The economic impacts of carbon pricing

What the science says...

| Select a level... |

Basic

Basic

|

Intermediate

Intermediate

|

Advanced

Advanced

| ||||

|

Climate economics research shows that in reality, we are harming the economy by failing to implement CO2 limits. |

|||||||

CO2 limits will harm the economy

"Legally mandated measures for reducing greenhouse gas emissions are likely to have significant adverse impacts on GDP growth of developing countries [...] This in turn will have serious implications for our poverty alleviation programs." (Pradipto Ghosh)

When you start talking about economics, the eyes of many a climate science geek (present company included) begin to glaze over. However, this is a critical subject. When you ask a climate contrarian why they won't support climate action just in case they are wrong, the contrarians will invariably assert that pricing and reducing carbon emissions will harm the economy. However, this assertion is in direct contradiction with the body of climate economics literature, which actually shows the opposite is true.

For example, a new paper by Johnson & Hope 2012 evaluates the overall cost of carbon emissions via climate change damages, and finds that when these costs are taken into consideration:

- current estimates of the overall costs of carbon emissions (via damage from climate change) are generally too low

- when those costs are taken into account, solar energy is already cheaper than coal, and wind is probably cheaper than natural gas

- by failing to put a price on and reduce carbon emissions, and by continuing to rely on fossil fuels, we are damaging the economy

The social cost of carbon (SCC) is effectively an estimate of the direct effects of carbon emissions on the economy - it estimates how much damage our emissions cause via climate change, or how much it will cost us to adapt to climate change. The SCC takes into consideration such factors as net agricultural productivity loss, human health effects, property damages from sea level rise, and changes in ecosystem services.

The SCC is a difficult number to estimate, but is key to any cost-benefit analysis of climate legislation. The main argument against putting a price on carbon emissions is that doing so will harm the economy. The only way to evaluate this assertion is to compare the costs of carbon pricing to the benefits (the avoided costs from climate change damage), and the benefits are measured via the SCC.

Johnson & Hope 2012 (JH12) notes that the U.S. Interagency Working Group on the Social Cost of Carbon (hereinafter "Working Group") published its first SCC estimates in 2010, with a central value of $21 per metric ton of CO2, suggesting that economic analyses also be performed for SCC values of $5, $35, and $65. JH12 note that these figures have been criticized as too conservative for several reasons.

"These estimates have been criticized for relying upon discount rates that are considered too high for intergenerational cost–benefit analysis, and for treating monetized damages equivalently between regions, without regard to income levels."

JH12 re-estimate the SCC values using a range of discount rates and methodologies they consider more appropriate for the very long time horizons associated with climate change. As a result, they estimate the SCC is several times higher than the Working Group estimate.

Equity Weights

JH12 note that the Working Group approach did not assign “equity weights” to damages based upon relative income levels between regions. In this approach, a dollar’s worth of damages occurring in a poor region is given more weight than one occurring in a wealthy region. This is because as JH12 note,

"poorer regions are expected to have far less income to cope with damages than are wealthier regions, a problem compounded by the fact that they are also expected to bear more of the damages while having contributed the least to the problem"

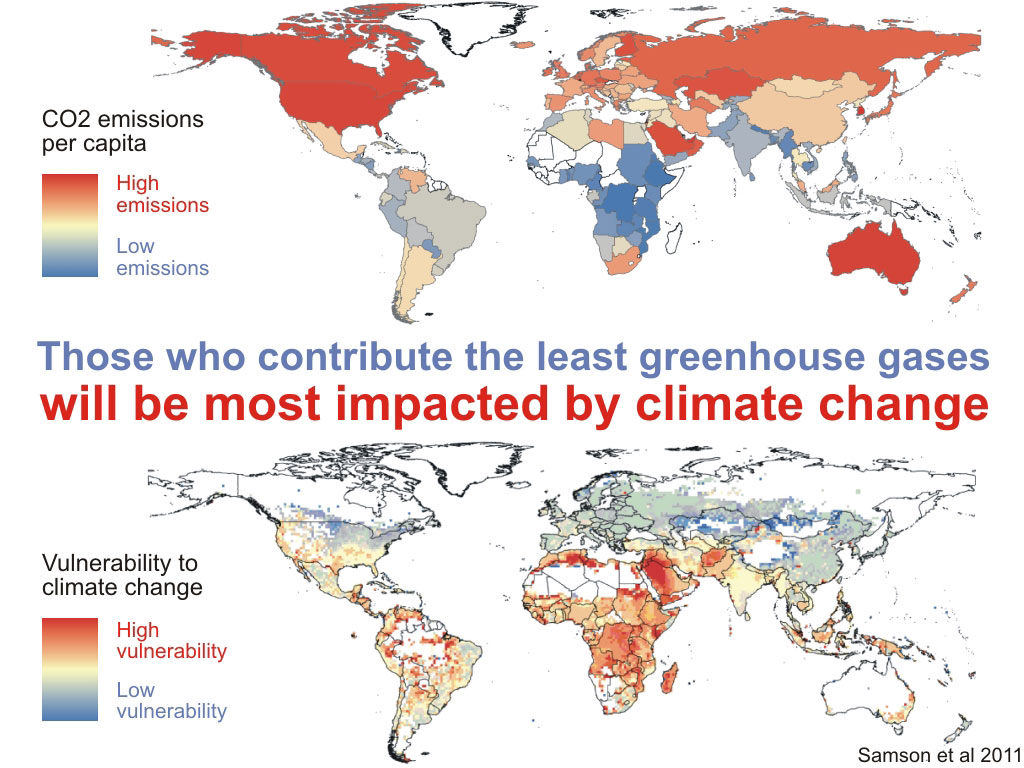

That poorer regions are expected to be the most impacted by climate change was demonstrated by Samson et al. 2011 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Per capita emissions vs. vulnerability to climate change, from Samson et al. (2011)

In their paper, JH12 do apply equity weights in their SCC calculations.

Discount Rates and Roberts Otters

The term 'discount rate' refers to the time value of money - how much more a dollar is worth to us today than next year, related to interest rates. A high discount rate means we would much rather have money today than in the future.

This is a key variable in determining the proper SCC. The costs of emissions reductions are primarily incurred in the short-term, whereas the economic benefits of emissions reductions (the avoided costs from climate change damage) mainly occur in the future. Thus if we say a dollar is worth much more now than in 30 years, emissions reductions costs are weighted much more heavily than the benefits of avoided climate damage, resulting in a lower SCC.

For example, JH12 note that 25 years from now, for a 5% annual discount rate, $100 worth of climate damage has a present value of only $30 ($100/[1.0525]), due to the effect of compound interest. The present value of $100 worth of damage falls to 76 cents 100 years in the future if using a 5% discount rate. Thus the lowest SCC estimates, for example from economists Richard Tol and William Nordhaus, tend to result from assuming very high discount rates (3 to 5%).

There are two main justifications for using a high discount rate - the assumption that future generations will be wealthier than today's (and their increased wealth will more than offset the costs of climate change), and the opportunity cost of foregone investments (money spent reducing emissions could have been invested elsewhere).

JH12 criticize the Working Group for selecting relatively high discount rates. The Working Group used 2.5%, 3%, and 5% (recommending 3% for estimating the SCC central value), based on current market interest rates, which they argued avoids the need for imposing subjective values. But that's a problem because climate change has costs that are difficult to quantify economically - for example the value of human life, and thus the cost of people dying of starvation if there is insufficient food as a result of agricultural damage from climate change. Using a 3% discount rate completely neglects the "subjective" cost of human suffering and human life.

JH12 also argue that the Working Group did not consider the full range of consumption interest rates observed in markets, nor intergenerational discount rates established in the economics literature and recognized in government guidelines. They note that in a 2008 technical support document, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) suggested a discount rate between 0.5% and 3%, noting:

"A review of the literature indicates that rates of three percent or lower are more consistent with conditions associated with long-run uncertainty in economic growth and interest rates, intergenerational considerations, and the risk of high impact climate damages (which could reduce or reverse economic growth)"

As discussed above, one of the main justifications for using a high interest rate is the assumption that future generations will be wealthier. However, as the EPA notes here, major climate impact damages could prevent that from happening, if we have to devote major financial resources to adapting to climate costs.

As one counter-example to the Working Group, the Stern Review for the British government used a 1.4% discount rate. There are many other reasons for using a lower discount rate, for example the fact that money isn't everything, and as noted above we also need to consider the climate-related suffering of future generations. Dave Roberts has a good discussion of discount rates along with photos of otters to keep your interest, since this isn't the most enthralling subject to read about.

In their study, JH12 use discount rates of 1%, 1.5%, and 2%, and compare their results to those in the Working Group's analysis with higher discount rates.

What is the Appropriate Discount Rate?

So JH12 argue for a discount rate between 1% and 2%, whereas the Working Group used 2.5% to 5%, the Stern Review used 1.4%, and more conservative economists use 3% to 5%. But which is right?

Well, the answer is somewhat subjective, which is why the Working Group decided to try and remove subjectivity and simply choose conservative market-based values. But as discussed above, there is a very strong case for lower discount rate values. What if we split the difference?

Weitzman (2007) in discussing the Stern Review notes that for interest and discount rates, splitting the difference is mathematically not the same as taking the average. In his terminology, "r" is the interest rate (emphasis added):

"A chance of r = 6 percent and a chance of r = 1.4 percent are not at all the same thing as splitting the difference by selecting the average r = 3.7 percent. It is not discount rates that need to be averaged but discount factors. A chance of a discount factor of e−6 a century hence and a chance of a discount factor of e−1.4 a century hence make an expected discount factor of 0.5e−6 + 0.5e−1.4 a century hence, which, when you do the math, is equivalent to an effective interest rate of r = 2 percent...with the above numbers it is a lot closer to the Stern value and is not anywhere near the arithmetic average of r = 3.7 percent."

So this also strenghthens the case for using discount rate and SCC values in the JH12 range. We should note that Weitzman (2007) ultimately argued for discount rates in the 2–4% range, as opposed to the 6–7% range. However, now that we are considering discount rates in the 1–5% range, splitting the difference would result in a discount rate of ~1.7%.

Results and their Importance

JH12 find central SCC values of $266, $122, and $62 per metric ton of CO2 using discount rates of 1%, 1.5%, and 2%, respectively. They also estimated SCC using declining discount rate schedules (UK Green Book and Weitzman), finding central values of $55 and $175 per metric ton of CO2, respectively. These central SCC values exceed the Working Group central value by factors of 2.6 to 12.7.

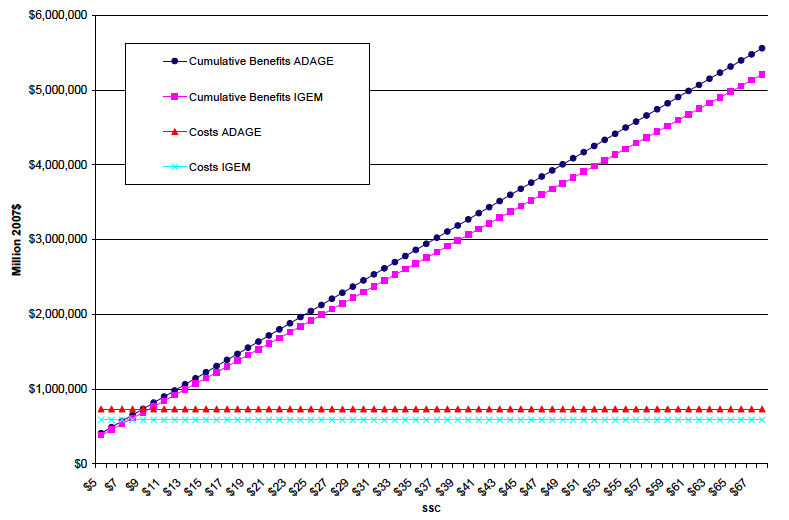

So what does this mean? Well, the break-even point between carbon emissions reductions' costs and benefits is estimated at around $5-10 per ton of CO2 (Figure 2), meaning that if the real-world cost of carbon emissions exceeds $9 per ton, the benefits of carbon pricing will exceed the costs.

$9 per ton is essentially the lowest possible value for SCC, if we use a very high discount rate of 5%. Using more justifiable discount rates, SCC is between $55 and $266 per ton of CO2. In other words, the benefits of reducing CO2 emissions far outweigh the economic costs.

Figure 2: Costs (light blue and red points) and Benefits (dark blue and purple points) vs. SCC values ($ per ton of carbon dioxide) using two economic models (ADAGE and IGEM), from New York University School of Law's Institute for Policy Integrity. Note the x-axis label contains a typo - SSC should read SCC.

Note that even exceptionally conservative economists like William Nordhaus - whose SCC central estimate is only around $9 per ton of CO2 (in current dollars) - argue that carbon emissions reductions will benefit the economy. Nordhaus has frequently been cited by climate contrarians, and his work misrepresented to argue against reducing emissions. Nordhaus recently decided to set the record straight:

"My research shows that there are indeed substantial net benefits from acting now rather than waiting fifty years [to reduce CO2 emissions]...the loss from waiting is $4.1 trillion."

And remember, those results are based on an SCC of around $9 per ton of CO2 emitted, whereas JH12 argue that more appropriate discount rates put SCC between $55 and $266 per ton. There is simply no question that putting a price on carbon emissions will result in a net savings and benefit the economy, even under the most conservative estimates.

Which Energy Sources are Actually Cheapest?

A frequent argument from opponents to emissions reductions and carbon pricing, for example John Christy, is that "cheap" fossil fuel energy is key to the development of poorer nations. However, in claiming that fossil fuels are cheap, this argument neglects the climate impacts from associated greenhouse gas emissions - the SCC (not to mention neglecting the fact that poorer nations tend to be most impacted by climate change, as illustrated in Figure 1).

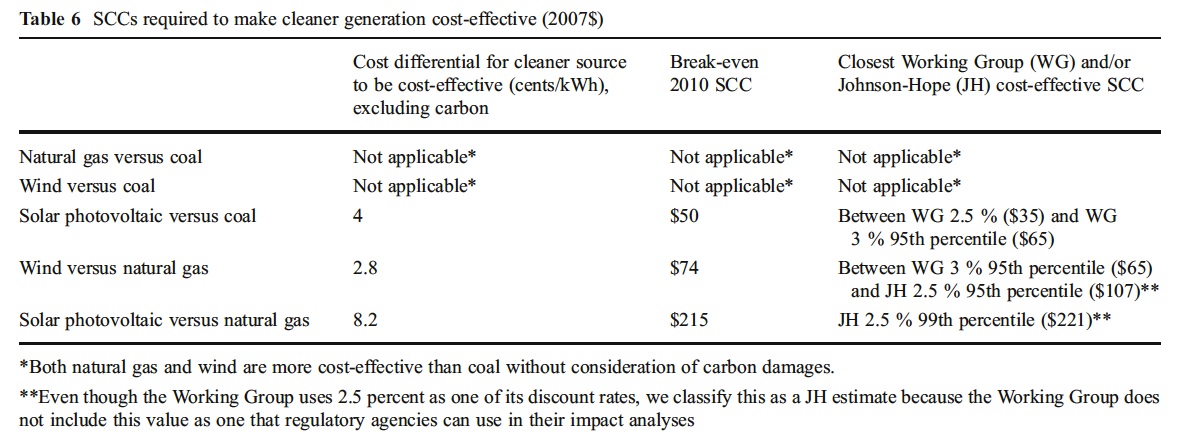

This raises an important question - when we include the SCC, which energy sources are actually the cheapest? JH12 examine this question for coal, natural gas, wind, and solar photovoltaic (PV) energy technologies (Table 6), with some caveats that their break-even SCC values are conservative.

"New natural gas and wind are competitive over new coal absent any pollution costs, and therefore no SCC is required to make them cost-effective. An SCC...of $50, would justify building solar photovoltaic over coal...An SCC of $215 would justify solar over natural gas....Wind would require an SCC of $74 to be cost-effective over natural gas."

"The break-even SCCs presented here are conservative in three respects. First, the SCC grows over time, whereas the SCCs used here are for 2010. Accounting for the growth of SCCs over time would increase the cost of generation (inclusive of carbon damages) with coal or gas for a given starting SCC, reducing the 2010 SCC that corresponds to break even generation costs. Second, technological innovation may continue to drive down costs of wind and solar in the future, further lowering the break-even SCC. Third, we do not account for externalities other than air emissions from the power plants, such as methane emissions from natural gas wells and land disturbance from coal mining."

According to their results, solar PV energy is already cheaper than coal if we use a discount rate of 2%, and the price of solar PV technology is also falling rapidly. Wind energy is also cheaper than natural gas if we use a discount rate between 1.5% and 2%, and solar PV is cheaper than natural gas for a discount rate between 1% and 1.5%.

Summary

There are several very important points we can take from this research.

- The current range of SCC values used by the U.S. government is too conservative. An appropriate central estimate would be around $100 per ton of CO2, with a range between $21 and $266 per ton.

- This central estimate exceeds the break-even point between carbon emissions reductions costs and benefits ($5-10 per ton) by an order of magnitude. The break-even point also falls below the range of appropriate SCC values ($21 to $266 per ton). This means we can be very confident that reducing carbon emissions will result in a net economic benefit.

- Even the most conservative economists agree that reducing carbon emissions will result in a net economic benefit.

- Solar PV energy is probably already cheaper than coal energy, and wind is probably cheaper than natural gas, when carbon emissions costs are considered.

- Overall, by failing to put a price on and reduce carbon emissions, and by continuing to rely on fossil fuels, we are damaging the economy. Those who argue the converse are failing to account for the costs of damage caused by climate change.

It's also worth noting that a new report from the Congressional Research Service concluded that a much more modest carbon tax of $20 per ton of CO2 - on the very low end of the appropriate SCC range - could cut the projected 10-year deficit in the USA by 50 percent, from $2.3 trillion down to $1.1 trillion. Another new report by the DARA group and the Climate Vulnerable Forum, written by more than 50 scientists, economists and policy experts, and commissioned by 20 governments estimates that climate change is already contributing to the deaths of nearly 400,000 people a year and costing the world more than $1.2 trillion annually, wiping 1.6% from global Gross Domestic Product every year. So the costs of failing to price carbon and reduce emissions are already very real.

Last updated on 29 September 2012 by dana1981. View Archives

Arguments

Arguments

Climate Myth...