Filling our atmospheric "tub" with CO2 is easy and fun. Removing it is not.

Bathtubs and Earth's atmosphere overflow if too much water is put in them (think rain).

There is no overflow limit for CO2 (think planet Venus).

A carbon budget tells us how much carbon we can put into the "tub" and keep the warming below a particular level.

Current estimates are that we cause about 2ºC warming per 1000 GtC poured into our "tub" (2ºC per 3600 GtCO2).

Every CO2 emission causes a small, incremental amount of warming.

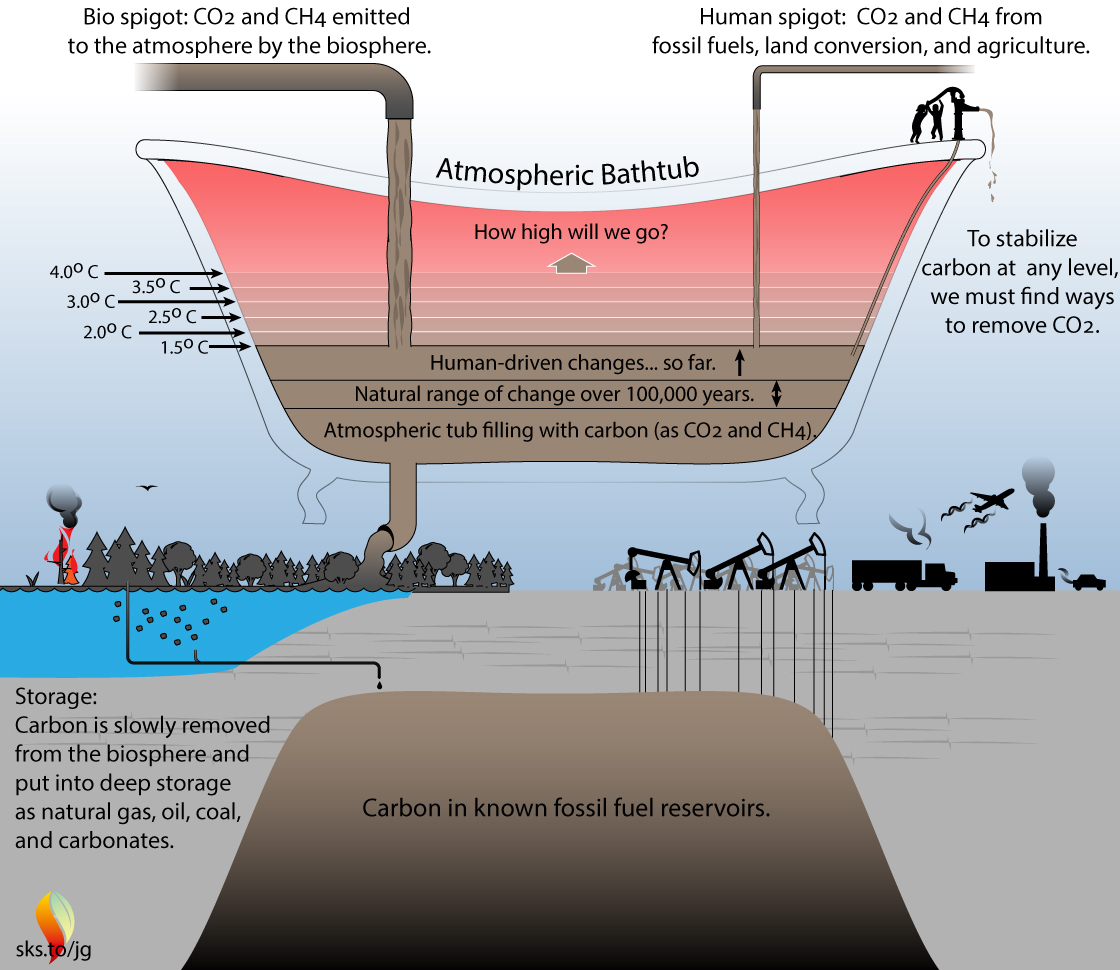

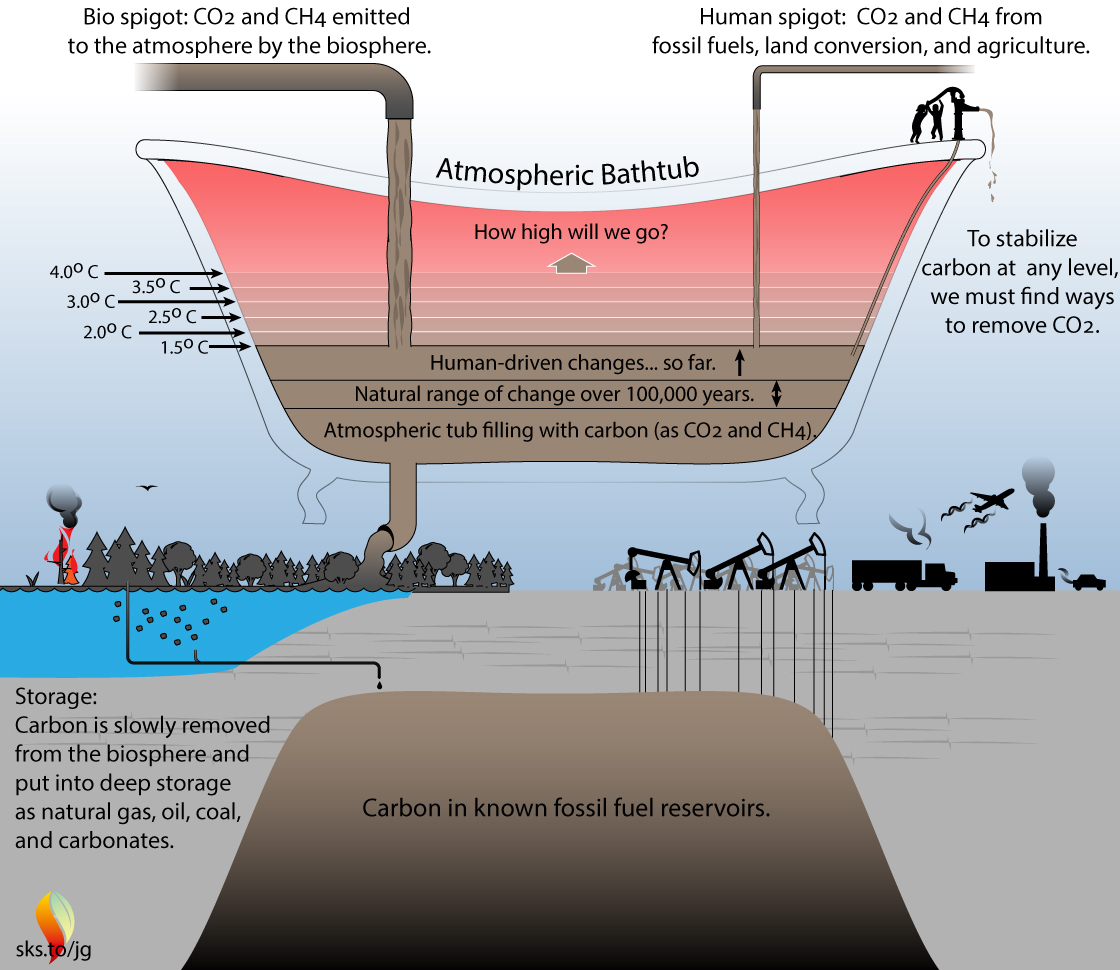

Figure 1. Atmospheric "Bathtub" into and out of which flow carbon streams of natural and human origins. There are no CO2 overflow limits that prevent us from filling this bathtub to dangerous levels .

Earth’s atmosphere has a fixed volume. Human emissions of greenhouse gases (GHGs) are increasing the atmospheric concentration of CO2 in this closed system. The atmosphere has a budget of carbon it can accept to keep overall warming below a certain level. The rings in the bathtub in Fig. 1 are a visual representation of the carbon budget for staying below a given level of warming. A climate sensitivity of 3°C/doubling CO2 (see Ocean Time Lag)1 is consistent with the warming observed since the 1970’s, and is midway in the IPCC estimates that range from a low of 2.5 to a high of 4.0°C/doubling CO2. A climate sensitivity of 3°C/doubling CO2 corresponds to the following levels of warming.2

• 350 ppm CO2 = 1°C warming (warming we think we can live with, see 350.org)

• 400 ppm CO2 = 1.5°C warming (Paris Accord target)

• 450 ppm CO2 = 2°C warming (dangerous warming, but the best we can hope for?)3,4

Beyond 2°C, climatic effects likely become much worse.

There is a set amount of carbon we can emit into the atmosphere to keep the global average temperature below specific target temperatures. Emission rates are meaningless in this context. Lowering emission rates is important to improve the air quality in a large city, but carbon emission rates are meaningless for determining the global warming we will eventually experience: only the total amount emitted matters.

However, emission rates are important for two other reasons.

As the world comes out of an ice age the Earth warms at a rate of about 1°C/1000 years. We therefore know that species are adapted to that rate of change. The current rate of warming of about 20°C/1000 years is far in excess of this natural rate, and many species will likely disappear, even if we stabilize the warming at 2°C. Anything we can do to slow down the rate of warming will help species adapt and buy us needed time to implement solutions.

The problem of motivating action needed to keep total emitted carbon within a 2°C budget is the delay between cause and effect. Specifically…

There is a third problem: comprehending the consequences of blowing a budget. People in “developed” countries live with instant credit, refinancing, bankruptcy, welfare, so many variations of handouts and financial forgiveness that we are used to safety nets to catch us. The concept of no safety net is foreign to people living in affluent societies. For all intents and purposes, there are no natural safety nets that will counteract our GHG emissions.5 At current emission rates, our atmospheric "bathtub" is filling at 2.5 ppm CO2/year. Although there are complicated scenarios for stabilizing temperatures at current levels (read here), broadly referred to as reaching net-zero emissions by 2050, these paths require a seismic shift in how society functions, a shift that has not yet happened on any scale to make a difference. While we continue to hope for a meaningful response to the climate problem, current CO2 levels represent minimum warming, should we fail to coalescence humanity around meaningful climate action and should we fail to achieve net-zero emissions.

There is a growing realization that holding warming to 2°C warming may not be possible (see Glen Peter's excellent summary on this topic). But for those who see a 2°C target as too ambitious, and prefer a longer-term approach of focusing on 3°C as a more attainable target, a caution. We may not have the option to stop the warming at 3°C. By that point, natural, positive feedbacks may drive the temperature higher, no matter what we do. To get a sense of this, compare the sizes of the "Bio spigot" and the "Human spigot" in Fig. 1. Even a small increase in the flow from the Bio-Spigot may overwhelm any reductions in the flow from the Human spigot. There are large uncertainties about how the climate will respond as global temperatures increase, but natural feedbacks will certainly increase with increasing warming, making our emissions reductions less effective at controlling global warming as the planet continues to warm. Above 2°C warming, there is significantly increased uncertainty about our ability to put the brakes on at all.6

A carbon budget for staying below 2°C is the last carbon budget for which there is a consensus among climate scientists that we have a reasonable expectation for controlling our destiny. Beyond that warming, in addition to escalating negative effects, it is unclear how much control we will have over the climate.

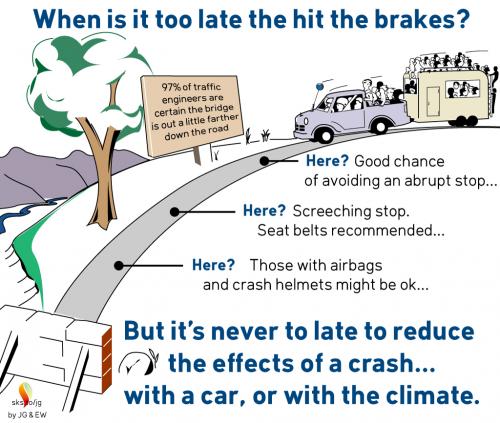

Does this mean it’s too late and we should just give up? If you are driving a car and suddenly realize you are going to run into a brick wall, no matter what you do, at what point is it “too late” to put on the brakes? At the point you put on the brakes you will avoid something worse. Even if it is too late to stop the warming at 2°C, remember that there is uncertainty about the effects associated with these numbers, and that we will always avoid something worse later, by taking action now.

Figure 2. Effects of waiting to apply the brakes. The longer we wait the more severe the consequences, but whenever we put on the brakes, we will avoid a worse outcome.

Please read the NAS booklet on Climate Change: Evidence and Causes. Also, check out Andy Skuce's article: Are we overestimating our global carbon budget?

1. 3°C increase of global average temperature for a doubling of CO2 concentration compared to the pre-industrial level of 280 ppm.

2. Dumping a fixed amount of carbon into the closed system represented by the atmosphere results in a measurable amount of CO2 in the atmosphere, which is quantified as molecules of CO2 (i.e., parts of CO2) per million molecules of air (ppm).

3. (PDF download) Hansen et al. state that 2°C warming could be dangerous.

4. (PDF download) Turn Down The Heat: Why a 4°C Warmer World Must be Avoided.

5. In the physical world there are “safety nets” of sorts, systems that maintain/restore balance, referred to by scientists as "thermostats", which maintain Earth’s climate within habitable bounds. But these processes act far too slowly to counteract the rate at which we are dumping CO2 into the atmosphere. Kind of like comparing the rate of evaporation of water from a bathtub compared to the rate at which it's being filled. The thermostats that control CO2 levels in the atmosphere require 10's to 100's of millennia to restore/maintain balance.

6. I do not have a good reference stating that warming to 3°C will cause uncontrollable feedbacks, but scientists often verbally state this in talks. A good source that infers the probability of uncontrollable feedbacks at 3°C warming is from Hansen et al., where they state "Cumulative emissions of ~1000 GtC, sometimes associated with 2 degrees C global warming, would spur “slow” feedbacks and eventual warming of 3-4 degrees C with disastrous consequences." The implications are that if we target warming for 2°C, and slow feedbacks take us to 3-4°C, then targeting warming for 3°C will likely activate feedbacks that will take us past 4°C, a warming that climate scientists say must be avoided at all costs (See footnote 4 above).

Posted by Evan on Tuesday, 29 November, 2022

|

The Skeptical Science website by Skeptical Science is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. |