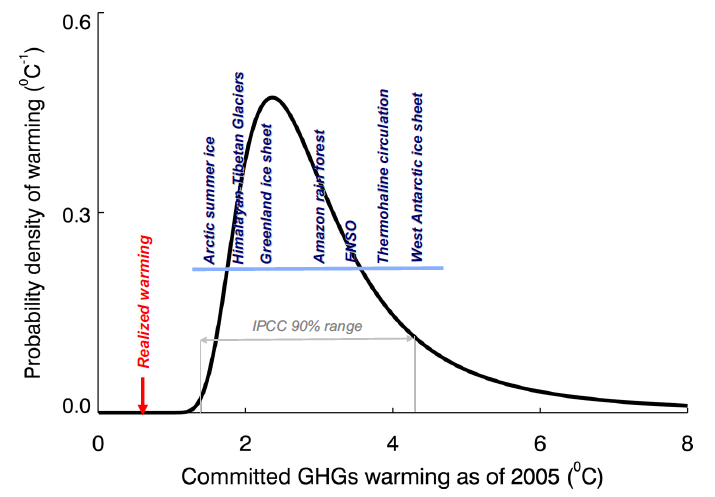

This distribution is based on the warming that we're committed to just based on the greenhouse gases we've emitted thus far. Ramanathan and Fang note that aerosols are likely offsetting a significant amount of global warming, and have a very short lifetime in the atmosphere. So as countries continue to clean their air, aerosols in the atmosphere will quickly decrease, leading to further warming. Ramanathan and Fang estimate that we are most likely already committed to 1.6°C additional warming, which appears sufficient to trigger the eventual collapse of the Greenland Ice Sheet, the Himalayan Tibetan glaciers, and summer Arctic sea ice, among other consequences.

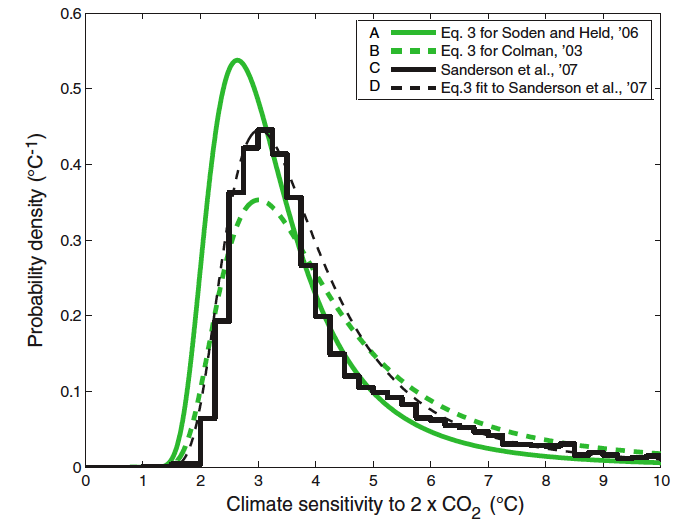

As Bart discussed in the second Prudent Path Week post, aerosols represent a significant uncertainty - one which the "skeptics" try to have both ways, arguing that it's both significantly higher and lower than the IPCC estimates. This aerosol uncertainty is one of the biggest contributors to the large range of possible climate sensitivity values. But even in a best case scenario we are already committed to a dangerous amount of warming. And in a risk assessment, one must also consider the likely and worst case scenarios. In our case, they are not pretty.

As we saw in the third Prudent Path Week post, the "skeptics" have given us little reason to believe that the unlikely low climate sensitivity values are a reality. In fact, on climate sensitivity and aerosols, in their letter to Congress the "skeptics" contradicted themselves by a factor of ten. As Andy showed in the fourth Prudent Path Week post, the carbon cycle feedbacks may cause atmospheric CO2 to rise even faster than the IPCC expects. And as Robert showed in the fifth Prudent Path Week post, we're already seeing significant consequences from the "modest" warming thus far, as the polar regions are both warming and losing ice extensively.

Not only do the "skeptics" want us to ignore the plausible worst case scenarios, but they want us to ignore the most likely scenario. They want us to continue behaving as if there's nothing to worry about. Is this really prudent? That partially depends on the costs of averting climate change.

Costs vs. Benefits

In case you're still not convinced about the prudent path forward, it's worth evaluating every possible scenario. Even if the "skeptics" are right and the better-than-best-case scenario is reality, the costs of reducing carbon emissions are quite small. Moreover, there are additional ancillary benefits to doing so, such as addressing ocean acidification and peak oil. If the "skeptics" are wrong, the benefits of reducing carbon emissions will outweigh the costs several times over. If they're wrong and we fail to act, the most likely scenario is disastrous, and the worst case scenario is catastrophic.

The risks are very asymmetrical. Not only is it more likely that if our estimates of climate sensitivity are wrong, the sensitivity is higher than we think, but the consequences of no action are far worse than the consequences of taking action. The two worst scenarios are:

- if the "skeptics" are right and we limit carbon emissions - in which case the costs will be minimal and we'll still reap the benefits of addressing peak oil, ocean acidification, and other pollutant emissions.

- If the "skeptics" are wrong and we take no action - in which case we will likely experience catastrophic climate change this century.

The second scenario is both far more likely and far more damaging. Risk management requires that we take this scenario seriously.

What's Prudent?

Consider the following analogy: you're driving your car, and you start to feel that the brakes aren't working quite properly. Most people would agree that the prudent path involves spending a modest amount of money to take the car to a mechanic, because if the brakes go out, it presents a potentially catastrophic scenario. This sort of preventative action is good risk management.

In this case we're dealing with the global climate, on which every living thing on the planet relies, and we're facing a disaster in the most likely scenario if we continue on the business-as-usual path which the "skeptics" tell us is "prudent". The "skeptics" would have us continue driving the car in the blind hope that the brakes will never give out. After all, we haven't gotten into a wreck so far, so continuing to drive with faulty brakes must be safe!

To sum up:

- If we continue in a business-as-usual scenario, the results range from bad to catastrophic.

- The cost of reducing carbon emissions and changing paths is minimal.

- The benefits of reducing carbon emissions outweigh the costs several times over.

- In trying to make their case to continue on the business-as-usual path, the "skeptics" contradicted themselves on major issues. By a factor of ten. Twice.

You tell us - what's the prudent path forward?

In their recent letter to US Congress, a group of "skeptic" scientists argued that based on what they deemed the "modest warming" so far, and that the consequences of that warming have thus far been manageable, the "prudent path" forward involves continuing with business-as-usual. However, as the first Prudent Path Week post noted, we're primarily concerned about the warming and climate change that are yet to come.

In their recent letter to US Congress, a group of "skeptic" scientists argued that based on what they deemed the "modest warming" so far, and that the consequences of that warming have thus far been manageable, the "prudent path" forward involves continuing with business-as-usual. However, as the first Prudent Path Week post noted, we're primarily concerned about the warming and climate change that are yet to come.