The Debunking Handbook Part 2: The Familiarity Backfire Effect

Posted on 18 November 2011 by John Cook, Stephan Lewandowsky

Update Oct. 14, 2020:

Update Oct. 14, 2020:

The Debunking Handbook is now available in an extensively updated version written by Stephan Lewandowsky, John Cook, Ulrich Ecker and 19 co-authors. Read about this new edition in this blog post: The Debunking Handbook 2020: Downloads and Translations

Excerpt 3 from this new edition of The Debunking Handbook explains the latest research about The elusive backfire effects.

Please scroll down for an update posted on June 22, 2017 regarding The Familiarity Backfire Effect!

For the most current information about this elusive effect please read the relevant excerpt from the new version of the handbook here.

The Debunking Handbook is a freely available guide to debunking myths, by John Cook and Stephan Lewandowsky. Although there is a great deal of psychological research on misinformation, unfortunately there is no summary of the literature that offers practical guidelines on the most effective ways of reducing the influence of misinformation. This Handbook boils down the research into a short, simple summary, intended as a guide for communicators in all areas (not just climate) who encounter misinformation. The Handbook will be available as a free, downloadable PDF at the end of this 6-part blog series.

This post has been cross-posted at Shaping Tomorrow's World.

To debunk a myth, you often have to mention it - otherwise, how will people know what you’re talking about? However, this makes people more familiar with the myth and hence more likely to accept it as true. Does this mean debunking a myth might actually reinforce it in people’s minds?

To test for this backfire effect, people were shown a flyer that debunked common myths about flu vaccines.1 Afterwards, they were asked to separate the myths from the facts. When asked immediately after reading the flyer, people successfully identified the myths. However, when queried 30 minutes after reading the flyer, some people actually scored worse after reading the flyer. The debunking reinforced the myths.

To test for this backfire effect, people were shown a flyer that debunked common myths about flu vaccines.1 Afterwards, they were asked to separate the myths from the facts. When asked immediately after reading the flyer, people successfully identified the myths. However, when queried 30 minutes after reading the flyer, some people actually scored worse after reading the flyer. The debunking reinforced the myths.

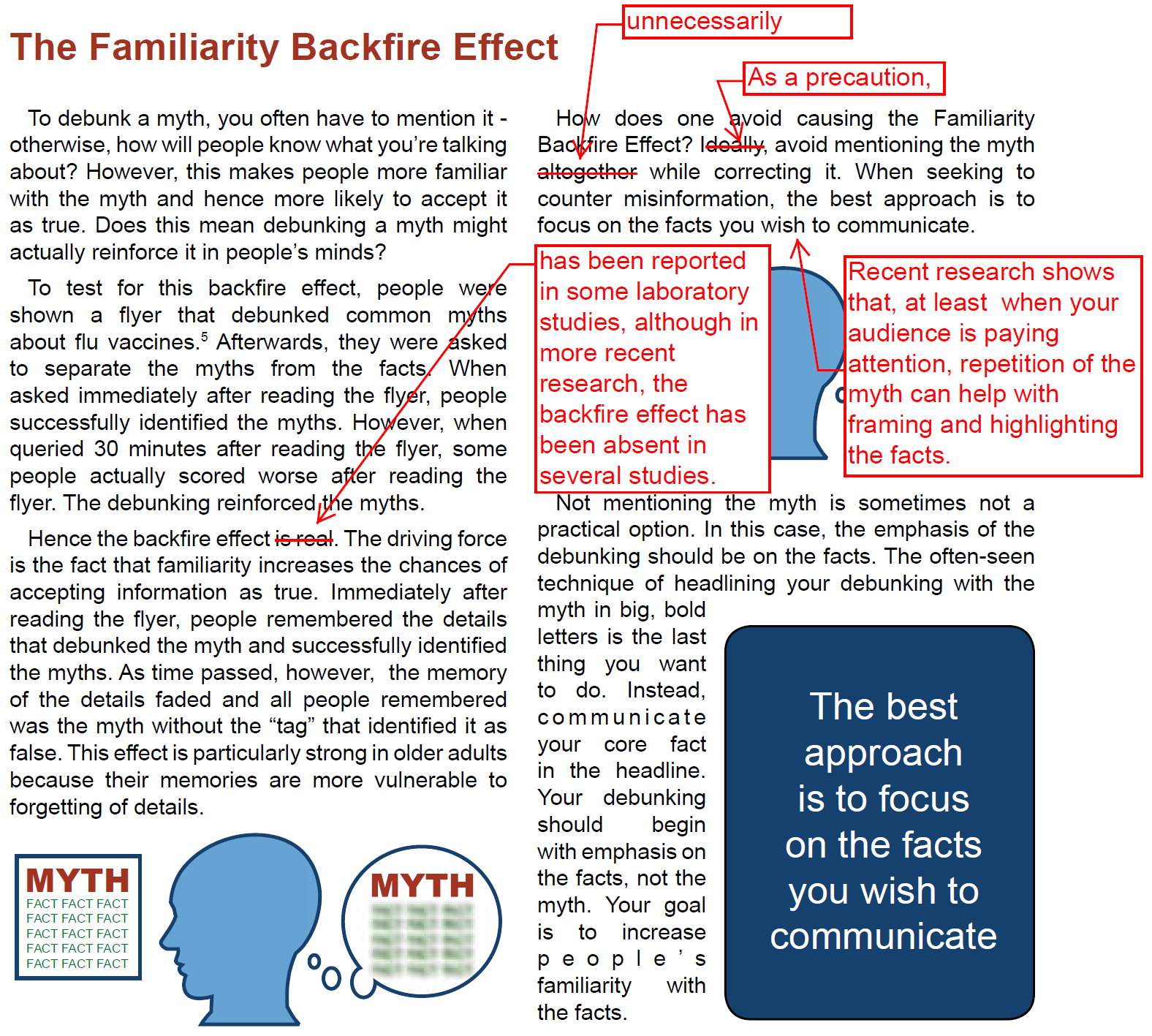

Hence the backfire effect is real. The driving force is the fact that familiarity increases the chances of accepting information as true. Immediately after reading the flyer, people remembered the details that debunked the myth and successfully identified the myths. As time passed, however, the memory of the details faded and all people remembered was the myth without the “tag” that identified it as false. This effect is particularly strong in older adults because their memories are more vulnerable to forgetting of details.

How does one avoid causing the Familiarity Backfire Effect? Ideally, avoid mentioning the myth altogether while correcting it. When seeking to counter misinformation, the best approach is to focus on the facts you wish to communicate.

Not mentioning the myth is sometimes not a practical option. In this case, the emphasis of the debunking should be on the facts. The often-seen technique of headlining your debunking with the myth in big, bold letters is the last thing you want to do. Instead, communicate your core fact in the headline. Your debunking should begin with emphasis on the facts, not the myth. Your goal is to increase people’s familiarity with the facts.

Update June 2017: Some news about The Familiarity Backfire Effect

Stephan Lewandowsky published the post Claiming that Listerine alleviates cold symptoms is false: To repeat or not to repeat the myth during debunking? on June 22 which contains this annotated screenshot from the handbook:

You can read more about this latest research in a series of three blog posts on Shaping Tomorrow's World:

- Can Repeating False Information Help People Remember True Information? - published on June 19, 2017 by Tania Lombrozo

- Qualifying the Familiarity Backfire Effect - published on June 20, 2017 by Briony Swire

- Familiarity-based processing in the continued influence of misinformation - published on June 21, 2017 by Stephan Lewandowsk

References

- Skurnik, I., Yoon, C., Park, D., & Schwarz, N. (2005). How warnings about false claims become recommendations. Journal of Consumer Research, 31, 713-724.

Arguments

Arguments

[DB] "When educated people try to explain facts with a story to show others how inteligent they are the"

Umm, no. Educated people try to explain facts with a story to show others because they are trying to help others learn. You are projecting your perception of things onto others here.

"A bit like what you said makes no sence just noise to me"

If you do not understand the explanation, ask for a different one instead of pointing fingers.

"Science shouldn't be a foreign language When communicating to the public."

That is the entirety of why we donate our time here: to try and help communicate climate science to the public in clear, understandable words.

[JC] Welcome also from me :-) Our treatment of the Familiarity Backfire Effect is deliberately quite brief and simplified in the Debunking Handbook - our aim is to provide a short, practical guide. I am also working with Stephan Lewandowsky and a few other scientists (including your co-author Norbert Schwarz) on a more thorough, scholarly review of research into misinformation.