Big Oil and the Demise of Crude Climate Change Denial

Posted on 26 October 2012 by Andy Skuce

From 1989 to 2002, several large US companies, including the oil companies Exxon and the US subsidiaries of Shell and BP, sponsored a lobbying organisation called the Global Climate Coalition (GCC), to counter the strengthening consensus that human carbon dioxide emissions posed a serious threat to the Earth’s climate. As has been documented by Hoggan and Littlemore and Oreskes and Conway, the GCC and its fellow travellers took a leaf out of the tobacco industry’s playbook and attempted to counter the message of peer-reviewed science by deliberately sowing doubt through emphasizing uncertainties and unknowns. The climate scientist Benjamin Santer accused the GCC of deliberately suppressing scientific information that supported the IPCC consensus.

In the late 1990s, the oil industry’s response to the climate question started to change, when BP and Shell decided to abandon the GCC and instead embrace the scientific consensus. According to the account by ex-BP geologist Bryan Lovell in his book Challenged by Carbon, BP’s change of mind was triggered by a memo sent in 1997, by then Chief Geologist David Jenkins, to the managing directors of the company that maintained that it was time for BP to be prepared to respond to the climate crisis in a constructive manner. Jenkins’ argument—which is detailed in Lovell’s book—was framed to appeal to BP’s corporate self-interest; pointing to future opportunities to employ the company’s subsurface expertise for carbon sequestration, and also to shift the climate mitigation focus away from the oil industry onto the coal-fired power sector. (Experienced corporate insiders know that appeals to ethics gain less traction than appeals to self-interest.) Jenkins’ recommendation was well received and over the following years the company changed its name to “BP plc”, changed to a new sunflower logo (at a cost of $211 million) and adopted the slogan “Beyond Petroleum”. In 2002, the chief executive of BP, Lord John Browne gave a speech in which he said:

''Climate change is an issue which raises fundamental questions about the relationship between companies and society as a whole, and between one generation and the next.''

and

''Companies composed of highly skilled and trained people can't live in denial of mounting evidence gathered by hundreds of the most reputable scientists in the world.''

Not every big oil company responded as deftly. Exxon, under the leadership of CEO Lee Raymond, remained a sponsor of several climate-change-skeptic organizations until the mid-2000s. In 2006, Raymond was replaced by Rex Tillerson, who took a more enlightened view, accepting the scientific consensus. However, recently Tillerson has downplayed the global warming threat, claiming that it is just an engineering problem with engineering solutions and assuring us that no matter how bad things get, “we’ll adapt to that”.

The recent PBS documentary Climate of Doubt showed how Exxon was motivated into its new strategy on climate science, not so much out of virtue, but out of corporate self-interest as a result of pressure from activist shareholders and threats of customer boycotts.

Big Oil on emissions and climate change in 2012

Below are some quotes from the big four oil companies’ websites:

Exxon: "Rising greenhouse gas emissions pose significant risks to society and ecosystems."

Shell: "…CO2 emissions must be reduced to avoid serious climate change. To manage CO2, governments and industry must work together. Government action is needed and we support an international framework that puts a price on CO2, encouraging the use of all CO2-reducing technologies."

BP: "According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), warming of the climate system is happening and is caused mainly by the increase in greenhouse gas emissions and the increasing concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. Results from models assessed by the IPCC suggest that to stand a reasonable chance of limiting warming to no more than 2?C, global emissions should peak before 2020 and be cut by between 50-85% by 2050."

Chevron: "At Chevron, we recognize and share the concerns of governments and the public about climate change. The use of fossil fuels to meet the world's energy needs is a contributor to an increase in greenhouse gases (GHGs)—mainly carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane—in the Earth's atmosphere. There is a widespread view that this increase is leading to climate change, with adverse effects on the environment."

These companies no longer easily fit the stereotype of “Merchants of Doubt”, at least when it comes to the basic science of climate change. The denizens of "skeptic" climate blogs and the majority of Republican Party politicians will find little in the way of support for their anti-consensus views on the climate webpages of the big oil companies. Nevertheless, the damage done to the public perception of climate science by the GCC and other oil-company-sponsored organizations lingers on.

The Four Sisters’ Big Brothers

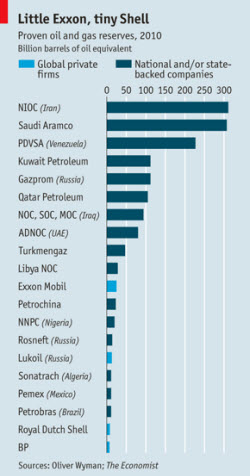

In the 1950s and up to the mid-1970s, seven big international oil companies (IOCs), known as the Seven Sisters (who have since merged into the four companies Exxon, BP, Shell and Chevron), controlled about 85% of the world’s oil reserves. No longer. The National Oil Companies (NOCs) now control 55% of the world’s production, 88% of the reserves and the IOC’s today have full access to only 15% of the world’s reserves (see this EIA report for details). The “Big Oil” oligopoly is over. Today’s world oil business is run by governments, and not usually by democratic ones.

Despite this, all of these Really Big Oil governments participate in the Inter-governmental Panel on Climate Change and none of them publicly dispute the science.

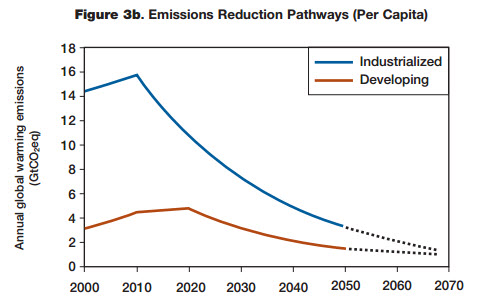

However, when it comes to the scale of reductions needed to avoid dangerous climate change, the fact is that the oil industry will have to go into a production decline very shortly and fossil fuel production will have to shrink dramatically by mid-century, especially in industrialized countries where the IOCs make most of their sales.

Source: The Economist

Per-capita emissions pathways to achieve a 450 ppm CO2 equivalent stabilization target. From the Union of Concerned Scientists (2007).

Such a huge reduction in consumption would price high-production-cost oil (e.g., deep water, Arctic, tight oil) out of the shrinking market. The future reduction in demand would have to be achieved by some kind of carbon pricing, so that the high-carbon-emission oils such as the Alberta oil sands would be preferentially squeezed out as well. IOC’s today are increasingly focussing on high-operating cost, carbon-intensive oils marketed to industrialized nations. The world in 2050 will not be a big enough place to accommodate both a thriving oil industry and a stable climate.

How did oil producers come to accept scientific reality so easily?

Surveys show that a significant fraction of the American public still rejects the scientific consensus on human-caused global warming, and that the issue is considered to be so divisive in the United States that it has barely received a mention in the 2012 Presidential elections. On the basis of my own involvement in the climate debate, it seems fair to conclude that individuals who reject human-caused climate change tend to be stubborn in their beliefs and it is a rare occurrence when somebody admits that they have changed their minds due to the mounting evidence. In contrast, oil-producing corporations and countries seem to have embraced the scientific consensus quite readily, even though their current business models are incompatible with the emissions cutbacks that will be required for mitigation. How can we explain that the big IOCs were able to change their minds, while many other climate “skeptics” remain obstinately impervious to persuasion?

I propose that the reason for this is because individuals tend to come by their beliefs through intuitive, emotional responses (Daniel Kahneman’s fast brain), which they then use their reason (slow brain) to justify after the fact. Furthermore, they then stick to these beliefs, partly as a matter of solidarity with their cultural group, regardless of how much more they learn about the science. Countries and corporations, on the other hand (paraphrasing Charles de Gaulle), don’t have friends or emotions; they only have interests. A corporation’s key interest in a competitive market is to maintain the confidence of its shareholders, customers and employees, a goal that the IOCs evidently—judging from Lord Browne’s speech quoted earlier—considered to be incompatible with a transparently self-serving tactical rejection of the consensus of scientific experts.

And it’s not just hot air. Oil companies don’t just say that they accept climate change; they are acting as if it is really happening, especially with their plans to explore in the Arctic. For example, Shell’s Environmental Assessment report for plans to drill in the Chuckchi Sea, Alaska, acknowledges the work of the IPCC and makes several references to the lengthening open water season in the Arctic Ocean. If any contrarian truly believes that the Arctic sea ice retreat that we have seen in recent years is part of a decadal cycle, then there is good money to be made shorting the stock of the oil companies who are making big bets on the sea ice disappearing for ever.

A muddled verdict on Big Oil and climate change

Even though big oil companies are, for the most part, no longer actively questioning the fundamentals of climate science, they are spending millions in the 2012 presidential elections in the USA to support politicians perceived as more inclined to approve projects such as the Keystone XL pipeline and more ready to reduce regulatory burdens and allow more drilling on federal lands. A 2012 report from the Union of Concerned Scientists describes how the public relations messages on climate change issued by corporations are often contradicted by the corporations’ actions.

Perhaps surprisingly, many oil companies support a carbon tax. In some cases this may be companies seeking a way to favour gas production over more carbon-intensive coal, but some oil sands companies support a carbon tax as well. The reason for this is because corporations are very keen to reduce uncertainty, especially when it comes to long-term capital intensive projects. They would prefer to know the rules now and then decide what to invest in, rather than invest now and discover later that their project is no longer economic due to taxation changes. More details on this can be found in a report by the Sustainable Prosperity think tank.

Although some of the oil company climate action statements may appear to the cynical to be mere greenwash (i.e., PR promises devoid of content), some actions have produced real results, notably efforts to reduce methane leakage. A recent paper in Nature by Simpson et al (2012) (paywalled but see also the article in Climate Central) linked observed declines in atmospheric ethane to reduced fugitive emissions of methane (and associated ethane) from oil and gas operations. Simpson and her colleagues estimate that this may have reduced methane emissions by 10-21 Tg/yr (million tonnes per year), and that this could account for 30-70% of the total decline in methane emissions since 1984. If true, this would be the only climate mitigation action ever to have shown results detectable at the Mauna Loa Observatory. On the other hand, atmospheric methane concentrations have recently started to climb again, perhaps due to recent increased rates of shale gas drilling.

Nobody should be under the illusion that oil companies are going to lead the fight against climate change. The actions required to deal with the climate crisis will mean rendering obsolete the core competencies and assets of fossil fuel corporations and it would be folly to expect these (figurative) turkeys to vote for Christmas. (See Bill McKibben’s article Global Warming’s Terrifying New Math and the Carbon Tracker report.) We should, however, acknowledge that the companies no longer actively oppose the science and, for the most part, have stopped directly funding the groups that do. That’s probably the best that climate activists can hope for from commercial organizations whose business is in extracting hydrocarbons fuels from the Earth so that their customers can burn them and dispose of the waste into the atmosphere.

But there’s also an important lesson here for those individuals who persist in rejecting or downplaying the consensus on climate change: if the big oil companies can suck it up and face scientific reality, why can’t you?

Arguments

Arguments

0

0  0

0

Comments