Thinking is Power: The problem with “doing your own research”

Posted on 3 August 2021 by Guest Author

This is a re-post from the Thinking is Power website maintained by Melanie Trecek-King where she regularly writes about many aspects of critical thinking in an effort to provide accessible and engaging critical thinking information to the general public.

This is a re-post from the Thinking is Power website maintained by Melanie Trecek-King where she regularly writes about many aspects of critical thinking in an effort to provide accessible and engaging critical thinking information to the general public.

The phrase “do your own research” seems ubiquitous these days, often by those who don’t accept “mainstream” science (or news), conspiracy theorists, and many who fashion themselves as independent thinkers. On its face it seems legit. What can be wrong with wanting to seek out information and make up your own mind?

Image Credit: Thinkingispower.com

The problems with “doing your own research”

1. That’s not what research is.

Definitions matter. When scientists use the word “research,” they mean a systematic process of investigation. Evidence is collected and evaluated in an unbiased, objective manner, and those methods have to be available to other scientists for replication.

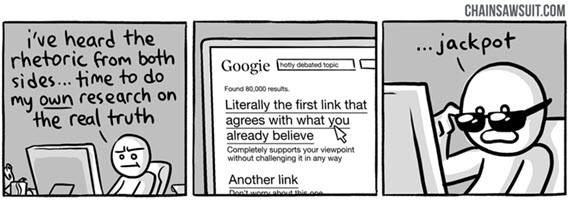

Conversely, when someone says they’re “doing their own research,” they mean using a search engine to find information that confirms what they already think is true. We are all prone to confirmation bias, and the effect is especially powerful when we want (or don’t want) to accept a conclusion.

Science as a process is an attempt to understand reality, and recognizes how biased and flawed the human brain is. That’s why real research is about trying to prove yourself wrong, not right.

Image Credit: Chainsawsuit.com

2. You’re not as smart as you think you are.

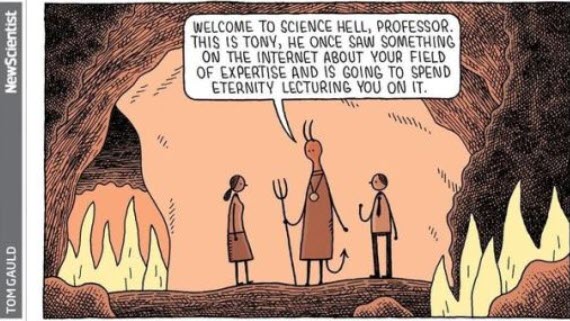

Unless you’re an expert in the field you’re “researching,” you’re almost certainly not able to fully understand the nuance and complexity of the topic. Experts have advanced degrees, published research, and years of experience in their sub-field. They know the body of evidence and the methodologies the researchers use. And importantly, they are aware of what they don’t know.

Can experts be wrong? Sure. But they’re MUCH less likely to be wrong than a non-expert.

Thinking one can “do their research” on scientific topics, such as climate change or mRNA vaccines, is to fool oneself. It’s an exercise in the Dunning-Kruger effect: you’ll be overconfident but wrong.

Yes, information is widely available. But it doesn’t mean you have the background knowledge to understand it. So know your limits

Image Credit: Tom Gauld at New Scientist

The process of science is messy

Science is messy. For example, climate change research involves experts from a variety of fields (e.g. earth sciences, life sciences, physical sciences) and settings (e.g. academia/government/industry), from nearly every country on earth, each looking at the issue using different methods. Their findings have to pass peer review, where other experts evaluate their work before it can be published.

The literature is also messy, as different studies provide different types and qualities of evidence. Different studies also might reach slightly different conclusions, especially if they use different methodologies. Findings that are replicated have stronger validity. And when the various lines of research converge on a conclusion, we can be more confident that the conclusion is trustworthy.

And then there’s the news, which tends to report on new, unique, or sensational findings, generally without the detail and nuance in the literature.

All of this messiness can leave the public thinking that scientists “don’t know anything” and are “always changing their minds.” Or that you can believe whatever you want, as there’s “science” or a “study” or even an “expert” that supports what they want to be true.

Waiting for proof

Most people seem to understand that science is trustworthy. After all, we can thank science and resulting technology for our modern quality of life. Unfortunately, there’s much the public doesn’t understand about science, including the enduring myth that science proves.

Scientific explanations are never proven. Instead, science is a process of reducing uncertainty. Scientists set out to disprove their explanations, and when they can’t, they accept them. Other scientists try to prove them wrong, too. (And scientists LOVE to disagree. Anyone who thinks scientists are able to conspire has never had a conversation with one.) The best way for a scientist to make a name for themselves is to discover something unknown or disprove a longstanding conclusion.

The process of systematic disconfirmation is designed to root out confirmation bias. Those insisting on “scientific proof” before accepting well-established science are either misled or willfully using a fundamental characteristic of science to avoid accepting the science.

Why we should trust science and the experts

Back to “researching.” The danger is that uninformed or dishonest people can cherry pick individual studies, or even an expert, to support a particular conclusion or to make it look like the science is more uncertain than it is…especially if they don’t want to accept it. And if we’re being real, many who “do their own research” are doing so to deny scientific knowledge. But that’s the perfect storm for being misled, and for many scientific issues the price of being wrong is just too high.

Ultimately knowledge is a community effort. We don’t think alone…. and that’s what makes humans a successful species. The problem is that we fail to recognize where our knowledge ends and the community’s begins. That’s why for anyone who isn’t an expert in a particular field, our best chance at knowledge is to trust what the majority of experts in that area say is true. No “research” involved.

To learn more

Forbes: You must not ‘do your own research’ when it comes to science

Thinking Is Power: Don’t be fooled…Fact Check!

Arguments

Arguments

Wonderful summary. Or to put it another way, science is founded on an unspoken principle that: "We Need Each Other, To Keep Ourselves Honest."

In serious science doing your own research (lay or professional) also includes trying to 'prove' one's own ideas wrong. How else can one learn to appreciate the strength's and weakenesses in one's personal assessments?

The root of the issue is very complex. But a few things stand out:

The Guardian article "Yep, it’s bleak, says expert who tested 1970s end-of-the-world prediction" discusses a recent re-evaluation of a 1972 MIT sustainability study that suggested there was no long ter future for the developing dominant socioeconomic games humans played.

In addition to the rapid ending of additional climate change harm due to fossil fuel use, deforestation, and other activities, all of the Sustainable Development Goals, and more, needs to be achieved.

The lack of attention by leadership to Sustainability, even though it was undeniably recognised by global leadership in the 1970s (at the Stockholm Conference and everything that followed), has produced the current day result of "a lack of time to pick and choose and slowly act to correct what has developed".

Big changes are needed rapidly regarding how receptive populations are to actually becoming more aware with improved understanding about what is harmful. That will include severely limiting the ability of competitors for leadership to be able to win through misleading marketing efforts. And that requires ending the false belief in the "equivalency of all Opinions", that irrational misunderstanding of Relativism (everyone's perceptions are their reality).

The efforts to make the required major corrections is not going to be easy, especially in the supposedly superior cultures and nations. But it is undeniably dangerous to compromise better understanding just to get along with people who do not like the idea of better understanding.

Adding to my previous comment:

"Everyone's perceptions are the basis for their understanding of reality" combined with "All opinions are equally valid" challenges efforts to develop a common sense understanding.

A sustainable common sense requires everyone developing it to pursue increased awareness and improved understanding of what is harmful and unsustainable and the need to limit harmful actions.

And in cases like human induced climate change impacts the need is to actually rapidly end the harm being done, not somehow justify extra harm done because it is perceived to be harmful to stop the harm from being done.

The over-development of harmful consumptive ways of living does not mean that developed perceptions of status need to be maintained. Playing that game rewards undeserving winners, encouraging others to try to win more that way. And the wealthy and powerful are well aware of that reality.

By my observation most people appear hopeless when it comes to investigating the credibility of various claims. They get fooled by obvious junk science, cherrypicking of information, misleading claims, the simplest of logical fallacies, self appointed experts without relevant qualifications, emotional manipulation, and anyone in a suit that tells them what they want to hear.

People have little understanding of their own inherent biases and even less ability to control them. They will hold onto ideas that conform with their instincts or preferences despite multiple lines of carefully gathered evidence they are wrong, partly because they are too proud to accept they were mistaken or fooled.

Why do people do all this? Partly because schools and universities do almost nothing (in my experience) to teach them about these things!

I have heard the exact term "Do your own research", from a person who then went on to explain why the science is all wrong.

Needless to say the person was repeating absolute rot about how CO2 is not a greenhouse gas but grows plants etc.

Very hard to put up with needless to say I have never crossed the threshold of the business again.

Dear Melanie,

I fully understand where you are coming from and have had a number of lengthy dsicussions with people whose 'research' mainly consisted of cherry picking.

Nevertheless I cannot accept that all who aren't scientists shall just trust the experts and done. Trust is something that needs to be earned. In this case the science has in my eyes the obligation to explain the findings in a way that as well the non-experts can get an idea of their own what is right and wrong.

Additionally we have got the problem that taking decisions is often interfering with a number of scientific fields and often the experts representing different fields come to different conclusions on such complex matters as how best to fight a Corona pandemic or climate change. Which scientist should a decision maker (and be it a voter) listen to? In my eyes there is definitely a necessity for the ability to form an opinion on your own based on information that you look at.

Best regards Uli

Ulifwischnath:

In science, experts are people trained in the specialized technques, and familiar with all the data, pertaining to their sub-disciplines. The training is done by older experts, who went through the same process in their time. Scientific specialists must only make themselves understood to their specialist peers, who review each other's work, and decide collectively who is or is not an expert. Some scientists communicate their work well to the public, in addition to their peers. Public education isn't a requirement for a successful scientific career, however. IMHO, it behooves a concerned non-expert to at least learn who the genuine experts are, i.e. in the judgment of their specialist peers. John Nielsen-Gammon, Texas State Climatologist, calls for the public schools to teach not so much scientific literacy as scientific meta-literacy:

My point is, if you demand that climate scientists explain their findings so non-experts can understand, you misapprehend scientific culture. Those scientists don't work for you! If you're not willing to make the effort to meet them halfway, you can expect to be disappointed.

I love the author's first link under "To learn more":

You Must Not ‘Do Your Own Research’ When It Comes To Science

Forbes ("The Capitalist's Tool") isn't the first place you'd expect to see that advice, but it's spot-on nevertheless. It's by physicist Ethan Siegel, who had a blog named "Starts with a Bang" a while back, and is a regular contributor on Forbes.com.

There's a good quote in that article,

It comes down to motivations and what is one after, learning or winning an argument. Just like the two forms of debate, a scientific debate where learning is the goal, and honesty is a requirement. Compared to the lawyerly political debate where winning is everything and the truth is treated with contempt and derision.

As a lay-person I've come to appreciate that when I do "my own research" I'm actually doing "homework" collecting as much information as I can to understand a topic.

A serious student questions their own assumptions and wants to understand opposing views because only through dissecting and resolving objections can we truly come to understand our own position.

As for expertise - for the constructive layperson, all it takes is reading scientific papers, to get an inclining of the amazing details scientists are familiar with, which I can barely, or not at all, grasp. It's a good humbling experience.

Finally, possessing a healthy dose of self-skepticism is a prerequisite for constructive learning.

Dear mods, I recall SkS having a CreativeCommons copyright, but now I noticed a regular ©JC in it's place. What's the policy these days regarding reprinting from your blogposts at my own blog? {With acknowledging original authors, etc.}

Thank you, Cc

CC @10

As far as I know we've always had the ©JC on the homepage. If you however for example go to the graphics resources, you'll see the creative commons license at the bottom of the page which also applies for our rebuttals. For blog posts, the CC-license can however not apply to everything but only for the articles created by our team - i.e. those not showing "guest author" at the top. For any reposts you'd have to enquire with the original author/outlet and then link back to them and not SkS.

Does that help?

Baerbel, thank you. Yes, that clears it up quite well.

I am not a doctor, I have never taken a medical course and I am not a health nut. The following three issues, however, define the reason the concept of this thread is crucially important in creating a better tomorrow.

I read a brief article on an interesting non-invasive cardiac test, but my cardiologist recommended against it because conclusions were not always scientifically viable. I told him, as an engineer, more information never resulted in a worse decision, and we went forward with the test. Following the results, the cardiologist said, “I am not sure why you pressed for this test, but the results have identified a previously unknown condition, and I am going to change your treatment regimen.”

I abandoned one sporting activity after another over 50 years with chronic back problems. I ran across a piriformis muscle treatment in a university journal, and during a particularly painful episode suggested it to my orthopedic physician. He replied, the piriformis is not your problem based on my MRI and test data, but again I persuaded the doctor to perform the treatment. In two days my pain subsided and I have used this treatment successfully multiple times since.

Finally, I have type 2 diabetes. With my stable A1 C and glucose levels, my internist indicated for a couple of years I was not at a level that required medication. A non-scientific article suggested the newest opinion on diabetes management offered medication was now being recommended beneath my AI C and blood glucose levels. I am now taking medication to control blood sugar, a medication that has been around for over two decades.

These events certainly do not intend to detract from the contribution being made by medical science, however, they speak to decisions made by scientists on the continuum from art to science on complex issues. On every complex subject, quality conclusions combine proven science and artful judgment. The quality of the scientist's conclusion on the human body and climate management, it seems, is heavily based on his rational acknowledgment of where his database stands on the continuously moving science/art continuum – 60/40, 80/20, 95/5………

I'm not sure the comparison is valid Graydrake. What you are describing is like delving in the cloud feedback litterature and finding a detail that will allow to refine regional forecasts. What is seen in the so-called "doing my own research" crowd when it comes to climate science is more like: "all these scientists have had it wrong but I know where the truth is, look at this YouTube video." Or someone trumpets that there is no GH effect when they clearly have no understanding of the radiative properties of the gases involved.

Medicine is indeed art and science, and there is a big difference between medical practice and medical research. However, you wouldn't give credence to anyone questioning the fact that we are made of cells or that sterile technique must be used to prevent surgical infections.

It is an already well known problem for practitioners that the quantity of new research findings coming out in a constant stream is impossible to keep up with. It would be convenient if there was an IPCC-like body for every specialty, that would synthesize the findings and come up with a "summary for practitioners." There is no such thing, unfortunately, and practitioners who have many patients to manage must rely on practice guidelines established by their specialty's associations and other bodies. These try to keep up but it always takes time to form guidelines, so they appear often years after research has been confirmed.

Doing no harm is the ultimate guiding principle; that often translates into simply doing less, or waiting until there is more scientific evidence. Every medical action or intervention, including diagnostic, carries risks; every medication can have adverse effects. Information obtained from tests and diagnostic procedures is only worth obtaining if it is truly useful and actionable, and the benefits from said action outweighs the risks of both the action and the diagnostic.

It sounds like you're alluding to recent guidelines recommending the use of Metformin outside of the range for which it is approved by the FDA. That may be advisable in some cases but any practitioner faced with that choice must weigh the risks and benefits and make an educated guess of how they will play out for a specific individual. Using a medication off label (i.e. Metformin for someone whose A1C falls below the range of FDA approved use) also carries liability risks for the practitioner. Metformin is not a benign drug. It sounds like you already had a good A1C and low enough blood glucose, what benefit did you obtain from using the medication?

Humans are the ultimate complex system, with a brain that can create therapeutic effects, side effects and even severe adverse effects when given placebos, whether they are placebo drugs or placebo procedures. Devising effective therapies for humans is a constant struggle because of that, and because of the level of refinement that has been attained by medical science. Practitioners also have to contend with people showing all sorts of dysfunctional relations to health and health care: high anxiety, hypocondriacs, Munchausen, and everything in between on the spectrum. You did not expand on your back pain MRI but, from the practitioner's point of view, if there is a well identified cause for it visible on the scan, trying to treat another possible cause is difficult to justify. In fact, practitioners can be questioned by insurance companies and ethics boards if they do that.

The positive outcomes you claim still fall under the "anecdotal" category. Practitioners are obligated to rely on well established evidence before recommending anything to their patients. Of course, we know that's not always the case, and that shooting in the dark can give results, nothing is perfect.