bus transit has the potential to reduce the demand for electric cars while needing little additional infrastructure. Yet, accelerating the electrification of public mobility is a challenge in itself. This paper explores the system-wide effect of applying the emerging strategy of e-retrofitting to Europe’s bus fleet. Diesel buses are thereby retrofitted with electric drive-trains, which reduces environmental impacts compared to the production of a new battery-electric bus. This strategy allows to accelerate bus fleet electrification by 15 years and to increase annual transport services by a maximum of 25%, all without the need to prematurely retire functioning buses. Applied across Europe, e-retrofitting buses can save greenhouse gas emissions up to 300 million tons CO, generate jobs, offer business opportunities, reduce raw material demand, and requires minimal additional infrastructure.

ClimarisQ is both a web and mobile game developed by the Institut Pierre-Simon Laplace to support climate change communication through interactive decision-making. This paper presents an exploratory evaluation of the game based on a post-play questionnaire completed by 77 users. Respondents rated ClimarisQ positively in terms of usability and scientific credibility. Self-reported outcomes indicate that the game supported reflection on the complexity, trade-offs, and uncertainty of climate-related decision-making, rather than the acquisition of factual knowledge, particularly among users with prior expertise. The respondent group was predominantly composed of educated and climate-aware adults, which limits generalization to other audiences. Beyond the questionnaire, the game has been tested in dozens of facilitated sessions with thousands of non-specialist participants, with consistently positive feedback. These results suggest that ClimarisQ can function as a complementary tool for climate education and outreach, especially when used in facilitated settings that encourage discussion and interpretation.

The phasing-out of coal-fired power generation is a critical policy imperative in the energy system transition towards climate change mitigation. This research examines whether the public is willing to share the costs that will arise from the phasing-out of coal-fired power generation. To this end, this study analyzes the public's willingness to pay for policies aimed at reducing coal-fired power generation and assesses their economic feasibility. Stated preference data from 1000 Korean households nationwide are analyzed using the contingent valuation method and cost-benefit analysis (CBA). The results indicate that households are willing to pay an average of KRW 4514 (USD 3.45) with a 95% confidence interval of [KRW 4,087, KRW 5017] per month in additional electricity fees for the next five years to implement compensation and support measures for the phasing-out of coal-fired power plants. The results of the CBA, including sensitivity analysis, suggest that the implementation of support and compensation policies for coal power phasing-out may not be economically feasible. The Korean public is not yet fully prepared to bear the costs associated with the phase-out of coal-fired power generation, and either increased electricity tariffs or excessive government investment for this process could provoke considerable controversy.

From this week's government/NGO section:

Takeaways from USA TODAY’s investigation of clean-energy opposition, Bhat et al., USA Today

America’s renewable energy buildout is facing resistance, not just in Washington but in county commission meetings across the country. A growing number of local governments are restricting or outright blocking large-scale wind and solar projects. These restrictions come in the shape of bans, permitting requirements that make projects economically unfeasible or moratoriums that may or may not eventually expire. All the while, changing economics and improved technology have made wind and solar cheaper than natural gas and far cheaper than coal.?The investigation identified at least 755 counties with regulatory mechanisms that render it difficult or impossible to develop large-scale wind or solar projects. The investigation relied on data collected for 3,142 counties covering all 50 states through official announcements, county board meetings, news reports, emails and phone calls to public offices.

Oil spill. How fossil fuel interests are seeping into the voluntary carbon market rulebook, nigo Wyburd and Jonathan Crook, Carbon Market Watch

Despite belonging to the highly polluting fossil fuel sector, major oil and gas companies are not only among the largest buyers of carbon credits, they are also heavily invested in seeking to shape the voluntary carbon market. The authors zoom in this outsized role. They focus on how oil supermajors employ greenwashing strategies, including offsetting their emissions and using carbon credits to give the illusion of meaningful progress towards reaching their climate targets. Driven by a desire to safeguard the supply of cheap and low-quality carbon credits, some fossil fuel companies have also been engaging with policy and governance processes through both formal and informal channels. These fossil fuel interests consistently back approaches that promote carbon credit use that is in alignment with their commercial interests, including expanding the supply of different carbon credit types and continued market growth. In parallel, these companies operate in close proximity to the institutions tasked with defining and safeguarding carbon market integrity, such as the Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market (ICVCM) and the Voluntary Carbon Market Integrity initiative (VCMI). While insufficient information is publicly available to assess whether the outcomes of the work undertaken by voluntary initiatives has been directly influenced by oil and gas companies and other market actors, there are sufficient grounds to consider this a credible risk that warrants serious scrutiny.

93 articles in 45 journals by 477 contributing authors

Physical science of climate change, effects

Abrupt Gulf Stream path changes are a precursor to a collapse of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, van Westen & Dijkstra, Communications Earth & Environment Open Access pdf 10.1038/s43247-026-03309-1

Amplified Mesoscale and Submesoscale Variability and Increased Concentration of Precipitation under Global Warming over Western North America, Guilloteau et al., Journal of Climate Open Access pdf 10.1175/jcli-d-24-0343.1

Will climate change bring more major hurricane landfalls to the U.S.?

Posted on 4 March 2026 by Guest Author

This is a re-post from Yale Climate Connections by Jeff Masters

In brief

- The strongest hurricanes are likely to grow stronger as a result of climate change.

- So far, there has been no significant increase or decrease in the number of major hurricanes making landfall in the United States.

- However, it’s likely that there has been an increase in the number of major hurricanes in the Atlantic as a whole since 1946.

- Also, the intensity of landfalling continental U.S. hurricanes has increased, so even if the total number of landfalls has not increased, their potential to do damage has.

- When major hurricanes do hit, they will do more damage than they did in the past: They will be stronger, wetter, and bring higher storm tides because of sea level rise.

- Expect to see more periods of major U.S. landfall activity in the future, but also gaps when no major landfalls occur.

When I wrote my first-ever blog post on a named storm in the Atlantic on June 9, 2005 — for Tropical Storm Arlene — little did I expect the season of atmospheric mayhem that awaited.

An incredible 28 named storms, 15 hurricanes, and seven major hurricanes later — including four Cat 5s and four U.S. landfalls by major hurricanes — New Year’s Eve 2005 found me blogging on Tropical Storm Zeta a half hour before midnight. I wondered, not for the first time, if climate change had caused us to cross a threshold into a new realm of permanent atmospheric frenzy, since the 2004 hurricane season had also been bonkers.

I asked myself, “Is this going to happen for every Atlantic hurricane season from now on? If so, I’d better get off the computer and go drink some champagne!” And I did.

Fortunately, the 2006 Atlantic hurricane season was an incredible relief — below average in all metrics, with no landfalling hurricanes anywhere in the Atlantic. And remarkably, for the next 11 years, no major hurricanes hit the U.S. — the longest such gap on record (Fig. 1). Perhaps more unbelievable: No hurricanes of any kind hit Florida from 2006-2015 — a 10-year landfall drought.

Figure 1. Landfalling mainland U.S. Category 3, 4, and 5 hurricanes since 1900. The blue trend line shows no significant trend.

Figure 1. Landfalling mainland U.S. Category 3, 4, and 5 hurricanes since 1900. The blue trend line shows no significant trend.

Just have a Think - The Primary Energy Fallacy finally laid to rest!

Posted on 3 March 2026 by Guest Author

This video includes personal musings and conclusions of the creator Dave Borlace. It is presented to our readers as an informed perspective. Please see video description for references (if any).

Video description

Why does the global energy transition look so slow in the headline statistics — even as solar, wind, EVs and heat pumps surge ahead? New analysis from EMBER argues the problem isn’t the transition — it’s the way we’ve been counting it. By shifting the focus from “primary energy” to “useful energy” the paper reveals how electrification dramatically reduces wasted energy and why renewables are far more competitive than traditional charts suggest.

Support Dave Borlace and his "Just have a Think" channel on patreon: https://www.patreon.com/cw/justhaveathink

The AI-Augmented Scientist

Posted on 2 March 2026 by Zeke Hausfather

This is a re-post from The Climate Brink

I was reminded of Arthur C. Clark’s famous third law the other day, that “any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” I’d recently gotten Claude Code set up on my computer, and was using it to help write the code for some reduced-complexity climate model runs. Suddenly projects that would have taken hours or even days were running in minutes. It was not perfect – I needed to carefully help it create project plans, develop tests, and review the results – but it represented a remarkable step up from the capabilities I was familiar with in past web-based LLM interfaces.

I’m something of an unusual climate scientist as, rather than working in academia, my main role is as the climate research lead at Stripe, a financial technology company in Silicon Valley. As such, I’ve probably used AI far more than most other folks in the scientific community, given that we are strongly encouraged to use it extensively for work. I’ve also worked directly with AI labs on projects to evaluate the performance of LLMs in answering climate science questions, and to help enable AI tools to support scientific collaboration.

I started using GPT3.5 back in 2022 when it first came out. Initially it was a novelty but not particularly useful for scientific applications. It was quite prone to hallucinations, would get into endless spirals of errors it would then try and fix, and would often grossly misinterpret instructions. But it had decent skill at coding, and could (sometimes) help solve bugs in my code much faster than trying to search Stack Overflow or old Reddit posts.

This changed with the release of GPT4 in 2023, and particularly with the release of Code Interpreter that could automate data analysis and visualization capabilities. It still hallucinated, was not great at writing, but could arguably code better than the typical scientist. One of the earlier projects I did was to ask it to help visualize how unusual the summer of 2023 was in terms of global temperatures, which helped generate both the ideas of and code for this somewhat viral Climate Brink post (which I referred to as “gobsmackingly bananas” at the time).

Today the tools are much better than they were in 2023. Hallucinations still exist, but they are much less frequent. As someone who has used these tools more than most in the scientific community, I have a good sense of what they work for and what they do not do well today. The tools I primarily use now are Claude Code (Opus 4.6, via my terminal) and the web-app for Gemini (3.1) for projects where integration with my email, Drive, and other parts of the Google ecosystem is helpful.

2026 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming News Roundup #09

Posted on 1 March 2026 by BaerbelW, John Hartz, Doug Bostrom

Stories we promoted this week, by category:

Climate Policy and Politics (13 articles)

- States push climate superfund bills despite Trump’s opposition "The legislation would make oil and gas firms pay for climate damages from burning their products. Trump has referred to such laws as 'extortion'.” Canary Media, Sarah Shemkus, Feb 17, 2026.

- Data Centers Are Not a License to Drill Union of Concerned Scientists, Laura Peterson, Feb 18, 2026.

- Why rejecting the endangerment finding also rejects climate science Chemical & Engineering News, Leigh Krietsch Boerner, Feb 18, 2026.

- The reckless repeal of the Endangerment Finding Union of Concerned Scientists, Opinion by John Holden , Feb 19, 2026.

- ‘Irreversible on any human timescale’: Scientist revea‘Irreversible on any human timescale’: Scientist reveals best and worst-case scenario for Antarcticals best and worst-case scenario for Antarctica "Despite being far away from civilisation, a melting Antarctic’s "disastrous" consequences will ripple across the world, researchers warn." euronews.com, Liam Gilliver, Feb 20, 2026.

- Trump is making coal plants even dirtier as AI demands more energy "The US is lowering its standards for power plant pollution while generative AI and the Trump administration revive old coal plants." The Verge, Justine Calma, Feb 20, 2026.

- Health and Climate Consequences of EPA’s Endangerment Finding Repeal ‘Cannot Be Overstated’Interview by Jenni Doering "In short: the agency will no longer be able to regulate carbon pollution or greenhouse gases—though a couple of scenarios might prevent President Trump from getting his way." Inside Climate News, Interview by Jenni Doering, Feb 21, 2026.

- Under water, in denial: is Europe drowning out the climate crisis? "Even as weather extremes worsen, the voices calling for the rolling back of environmental rules have grown louder and more influential" The Guardian, Ajit Niranjan, Feb 21, 2026.

- Why the endangerment finding mattered so much for health and the climate Harvard School of Public Health, Karen Feldscher, Feb 24, 2026.

- China cashes in on clean energy as Trump clings to coal "The Trump administration has rolled back environmental protections and blocked green energy development, China is forging ahead." Deutsche Welle (DW), Sarah Steffen, Feb 24, 2026.

- Here’s a reality check on Trump’s AI pledge "Trump’s promise to protect power customers’ wallets from data centers covers only part of the costs of expanding AI." Politico, Zack Coleman & Peter Behr, Feb 25, 2026.

- Trump touts ‘drill, baby, drill’ agenda – but no mention of climate crisis "President derided Biden’s ‘green new scam’ during State of the Union address, and hailed the rise in US oil production" The Guardian, Analysis by Dharna Noor, Feb 25, 2026.

- Trump is dismantling climate rules. Industry is worried. Brookings, Commentary by Samantha Gross & Ryan Beane, Brookings, Feb 26, 2026, Aug 26, 2026.

Skeptical Science New Research for Week #9 2026

Posted on 26 February 2026 by Doug Bostrom, Marc Kodack

Open access notables

Relative Vulnerability of US National Parks to Cumulative and Transformational Climate Impacts, Michalak et al., Conservation Letters

National Parks are under threat from multiple interacting climatic changes, which have already triggered transformations in these protected landscapes. We conducted a multidimensional analysis of climate-change vulnerability for National Parks to identify which parks are most at risk of climate-change impacts and therefore in the greatest need of targeted climate-change vulnerability assessment and planning. We identified 174 (67%) parks as most exposed to one or more potentially transformative climate impacts including fire, drought, sea-level rise, and forest pests and diseases. Cumulative vulnerability across multiple dimensions was the highest for parks in the Midwest and eastern United States due to high physical exposures, the exacerbation of existing stressors, and high surrounding land-use intensity. Western parks exhibited lower cumulative vulnerability due to less intense land use and topography that may provide climatic refugia. However, western parks tended to be most exposed to multiple transformative impacts. These widespread, diverse threats highlight not only the need for coordinated evaluation of vulnerabilities from multiple perspectives, but also the need for park managers to evaluate and plan for potentially irreversible ecological changes to the landscapes and resources that parks are intended to preserve.

[At time of publication the US executive branch has acted to censor access to previously available information about climate change for park visitors.]

Increasing synchronicity of global extreme fire weather, Yin et al., Science Advances

Concurrent extreme fire weather creates favorable conditions for widespread large fires, which can complicate the coordination of fire suppression resources and degrade regional air quality. Here, we examine the patterns and trends of intra- and interregional synchronous fire weather (SFW) and explore their links to climate variability and air quality impacts. We find climatologically elevated intraregional SFW in boreal regions, as well as interregional synchronicity among northern temperate and boreal regions. Significant increases in SFW occurred during 1979 to 2024, with more than a twofold increase observed in most regions. We estimate that over half of the observed increase is attributable to anthropogenic climate change. Internal modes of climate variability strongly influence SFW in several regions, including Equatorial Asia, which experiences 43 additional intraregional SFW days during El Niño years. Furthermore, SFW is strongly correlated with regional fire-sourced PM2.5 in multiple regions globally. These findings highlight the growing challenges posed by SFW for firefighting coordination and human health.

Coastlines retreat tipping point under storm climate changes, Aparicio et al., Scientific Reports

Projected changes in ocean–atmosphere coupling under global warming suggest an intensification of storm climates, which, combined with sea-level rise, poses profound challenges to the resilience of sandy shorelines. Therefore, the definition of relevant indicators assessing beach response regimes to wave climate is crucial for future forecasts Here, we analyze 23 years of satellite-derived shoreline positions together with offshore wave data to quantify storm-induced erosion and post-storm recovery tendencies at synoptic scales. Our approach integrates statistically robust storm composites, compared against in situ observations from six sites worldwide, and demonstrates that daily storm-induced shoreline dynamics can be inferred from monthly global shoreline datasets. By extending the analysis using 60-year of wave reanalysis, we identify a critical threshold beyond which shoreline evolution shifts from a seasonal to a storm-dominated regime, leading to persistent erosion trajectories. Since the late 1950s, the proportion of storm-dominated beaches has increased by 2% globally, with pronounced hot-spots emerging. While local beach morphology remain essential to fully resolve coastal dynamics, our findings reveal coherent large-scale tendencies that complement site-specific surveys and provide a global framework to guide targeted field efforts. These results highlight the pivotal role of storm regime shifts in shaping the future evolution of sandy shorelines.

Deliberate destabilization on trial: Fair-process lessons from the Czech Coal Commission, ?ernoch et al., Energy Research & Social Science

Expert commissions have become pivotal in coal-phase-out governance, yet their capacity to unsettle incumbent coal regimes remains contested: do they genuinely shift entrenched power relations or merely create an illusion of participatory legitimacy? Drawing on energy-justice and transition studies, this article approaches the issue from the perspective of procedural justice and assumes this tenet of justice is crucial in shaping the outcome of an institutionally induced destabilization. We develop a four-part framework of procedural justice – member selection, stakeholder balance, deliberative conditions, and public transparency – and apply this framework to the Czech Coal Commission (2019–2021), which was established as an expert body tasked with establishing the coal phase-out schedule. Our results show that the Czech Coal Commission was blatantly procedurally unjust. Discretionary appointments, industry-leaning membership, and compressed timelines that circumscribed substantive deliberation ultimately enabled coal incumbents to retain power over the outcome. This case underscores that rigorous procedural design is a necessary precondition for commissions to function as effective agents of destabilization within fossil-fuel regimes, and that design choices must be addressed if similar bodies are to support credible and socially legitimate coal exits.

From this week's government/NGO section:

Nearly half of Americans think they'll see catastrophic impacts of climate change in their lifetimes, Alexander Rossell Hayes, Economist/YouGov

A majority (59%) of Americans believe that the world's climate is changing as a result of human activity. A further 22% say the climate is changing but not because of human activity. Only 6% say the climate is not changing Nearly half (45%) of Americans think they will see catastrophic impacts of climate change in their lifetimes. About one-third (31%) do not think they will see catastrophic effects, with the remaining 24% not sure A majority (57%) of Americans say the U.S. should do more to address climate change. Only 16% say that the U.S. should do less Most Democrats (90%) and a majority (58%) of Independents say the U.S. should do more to address climate change. Republicans are more divided: 25% say the U.S. should do more, 29% say it should not change what it's doing, and 33% say it should do less Younger adults are more likely than older Americans to say the U.S. should do more to address climate change.

Global Warming’s Six Americas, Fall 2025, Leiserowitz et al., Yale University and George Mason University

In 2009, the authors identified Global Warming’s Six Americas – the Alarmed, Concerned, Cautious, Disengaged, Doubtful, and Dismissive – six distinct audiences within the American public. The Fall 2025 Climate Change in the American Mind survey finds that 25% of Americans are Alarmed and that the Alarmed outnumber the Dismissive (11%) by a ratio of more than 2 to 1. Further, when the Alarmed and Concerned are grouped together, about half of Americans (52%) fall into one of these audiences. Overall, Americans are more than twice as likely to be Alarmed or Concerned than they are Doubtful or Dismissive (24%).

99 articles in 56 journals by 670 contributing authors

Physical science of climate change, effects

Coastlines retreat tipping point under storm climate changes, Aparicio et al., Scientific Reports Open Access pdf 10.1038/s41598-026-40886-9

Ecological Feedbacks in the Earth System, Donges et al., Earth System Dynamics Open Access pdf 10.5194/esd-12-1115-2021

Fossil fuel pollution’s effect on oceans comes with huge costs

Posted on 25 February 2026 by dana1981

This is a re-post from Yale Climate Connections

Florida’s barrier reef is in trouble – and it’s costing us.

The reef has been experiencing a severe outbreak of stony coral tissue loss disease over the past decade. The likely cause: stress from the warming climate and acidifying waters, both the result of burning fossil fuels.

The financial stake of losing the reef is high. Florida’s coral reefs are estimated to draw in over $1 billion in tourism revenue each year, provide $650 million in flood protection benefits, and support over 70,000 jobs. What’s more, coral reefs protect people and property by dissipating up to 97% of wave energy, lessening storm surges.

A new study in Nature Climate Change looks at such costs worldwide, estimating the total price of climate-change-related damage to the world’s oceans. The study concludes that accounting for ocean impacts nearly doubles the estimated climate costs to society, known as the social cost of carbon.

But as with most climate impacts, these costs are unequally borne, most heavily by people in poorer island nations and in other coastal regions like Florida. And as with all climate threats, they are being wholly ignored by the Trump administration.

‘A missing piece’

Earth’s oceans play a critical and often overlooked role in the health and well-being of people and cultures around the world. The average person consumes nearly one pound of seafood per week, which provides important dietary nutrients. Coastal ecosystems like mangrove forests and coral reefs also protect coastal communities against storm surges, a growing threat as a result of rising sea levels and climate-intensified storms.

But these benefits, which are threatened by climate change, are difficult to quantify. And when they’re not quantified, they’re left out of experts’ estimates of the damages we incur by burning fossil fuels and releasing climate-warming carbon dioxide – the social cost of carbon.

As a result, even when the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency updated the federal estimate of the social cost of carbon in 2023 to nearly four times its previous value, the agency noted that this was likely still an “underestimate [of] the damages associated with increased climate risk.”

Climate impacts in the oceans in particular have been “a big missing piece recognized by every major assessment” of the social cost of carbon, said Bernie Bastien-Olvera, a climate scientist at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, in an email. He is the lead author of the new Nature Climate Change study.

Fact brief - Do solar panels work in cold or cloudy climates?

Posted on 24 February 2026 by Sue Bin Park

![]() Skeptical Science is partnering with Gigafact to produce fact briefs — bite-sized fact checks of trending claims. You can submit claims you think need checking via the tipline.

Skeptical Science is partnering with Gigafact to produce fact briefs — bite-sized fact checks of trending claims. You can submit claims you think need checking via the tipline.

Do solar panels work in cold or cloudy climates?

Solar panels still generate electricity on cloudy days and in cold weather, albeit less.

Solar panels still generate electricity on cloudy days and in cold weather, albeit less.

Clouds cut output as less sunlight reaches the panels, but they continue producing power from indirect light. Snow cover can temporarily block light, though it is typically not obstructed by thin layers of snow. Additionally, most solar panels in the U.S. run more efficiently in cooler weather, as heat lowers performance.

Winter generation can be lower due to shorter days, notably at middle latitudes; cities like Denver receive nearly three times more solar energy in June than December. This mainly affects what share of a home’s electricity solar covers, especially where heating raises demand. Average winter electricity use of U.S. homes is estimated to be six times that of summer use.

Despite seasonal dips, solar still displaces fossil fuel electricity over the year, delivering large net emissions reductions across a panel’s multi-decade lifespan.

Go to full rebuttal on Skeptical Science or to the fact brief on Gigafact

This fact brief is responsive to quotes such as this one.

Sources

Renewable Energy Journal On the investigation of photovoltaic output power reduction due to dust accumulation and weather conditions

Renewable Energy Journal Temperature and thermal annealing effects on different photovoltaic technologies

ACS Omega Journal Comprehensive Analysis of Solar Panel Performance and Correlations with Meteorological ParametersC

SEIA What happens to solar panels when it’s cloudy or raining?

US Department of Energy Solar Photovoltaics Supply Chain Deep Dive Assessment

US Department of Energy Let it Snow: How Solar Panels Can Thrive in Winter Weather

Columbia Law School Sabin Center for Climate Change Law Rebutting 33 False Claims About Solar, Wind, and Electric Vehicles

Please use this form to provide feedback about this fact brief. This will help us to better gauge its impact and usability. Thank you!

After a major blow to U.S. climate regulations, what comes next?

Posted on 23 February 2026 by dana1981

This is a re-post from Yale Climate Connections. Watch the video accompanying this transcript here

As I wrote back in August when the EPA released its draft proposal, the agency has now – over a decade and a half later – reinterpreted the Clean Air Act to only apply to direct health impacts from local pollution, and not to indirect health effects, like those associated with global climate pollutants.

The agency finalized the decision six months later. And the EPA has already been rolling back all of its climate regulations.

It’s worth bearing in mind that while EPA regulations could be effective at reducing climate pollution, in practice, they haven’t done a whole lot. That’s because EPA regulations tend to swing back and forth every time a new political party takes control of the White House.

Vehicle tailpipe standards are the only significant climate-related regulation that’s gone into effect, and even those overlapped with separate vehicle fuel efficiency standards – which are also now being rolled back. Overall, nearly all of the United States’ emissions reductions have come from the power sector, but that’s because cleaner sources of electricity became cheaper than coal, not because of EPA regulations.

What’s next?

So what happens next is that various groups will sue the EPA, and the case will ultimately be appealed up to the Supreme Court in a process that will likely take several years. At that point, there will be three possible outcomes.

In a best-case scenario, the Supreme Court could rule that the EPA is wrong and must regulate climate pollution under the Clean Air Act. That would require the agency to reissue a broad swath of climate pollutant regulations in the ensuing years.

In a middle scenario, they could narrowly rule in favor of the EPA, giving the agency the discretion to decide whether to regulate climate pollutants. That would maintain the status quo of regulatory swings whenever a new party wins control of the White House.

In the worst-case scenario, the Supreme Court could rule that the EPA is correct in its interpretation that the agency doesn’t have the authority to regulate climate pollutants under the Clean Air Act. That would tie future administrations’ hands on climate regulations. That could also leave fossil fuel companies liable to state-level lawsuits. They were shielded from those by the existence of federal climate regulations.

In that case, or at least in the meantime, that leaves American climate policy almost exclusively in the hands of Congress and individual states.

2026 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming News Roundup #08

Posted on 22 February 2026 by BaerbelW, John Hartz, Doug Bostrom

Stories we promoted this week, by category:

Climate Policy and Politics (17 articles)

- Democratic senators launch inquiry into EPA’s repeal of key air pollution enforcement measure "Senators said repeal was ‘particularly troubling’ and was counter to EPA’s mandate to protect human health" The Guardian, Marina Dunbar, Feb 10, 2026.

- What repealing the ‘endangerment finding’ means for public health "The EPA has scrapped a rule stating that climate change harms human health. Here’s what that could mean" Scientific American, Andrea Thompson, Feb 12, 2026.

- Trump Administration Dropped Controversial Climate Report From Its Decision to Rescind EPA Endangerment Finding "The final EPA rule explicitly omitted the report commissioned last year to justify revoking the endangerment finding, citing 'concerns raised by some commenters'.” Inside Climage News, Dennis Pillion, Feb 13, 2026.

- The First Casualty of Trump’s Climate Action Repeal: The U.S. EV Transition "Tailpipe standards meant to hasten adoption of electric vehicles were slashed alongside the scientific basis for regulating greenhouse gas emissions. That will come at a cost." Inside Climate News, Marianne Lavelle & Dan Gearino, Feb 13, 2026.

- Six possible effects of Trump's climate policy change BBC News, Michael Sheils McNamee, Feb 13, 2026.

- Trump Tracker: Why we're keeping count of every climate attack the POTUS unleashes in 2026 "Euronews Green is holding the world's most powerful man to account, by documenting all the ways he's sabotaging climate progress this year." AP/Euronews, Liam Gilliver , Feb 13, 2026.

- Opinion: Why Aren’t We More Alarmed by the Coming Climate Crisis? Vanguard News, Opinion by David Greenwald, Feb 14, 2026.

- Trump touts climate savings but new rule set to push up US prices "Critics accuse administration of ‘cooking the books’ by claiming US would save $1.3tn from climate finding reversal" The Guardian, Analysis by Dharna Noor, Feb 15, 2026.

- Q&A: What does Trump’s repeal of US ‘endangerment finding’ mean for climate action? Carbon Brief, Multiple Authors, Feb 16, 2026.

- After a major blow to U.S. climate regulations, what comes next? "Dana Nuccitelli explains in two minutes and 22 seconds." Yale Climate Connections, Dana Nuccitelli, Feb 16, 2026.

- Big Tech’s ‘AI Climate Hoax’: Study Shows 74% of Industry’s Claims Unproven “Tech companies are using vagueness about what happens within energy-hogging data centers to greenwash a planet-wrecking expansion.” Common Dreams, Brad Reed, Feb 17, 2026.

- Public health and green groups sue EPA over repeal of rule supporting climate protections AP News, Matthew Daly, Feb 18, 2026.

- E.P.A. Faces First Lawsuit Over Its Killing of Major Climate Rule "Environmental and health groups sued the E.P.A. over its elimination of the endangerment finding. The matter is likely to end up before the Supreme Court." The New York Times, By Karen Zraick, Feb 18, 2026.

- Environmental protest group says FBI is investigating it for terrorism "Extinction Rebellion says some members have been visited by agents claiming to be FBI amid Trump’s threats toward liberal groups" The Guardian, Reuters, Feb 18, 2026.

- US succeeds in erasing climate from global energy body’s priorities "Trump’s energy chief had threatened to leave the International Energy Agency if it continued to focus on climate." Politico, Elena Giordano, Feb 19, 2026.

- Trump’s Move to Demolish Demolish Greenhouse Gas Standards Is Based on a Lie Slate, Richard L. Revesz, Feb 20, 2026.

- The Climate Won’t Bend To Trump’s Will To Power "The danger of cancelling the 'endangerment' finding."https://www.noemamag.com/the-climate-wont-bend-to-trumps-will-to-power/ Noema Magazine, Nathan Gardels, Feb 20, 2026.

Skeptical Science New Research for Week #8 2026

Posted on 19 February 2026 by Doug Bostrom, Marc Kodack

Open access notables

Inoculation theory as a design approach to game-based misinformation interventions: a review, Henderson & Pallett, Popular Communication

Inoculation theory as a design approach to game-based misinformation interventions: a review, Henderson & Pallett, Popular Communication

Misinformation has been demonstrated to pose a great risk to society, demanding action from policymakers and educators. Inoculation theory is a theory of resistance to influence, which in recent years has been a foundational theory for game-based interventions against misinformation. While many game-based interventions have been found to be efficacious, there is a lack of understanding of the underlying mechanisms which make them work. This review critically engages with the current state of game-based misinformation interventions, identifies gaps in game design and research, and investigates the relationship between inoculation theory and game design. We find that homogeneity in design has left some areas of game design underexplored, and discussion surrounding game design decisions—particularly the integration of inoculation theory components—is often superficial. We call for further research understanding the efficacy of different game designs and design processes, and more discussion of how inoculation mechanisms can be stimulated in game-based contexts.

Human-induced climate change amplification on storm dynamics in Valencia’s 2024 catastrophic flash flood, Calvo-Sancho et al., Nature Communications

In October 2024, Valencia (Spain) experienced rainfall accumulations in a few hours surpassing annual averages (771.8 mm in 16 h in the official weather station at Turís) and breaking the record for one hour rainfall accumulation in Spain (184.6 mm), resulting in 230 fatalities. Here, we present a physical-based attribution study employing a km-scale pseudo-global warming storyline approach to assess the contribution of anthropogenic climate change. We show that present-day conditions led to a 20% °C?¹ increase in 1-hour rainfall intensity, exceeding Clausius-Clapeyron scaling. This intensification was driven by enhanced atmospheric moisture from warmer sea surface temperatures, leading to increased convective available potential energy, stronger updrafts, and microphysical changes including elevated graupel concentrations. These results demonstrate that anthropogenic climate change could intensify the occurrence of flash-floods in the Western Mediterranean region: in this particular case, it intensified the 6-h rainfall rate by 21%, amplified the area with total rainfall above 180 mm by 55%, and increased the volume of total rain within the Jucar River catchment by 19% compared to the pre-industrial era.

A chilling effect in a warming world: how the threat of SLAPPs shapes climate law, Arvan, Environmental Politics

Strategic lawsuits against public participation (SLAPPs) are meritless cases filed by powerful actors seeking to silence their critics through costly, protracted litigation. As climate change litigation (CCL) against corporations has surged since the Paris Agreement, so too has the threat of retaliatory SLAPPs against climate activists. In the US, activists must weigh the threat of being entangled in a resource-depleting SLAPP in decisions around whether, and where, to file strategic CCL. SLAPPs so burden the courts and contravene democratic values that 35 states and the District of Columbia have laws attempting to restrict them. How does spatial and temporal variation in legal protections afforded by state anti-SLAPP laws affect activists’ willingness to sue corporations over climate change? Analyzing CCL caseloads in American courts between 2015 and 2024, I find jurisdictions with anti-SLAPP protections attract corporate CCL, indicating that legislative action on free speech helps shape the development of climate law.

Comparing two court rulings on Shell's carbon emissions with climate-policy science, van den Bergh & van Soest, Energy Research & Social Science

In November 2024, a ruling by a Dutch Court of Appeal overturned a 2021 District Court verdict concerning the obligations of the oil and gas company Shell to reduce its carbon emissions. This perspective article examines the scientific basis of the differing arguments in the two court rulings, with a particular focus on the effectiveness of emissions-reduction strategies. To this end, we first summarize the reasoning in both rulings and identify their key points of divergence. Subsequently, we assess which ruling aligns more closely with the scientific literature on climate policy. Our analysis zooms in on four issues: the public-good nature of climate mitigation and the problem of free-riding; the aim and impact of the European Union's Emissions Trading System; the treatment of Scope 3 emissions generated by end users of Shell's products; and the roles of companies versus the state in achieving emissions reductions. We conclude that the Court of Appeal's ruling is more consistent with current scientific insights about effective climate policy than the earlier District Court decision. This is not to deny that companies like Shell will have to fundamentally transform – or otherwise eventually disappear – on the path to a zero?carbon economy. But such change is most likely to occur as the outcome of a systemic policy approach that delivers steady and substantial emissions reductions across all sectors and jurisdictions. We therefore argue that a more effective legal strategy is to pursue legal action against governments that fail to implement policies in line with internationally agreed climate targets.

From this week's government/NGO section:

A climate of insecurity. Climate change and organized crime in cities, Antônio Sampaio, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime

The author examines the intersection of climate change and organized crime in cities. The relationship between these issues is a critical area for policy and programming in governments and multilateral organizations. There is already significant evidence of the central role that cities play as destinations for climate-affected migrants fleeing both rapid- and slow-onset disruptions to their rural livelihoods or moving within cities affected by sea level rises, increased flooding or heat islands. Urbanization is not necessarily a negative or crime-inducing trend, but the rapid movement of people to areas unprepared to cope with service provision and law enforcement demands, coupled with increased pressures on resources such as water and land, can provide opportunities for criminal groups to profit through exploitative, predatory and violent practices. Three such areas require policy and expert attention: human trafficking and modern slavery affecting rural-to-urban migrants; organized crime involvement in water provision in cities; and corruption and the operation of mafia-style groups in urban land and housing.

When Home Becomes Uninhabitable. Planned Relocations as a Global Challenge in the Era of Climate Change, Nadine Knapp, Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik

With climate change advancing, the planned relocation of entire communities from risk areas is becoming unavoidable. It is already a reality worldwide and will become increasingly necessary in the future as a measure of climate adaptation and disaster risk reduction. Relocation can save lives and reduce the risk of displacement. Nevertheless, this measure is considered a “last resort” because it is expensive, deeply affects livelihoods, social networks and cultural identities, and carries new risks. To be effective, it must be participatory, human rights-based, and accompanied by development-oriented measures that strengthen the well-being and resilience of those affected and reduce structural inequalities. Many places lack the political will, concrete strategies and resources for this – especially in low-income countries with already limited adaptation capacities. These countries are therefore heavily dependent on international support, which has mostly been fragmented, ad hoc and uncoordinated.

125 articles in 45 journals by 823 contributing authors

Physical science of climate change, effects

Characterising marine heatwaves in the Svalbard Archipelago and surrounding seas, Williams-Kerslake et al., Open Access 10.5194/egusphere-2025-4269

Dynamic and Thermodynamic Contributions to Future Extreme-Rainfall Intensification: A Case Study for Belgium, Schoofs et al., International Journal of Climatology 10.1002/joc.70192

End-of-Twenty-First-Century Changes on the Antarctic Continental Shelf under Mid- and High-Range Emissions Scenarios, Dawson et al., Journal of Climate 10.1175/jcli-d-24-0189.1

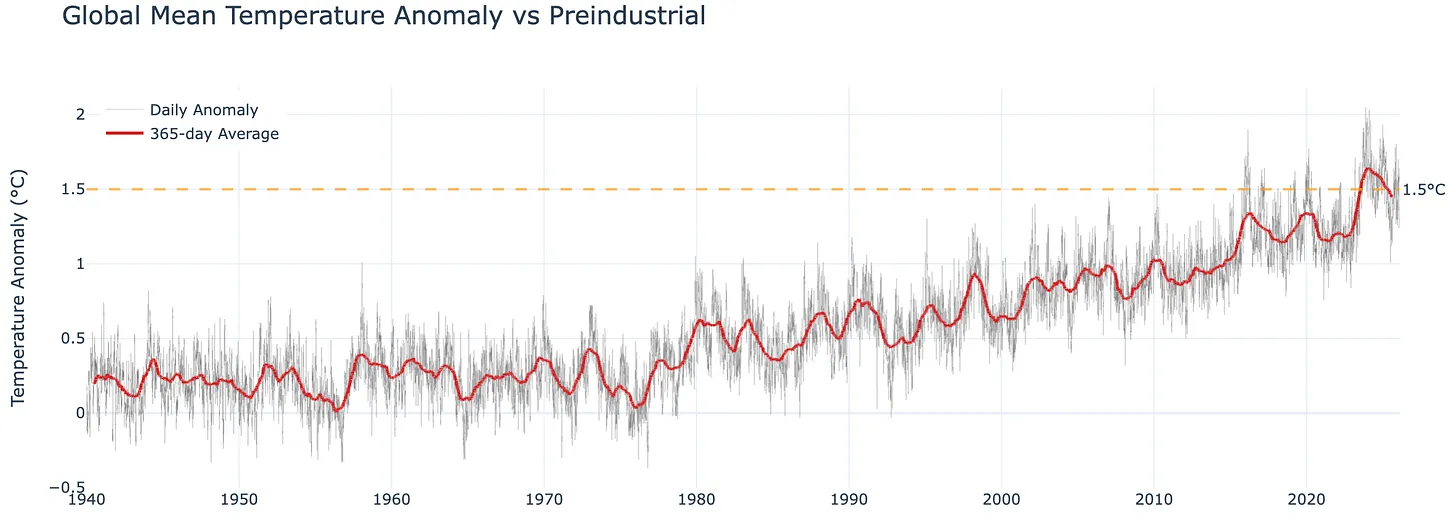

Introducing the Climate Brink Dashboard

Posted on 18 February 2026 by Zeke Hausfather

This is a re-post from The Climate Brink

With the advent of modern reanalysis products (weather models run backwards in time, ingesting data from satellites, weather balloons, airplanes, and surface observations) we now have an unprecedented look at the real-time evolution of the Earth’s climate.

I often use ECMWF’s ERA5 reanalysis (which is arguably the most state-of-the-art of the bunch) to look at current daily global temperature anomalies, to forecast where the current month might end up, or to use as inputs to a model (along with El Nino / La Nina predictions) to estimate what temperatures for the year will be.

But rather than manually making these charts every week or so, I (admittedly with the help of Claude Code) have put together an interactive climate dashboard that will live here at The Climate Brink: https://dashboard.theclimatebrink.com/

It currently includes interactive graphics for daily surface temperatures (you can mouse over each day to see the anomaly, and drag your curser to zoom in on any particular period of interest).

Climate Adam - Climate Scientist Reacts to AI Overlords

Posted on 17 February 2026 by Guest Author

This video includes personal musings and conclusions of the creator and climate scientist Dr. Adam Levy. It is presented to our readers as an informed perspective. Please see video description for references (if any).

Video description

Artificial Intelligence is here, and it's changing the world. But when it comes to climate change, whether those AI changes are going to save us or doom us depends heavily on who you ask. I take a look at what our AI Overlord CEOs have been saying about climate change, and about AI's huge energy needs. And see just how much they contradict each other and themselves - especially when it comes to the vast amounts of energy our AI future (might) need, and the climate change consequences this would cause. Featuring Sam Altman, Bill Gates, Mark Zuckerberg, Elon Musk, Eric Schmidt, and Sundar Pichai.

Support ClimateAdam on patreon: https://patreon.com/climateadam

[youtube error="Video ID parse error."]

Trump just torched the basis for federal climate regulations. Here’s what it means.

Posted on 16 February 2026 by Guest Author

This is a re-post from Yale Climate Connections by Sara Peach

The Trump administration on Thursday revoked the basis for federal climate regulations, undermining the Environmental Protection Agency’s ability to protect the environment and public health.

Here’s what every U.S. resident should know about what just happened.

The EPA determined in 2009 that climate pollution endangers public health and welfare.

Mainstream, peer-reviewed scientific research shows that climate-warming greenhouse gases are increasing the number of extreme heat waves, severe storms, and other dangerous weather events.

Under former President Barack Obama, the EPA reviewed the evidence, and the agency’s “scientific conclusion, known as the endangerment finding, determined that greenhouse gases threaten public health and welfare,” The New York Times reports. “It required the federal government to regulate these gases, which result from the burning of oil, gas and coal.”

Among scientists, that perspective has not changed. Just the opposite: “The scientific understanding of human-driven climate change is much stronger today than it was in 2009 when the EPA first issued the endangerment finding,” climate scientist Zeke Hausfather wrote on Bluesky. “There is no scientific basis for the Trump administration’s decision to repeal it.”

The Trump administration is revoking standards for the two biggest sources of U.S. climate pollution.

Together, transportation and electric power plants generate over half the country’s climate-warming emissions.

Administration officials told the Wall Street Journal this week that they would revoke climate emissions standards for motor vehicles. Separately, the administration is working to gut or repeal standards for power plants, Mother Jones reports.

2026 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming News Roundup #07

Posted on 15 February 2026 by BaerbelW, John Hartz, Doug Bostrom

Stories we promoted this week, by category:

Climate Policy and Politics (10 articles)

- After Republican complaints, judicial body pulls climate advice "Meant to help judges handle scientific issues, document is now climate-free." Ars Techica, John Timmer, Feb 10, 2026.

- The E.P.A. Is Barreling Toward a Supreme Court Climate Showdown "The agency is racing to repeal a scientific finding that requires it to fight global warming. Experts say the goal is to get the matter before the justices while President Trump is still in office." The New York Times, &by Maxine Joselow & Lisa Friedman, Feb 10, 2026.

- As the Trump EPA Prepares to Revoke Key Legal Finding on Climate Change, What Happens Next? "Four questions on repeal of its 2009 endangerment finding on greenhouse gases"As the Trump EPA Prepares to Revoke Key Legal Finding on Climate Change, What Happens Next? Inside Climate News, Marianne Lavelle, Feb 11, 2026.

- A look at false claims made by the Trump administration as it revokes a key scientific finding AP News, Melissa Goldin, Feb 12, 2026.

- Trump’s EPA decides climate change doesn’t endanger public health – the evidence says otherwise The Conversation US, Jonathan Levy, Howard Frumkin, Jonathan Patz & Vijay Limaye, Feb 12, 2026.

- Trump delivers a deadly blow to EPA’s ability to regulate climate pollution CNN, Ella Nilsen, Feb 12, 2026.

- The US has revoked what's known as the endangerment finding, an Obama-era scientific finding central to US actions against climate change. Experts say the shift comes at a fragile point for the warming planet. "The US has revoked what's known as the endangerment finding, an Obama-era scientific finding central to US actions against climate change. Experts say the shift comes at a fragile point for the warming planet." Deutsche Welle (DW), Martin Kuebler, Feb 12, 2026.

- Climate leaders condemn Trump EPA’s biggest rollback yet: ‘This is corruption’ "Leaders promise to fight back with court challenges as Trump rescinds finding foundational to US climate rules" The Guardian, Dharna Noor, Feb 12, 2026.

- The Fight Over US Climate Rules Is Just Beginning "As the EPA moves to roll back the endangerment finding, which allows it to regulate greenhouse gases, experts predict uncertainty for business and a protracted legal fight." WIRED, Molly Taft, Feb 12, 2026.

- We love NCAR - Protect it Now! Youtube, The Weather & Climate Livestream, Feb 13, 2026.

Skeptical Science New Research for Week #7 2026

Posted on 12 February 2026 by Doug Bostrom, Marc Kodack

Open access notables

Shifting baselines alter trends and emergence of climate extremes across Africa, Taguela & Akinsanola, Atmospheric Research

World Meteorological Organization baselines used to identify climate extremes are routinely updated to reflect recent climate conditions. Yet the implications of these updates for the characterization, trends, and detectability of climate extremes remain poorly understood, particularly in data-sparse and highly vulnerable regions such as Africa. Here, we quantify how updating the reference period from 1981–2010 to 1991–2020 systematically alters the characterization of temperature and precipitation extremes across the continent. Using multiple observational and reanalysis datasets (BEST, ERA5, MERRA-2, CHIRPS), we assess the sensitivity of percentile-based thresholds, long-term trends, and the Time of Emergence (ToE) to changes in the reference period. ToE is employed here as a diagnostic of detectability rather than a definitive marker of anthropogenic signal onset. Our results show that the updated baseline leads to higher temperature thresholds, resulting in a reduced frequency and slower trends for warm extremes (TX90p, TN90p), and a concurrent increase in cold extremes (TX10p, TN10p). Precipitation extremes exhibit more heterogeneous and dataset-dependent responses: trends in extreme precipitation totals (R95pTOT, R99pTOT) generally weaken, whereas intensity-based metrics (R95pINT, R99pINT) often strengthen, particularly in MERRA-2. Moreover, the choice of baseline strongly influences the estimated ToE. Warm extremes emerge 2–8 years later under the newer baseline, while cold extremes emerge earlier (by up to 15 years) due to enhanced signal-to-noise ratios. For precipitation, ToE responses vary widely across datasets and regions. In CHIRPS, the ToE of intense rainfall events is delayed, whereas in MERRA-2 it advances by over 2 decades in some regions. These results indicate that ToE estimates derived from recent decades are highly sensitive to baseline selection. By explicitly isolating the effect of baseline choice, this study provides a critical framework for interpreting extremes, reconciling dataset discrepancies, and improving the robustness of climate monitoring and risk communication across Africa.

[The same innocently mindless yet deceptive baseline updates pertain in other domains.]

Enhanced weather persistence due to amplified Arctic warming, Graversen et al., Communications Earth & Environment

Changing weather is an aspect of global warming potentially constituting a major challenge for humanity in the coming decades. Some climate models indicate that, due to global warming, future weather will become more persistent, with surface-air temperature anomalies lasting longer. However, to date, an observed change in weather persistence has not been robustly confirmed. Here we show that weather persistence in terms of temperature anomalies, across all weather types and seasons, has increased during recent decades in the Northern Hemisphere mid-latitudes. This persistence increase is linked to Arctic temperature amplification – the Arctic warming faster than the global average – and hence global warming. Persistent weather may lead to extreme weather, and for many plants such as crops, weather persistence can be devastating, as these plants often depend on weather variations. Hence, our results call for further investigation of weather-persistence impact on extreme weather, biodiversity, and the global food supply.

Northward shift of boreal tree cover confirmed by satellite record, Feng et al., Biogeosciences

The boreal forest has experienced the fastest warming of any forested biome in recent decades. While vegetation–climate models predict a northward migration of boreal tree cover, the long-term studies required to test the hypothesis have been confined to regional analyses, general indices of vegetation productivity, and data calibrated to other ecoregions. Here we report a comprehensive test of the magnitude, direction, and significance of changes in the distribution of the boreal forest based on the longest and highest-resolution time-series of calibrated satellite maps of tree cover to date. From 1985 to 2020, boreal tree cover expanded by 0.844 million km2, a 12 % relative increase since 1985, and shifted northward by 0.29° mean and 0.43° median latitude. Gains were concentrated between 64–68° N and exceeded losses at southern margins, despite stable disturbance rates across most latitudes. Forest age distributions reveal that young stands (up to 36 years) now comprise 15.4 % of forest area and hold 1.1–5.9 Pg of aboveground biomass carbon, with the potential to sequester an additional 2.3–3.8 Pg C if allowed to mature. These findings confirm the northward advance of the boreal forest and implicate the future importance of the region's greening to the global carbon budget.

Securing the past for the future – why climate proxy archives should be protected, Bebchuk & Büntgen, Boreas

Glaciers, corals, speleothems, peatlands, trees and other natural proxy archives are essential for global climate change research, but their scarcity and fragility are not equally recognised. Here, we introduce a rapidly disappearing source of palaeoclimatic, environmental and archaeological evidence from some 5000 years ago in the Fenland of eastern England to argue for the protection of natural proxy archives. We describe the region's exceptional, yet neglected subfossil wood sources, discuss its multifaceted value for scholarship and society, and outline a prototype for sustainable proxy preservation. Finally, we emphasise the urgency and complexity of conservation strategies that must balance academic, public and economic interests across different spatiotemporal scales.

From this week's government/NGO section:

Poll Shows GOP Voters Support Solar Energy, American-Made Solar, Fabrizio, Lee & Associates, First Solar

A national poll by the authors found widespread support for solar energy among Republicans, Republican-leaning Independents, and voters who supported President Donald J. Trump. The poll of 800 GOP+ voters found that they are in favor of the use of utility-scale solar by a more than 20-point margin, with 51% in favor; if the panels used for solar energy are American made with no ties to China, support for solar energy soars higher. Those in favor jump to 70%, while only 19% are opposed; 68% agree that the United States needs all forms of electricity generation, including utility solar, to be built for lowering electricity costs, compared to 22% who disagreed; 79% agree that the government should allow all forms of electricity generation, including utility-scale solar, to compete on their own merits and without political interference, versus 11% who disagreed; a clear majority (52%) of GOP+ voters are more likely to support a Congressional candidate if they support an all-of-the-above energy agenda, including the use of solar; and 51% are more likely to vote for a candidate who supported an American company building a solar panel manufacturing plant in the US.

Hot stuff: geothermal energy in Europe, Tatiana Mindeková and Gianluca Geneletti, Ember

Advances in drilling and reservoir engineering are unlocking geothermal electricity across much wider parts of Europe, at a time when the power system needs firm, low-carbon supply and reduced reliance on fossil fuels. Once limited to a few favorable locations, geothermal is now positioned to scale. Around 43 GW of enhanced geothermal capacity in the European Union could be developed at costs below 100 €/MWh today, comparable to coal and gas electricity. The largest potential is concentrated in Hungary, followed by Poland, Germany and France. While representing only a fraction of Europe’s total geothermal potential, the identified EU-level deployment could deliver around 301 TWh of electricity per year, reflecting geothermal’s high capacity factor. This is equivalent to about 42% of coal- and gas-fired generation in the EU in 2025.

178 articles in 67 journals by 1224 contributing authors

Physical science of climate change, effects

Amplifying Variability of the Southern Annular Mode in the Past and Future, Ma et al., Geophysical Research Letters Open Access 10.1029/2025gl119214

An Analytical Model of the Lifecycle of Tropical Anvil Cloud Radiative Effects, Lutsko et al., Open Access pdf 10.22541/essoar.175492939.96377329/v1

These key strategies could help Americans get rid of their cars

Posted on 11 February 2026 by Guest Author

This is a re-post from Yale Climate Connections by Sarah Wesseler

Want to lower your carbon footprint? Consider ditching your car.

In a 2025 study, researchers at the World Resources Institute found that going car-free is the most effective step individuals can take to lower their personal emissions. In fact, it has a bigger impact than adding a home solar system and going vegan combined, they wrote, and 78 times more effective than composting.

But in much of the U.S., getting around without a car is difficult, if not impossible, due to overwhelmingly car-centric infrastructure. However, while going car-free may be hard for many Americans to imagine, this could change. As cities like Amsterdam and Paris have shown, when governments take decisive action to reduce car dependency, the results can be dramatic.

Moreover, the remedies for car dependency are well understood, at least at a high level. Decades’ worth of research from universities, government agencies, nonprofits, and design firms has created a significant body of knowledge about how to reduce reliance on cars.

Susan Handy, who leads the National Center for Sustainable Transportation at the University of California at Davis, said the main takeaways of this research are clear and compelling.

“When people live in more compact communities where they’re in closer proximity to the places they need to go, and when they have good alternatives to driving – meaning good bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure and decent transit service – they will, in fact, drive less,” she said.

(Image credit: Tejvan Pettinger / CC BY 2.0)

(Image credit: Tejvan Pettinger / CC BY 2.0)

Arguments

Arguments

The flicker of a wind turbine shadow is far below the minimum frequency required to trigger photosensitive epilepsy.

The flicker of a wind turbine shadow is far below the minimum frequency required to trigger photosensitive epilepsy.