How extreme was the Earth's temperature in 2023

Posted on 17 April 2024 by Guest Author

This is a re-post from Andrew Dessler at the Climate Brink blog

In 2023, the Earth reached temperature levels unprecedented in modern times. Given that, it’s reasonable to ask: What’s going on? There’s been lots of discussions by scientists about whether this is just the normal progression of global warming or if something we don’t understand is happening — in other words, we’ve broken the climate.

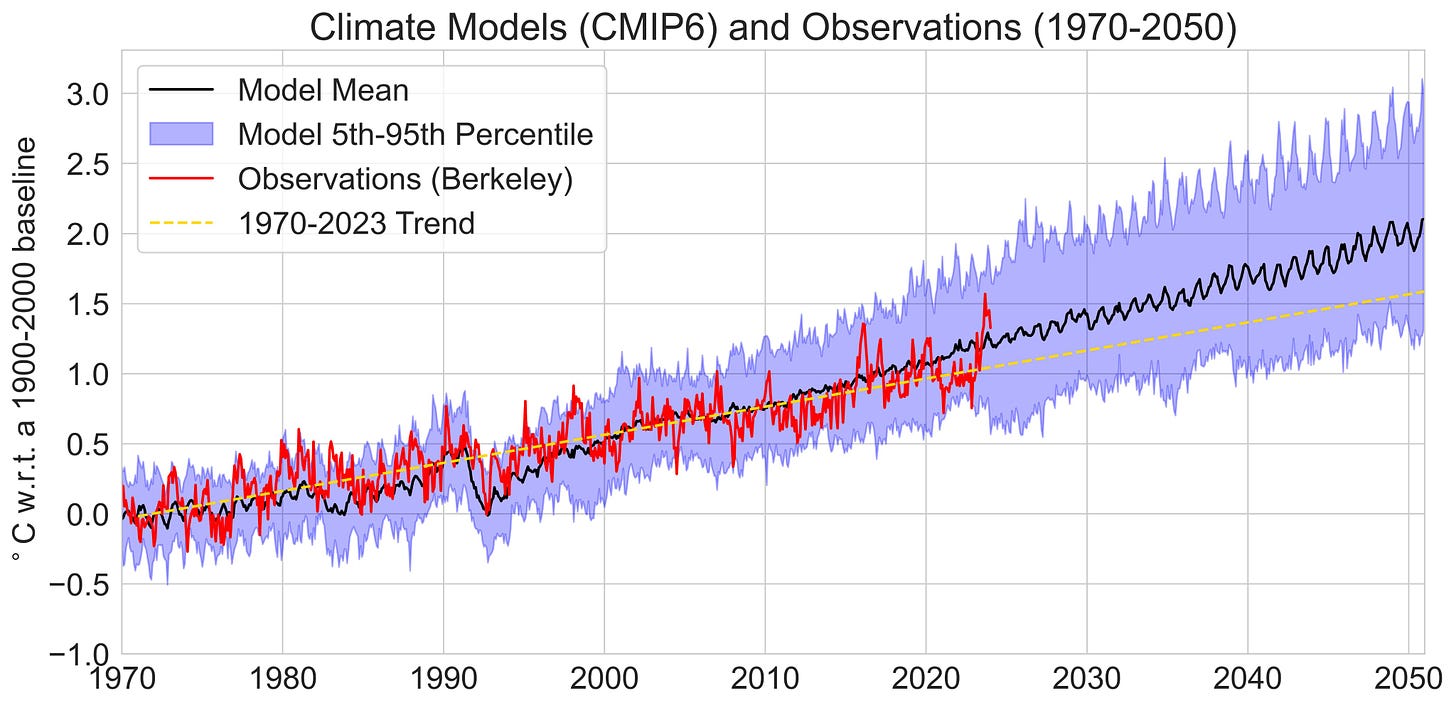

In this post, I compare the observational temperature record to an ensemble of state-of-the-art CMIP6 models to see exactly how unusual 2023 was. It turns out that 2023 is just not that unusual when compared to the model ensemble.

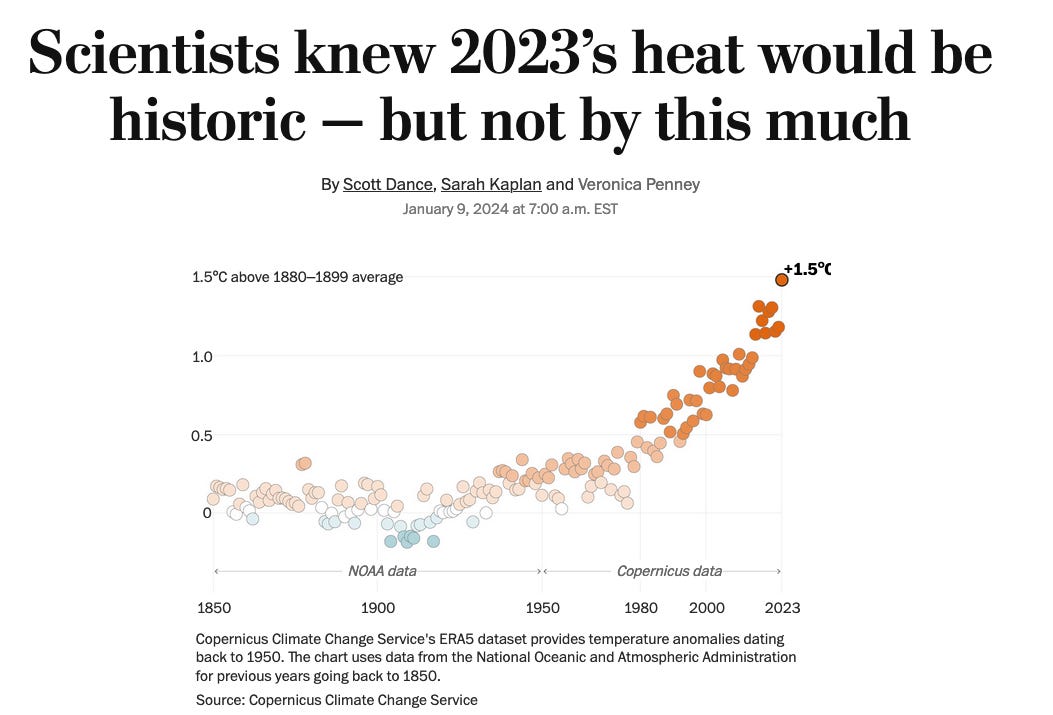

Let’s start with observations. I’m going to be using the Berkeley Earth global average temperature data. In that data set, 2023 was a record-breaking 1.54C above the 1850-1900 average temperature. This temperature exceeded the previous record (set in 2016) by 0.17C.

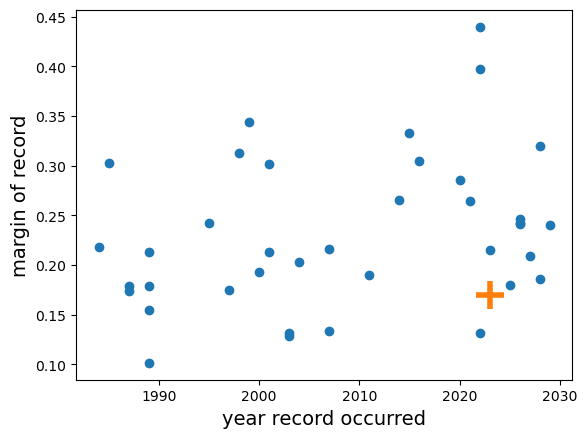

Beating the previous record by 0.17C is huge: if we look at the temperature observations since 1970, the margin by which records were broken averaged 0.07C, with a median of 0.05C. And no record in the last 50 years had a margin larger than 0.17C.

What does the climate model ensemble show? I have analyzed 38 CMIP6 models over the period 1970-2030 driven by historical and SSP4.5 forcing. Here is a plot of the biggest margin for a record year vs. the year that record occurred:

As you can see, the record-breaking margin of 2023, 0.17C, was actually quite modest compared to the climate model ensemble. One model had a year that broke the previous record by nearly 0.45C — all I can say is holy crap, let’s hope that doesn’t happen in the real world.

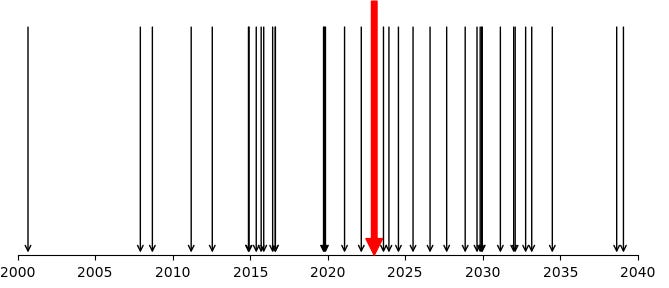

A lot was also made of the fact that 2023 was the first year with a global average temperature anomaly to exceed 1.5C (in some data sets, at least). How unusual is that? Again, we can look at the models to see when they had their first year above 1.5C (as before, relative to the 1850-1900 baseline)1.

The median date for the model ensemble to have its first year above 1.5C is 2024, very close to when we actually did (2023). Thus, the model ensemble seems to be simulating the warming pretty accurately. And the ensemble does equally well for a more modern baseline, like 1970-1990.

Many others have looked at different aspects of the problem and reached similar conclusions. Here’s a plot that Zeke posted on Twitter that shows that the observed temperature time series still falls within the range of models.

This doesn’t mean we know everything about the climate of 2023. The extreme warmth was definitely surprising given the state of the climate in 2022, so important work remains to be done on understanding the physical mechanisms that were driving this record-breaking year.

But the real test of our climate understanding will come in the next few years. If global temperatures drop after the current El Niño fades, as expected, 2023’s high temperatures will be seen as an unusual blip in the long-term evolution of the climate (like “the pause” that occurred in the 2000s). However, if temperatures stay high or, heaven forbid, keep rapidly warming, it would suggest that we’ve broken the climate system. Let’s hope that doesn’t happen.

Arguments

Arguments

Some explanations for the unusual global warming levels in 2023:

James Hansen thinks the anomalously high global surface temperature in 2023 are due to AGW + El Nino + Aerosols reductions. I can't find the related commentary, and have to go by memory, but Hansen suggests that the quite abrupt reductions in shipping aerosols in 2023 added to reductions in industrial aerosols over the last ten years warmed the oceans and this energy comes out after a time delay and it all came out in 2023. Perhaps someone has the details of his suggestion and comments on its credibility.

El ninos release ocean heat that has been building up. I note that the high sea surface temperatures are in the northern oceans are away from the centre of el nino activity.

From NASA: Five Factors to Explain the Record Heat in 2023. But what caused 2023, especially the second half of it, to be so hot? Scientists asked themselves this same question. Here is a breakdown of primary factors that scientists considered to explain the record-breaking heat ( I have cut and pasted the key statements only):

The long-term rise in greenhouse gases is the primary driver.

The return of El Niño added to the heat.

Globally, long-term ocean warming and hotter-than-normal sea surface temperatures played a part.

Aerosols are decreasing, so they are no longer slowing the rise in temperatures.

Scientists found that the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha‘apai volcanic eruption did not substantially add to the record heat.

earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/152313/five-factors-to-explain-the-record-heat-in-2023

From PBS News: ‘We’re frankly astonished.’ Why 2023’s record-breaking heat surprised scientists. A range of factors including general warming due to human-caused climate change, the El Niño climate pattern, record-low Antarctic sea ice and others — contributed to 2023’s record-breaking heat, but they don’t tell the full story. Schmidt said more work has to be done to fully understand why the year was so hot.

“In 2024, we’ll be seeing whether this persists or whether it kind of goes back to a normal pattern,” he said. “And that will be kind of telling as to whether 2023 was just a very unusual combination of things that all added up to what we saw, or whether there’s something systematically different going forward.” (Seems like good comments to me)

www.pbs.org/newshour/science/were-frankly-astonished-why-2023s-record-breaking-heat-surprised-scientists#:~:text=A%20range%20of%20factors%20%E2%80%94%20including,the%20year%20was%20so%20hot.

From Copernicus:

Some alternative suggestions on 2023 warming including changes in regional wind patterns over the northern parts of the oceans bringing heat to the surface:

atmosphere.copernicus.eu/aerosols-are-so2-emissions-reductions-contributing-global-warming

(This is not a reference to el nino, but to other changes in wind patterns to the north. For me it raises the question of caused the changes in wind patterns)

Clearly there is no definitive answer yet on why 2023 was so unusually warm ( ditto 2024 thus far). As scientists say next years data will help illuminate the causes.

What was special about the warming in 2023 was, that it happened all in the last 6 months, so it was a much larger jump over these months then the mean values of 2023.

Further, only a moderate El Nino existed, so not too much warming came from here.

Reasons where:

SOx reductions amplified the marine heatwave signal across the mid-latitudes.

The El Nino in combination with a positive Indian Dipole - both lead to a larger heat release of the tropical oceans as a clear and strong circulation cell is supported over the tropical oceans due to the zonal temperature gradient.

Sea ice reductions around the Antarctic caused circulation changes that led to moist and warm air advection over Antarctica (strong effect on the warming as exceptional heat waves rocked Antarctica), as well as radiative effects of the sea ice reductions and heat release over sea ice-free areas.

Then climate warming warms the oceans now more than natural variability is often able to produce colder than normal SSTs - at one time only some ocean regions existed with colder than normal temperatures.

Then we had the vast expansion of marine heatwaves across the global oceans, especially across the mid-latitudes reaching a coverage of more than 40% in July.

The warmer-than-normal Oceans created a cloud feedback thereby increasing shortwave absorption (reinforces marine heatwaves).

From 2012 to 2016 we had a non-linear increase of moisture in the marine boundary layer caused by exceptional SSTs. The next jump will have happened in 2023 causing a water vapor feedback over large parts of the oceans to increase. And tropical moist air advection is causing marine heatwaves in the subtropics to mid-latitudes. So also here another feedback as more water vapor radiates longwave radiation back to the surface.

Further, we had during summer to autumn large areas where the soil-moisture-temperature cascade came into play producing these exceptional continental heat waves. It comes along with a cloud feedback.

Then we had the pattern effect of increasing temperature gradients in the oceans surface and continents which disturb the overlying circulation, often causing blocking patterns (also a reason for the marine heatwaves to build up)

Then we had towards autumn a heat release of the marine heatwaves across the mid-latitudes, as the atmosphere gets colder.

Last it have been possible that the oceans released heat from the subsurface that had built up. Across the mid-latitudes warm freshening water masses are accumulating under the surface as shallow as 150m depth. And these heat depots could have been tapped, as the jets speed up during winter, as the density gradient between the tropics and poles increases in the upper atmosphere while it decreases near the surface. More and stronger low-pressure systems due to increased shear are the outcome. And all these extreme low-pressure systems in autumn and winter across the mid-latitudes in 2023/24 could have tapped this subsurface heat depot. But now study here as this is new.

Main problem thou is the expansion of marine heatwaves, as they are feedback driven by global warming heating the oceans from the surface too fast (thermal stratification increases non-linear in the upper 300m of the oceans in various regions), in combination with the pattern effect which disturbs global zonal circulation with the result of more stalled high-pressure systems (low wind speeds are in most instances THE precondition for marine heatwaves too form besides thermal stratification and small mixed layer depth).

Last the warming of the northern latitudes can also be included in the factors driving global warming in 2023.

In short the warming of 2023 was feedback-driven by various system forcing each other into a heating mode with the systems of the oceans, atmosphere, and landmasses acting in unison! The exact series of which contributed to what extent to the heating science has to find out. But it would have to do it on a monthly basis!

The next jump will have devastating consequences as they become larger...

Here is my FB page, want now to make my own blog, as the experts lose the oversight and models will be increasingly wrong (the model spread is in my opinion a joke as it is way too large proving the uselessness of models)...

https://www.facebook.com/Erdsystemforschung/

All the best

Jan

p.s. we warm the oceans too fast that is our main problem!

Made it a little bit nicer, as it is important:

On the causes of the exceptional temperature jump in 2023

First things first:

What was special about the warming in 2023 was, that it happened all in the last 6 months, so it was a much larger jump over these months than the mean values of 2023.

Further, only a moderate El Nino existed, so not too much warming came from here.

Reasons where:

SOx reductions over the shipping routes amplified the marine heatwave signal across the mid-latitudes.

The El Nino in combination with a positive Indian Dipole - both lead to a larger heat release of the tropical oceans as a clear and strong circulation cell is supported over the tropical oceans due to the zonal SSTs gradient.

Sea ice reductions around the Antarctic caused circulation changes that led to moist and warm air advection over Antarctica (strong effect on the warming as exceptional heat waves rocked Antarctica), as well as radiative effects of the sea ice reductions and heat release over sea ice-free areas.

Then that climate warming warms the oceans now more than natural variability is often able to produce colder than normal SSTs - at one time only some ocean regions existed with colder than normal temperatures.

Then we had the vast expansion of marine heatwaves across the global oceans, especially across the mid-latitudes reaching a coverage of more than 40% in July.

The warmer-than-normal Oceans created a cloud feedback thereby increasing shortwave absorption (reinforces marine heatwaves).

From 2012 to 2016 we had a non-linear increase of moisture in the marine boundary layer caused by exceptional SSTs. The next jump will have happened in 2023 causing a water vapor feedback over large parts of the oceans to increase. And tropical moist air advection is causing marine heatwaves in the subtropics to mid-latitudes. So also here is another feedback as more water vapor radiates longwave radiation back to the surface.

Further, we had during summer to autumn large areas where the soil-moisture-temperature cascade came into play producing these exceptional continental heat waves. It comes along with a cloud feedback and supports stalled/fixed high-pressure systems as these heat domes redirect the jet around them (higher troposphere).

Then we had the pattern effect of increasing zonal (east/west direction) temperature gradients at the ocean surface and continents which disturb the overlying circulation, often causing blocking patterns (also a reason for the marine heatwaves to build up)

Then we had towards autumn a heat release of the marine heatwaves across the mid-latitudes, as the atmosphere gets colder. Also, cold core and warm cors eddies cause extreme temperature gradients in the western boundary extension regions leading to a larger latent heat releases over these ocean regions (small-scale pattern effect of SSTs increases wind speeds).

Last it has been possible that the oceans released heat from the subsurface that had built up. Across the mid-latitudes warm freshening water masses are accumulating under the surface as shallow as 150m depth. And these heat depots could have been tapped, as the jets speed up during winter, as the density gradient between the tropics and poles increases in the upper atmosphere while it decreases near the surface, especially during winter. More and stronger low-pressure systems due to increased shear are the outcome. And all these extreme low-pressure systems in autumn and winter across the mid-latitudes in 2023/24 could have tapped these subsurface heat depots. But no study here as this is a new development seen in the intensity of the low-pressure systems the last years (e.g. number of atmospheric rivers hitting the US west coast)

Main problem thou is the expansion of marine heatwaves, as they are feedback driven by global warming heating the oceans from the surface too fast (thermal stratification increases non-linear in the upper 300m of the oceans in various regions), in combination with the pattern effect which disturbs global zonal circulation with the result of more stalled high-pressure systems (low wind speeds are in most instances the main precondition for marine heatwaves to form besides thermal stratification and shallow upper mixed layer depth).

Last the warming of the northern latitudes can also be included in the factors driving global warming in 2023.

In short, the warming of 2023 was feedback-driven by various systems forcing each other into a heating mode with the systems of the oceans, atmosphere, and landmasses acting in unison!

The exact series of which contributed to what extent to the heating science has to find out. But it would have to be done on a monthly basis!

The next jump will have devastating consequences as they become larger...

In my opinion, the model spread is now a joke as it is way too large proving the uselessness of models as they will increasingly become unable to predict what is coming as too many parametrizations prevent them from simulating the non-linear character of the mutually reinforcing systems with many processes operating on small scales...

p.s. we warm the oceans too fast from the surface that is our main problem!

Jan @ 2 / 3 :

my computer does not connect to that facebook site

~ possibly the computer figures (genau richtig) that my German abilities are far too small.

"Long story short" ~ are you saying that the recent slightly greater global warmth is a minor temporary excursion or a longer-term feedback that will give many years of greater-than-expected warmth of surface temperatures?

nigelj said: "El ninos release ocean heat that has been building up"

The complement to this is that La Ninas absorb atmospheric heat as the cold thermocline approaches the surface, thus exposing a large area heat sink. Thus, a complete swing is -cold to +hot.

So the fact that we have been in a La Nina state the prior few years makes the warming spike even more stark.

Also the AMO shows a significant El Nino-like peak. This is perhaps expected, as the precursor to this situation occurred in 1878 (see chart below) when one of the largest El Ninos recorded occurred in the Pacific, while a similar scaled peak occurred in the Atlantic's AMO.