Reposted articles from Thinking is Power

In early August 2021 we started to repost selected articles from the Thinking is Power website maintained by Melanie Trecek-King where she regularly writes about many aspects of critical thinking in an effort to provide accessible and engaging critical thinking information to the general public. This page lists the reposted articles in the sequence we shared them in and is intended as a quick reference.

In early August 2021 we started to repost selected articles from the Thinking is Power website maintained by Melanie Trecek-King where she regularly writes about many aspects of critical thinking in an effort to provide accessible and engaging critical thinking information to the general public. This page lists the reposted articles in the sequence we shared them in and is intended as a quick reference.

The phrase “do your own research” seems ubiquitous these days, often by those who don’t accept “mainstream” science (or news), conspiracy theorists, and many who fashion themselves as independent thinkers. On its face it seems legit. What can be wrong with wanting to seek out information and make up your own mind?

Throughout most of our history, humans have sought to understand the world around us. Why do people get sick? What causes storms? How can we grow more food? Unfortunately, until relatively recently our progress was limited by our faulty perceptions and biases.

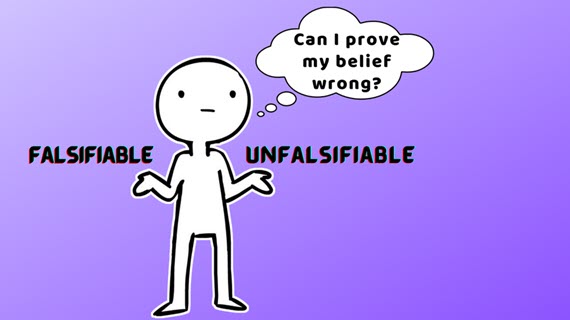

The human brain is a fascinating thing. It’s capable of great things, from composing symphonies to sending people to the moon. Its ability to learn and problem solve is truly awe-inspiring. But the brain is also capable of Olympic-level self-deception. When it wants something to be true, it masterfully searches for evidence to justify the belief. And when it doesn’t want to believe, its ability to deny or discount evidence is (unfortunately) unsurpassed.

Tony Green was convinced that the threat of the virus was being overblown… it was no worse than the flu. It was a scamdemic. As a gay conservative, he was used to fighting for respect, but staying true to his values was important to him. He voted for Donald Trump in 2016, and thought the pandemic was a hoax created by the mainstream media and the Democrats to crash the economy and destroy Trump’s chances at re-election. A self-described “hard-ass,” he stood up for his “God-given rights,” and made fun of people for wearing masks and social distancing. He liked his freedom, and he didn’t want the government telling him what to do.

Everyone thinks. And everyone thinks they’re good at thinking. But good thinking is hard, and it doesn’t come naturally. It’s a skill that has to be learned and practiced. Our brains are adapted to keep us alive by making quick decisions to avoid predators and by forming strong emotional bonds with members of our tribes. Trusting that your brain inherently knows how to reason is a recipe for being misled. And it doesn’t matter how smart or educated you are. No one can lie to us better than we can.

Dorothy Martin awoke early one morning in her suburban Chicago home. Her whole arm was tingling. She didn’t know why, but she picked up a pencil next to her bed and started writing. The words that flowed onto the paper were not her own. Even the handwriting was different. She was receiving a message, a prophecy, from Jesus, currently living on the planet Clarion and going by the name Sananda. Sananda and the other aliens, or Guardians, told Dorothy that she was to spread their messages and teach others how to advance their spiritual development.

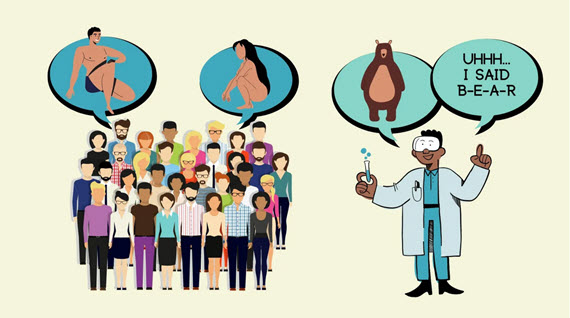

It seems nearly everyone is “doing their own research” these days. And to some extent it’s understandable: we want to make good decisions and there’s a seemingly endless amount of information available at our fingertips. Unfortunately, access to information simply isn’t enough. Although it’s difficult to admit, we aren’t as knowledgeable or as unbiased as we’d like to think we are. We often resort to “doing our own research” when we want (or don’t want) something to be true…and so we set out to find “evidence” to make our case. Due to an unfortunate mixture of motivated reasoning and confirmation bias, we end up wildly misled yet even more confident we’re right. Needless to say, this isn’t how real research works. What you’re actually doing is looking for the results of someone else’s research. The real question is, how do you decide which source to trust?

Post truth. Alternative facts. Fake news. It’s enough to make anyone want to throw in the towel. Information affects how we think and act. A good media diet allows us to make better decisions for ourselves and our families. Unfortunately, there’s a lot of crap out there! Many of us simply decide we can’t believe anything “the media” says, or we retreat into a bubble where we only hear things that confirm what we already think is true.

On November 15, 1912, Mrs. H and her family moved into an old, rambling Victorian house. It had barely been occupied over the previous decade and was falling into disrepair. Lacking electricity, it was lit by gas lamps and always seemed dark. It was only a few days after moving in that the family started to feel a sense of depression. The house’s thick carpeting absorbed the sounds of the family and servants, and the silence was overpowering.

Christ

Dunning and Kruger set out to investigate using psychology’s favorite lab rat… undergraduate students. They asked the students to rate their abilities in logic and grammar relative to other students. Then they actually tested their abilities. The results were shocking. The students who performed the worst consistently and substantially overestimated how well they thought they did. Interestingly, Dunning and Kruger also found the opposite for the top performers, who tended to underestimate their abilities. Their expertise allowed them to recognize their mistakes and see the gaps in their knowledge. Additionally, they assumed that, since something is easy for them, it must be just as easy for everyone else.

As a science educator, my primary goals are to teach students the essential skills of science literacy and critical thinking. Helping them understand the process of science and how to draw reasonable conclusions from the available evidence can empower them to make better decisions and protect them from being fooled or harmed.

We are drowning in misinformation. From celebrities selling their favorite diets and supplements online, to fringe medical “professionals” hawking pseudoscientific treatments on social media, to conspiracy theorists enticing followers down the rabbit hole on youtube, it’s nearly impossible to avoid exposure. We use information to make decisions about everything from our health to how we vote, so being misled by misinformation can cause real harm. Not only is someone usually trying to sell us something, falling for fake “cures” can literally be deadly. While protecting ourselves from misinformation is essential, trying to debunk each and every false claim after it pops up can feel like an overwhelming and endless game of Whac-A-Mole. (Who has the time? Or the energy?)

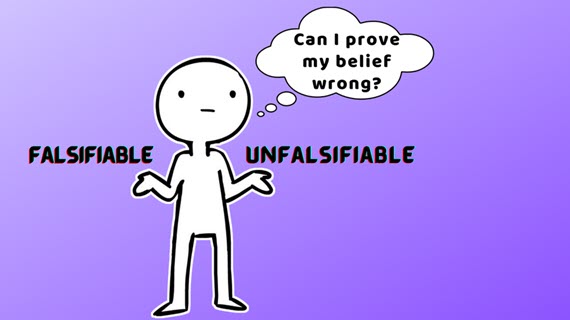

Humans have long sought to explain the world around us. Our ancestors often attributed natural events, like illnesses, storms, or famines, to the work of supernatural forces, such as witches, demons, angry gods, or the spirits of the dead. We notice patterns, even when they’re not real, and we jump to conclusions based on our biases, emotions, expectations, and desires. While the human brain is capable of astonishing levels of genius, it’s also remarkably prone to errors. It’s adapted for survival and reproduction, not for helping us determine the efficacy and safety of a vaccine or determining long-term changes in global climate. Personal experiences and emotional anecdotes can easily fool us, despite how convincing they may seem.

The vocabulary of science can be quite confusing. Not only do scientists use highly technical jargon, they sometimes use the same words as the general public… but with different meanings. Unfortunately, the end result is that scientists can be misunderstood. We use language to communicate complex concepts, so it’s important to understand what someone means when they use a term. Here’s a brief list of six of the most commonly misunderstood words, and what scientists mean when they use them.

The modern world was built by science. From medicine to agriculture to transportation to communication… Science’s importance is undeniable. And yet, people deny science. Not just any science, of course. (Gravity and cell theory are okay, so far.) We’re more motivated to deny conclusions that are perceived to conflict with our identity or ideology, or those in which we don’t like the solutions (i.e., solution aversion). For example, a few of the biggest denial movements today center around vaccines, GMOs (genetically modified organisms), evolution, and climate change, all of which intersect with religious beliefs, political ideology, personal freedoms, and government regulation. But our beliefs are important to us: they become part of who we are and bind us to others in our social groups. So when we’re faced with evidence that threatens these beliefs, we engage in motivated reasoning and confirmation bias to search for evidence that supports the conclusion we want to believe and discount evidence that doesn’t.

Watch this space for more Thinking is Power reposts!

Posted by BaerbelW on Saturday, 11 September, 2021

In early August 2021 we started to repost selected articles from the Thinking is Power website maintained by Melanie Trecek-King where she regularly writes about many aspects of critical thinking in an effort to provide accessible and engaging critical thinking information to the general public. This page lists the reposted articles in the sequence we shared them in and is intended as a quick reference.

In early August 2021 we started to repost selected articles from the Thinking is Power website maintained by Melanie Trecek-King where she regularly writes about many aspects of critical thinking in an effort to provide accessible and engaging critical thinking information to the general public. This page lists the reposted articles in the sequence we shared them in and is intended as a quick reference.