Explaining climate change science & rebutting global warming misinformation

Global warming is real and human-caused. It is leading to large-scale climate change. Under the guise of climate "skepticism", the public is bombarded with misinformation that casts doubt on the reality of human-caused global warming. This website gets skeptical about global warming "skepticism".

Our mission is simple: debunk climate misinformation by presenting peer-reviewed science and explaining the techniques of science denial, discourses of climate delay, and climate solutions denial.

Fact brief - Is Mars warming?

Posted on 5 April 2025 by Sue Bin Park

![]() Skeptical Science is partnering with Gigafact to produce fact briefs — bite-sized fact checks of trending claims. You can submit claims you think need checking via the tipline.

Skeptical Science is partnering with Gigafact to produce fact briefs — bite-sized fact checks of trending claims. You can submit claims you think need checking via the tipline.

Is Mars warming?

Mars’ climate varies due to completely different reasons than Earth’s, and available data indicates no temperature trends comparable to Earth’s recent warming.

Mars’ climate varies due to completely different reasons than Earth’s, and available data indicates no temperature trends comparable to Earth’s recent warming.

Mars lacking oceans or a robust atmosphere means its climate is highly susceptible to external factors. In the longer term, its non-circular orbit causes heating when passing closer to the sun and cooling when further away. In the short term, weather patterns like dust storms impact how much solar heat reaches Mars.

Mars warming would imply that the sun is causing generally rising planetary temperatures. However, total solar heat has decreased since the 1980s. Moreover, analyses of the available 50 years of Mars data found seasonal variability, but no warming trend.

Meanwhile, Earth has warmed 1.5°C (2.7°F) since the 1880s due to the greenhouse effects of human-made CO2. Our best understanding of available Mars data indicates no warming nor mechanisms comparable to Earth’s recent climate change.

Go to full rebuttal on Skeptical Science or to the fact brief on Gigafact

This fact brief is responsive to quotes such as the one highlighted here.

Sources

New Scientist Climate myths: Mars and Pluto are warming too

Nature Global warming and climate forcing by recent albedo changes on Mars

American Geophysical Union Some Coolness on Martian Global Warming and Reflections on the Role of Surface Dust

SPACE.com Mars' atmosphere: Facts about composition and climate

NASA Graphic: Temperature vs Solar Activity

Solar System Research Seasonal Variation of Martian Surface Temperature over Gale Crater and Surroundings

NASA Global Temperature

Skeptical Science New Research for Week #14 2025

Posted on 3 April 2025 by Doug Bostrom, Marc Kodack

Open access notables

A pronounced decline in northern vegetation resistance to flash droughts from 2001 to 2022, Zhang et al., Nature Communications:

Here we show that vegetation resistance to flash droughts declines by up to 27% (±5%) over the Northern Hemisphere hotspots during 2001-2022, including eastern Asia, western North America, and northern Europe. The notable decline in vegetation resistance is mainly attributed to increased vapour pressure deficit and temperature, and enhanced vegetation structural sensitivity to water availability. Flash droughts pose higher ecological risks than slowly-developing droughts during the growing seasons, where ecosystem productivity experiences faster decline rates with a shorter response time. Our results underscore the limited ecosystem capacity to resist flash droughts under climate change.

Climate denial and the classroom: a review, Kutney, Geoscience Communication:

Climate change awareness is floundering across the globe despite climate change education being embedded in international treaties to address the climate crisis – the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (the UNFCCC) and the subsequent Paris Agreement. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) acknowledges forces hostile to climate awareness and education – namely, climate denial sponsored by the energy-industrial complex. Climate change is studied by the physical sciences, but climate denial is the purview of the social sciences; the latter has revealed the why and how of climate denial. Climate-denial organizations (which directly deny aspects of the scientific consensus on climate change) and the related petro-pedagogy groups (which teach that oil is a benefactor to humanity, but say little about the connection of fossil fuels to the climate crisis) have arisen to attempt to interfere with the teaching of the science of climate change in school classrooms. These organizations were found in the United States, Canada, and some European nations (this review is mainly restricted to English-language sources). This review aims to (1) provide an overview of climate denial, promoted and funded by the energy-industrial complex; (2) identify and examine organizations involved in climate denial in schools; (3) summarize the strategies of climate-denial organizations in school classrooms; and (4) put forward recommendations for further research and action.

Most Christian American religious leaders silently believe in climate change, and informing their congregation can help open dialogue, Syropoulos & Sparkman, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences:

Nearly 90% of U.S. Christian religious leaders believe in anthropogenic climate change, with most believing human activity is a major contributor. Yet roughly half have never discussed it with their congregation, and only a quarter have mentioned it more than once or twice. U.S. Christians substantially underestimate the prevalence of their leaders who believe in climate change. Providing the actual consensus level of religious leaders’ belief in climate change reduces congregants’ misperception of religious leaders, increases their perception that other church members believe in and are open to discussing climate change, and leads Christians to believe that taking climate action is consistent with their church’s values while voting for politicians who will not take climate action is not.

Why do Australians prefer some climate migrants over others?, Martínez i Coma & Birch, Environmental Politics:

We investigate attitudes toward climate migration in Australia, exploring support for different climate migrants and the role of environmental attitudes in conditioning this support. After confirming the results of previous studies on other countries – climate migrants fall in the middle of the preference scale over migrant types – we offer novel evidence that individuals attaching greater salience to the environment are more likely to distinguish between different types of climate migrants. We attribute this result to the level of cognitive engagement with climate migration. We address these questions via a representative online survey which embeds a conjoint experiment, combined with 25 interviews with federal and state members of parliament. Overall, Australians, and especially those for whom the environment is salient, prefer migrants coming due to rising sea levels over those migrating due to drought. The analysis of the MP interviews suggests a logic to interpret these preferences.

Climate obstruction at work: Right-wing populism and the German heating law, Haas et al., Energy Research & Social Science:

The intense debates surrounding the so-called heating law (Gebäudeenergiegesetz, GEG) in Germany demonstrate that socio-technical transitions and policies aimed at achieving net zero should be conceptualized as socially contested processes to adequately reflect their societal and political character. We argue that more recent research on sustainable transitions that looks at the role of incumbent actors, and especially the concept of ‘climate obstruction’ is helpful for better understanding the delay of climate policies. Based on this assumption, we analyze the campaign against the law and identify five central discursive strands brought forward to dismantle the law: Expropriation (1), Disenfranchisement (2), Ideological Driven (3), Green Cronyism (4), and Demand to Take Everyone Along (5).

From this week's government/NGO section:

Consecutive extreme heat and flooding events in Argentina highlight the risk of managing increasingly frequent and intense hazards in a warming climate, Zachariah et al., World Weather Attribution

To assess to what extent human-induced climate change altered the likelihood and intensity of the heavy precipitation leading to the severe flooding in Argentina, as well as the extreme heat the authors undertook an attribution study for the extreme rainfall in the most affected region, that coincides with the area where flood warnings were in place. Climate models show that climate change is making such temperatures much more frequent and intense. However, the increase in the models is smaller than in reanalysis products and thus likely underestimating the effect of climate change. Nevertheless, looking at the future, models show a very strong trend that increases with future warming, rendering such an event a common occurrence in a 2.6°C warmer climate compared to pre-industrial. The influence of climate change on the rainfall event is much less clear. While all of the 35 available weather stations in the area show an increase in the intensity of heavy rainfall of between 7-30% associated with global warming of 1.3°C, this is not represented in any of the available gridded reanalysis products which show on average a decreasing trend.

State of the Climate in Latin America and the Caribbean 2024, Marengo et al., World Meteorological Organization

The authors provide the status of key climate indicators and information on climate-related impacts and risks. They address specific physical science, socio-economic, and policy-related aspects that are relevant to Latin America and the Caribbean and respond to Members needs in the fields of climate monitoring, climate change, and climate services. For example, the mean temperature in Latin America and the Caribbean in 2024 was +0.90 °C above the 1991–2020 average, making 2024 the warmest or second warmest year on record, depending on the dataset used.

118 articles in 55 journals by 809 contributing authors

Physical science of climate change, effects

The greater role of Southern Ocean warming compared to Arctic Ocean warming in shifting future tropical rainfall patterns, Park et al., Open Access pdf 10.21203/rs.3.rs-5139656/v1

Observations of climate change, effects

Abrupt sea level rise and Earth’s gradual pole shift reveal permanent hydrological regime changes in the 21st century, Seo et al., Science 10.1126/science.adq6529

Two-part webinar about the scientific consensus on human-caused global warming

Posted on 2 April 2025 by BaerbelW, John Cook

In February 2025, John Cook gave two webinars for republicEN explaining the scientific consensus on human-caused climate change.

20 February 2025: republicEN webinar part 1 - BUST or TRUST? The scientific consensus on climate change

In the first webinar, Cook explained the history of the 20-year scientific consensus on climate change. How do we know there’s a scientific consensus on climate change? How did we get there, and what exactly does it all mean?

The webinar "Bust or Trust? The scientific consensus on climate change," focused on establishing that there is a scientific consensus on climate change and how to communicate that effectively.

The existence of a scientific consensus is supported by multiple studies conducted over the past 15 years. These studies consistently show that over 90% of climate experts agree that humans are causing global warming, with many studies finding agreement around 97-98%. This consensus has been demonstrated through various research methods, including surveys of scientists and analyses of published climate papers.

Despite this overwhelming scientific agreement, public perception of the consensus remains low. Only 30-50% of people believe that scientists agree on global warming. This gap between scientific consensus and public perception is due to several factors, including cultural and political biases, misinformation, and a lack of awareness. The webinar emphasized the importance of effectively communicating the scientific consensus to bridge this gap and promote informed action on climate change.

The first presentation can be downloaded as a PDF (5MB).

Sabin 33 #22 - How does waste from wind turbines compare to waste from fossil fuel use?

Posted on 1 April 2025 by Ken Rice

On November 1, 2024 we announced the publication of 33 rebuttals based on the report "Rebutting 33 False Claims About Solar, Wind, and Electric Vehicles" written by Matthew Eisenson, Jacob Elkin, Andy Fitch, Matthew Ard, Kaya Sittinger & Samuel Lavine and published by the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia Law School in 2024. Below is the blog post version of rebuttal #22 based on Sabin's report.

Roughly 85% of the mass of a wind turbine, including the tower, gearbox, and generator, consist of metals that are easily recycled1 (also Khalid et al. 2023). The remaining 15%, including the blades, consist of composite-based materials, such as fiberglass, that are more difficult to recycle (Khalid et al. 2023). However, new technologies are in development for recycling turbine blades, and turbine blades are in fact being recycled in some facilities2 (also Jensen & Skelton 2023). A recent breakthrough supported by the Department of Energy enabled all turbine components to be recycled3, and private companies in the United States have begun developing turbine blade recycling plants.4

One study from 2017 estimated that global annual waste of turbine blades will reach 2.9 million metric tons per year by 2050, with a total of 43 million metrics tons in cumulative waste generated between 2018 and 2050 (Liu & Barlow 2017). This is not insignificant. However, Nature Physics has projected that global cumulative waste from fossil fuel-based power generation between 2016 to 2050 is expected to produce roughly 45,550 million metric tons of coal ash alone, along with 249 million metric tons of oily sludge (Mirletz et al. 2023). In other words, the cumulative waste from coal ash is expected to be roughly 1,000 times greater than that of turbine blades, and the cumulative waste of oily sludge is expected to be about 5-6 times greater than that of turbine blades. Importantly, both coal ash and oily sludge are known to be toxic. For further context, in the United States alone, roughly 600 million short tons, or 544 million metric tons, of construction and demolition debris were generated across all sectors in 2018.5 In effect, the annual construction and demolition waste in the United States alone is roughly 187 times greater than the anticipated annual waste from wind turbine blades across the globe in 2050.

Clean energy generates major economic benefits, especially in red states

Posted on 31 March 2025 by Guest Author

This is a re-post from Yale Climate Connections by Karin Kirk

When former President Joe Biden left office, the Department of Energy was overseeing more than $300 billion in public and private investments in clean energy under the Inflation Reduction Act. Nearly three-quarters of these investments were slated to flow to states that voted for President Donald Trump in the 2024 election, a Yale Climate Connections analysis shows.

But on the first day of his second term, President Donald Trump signed an executive order attempting to halt some payments under that law, with the potential to hurt his own voters the most.

A landmark climate law

The Inflation Reduction Act, or IRA, passed by Democrats in 2022, made ambitious commitments to modernize the nation’s energy sources, boost competitiveness in new energy technology, grow American manufacturing jobs, and reduce climate-warming pollution. It committed at least $369 billion to energy and climate programs, to be distributed through multiple programs and agencies over 10 years.

The Trump administration has attempted to pause further payments from the IRA, including those that had been already approved. For example, the administration froze funding for the Environmental Protection Agency’s Solar for All program, which had already begun giving out $7 billion in grants to help purchase and install solar panels for lower-income households. Weeks later, the funding for that program was restored, and it remains unclear if courts will allow the Trump administration to freeze IRA funding that had already been appropriated.

The uncertainty around many IRA programs seems likely to disrupt planning for new projects and investments. This is especially true for projects with a multiyear planning process, such as battery factories, electrical grid upgrades, and electric vehicle plants. The situation is ever-evolving, and you can track recent changes with the Inflation Reduction Act Tracker.

How the Inflation Reduction Act works

- The IRA aims to reduce climate-warming pollution across many facets of society and is funded through multiple government agencies.

- For example, the EPA offers rebates for clean heavy-duty vehicles, the USDA is funding efforts to improve soil carbon uptake on farmlands, and the Department of Energy is using tax credits to incentivize the construction of new clean energy projects. The Inflation Reduction Act Database lists the programs at each agency.

- The federal government provides direct funding to projects in some cases.

- In other cases, the government offers a tax credit as an incentive for a private company to build a new project. For clean energy projects, these private investments are greater than the government funding. For example, spending $740 billion in tax credits from the IRA was expected to generate $2 trillion in private investments.

- Funding for energy and climate programs under the IRA was originally expected to cost $391 billion. Since then, many of the tax credits have proved to be more popular than originally anticipated. As more companies and individuals claim tax credits, this raises the price tag of the IRA, but it expands the benefits, too.

2025 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming News Roundup #13

Posted on 30 March 2025 by BaerbelW, Doug Bostrom, John Hartz

This week's roundup is again published by category and sorted by number of articles included in each. The formatting is a bit different compared to previous weeks, though. We are still interested in feedback to hone the categorization, so if you spot any clear misses and/or have suggestions for additional categories, please let us know in the comments. Thanks!

Stories we promoted this week, by category:

Climate Change Impacts (11 articles)

- March 23: Imperiled in the Wild, Many Plants May Survive Only in Gardens, Yale Environment 360, Janet Marinelli. As the impacts of climate change and other threats mount, conservationists are racing to preserve endangered plant species in botanical garden “metacollections” in the hope of eventually returning them to the wild. But what happens when there is no suitable habitat to return them to?

- March 23: Glacier melt threatens water supplies for two billion people, UN warns, Ice, Carbon Brief, Ayesha Tandon. Climate change and “unsustainable human activities” are driving “unprecedented changes” to mountains and glaciers, threatening access to fresh water for more than two billion people, a UN report warns.

- March 24: Wildfires in the Carolinas burn more than 6,000 acres, prompting evacuations, a burn ban and National Guard deployment, CNN Weather, Karina Tsui.

- March 25: From deluges to drought: Climate change speeds up water cycle, triggers more extreme weather, Climate, AP News, Tammy Webber & Donavon Brutus.

- March 26: Forecasting the future of Southern Ocean ecosystems, Phys.org, Rebecca Owen, Eos .

- March 27: Is climate science the next power source for renewable energy?, UN News, Laura Quinones. As solar, wind, and hydropower expand, scientists say integrating climate data and forecasting is key to making renewable systems stronger.

- March 28: China’s glacier area shrinks by 26% over six decades due to global warming, CNN World, Reuters.

- March 28: Despite Staff and Budget Cuts, NOAA Issues Critical Drought Warnings in Its Spring Climate Outlook, Science Inside Climate News , Bob Berwyn. The embattled agency continues to disseminate crucial updates in a hostile political environment, while scientists warn that cutting climate intelligence is folly at a time of escalating climate extremes.

- March 28: Fires rage, spread across Carolinas as central US braces for severe weekend weather, Nation, USA TODAY, Christopher Cann.

- March 29: Earth’s Land Masses Are Drying Out Fast, Scientists Warn, Science, inside Climate News, Bob Berwyn. Researchers comparing satellite measurements of the planet’s water with the wobble in its rotation identified a steady loss of global soil moisture.

- March 29: Arctic sea ice winter peak in 2025 is smallest in 47-year record, ice, Carbon Brief, Ayesha Tandon. Arctic sea ice has recorded its smallest winter peak extent since satellite records began 47 years ago, new data reveals.

Skeptical Science New Research for Week #13 2025

Posted on 27 March 2025 by Doug Bostrom, Marc Kodack

Open access notables

New coasts emerging from the retreat of Northern Hemisphere marine-terminating glaciers in the twenty-first century, Kavan et al., Nature Climate Change:

Accelerated climate warming has caused the majority of marine-terminating glaciers in the Northern Hemisphere to retreat substantially during the twenty-first century. While glacier retreat and changes in mass balance are widely studied on a global scale, the impacts of deglaciation on adjacent coastal geomorphology are often overlooked and therefore poorly understood. Here we examine changes in proglacial zones of marine-terminating glaciers across the Northern Hemisphere to quantify the length of new coastline that has been exposed by glacial retreat between 2000 and 2020. We identified a total of 2,466 ± 0.8 km (123 km a−1) of new coastline with most (66%) of the total length occurring in Greenland. These young paraglacial coastlines are highly dynamic, exhibiting high sediment fluxes and rapidly evolving landforms. Retreating glaciers and associated newly exposed coastline can have important impacts on local ecosystems and Arctic communities.

Quantifying both socioeconomic and climate uncertainty in coupled human–Earth systems analysis, Morris et al., Nature Communications:

Information about the likelihood of various outcomes is needed to inform discussions about climate mitigation and adaptation. Here we provide integrated, probabilistic socio-economic and climate projections, using estimates of probability distributions for key parameters in both human and Earth system components of a coupled model. We find that policy lowers the upper tail of temperature change more than the median. We also find that while human system uncertainties dominate uncertainty of radiative forcing, Earth system uncertainties contribute more than twice as much to temperature uncertainty in scenarios without fixed emissions paths, reflecting the uncertainty of translating radiative forcing into temperature. The combination of human and Earth system uncertainty is less than additive, illustrating the value of integrated modeling. Further, we find that policy costs are more uncertain in low- and middle-income economies, and that renewables are robust investments across a wide range of policies and socio-economic uncertainties.

Thirstwaves: Prolonged Periods of Agricultural Exposure to Extreme Atmospheric Evaporative Demand for Water, Kukal & Hobbins, Earth's Future:

The atmosphere is getting more demanding for water around the world, and this affects water use and farming outcomes. Previously, studies mainly looked at the overall atmospheric demand for water, but little is known about changes in occurrence of very high atmospheric demand for water over consecutive days. In this study, we use introduce the idea of “thirstwaves,” which are long periods of very high atmospheric demand for water. We looked at these thirstwaves that have occurred during 1981–2021 in the US and analyzed them for how intense and how frequent they were and how many days they lasted. We found that the worst thirstwaves happened in places that do not see the highest demand. Over time, all aspects of these thirstwaves have gotten worse. It has also become much less likely that a growing season will pass without any thirstwaves. These findings suggest that in addition to monitoring overall atmospheric demand for water, it's important to track, measure, and report thirstwaves to those managing agriculture and water resources.

KlimaSeniorinnen case: Climate change legal scholarship needs empiricism, not hype, Bétaille & Chapron, PLOS Climate:

In April 2024, the European Court of Human Rights ruled in the KlimaSeniorinnen case that Switzerland had not implemented a legal framework capable of addressing climate change and that this constituted a violation of the right to private and family life. Despite being celebrated as “historic,” this ruling reflects established case law rather than a legal breakthrough. Hyperbolic reactions reveal a lack of empirical rigor in legal commentary, which undermines evidence-based climate policymaking. We caution against exaggerating the impact of individual rulings, given limited evidence of their influence on climate policies and emissions reductions, and encourage legal scholars to instead adopt methodological rigor akin to practices in other scientific disciplines. Specifically, we advocate for empirical approaches in law, through comprehensive data collection, robust statistical methods, and systematic analysis to better understand the role of courts in climate change mitigation.

COP29: From mitigation tragedy to finance farce, Harris, PLOS Climate:

The twenty-ninth conference of the parties (COP29) to the 1992 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) met in November 2024 in Baku, Azerbaijan. The resulting Baku Climate Unity Pact comprised several agreements on greenhouse gas (GHG) mitigation, climate finance and adaptation. The pact demonstrated an unfortunate unity on two things: there is no concerted global determination to do what is necessary to cut, let alone cut rapidly, the anthropogenic causes of climate change, nor is there sufficient collective will to limit markedly its painful manifestations on vulnerable societies.

From this week's government/NGO section:

Liability Considerations for Marine Carbon Dioxide Removal Projects in U.S. Waters, Silverman-Roati et al, Columbia Law School

Scientists have identified several land- and ocean-based carbon dioxide removal (“CDR”) approaches. Ocean-based approaches, also known as marine CDR, hold great potential for the uptake and sequestration of carbon dioxide. However, controlled field trials in the ocean are needed to better understand the efficacy and impacts of several marine CDR approaches. Legal considerations will have a major bearing on whether, when, where, and how much field research goes forward. Previous studies have analyzed the potential international and domestic legal framework applicable to marine CDR research and subsequent deployment if that is ultimately deemed appropriate. However, relatively little research has analyzed the potential for this legal framework to impose liability on marine CDR project proponents (e.g., for environmental harms resulting from their activities). The authors begin to fill that gap about projects in U.S. ocean waters by analyzing potential liability for marine CDR project proponents under U.S. federal statute, and federal and state tort law.

Media coverage of AEMO’s Gas Statement of Opportunities. Using the Australia Institute’s ‘scare scale’ to analyse coverage of Australia’s gas shortage myth, Black et al,. The Austrailia Institute

Australia is one of the world’s largest producers of gas, yet Australians are routinely told that the country is about to run out of gas for domestic use. A key moment each year for the propagation of Australia’s gas shortage myth is the release of the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO)’s Gas Statement of Opportunities (GSOO). With the 2025 GSOO scheduled to be released in March, the authors have analysed coverage of the 2024 GSOO using a new method – the “scare scale”. The scare scale measures emotive words such as “crisis”, “dark” and “blackout” as a portion of total word count of relevant articles.

134 articles in 58 journals by 828 contributing authors

Physical science of climate change, effects

Arctic warming as a potential trigger for the warm blob in the northeast Pacific, Chen et al., npj Climate and Atmospheric Science Open Access 10.1038/s41612-025-00900-9

Deep ocean cooling and freshening from Subpolar North Atlantic reaches Subtropics at 26.5°N, Chomiak et al., Communications Earth & Environment Open Access 10.1038/s43247-025-02170-y

Climate skeptics have new favorite graph; it shows the opposite of what they claim

Posted on 26 March 2025 by Zeke Hausfather

This is a re-post from the Climate Brink

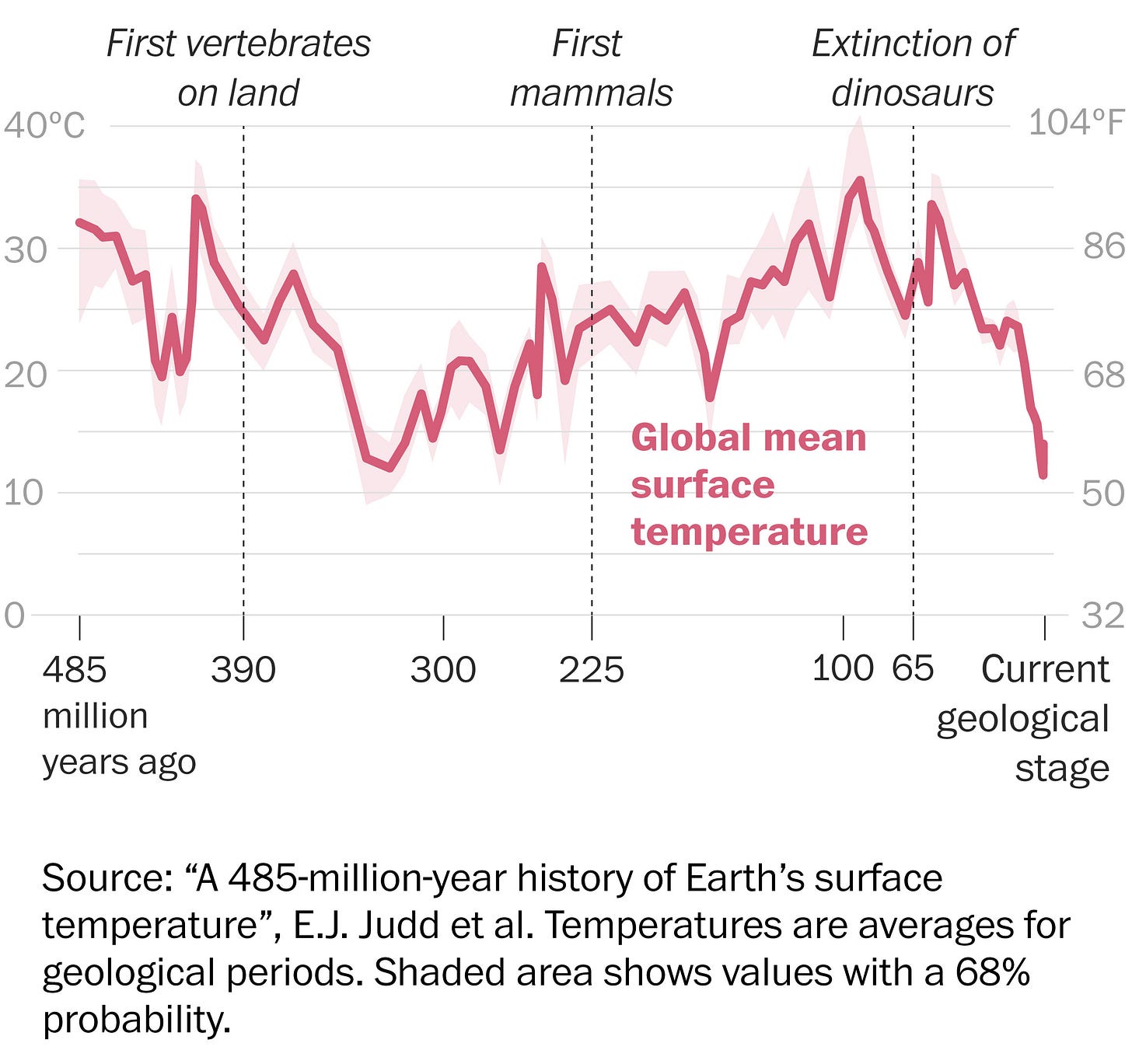

Last September the Washington Post published an article about a new paper in Science by Emily Judd and colleagues. The WaPo article was detailed and nuanced, but led with the figure below, adapted from the paper:

The internet, being less prone to detail and nuance, ran with the figure, with climate skeptics calling it their “new favorite graph” and reposting it everywhere, claiming that it shows the insignificance of recent human warming relative to the Earth’s long temperature history.

The furor over the graph reached its apogee in January when Joe Rogan showed it in a podcast interview with Mel Gibson, saying that “If you believe these silly people, way before human beings had ever existed, there's always this rise and fall. And this idea that the whole thing is based on carbon emissions from human beings is total bullshit. It's not true. Right. We might be having an effect, but we're having a small effect, a very small effect.”

Sabin 33 #21 - How does production of wind turbine components compare with burning fossil fuels?

Posted on 25 March 2025 by Ken Rice

On November 1, 2024 we announced the publication of 33 rebuttals based on the report "Rebutting 33 False Claims About Solar, Wind, and Electric Vehicles" written by Matthew Eisenson, Jacob Elkin, Andy Fitch, Matthew Ard, Kaya Sittinger & Samuel Lavine and published by the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia Law School in 2024. Below is the blog post version of rebuttal #21 based on Sabin's report.

On a lifecycle basis, wind power emits far less carbon dioxide than fossil fuels per kilowatt-hour of energy generated (Dolan & Heath 2012, Wang et al. 2019). According to the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), the average lifecycle emissions of offshore and onshore wind turbines is 13 g CO2-eq/KWh.1 Lifecycle emissions for fossil fuels are much higher, with natural gas and coal releasing 486 g CO2-eq/KWh and 1001 g CO2-eq/KWh emissions, respectively.1 In other words, the average lifecycle emissions of wind energy is roughly 1/77th that of coal.1

Manufacturing accounts for only a small percentage (2.41%) of the lifecycle emissions for wind power turbines (Wang et al. 2019). Most turbine emissions come from transportation, which accounts for over 90% of emissions for both offshore and onshore operations. Once operational, wind turbines create clean, emissions-free energy that offsets the carbon dioxide emissions associated with production and transportation.2

China will need 10,000GW of wind and solar by 2060

Posted on 24 March 2025 by Guest Author

This is a re-post from Carbon Brief by Wang Zhongying, chief national expert, China Energy Transformation Programme of the Energy Research Institute, and Kaare Sandholt, chief international expert, China Energy Transformation Programme of the Energy Research Institute

China will need to install around 10,000 gigawatts (GW) of wind and solar capacity to reach carbon neutrality by 2060, according to new Chinese government-endorsed research.

This huge energy transition – with the technologies currently standing at 1,408GW – can make a “decisive contribution” to the country’s climate efforts and bring big economic rewards, the China Energy Transformation Outlook 2024 (CETO24) shows.

The report was produced by our research team at the Energy Research Institute of the Chinese Academy of Macroeconomic Research – a “national high-end thinktank” of China’s top planner the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC).

The outlook looks at two pathways to meeting China’s “dual-carbon” climate goals and its wider aims for economic and social development.

In the first pathway, a challenging geopolitical environment constrains international cooperation.

The second assumes international climate cooperation continues despite broader geopolitical tensions.

We find that, under both scenarios, China’s energy system can achieve net-zero carbon emissions before 2060, paving the way to make Chinese society as a whole carbon neutral before 2060.

However, the outlook shows that meeting these policy goals will not be possible unless China improves its energy efficiency, sustains its electrification efforts and develops a power system built around “intelligent” grids that are predominantly supplied with electricity from solar and wind.

2025 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming News Roundup #12

Posted on 23 March 2025 by BaerbelW, Doug Bostrom, John Hartz

This week's roundup is again published by category and sorted by number of articles included in each. We are still interested in feedback to hone the categorization, so if you spot any clear misses and/or have suggestions for additional categories, please let us know in the comments. Thanks!

Stories we promoted this week, by category and number of articles shared:

Climate Change Impacts (14 articles)

- Global sea level rose faster than expected in 2024, according to NASA analysis Ocean water expands as it warms, researchers said. by Julia Jacobo, International, ABC News, Mar 14, 2025

- How Can We Help People Who Cannot Flee High Climate-Risk Zones? by Columbia Climate School, State of the Planet, Mar 17, 2025

- One Devastating Storm System: What to Know About the Havoc The tornadoes, dust storms and wind-fanned wildfires have led to at least 40 deaths across the United States t The tornadoes, dust storms and wind-fanned wildfires have led to at least 40 deaths across the United States this past week. by Isabelle Taft, Adeel Hassan, Hank Sanders & Amy Graff, New York Times, Mar 16, 2025

- Earth is ‘perilously close’ to a global warming threshold. Here’s what to know by Interview by Ali Rogan, PBS Weekend News, Mar 16, 2025

- New Zealand could face twice as many extreme atmospheric rivers, NIWA says by Staff, New Zealand, RNZ, Mar 18, 2025

- Cross-country storm unleashes blizzard as its winds fan wildfires across the central US by Robert Shackelford, Karina Tsui & Mary Gilbert, CNN Weather, Mar 19, 2025

- Global Warming Can Lead to Inflammation in Human Airways, New Research Shows Drier air caused by climate change poses respiratory health risk by dehydrating airways, researchers say by Staff, Johns Hopkins Newsroom, Mar 17, 2025

- More than 150 ‘unprecedented’ climate disasters struck world in 2024, says UN Floods, heatwaves and supercharged hurricanes occurred in hottest climate human society has ever experienced by Damian Carrington, Environment, The Guardian, Mar 19, 2025

- Andean glaciers have shrunk more than ever before in the entire Holocene Glaciers are important indicators of climate change. A recent study published in the leading journal Science shows that glaciers in the tropical Andes have now retreated further than at any other time in the entire Holocene. by Stefan Rahmstorf, RealClimate, Mar 19, 2025

- Climate change: Paris Agreement goals still within reach, says UN chief The effects of human-driven climate change surged to alarming levels in 2024, with some consequences likely to be irreversible for centuries - if not millennia – according to a new report from the World Meteorological Organization (WMO). by Staff, Climate & Environment, UN News, Mar 19, 2025

- Rising Seas and Land-Based Salt Pollution Pose Dual Threats for Drinking Water New studies show that climate change is fueling salt contamination in freshwater ecosystems by Kiley Price, Today's Climate, Inside Climate News, Mar 18, 2025

- New Study Reinforces Worries About Pulses of Rapid Sea Level Rise An analysis of peat layers at the bottom of the North Sea shows how fast sea level rose during the end of the last ice age, when Earth was warming at a similar rate as today. by Bob Berwyn, Science, Inside Climate News, Mar 19, 2025

- Wildfire warnings continue in parts of the country as strong winds persist A new cross-country storm will begin to hit the Pacific Northwest on Friday. by Kenton Gewecke & Megan Forrester, ABC News, Mar 21, 2025

- With climate change, cryosphere melt scales up as a threat to planetary health by Sean Mowbray, Momgabay, Mar 21, 2025

Skeptical Science New Research for Week #12 2025

Posted on 20 March 2025 by Doug Bostrom, Marc Kodack

Open access notables

The severe 2020 coral bleaching event in the tropical Atlantic linked to marine heatwaves, Rodrigues et al., Communications Earth & Environment:

Marine heatwaves can amplify the vulnerabilities of regional marine ecosystems and jeopardise local economies and food resources. Here, we show that marine heatwaves in the tropical Atlantic have increased in frequency, intensity, duration, and spatial extent. Marine heatwaves are 5.1 times more frequent and 4.7 times more intense since the records started in 1982, with the 10 most extreme summers/falls in terms of marine heatwave cumulative intensity and spatial extension occurring in the last two decades. The extreme warming during the summer/fall of 2020 led to the largest bleaching event recorded along the Brazilian coast, with 85% of stony corals and 70% of zoanthids areas bleached in Rio do Fogo. The increase in the severity of the marine heatwaves in the western tropical Atlantic is not accompanied by trends in the strength of the local drivers. This suggests that weaker forcing can lead to more devastating marine heatwaves as the global ocean temperature rises due to climate change.

Artificial structures can facilitate rapid coral recovery under climate change, Tanaya et al., Scientific Reports:

Rising seawater temperatures from climate change have caused coral bleaching, risking coral extinction by century’s end. To save corals, reef restoration must occur alongside other climate-change mitigation. Here we show the effectiveness of habitat creation on artificial structures for rapid coral restoration in response to climate change. We use 29 years of field observations for coral distributions on breakwaters and surrounding reefs (around 33,000 measurements in total). Following bleaching in 1998, breakwaters had higher coral cover (mainly Acropora spp.) than did surrounding natural reefs. Coral recovery times on breakwaters matched the frequency of recent bleaching events (~ every 6 years) and were accelerated by surface processing of the artificial structures with grooves. Corals on breakwaters were more abundant in shallow waters, under high light, and on moderately sloped substrate. Coral abundance on breakwaters was increased by incorporating shallow areas and surface texture. Our results suggest that habitat creation on artificial structures can increase coral community resilience against climate change by increasing coral recovery potential.

A new hope or phantom menace? Exploring climate emotions and public support for climate interventions across 30 countries, Baum et al., Risk Analysis:

This article employed a unique, global dataset with 30,284 participants across 30 countries (in 19 languages) to provide insights on 3 questions. We first leveraged the global dataset to map the incidence of fear, hope, anger, sadness, and worry across countries—the first time the climate emotions of adults are investigated on this scale. We also identified significant differences in emotions by level of development, with those in advanced economies reporting weaker levels of climate emotions. Second, using multiple linear regression analyses, we explored the relationship between climate emotions and support for climate-intervention technologies. We determined that the emotions of hope and worry seem to be the most consistently (positively) correlated. Third, we explored if reading about technology categories differentially affected climate emotions. Individuals randomly assigned to read about ecosystems-based CDR [carbon dioxide removal] were significantly more hopeful about climate change (those about SRM [solar radiation management] the least).

Threshold uncertainty, early warning signals and the prevention of dangerous climate change, Hurlstone et al., Royal Society Open Science:

The goal of the Paris Agreement is to keep global temperature rise well below 2°C. In this agreement—and its antecedents negotiated in Copenhagen and Cancun—the fear of crossing a dangerous climate threshold is supposed to serve as the catalyst for cooperation among countries. However, there are deep uncertainties about the location of the threshold for dangerous climate change, and recent evidence indicates this threshold uncertainty is a major impediment to collective action. Early warning signals of approaching climate thresholds are a potential remedy to this threshold uncertainty problem, and initial experimental evidence suggests such early detection systems may improve the prospects of cooperation. Here, we provide a direct experimental assessment of this early warning signal hypothesis. Using a catastrophe avoidance game, we show that large initial—and subsequently unreduced—threshold uncertainty undermines cooperation, consistent with earlier studies. An early warning signal that reduced uncertainty to within 10% (but not 30%) of the threshold value catalysed cooperation and reduced the probability of catastrophe occurring, albeit not reliably so. Our findings suggest early warning signals can trigger action to avoid a dangerous threshold, but additional mechanisms may be required to foster the cooperation needed to ensure the threshold is not breached.

Early warning of complex climate risk with integrated artificial intelligence, Reichstein et al., Nature Communications:

As climate change accelerates, human societies face growing exposure to disasters and stress, highlighting the urgent need for effective early warning systems (EWS). These systems monitor, assess, and communicate risks to support resilience and sustainable development, but challenges remain in hazard forecasting, risk communication, and decision-making. This perspective explores the transformative potential of integrated Artificial Intelligence (AI) modeling. We highlight the role of AI in developing multi-hazard EWSs that integrate Meteorological and Geospatial foundation models (FMs) for impact prediction. A user-centric approach with intuitive interfaces and community feedback is emphasized to improve crisis management. To address climate risk complexity, we advocate for causal AI models to avoid spurious predictions and stress the need for responsible AI practices. We highlight the FATES (Fairness, Accountability, Transparency, Ethics, and Sustainability) principles as essential for equitable and trustworthy AI-based Early Warning Systems for all. We further advocate for decadal EWSs, leveraging climate ensembles and generative methods to enable long-term, spatially resolved forecasts for proactive climate adaptation.

From this week's government/NGO section:

State of the Global Climate 2024, Kennedy et al., World Meteorological Organization

The publication provides a summary of the state of the climate indicators in 2024 with sections on key climate indicators, extreme events, and impacts. The indicators include global temperatures, greenhouse gas concentration, ocean heat content, sea level rise, ocean acidification, Arctic and Antarctic sea ice, glaciers, and precipitation, with an analysis of major drivers of inter-annual climate variability during the year including the El Niño Southern Oscillation and other ocean and atmospheric indices. The highlighted extreme events include those related to tropical cyclones and wind storms; flooding, drought, and extreme heat and cold events. The publication also provides the most recent findings on climate-related risks and impacts including on food security and population displacement.

Meeting the Climate Emergency: University Information Infrastructure for Researching Wicked Problems, Donald Waters, Coalition for Networked Information

The author examines the role of research universities in addressing complex societal challenges. He focuses on climate change, which is best characterized as a “wicked” problem. Such problems are difficult to define and lack clear solutions in part because they involve multiple stakeholders who sometimes have sharply differing interests and perspectives. Given this complexity, understanding climate change is not just a matter for researchers in the STEM fields of science, technology, engineering, and medicine. It requires an all-hands-on-deck approach across the disciplinary spectrum, including experts from the social sciences and humanities. It also requires deep engagement of researchers with the public. The author underscores the urgency and complexity of climate change and other wicked problems that impede human flourishing and offers concrete steps by which universities could adapt their research infrastructure to address these problems more effectively.

107 articles in 51 journals by 664 contributing authors

Physical science of climate change, effects

Amplified wintertime Arctic warming causes Eurasian cooling via nonlinear feedback of suppressed synoptic eddy activities, Yin et al., Science Advances 10.1126/sciadv.adr6336

Fire, Fuel, and Climate Interactions in Temperate Climates, Kampf et al., AGU Advances Open Access 10.1029/2024av001628

Monitoring, modeling, and forecasting long-term changes in coastal seawater quality due to climate change, Guan et al., Nature Communications Open Access 10.1038/s41467-025-57913-4

Climate Fresk - a neat way to make the complexity of climate change less puzzling

Posted on 19 March 2025 by BaerbelW

Up until a few weeks ago, I had never heard of "Climate Fresk" and at a guess, this will also be the case for many of you. I stumbled upon it in the self-service training catalog for employees at the company I work at in Germany where it was announced as a 3-hours workshop called "Klima Puzzle" (Climate Puzzle). Intrigued, I signed up and was one of 7 colleagues to be led through what turned out to be quite an interesting experience. After the workshop, I spend some time browsing the Climate Fresk website and then signed up for a training to become a "Climate Fresker" myself. This allows me to lead people through a Climate Fresk, which I now "only" need to find some time for!

The background story

Climate Fresk encourages the rapid and wide-ranging spread of an understanding of climate issues. The efficiency of the teaching tool, the collaborative experience and the user licence have contributed to the exponential growth of Climate Fresk.

Since its creation, more then 2 million people have participated in a Climate Fresk in 167 countries and 45 languages. More than 90,000 volunteers have been trained to lead a Climate Fresk themselves.

The Climate Fresk game was created by Cédric Ringenbach in 2015 and he has continuously worked on it until it reached its current format. Cédric is an engineer, lecturer and energy transition consultant. A climate change specialist since 2009, he ran The Shift Project between 2010 and 2016. He teaches about energy-climate issues at the “grandes écoles” universities in France (Sup’aéro, Ecoles Centrales, Sciences Po, HEC).

The Climate Fresk NGO was created in December 2018 by Cédric Ringenbach in order to accelerate the spread of the tool, to train and upskill Climate Fresk facilitators who are the international community of Freskers. You can read more about the NGO here.

Sabin 33 #20 - Is offshore wind development harmful to whales and other marine life?

Posted on 18 March 2025 by Ken Rice

On November 1, 2024 we announced the publication of 33 rebuttals based on the report "Rebutting 33 False Claims About Solar, Wind, and Electric Vehicles" written by Matthew Eisenson, Jacob Elkin, Andy Fitch, Matthew Ard, Kaya Sittinger & Samuel Lavine and published by the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia Law School in 2024. Below is the blog post version of rebuttal #20 based on Sabin's report.

When properly sited, offshore wind farms need not pose a serious risk of harm to whales or other marine life. During installation, the impact from construction noise can be mitigated by implementing seasonal restrictions on certain activities that coincide with whale migration. Once operational, wind turbines generate far less low-frequency sound than ships do, and there is no evidence that noise from turbines causes negative impacts to marine species populations (Tougaard et al. 2020).

There has been considerable attention to how offshore wind development, including noise from pile-driving during construction, affects the critically endangered North Atlantic right whale, which has a total population of roughly 360.1 But the main causes of mortality for right whales are vessel strikes (75% of anthropogenic deaths) and entanglements in fishing gear—not anything related to offshore wind development.2 Critically, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has also found no link between offshore wind surveys or development on whale deaths.3

Moreover, any impacts to the North Atlantic right whale can be avoided or greatly minimized through proper planning. For example, in 2019, the developer of the 800-MW Vineyard Wind project entered into an agreement with three environmental organizations, which established seasonal restrictions on pile-driving during construction (to avoid excessive noise when right whales are present), as well as strict limits on vessel speeds during the operational phase (to avoid vessel strikes), among other measures.4 In the final environmental impact statement for the project, the U.S. Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) found that, “[g]iven the implementation of Project-specific measures, BOEM anticipates that vessel strikes as a result of [the project] alone are highly unlikely and that impacts on marine mammal individuals . . . would be expected to be minor; as such, no population-level impacts would be expected.”2 BOEM also found that project installation would be unlikely to cause noise-related impacts to right whales, due to the time of year during which construction activities would take place.2

Offshore wind development can have benefits for other marine species. For example, the base of an offshore wind turbine may function as an artificial reef, creating new habitats for native fish species (Degraer et al. 2020 and here).

By contrast, offshore oil and gas drilling routinely harms marine life, while posing a persistent risk of catastrophic outcomes. Sonar used for offshore oil and gas exploration emits much stronger pulses of sound than sonar used for wind farm surveying. The 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill killed millions of marine animals, including as many as 800,000 birds.5 More broadly, carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuel use are making the ocean increasingly acidic, which inhibits shellfish and corals from developing and maintaining calcium carbonate shells and exoskeletons.6 Finally, climate change is expected to have “long-term, high-consequence impacts” on whales and other marine mammals, including “increased energetic costs associated with altered migration routes, reduction of suitable breeding and/or foraging habitat, and reduced individual fitness, particularly juveniles.”2

Do Americans really want urban sprawl?

Posted on 17 March 2025 by Guest Author

This is a re-post from Yale Climate Connections by Sarah Wesseler

(Image credit: Antonio Huerta)

Growing up in suburban Ohio, I was used to seeing farmland and woods disappear to make room for new subdivisions, strip malls, and big box stores. I didn’t usually welcome the changes, but I assumed others did. If people didn’t want to live in sprawling suburbs, why did I see this kind of development everywhere I went?

But the situation is more complicated than it seems. Although sprawling development is still a familiar sight across the U.S., many experts in urban planning and housing believe this doesn’t occur because of a uniquely American passion for giant parking lots, but as a result of a dysfunctional market. Many people are hungry for denser, more walkable communities, they believe; there just aren’t enough of them to go around.

The question of what kind of communities Americans prefer has important implications for climate change. Suburban U.S. households have substantially higher emissions than their city-center counterparts, largely due to cars. Building more dense, walkable developments could significantly lower these emissions – assuming enough people would both choose to live in such communities and find suitable housing there.

2025 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming News Roundup #11

Posted on 16 March 2025 by BaerbelW, Doug Bostrom, John Hartz

This week's roundup is again published by category and sorted by number of articles included in each. We are still interested in feedback to hone the categorization, so if you spot any clear misses and/or have suggestions for additional categories, please let us know in the comments. Thanks!

Stories we promoted this week, by category and number of articles shared:

Climate Policy and Politics (10 articles)

- `We`re losing our environmental history`: The future of government information under Trump The administration’s wrecking-ball approach has raised profound questions about the integrity and future of vast amounts of information. by Jessica McKenzie, Buelltin of the Atomic Scientists, Mar 05, 2025

- Science, Politics and Anxiety Mix at Rally Under Lincoln Memorial Thousands of protesters gathered in Washington for Stand Up for Science, a rally in response to President Trump’s federal-funding and job cuts by Alan Burdick, Climate, New York Times, Mar 8, 2025

- Energy Secretary Makes Clear Trump 'Ready to Sacrifice' Communities and Climate "As Wright speaks to industry insiders, members of impacted communities, faith leaders, youth, and others are assembling for a 'March for Future Generations,'" one campaigner said of the action at CERAWeek. by Jessica Corbett , Common Dreams, Mar 10, 2025

- NASA fires chief scientist, more Trump cuts to come by AFP, Phys.org, Mar 12, 2025

- EPA considers pulling scientific study that shaped modern climate policy The 2009 scientific finding says carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gas emissions threaten public health by Julia Musto, The Independent News, Mar 12, 2025

- Trump’s ‘drill, baby, drill’ agenda could keep the world hooked on oil and gas The US president is making energy deals with Japan and Ukraine, and in Africa has even touted resurrecting coal by Oliver Milman & Dharna Noor, US News, The Guardian, Mar 12, 2025

- We need NOAA now more than ever by Guest authors: Robert Hart, Kerry Emanuel, & Lance Bosart, RealClimate, Mar 13, 2025

- EPA Freezes, Then Terminates, Multi-Billion Dollar Climate Grants, Scuttling Projects and Triggering Lawsuits The lawsuits could take months, if not years, to resolve, experts say, leaving green banks, clean energy startups and low-income communities in financial limbo. by Aman Azhar, Justice & Health, Inside Climate News, Mar 13, 2025

- Trump moves to close facility that helps track planet-warming pollution The lab is connected to the Mauna Loa Observatory, where scientists gather data to produce the Keeling Curve, a chart on the daily status of atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations. by Scott Dance, Washington Post, Mar 14, 2025

- A foundational climate regulation is under threat Trump’s EPA claims that climate change isn’t a danger to human beings by Umair Irfan , Climate, Vox, Mar 04, 2025

Fact brief - Is waste heat from industrial activity the reason the planet is warming?

Posted on 15 March 2025 by Sue Bin Park

![]() Skeptical Science is partnering with Gigafact to produce fact briefs — bite-sized fact checks of trending claims. You can submit claims you think need checking via the tipline.

Skeptical Science is partnering with Gigafact to produce fact briefs — bite-sized fact checks of trending claims. You can submit claims you think need checking via the tipline.

Is waste heat from industrial activity the reason the planet is warming?

Waste heat’s contribution to global warming is a small fraction of that brought about by carbon dioxide.

Waste heat’s contribution to global warming is a small fraction of that brought about by carbon dioxide.

Waste heat comes from the thermal energy released by human energy use, such as when power plants burn coal or combustion engines burn gasoline.

Dividing the total amount of waste heat by Earth’s surface area, Flanner found about 0.03 Watts per square meter of total warming was from waste heat, about 1%. Carbon dioxide’s greenhouse gas effect added 2.9 Watts per square meter.

Zhang and Caldeira published in 2015 that 1.71% of warming was from the direct heat energy released by fossil fuel combustion, the main source of waste heat.

Carbon dioxide, which makes it more difficult for heat to escape the atmosphere, is the primary driver of climate change. While reducing waste heat is beneficial for efficiency, addressing global warming requires lowering greenhouse gas emissions.

Go to full rebuttal on Skeptical Science or to the fact brief on Gigafact

This fact brief is responsive to quotes such as the one highlighted here.

Sources

Geophysical Research Letters Time scales and ratios of climate forcing due to thermal versus carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuels

Atmospheric Environment Global anthropogenic heat flux database with high spatial resolution

Geophysical Research Letters Integrating anthropogenic heat flux with global climate models

NSF National Center for Atmospheric Research Anthropogenic Heat Flux

Scientific Data Global 1-km present and future hourly anthropogenic heat flux

Skeptical Science New Research for Week #11 2025

Posted on 13 March 2025 by Doug Bostrom, Marc Kodack

Open access notables

Would Adding the Anthropocene to the Geologic Time Scale Matter?, McCarthy et al., AGU Advances:

The extraordinary fossil fuel-driven outburst of consumption and production since the mid-twentieth century has fundamentally altered the way the Earth System works. Although humans have impacted their environment for millennia, justification for a new interval of geologic time lies in the radical shift in the geologic record that marks this “Great Acceleration” of the human enterprise. The rejection of a proposal to define the beginning of the Anthropocene epoch with a “golden spike” in varved sediments from Crawford Lake, Canada, means that we officially we still live in the Holocene, when in practical terms we do not. Formal recognition of the Anthropocene will acknowledge the facts supporting global warming and many other planetary changes that are irreversible on geologic time scales, aligning the Earth Sciences with geologic, planetary and societal reality.

How to stop being surprised by unprecedented weather, Kelder et al., Nature Communications:

We see unprecedented weather causing widespread impacts across the world. In this perspective, we provide an overview of methods that help anticipate unprecedented weather hazards that can contribute to stop being surprised. We then discuss disaster management and climate adaptation practices, their gaps, and how the methods to anticipate unprecedented weather may help build resilience. We stimulate thinking about transformative adaptation as a foundation for long-term resilience to unprecedented weather, supported by incremental adaptation through upgrading existing infrastructure, and reactive adaptation through short-term early action and disaster response. Because in the end, we should take responsibility to build resilience rather than being surprised by unprecedented weather.

Storylines of Unprecedented Extremes in the Southeast United States, Masukwedza et al., Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society:

Disaster planning based on historical events is like driving forward while only looking in the rearview mirror. To expand our field of view, we use a large ensemble of weather simulations to characterize the current risk of extreme weather events in case study locations in the southeastern United States. We find that extreme temperature events have become more frequent between 1981 and 2021, and heavy precipitation events are also more frequent in the wettest months. Combining a historical analysis of people’s recent experience with the rate of change of extreme events, we define four quadrants that apply to groups of case studies: “sitting ducks,” “recent rarity,” “living memory,” and “fading memory.” A critical storyline is that of the sitting ducks: locations where we find a high rate of increase in extreme events and where the most extreme event in recent memory (1981–2021) has a low return period in today’s climate. We find that these locations have a high potential for surprise. For example, in Montgomery County, Alabama, the most extreme temperature event since 1981 has a return period of 13 years in the climate of 2021. In these places, we offer unprecedented synthetic events from the large ensemble for use in disaster preparedness simulations to help people imagine the unprecedented. Our results not only document substantial changes in the risk of extremes in the southeastern United States but also propose a generalizable framework for using large ensembles in disaster preparedness simulations in a changing climate.

Changes to Atmospheric River Related Extremes Over the United States West Coast Under Anthropogenic Warming, Higgins et al., Geophysical Research Letters:

Despite advances in our understanding of changes to severe weather events due to climate change, uncertainty regarding rare extreme events persists. Atmospheric rivers (ARs), which are directly responsible for the majority of precipitation extremes on the US West Coast, are projected to intensify in a warming world. In this study, we utilize two unique large-ensemble climate models to examine rare extreme AR events under various warming scenarios. By quantifying changes to rare extremes, we can gain some insight into the potential for these destructive unprecedented events to occur in the future. Additionally, the abundance of data used in this study enables changes to both seasonal extreme AR occurrences and changes to extremes during various synoptic-scale flow patterns to be explored. From this analysis, we find substantial changes to AR extremes under even mild warming scenarios with disproportionately large changes during weather regimes that are conducive to AR activity.

One-third of the global soybean production failure in 2012 is attributable to climate change, Hamed et al., Communications Earth & Environment:

In 2012, soybean crops failed in the three largest producing regions due to spatially compounded hot and dry weather across North and South America. Here, we present different impact storylines of the 2012 event, calculated by combining a statistical crop model with climate model simulations of 2012 conditions under pre-industrial, present-day (+1 °C), and future (+2 °C) conditions. These simulations use the ECHAM6 climate model and maintain the same observed seasonally evolving atmospheric circulation. Our results demonstrate that anthropogenic warming strongly amplifies the impacts of such a large-scale circulation pattern on global soybean production. Although the drought intensity is similar under different warming levels, larger crop losses are driven not only by warmer temperatures but also by stronger heat-moisture interactions. We estimate that one-third of the global soybean production deficit in 2012 is attributable to anthropogenic climate change. Future warming (+2 °C above pre-industrial) would further exacerbate production deficits by one-half compared to present-day 2012 conditions. This highlights the increasing intensity of global soybean production shocks with warming, requiring urgent adaptation strategies.

Climate-Driven Sea Level Rise Exacerbates Alaskan and Cascadian Tsunami Hazards in Southern California: Implications to Design Parameters, Sepúlveda & Mosqueda, Earth's Future:

Climate-change-driven sea level rise is expected to worsen tsunami hazards in the long term. Tsunami waves will be able to propagate over rising sea levels that will enable them to inundate higher land. In this study, we quantify the increase of tsunami hazards in Southern California due to sea level rise. We consider tsunamis originated in the Alaska and Cascadia subduction zones. Changes of tsunami design parameters, as a result of the sea level rise, are also analyzed. Namely, we analyze the changes of the “maximum considered tsunami” (MCT) elevation, defined as the elevation exceeded with probability 2% in 50 years. We find that earthquakes of the Alaska Subduction Zone constitute the main tsunamigenic contributor. We also find that sea level rise increases MCT tsunami elevations by 0.3 m. With this increase, MCT levels reach 2 m in San Pedro Bay and San Diego. We compare the impact of sea level rise exacerbating tsunami hazards with the impact of common uncertainty sources of tsunami hazard assessment models. The uncertainty of earthquake models, for example, can produce differences in MCT levels that are comparable to the SLR influence.

Greenhouse gases reduce the satellite carrying capacity of low Earth orbit, Parker et al., Nature Sustainability:

Anthropogenic contributions of greenhouse gases in Earth’s atmosphere have been observed to cause cooling and contraction in the thermosphere, which is projected to continue for many decades. This contraction results in a secular reduction in atmospheric mass density where most satellites operate in low Earth orbit. Decreasing density reduces drag on debris objects and extends their lifetime in orbit, posing a persistent collision hazard to other satellites and risking the cascading generation of more debris. This work uses projected CO2 emissions from the shared socio-economic pathways to investigate the impact of greenhouse gas emissions on the satellite carrying capacity of low Earth orbit. The instantaneous Kessler capacity is introduced to compute the maximum number and optimal distribution of characteristic satellites that keep debris populations in stable equilibrium. Modelled CO2 emissions scenarios from years 2000–2100 indicate a potential 50–66% reduction in satellite carrying capacity between the altitudes of 200 and 1,000 km. Considering the recent, rapid expansion in the number of satellites in low Earth orbit, understanding environmental variability and its impact on sustainable operations is necessary to prevent over-exploitation of the region.

From this week's government/NGO section:

Women and girls continue to bear disproportionate impacts of heatwaves in South Sudan that have become a constant threat, Kew et al., World Weather Attribution

Extreme heat has affected a large region of continental eastern Africa since mid-February. Extreme daytime temperatures have been recorded in South Sudan particularly affecting people in poor housing and outdoor workers, a very large part of the population. Scientists from Burkina Faso, Kenya, Uganda, the Netherlands, Germany, Austria, Denmark, Sweden, Mexico, Chile, the United States, and the United Kingdom collaborated to assess to what extent human-induced climate change altered the likelihood and intensity of the extreme heat in the region and to what extent the impacts particularly affected women and girls. When combining the observation-based analysis with climate models, to quantify the role of climate change in this 7-day heat event, the authors find that climate models underestimate the increase in heat found in observations. They can thus only give a conservative estimate of the influence of human-induced climate change. Based on the combined analysis they conclude that climate change made the extreme heat at least 2C hotter and at least 10 times more likely.

The Growing Threat of Catastrophic Flooding in Rural America, Rebecca Anderson and Shannon McNeeley, The Pacific Institute

The frequency and severity of catastrophic flooding events are rising throughout the U.S. and many rural communities are at high risk. Climate change is driving more intense and frequent extreme precipitation events, increasing the likelihood of catastrophic flooding across the U.S. in the future. Rural communities face unique challenges in preparing for and recovering from catastrophic flooding, shaped by factors like geography, social vulnerabilities, and limited resources. Leveraging the extant strengths and assets of rural communities is essential for building resilience and effectively preparing for catastrophic flooding.

170 articles in 66 journals by 1274 contributing authors

Physical science of climate change, effects

A half-century drying in Gobi Oasis, possible role of ENSO and warming/moistening of Northwest China, Li et al., Global and Planetary Change 10.1016/j.gloplacha.2025.104769

Arctic sea-ice loss drives a strong regional atmospheric response over the North Pacific and North Atlantic on decadal scales, Cvijanovic et al., Communications Earth & Environment Open Access 10.1038/s43247-025-02059-w

Climate-Induced Polar Motion: 1900–2100, Kiani Shahvandi & Soja, Geophysical Research Letters Open Access 10.1029/2024gl113405

Distinct Impacts of Increased Atlantic and Pacific Ocean Heat Transport on Arctic Ocean Warming and Sea Ice Decline, Cheng et al., Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans Open Access 10.1029/2024jc021178

Energy Gain Kernel for Climate Feedbacks. Part II: Spatial Pattern of Surface Amplification Factor and Its Dependency on Climate Mean State, Hu et al., Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences 10.1175/jas-d-24-0079.1

Visualizing daily global temperatures

Posted on 12 March 2025 by Zeke Hausfather

This is a re-post from The Climate Brink

Good data visualizations can help make climate change more visceral and understandable. Back in 2016 Ed Hawkins published a “climate spiral” graph that ended up being pretty iconic – it was shown at the opening ceremony of the Olympics that year – and is probably the second most widely seen climate graph after Hawkins’ later climate stripes.

However, I haven’t previously come across any versions of the spiral graph showing daily global temperatures, so I thought it would be fun to create my own (with, I should note, a bit of help from OpenAI’s o3 model to code it).

Here are daily global temperatures by year between 1940 (when the ERA5 daily dataset begins) and the end of 2024, with the color varying from blue to red over time.

Sabin 33 #19 - Are wind turbines a major threat to wildlife?

Posted on 11 March 2025 by Ken Rice

On November 1, 2024 we announced the publication of 33 rebuttals based on the report "Rebutting 33 False Claims About Solar, Wind, and Electric Vehicles" written by Matthew Eisenson, Jacob Elkin, Andy Fitch, Matthew Ard, Kaya Sittinger & Samuel Lavine and published by the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia Law School in 2024. Below is the blog post version of rebuttal #19 based on Sabin's report.

According to the National Audubon Society, two-thirds of all North American bird species are at heightened risk of extinction due to climate change.1 Wildfires will destroy the nesting grounds of many species2, while extreme heatwaves will render their typical habitats uninhabitable.2 For example, the American Goldfinch is projected to lose 65% of its range under a scenario of 3 degrees Celsius global warming, while the Allen’s Hummingbird is projected to lose 64% of its range.2

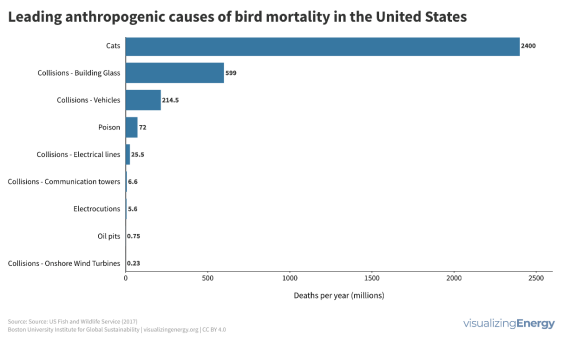

By contrast, wind power is a relatively minor source of mortality for birds. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has estimated that, throughout the United States, cats kill an average of 2.4 billion birds per year, and collisions with building glass kill an average of 599 million birds, while wind turbines kill an average of 234,000 birds per year.3 Collisions with electrical lines cause an average of 25.5 million deaths per year, a number that could grow with the construction of new transmission lines to connect wind projects (and other renewables) to the grid.3 These mortality figures rely on studies dating back to 2013 or 2014 and may be outdated due to the fact that there were fewer wind turbines 10 years ago than there are today.4 However, research has found that wind power causes far fewer bird deaths than fossil fuels per unit of energy output, a metric that is not sensitive to the total number of wind turbines installed. While fossil fuels cause 5.2 avian fatalities per GWh, wind turbines cause only 0.3–0.4 avian fatalities per GWh (Sovacool 2013).5

Figure 1: Leading anthropogenic causes of deaths to birds in the United States. Source: Boston University Institute for Global Sustainability.6

The impacts of wind development on certain bat species may be more severe. One study published in 2021 estimated that the population of hoary bats in North America could decline by 50% by 2028 without adoption of measures to reduce fatalities (Friedenberg & Frick 2021).

However, actionable steps can be taken to reduce bird and bat fatalities from wind turbines. With respect to birds, most deaths occur when turbines are sited near nesting places. Siting facilities to avoid where birds nest, feed and mate, as well as where they stop when migrating, has proved successful at reducing fatalities.5 In addition, the wind turbine components that pose the greatest risk to birds are the blades and tower. The relatively simple action of painting the tower black has been shown to reduce deaths of ptarmigans (a bird in the grouse family) by roughly 48% (Stokke et al. 2020), while painting one of the blades black has reduced deaths by 70% (May et al. 2020).7 Other successful methods include slowing or stopping turbine motors when vulnerable species are present, in order to reduce the likelihood of collisions.8 Deployment of this method in Wyoming has contributed to an 80% decline in eagle fatalities (McLure et al. 2021). With respect to bats, strategies to minimize fatalities include curtailment (i.e., stopping wind turbines from spinning under certain circumstances), as well as ultrasonic acoustic deterrents (Friedenberg & Frick 2021) and visual deterrents.9 In 2022, the U.S. Department of Energy awarded $7.5 million in research grants to study bat deterrent technologies.10

Overall, though it remains difficult to eliminate the risk of collisions entirely, wind power can ultimately help to protect bird and bat populations by displacing fossil fuels and mitigating climate change impacts.11

Arguments

Arguments