NASA-GISS: July 2010-- What global warming looks like

Posted on 13 August 2010 by Doug Bostrom

"Where's the evidence" is the frequent demand of folks doubting what science tells us of climate change. This isn't surprising because we're looking at a system with enormous inertia and so climate shifts will generally show up as incremental creep over a long period of time. We can look at years of results nicely presented by such tools as NOAA's "Climate Indicators" visualization page but what we see there is nothing we'll notice happening on a day by day basis in our lives.

Weather effects of climate change are elusive when it comes to attribution; an unusual spate of hot weather simply can't be put down to a variation in climate without being viewed in a larger context. Indeed it's best for us laypersons to avoid attributing weather we may feel is unusual to any particular cause. Heavy snowfall last winter was frequently cited as evidence of a halt in global warming or evidence that anthropogenic climate change had been exaggerated; our personal feelings overrode what science told us we could expect of climate change.

There is however a means of separating our gut instinct about today's weather from more objective means of assessment. We can look at any day's weather from a statistical viewpoint. Compared to typical climatology, how does today's weather stack up? How does a sequence of days look? What does the frequency and magnitude of new weather records tell us?

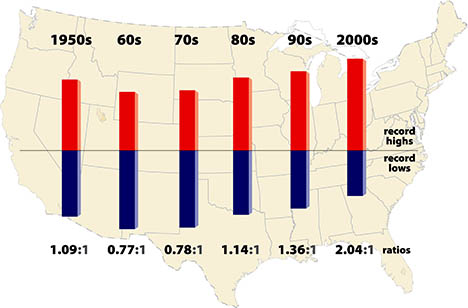

Meehl 2009 looked at weather statistics from the perspective of the ratio of record high and low temperatures over the past few decades. In general we'd expect a large thermometer network of stations in operations for many decades to exhibit a more or less 1:1 relationship of new record highs versus lows. But the statistics clearly show otherwise:

Meehl shows how a statistical look at weather events can tease out information about which way our climate is heading. But this is still not something that can be described as a notable phenomenon, an event that gives us an intuitive feel for the changing behavior of our climate.

Sometimes however unusual weather events and patterns can emerge from the statistical background as a noticeable cluster, a burst of dramatic activity that catches our notice. Our intuition may lead us to wonder if we we're witnessing something more significant than weather.

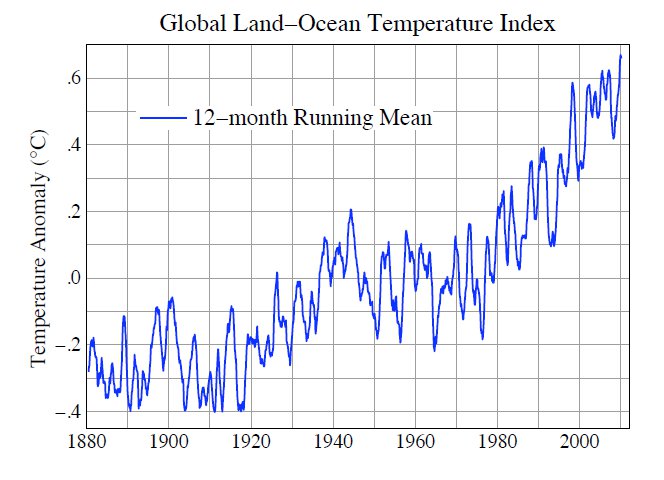

Weather around the planet so far this year has indeed included some unusual events, to put it mildly, occurrences that are notable from a statistical viewpoint and extend a remarkable recent bulge in records. 75 countries or 33% of the nations on Earth have set historical high temperature temperature records in the past 10 years, versus 15 countries setting record lows. 17 countries have set all-time national high temperature records this year, with only a single country reaching a record low. This has happened in a year where global temperature for January through July of this year is the hottest on record. The 12-month running mean of global temperature is at a record high. Unprecedented monsoon flooding in Pakistan has left some 10% of citizens suffering from flood effects with river flows on the Indus exceeding any past measurements. Russia has seen prolonged temperature extremes far outside the historical record, leaving probability in the neighborhood of 1:1000 in terms of how often we'd expect to see such a phenomenon.

These statistics are in fact so startling that NASA-GISS was moved to title their July 2010 Surface Temperature Analysis "July 2010-- What global warming looks like." The report notes the "statistical loading of the dice" produced by climate change:

"The location of extreme events in any particular month depends on specific weather patterns, which are unpredictable except on short time scales. The weather patterns next summer will be different than this year. It could be a cooler than average summer in Moscow in 2011.

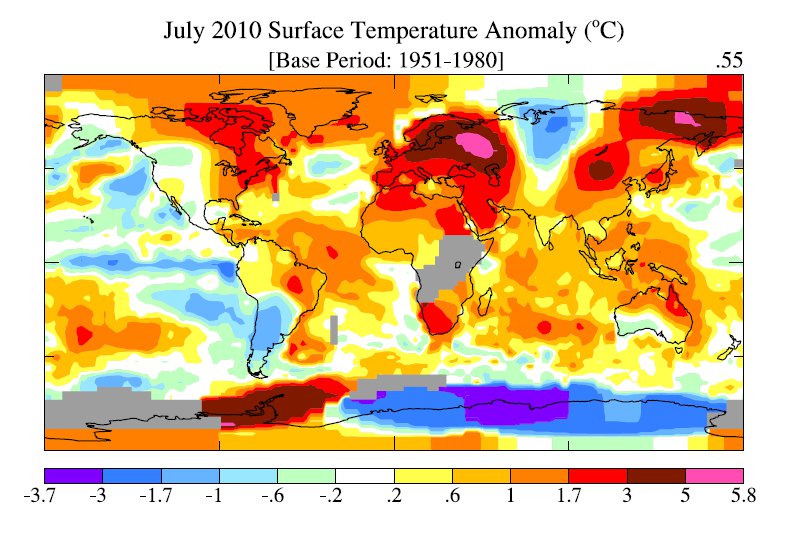

But note in Figure 1, and similar maps for other months, that the area warmer than climatology already (with global warming of 0.55°C relative to 1951-1980) is noticeably larger than the area cooler than climatology. Also the magnitude of warm anomalies now usually exceeds the magnitude of cool anomalies.

What we can say is that global warming has an effect on the probability and intensity of extreme events. This is true for precipitation as well as temperature, because the amount of water vapor that the air carries is a strong function of temperature. So the frequency of extremely heavy rain and floods increases as global warming increases. But at times and places of drought, global warming can increase the extremity of temperature and associated events such as forest fires."

As usual, graphics help us understand the data better. We can see the situation in Russia clearly indicated:

Figure 1 July 2010 NASA-GISS Surface Temperature Anomaly

As we can see from the following graph, the 12 month running mean temperature is at an all time high:

Figure 2 July 2010 NASA-GISS Surface Temperature Analysis

The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) looks at this year more from a weather perspective. In "Current Extreme Weather Sequence" the WMO takes note of the conspicuous nature of this year's weather in Russia:

"According to Roshydromet, the Russian Federal Service for Hydrometeorology and Environmental Monitoring, July 2010 is the warmest month ever in Moscow since the beginning of modern meteorological records, 130 years ago. Temperature has exceeded the long-term average by 7.8° C (compared to the previous record in July 1938 with 5.3° C above average). Record high temperatures varying between 35° C and 38.2° C were registered for more than 7 consecutive days end July, with the heatwave continuing into August. The daily temperature of 38.2° C on 29 July was the highest ever in Moscow (compared to a long-term average of approximately 23° C). The minimum temperature of nearly 25°C (recorded during the night before sunrise) also scored a significant increase compared to the historical average of about 14° C."

The WMO goes on to note events in Pakistan:

"The floods in Pakistan were caused by strong monsoon rains. According to the Pakistan Meteorological Department, the instant rain intensity reached 300 mm over a 36-hour period. The strong monsoon rains led to the highest water levels in 110 years in the Indus River in the northern part of the country, based on past records available from 1929. More areas in central and south Pakistan are affected by the floods. The death toll to date exceeds 1 600 and more than 6 million people have been displaced. Some reports indicate that 40 million citizens have been affected by the floods."

Similarly to NASA-GISS, while careful not to make a bald pronouncement about attribution of these events, neither does WMO avoid pointing out the congruence of unprecedented extreme weather with predictions from climate science:

"Several regions of the world are currently coping with severe weather-related events: flash floods and widespread flooding in large parts of Asia and parts of Central Europe while other regions are also affected: by heatwave and drought in Russian Federation, mudslides in China and severe droughts in sub-Saharan Africa. While a longer time range is required to establish whether an individual event is attributable to climate change, the sequence of current events matches IPCC projections of more frequent and more intense extreme weather events due to global warming. The Monsoon activity in Pakistan and other countries in South-East Asia is aggravated by the la Niña phenomenon, now well established in the Pacific Ocean"

The WMO has more to say on this in their update. It's conspicuous and of course admirable that neither NASA-GISS nor WMO attempt to say "Here's your proof of global warming." Equally it's important that both organizations continue to use their analytic resources to mark those occasions when observations coincide with predictions. 2010 has so far provided ample opportunities for such connections to be pointed out.

All of us live just a single human lifespan; nobody reading these words is likely to wake up 100 years from now and wax nostalgic for the way the weather used to be. As NASA-GISS' title implies, for those of us living in 2010 clusters of statistically extreme weather events are the best grip any of us as individuals will get on what global warming looks like.

Arguments

Arguments

0

0  0

0 This picture, taken from www.climate4you.com shows quite other things than you claim. The use of a 12-month running average is a convenient trick to show an intermediate all time high, when you expect that the annual average of the running year will not break records. Such an average has no climatological meaning for the long term trends.

Dough-Bostrom (#29). Yes, you are right, Nasa used these words first. John, I apologize. But this makes things even worse. I should have written: 'Nasa has not learnt from the attribution errors that the IPCC made in 2005'.

This picture, taken from www.climate4you.com shows quite other things than you claim. The use of a 12-month running average is a convenient trick to show an intermediate all time high, when you expect that the annual average of the running year will not break records. Such an average has no climatological meaning for the long term trends.

Dough-Bostrom (#29). Yes, you are right, Nasa used these words first. John, I apologize. But this makes things even worse. I should have written: 'Nasa has not learnt from the attribution errors that the IPCC made in 2005'.

And this is the anomaly for last winter:

And this is the anomaly for last winter:

I find it interesting to notice that the anomalies have a similar pattern in both pictures. Is it then to much to ask if there exists a causal relation between these two pictures/pattern? And if it happens to be so why are they then attributed to different causes?

Anyway, then you continue with comparing climate science with seismologists and earthquakes, and at this point I am completely lost in what your comment wants to clarify to me.

Finally you end your first post at me with a comment that suggest that I would deny "scientific consensus". Whatever you mean with this would you like to point at what I wrote that made you think so?

In your second comment you mention that you think La Nina is a distraction from "the big picture", but if that was the reason, why didnt you say so in the first place then?

I find it interesting to notice that the anomalies have a similar pattern in both pictures. Is it then to much to ask if there exists a causal relation between these two pictures/pattern? And if it happens to be so why are they then attributed to different causes?

Anyway, then you continue with comparing climate science with seismologists and earthquakes, and at this point I am completely lost in what your comment wants to clarify to me.

Finally you end your first post at me with a comment that suggest that I would deny "scientific consensus". Whatever you mean with this would you like to point at what I wrote that made you think so?

In your second comment you mention that you think La Nina is a distraction from "the big picture", but if that was the reason, why didnt you say so in the first place then?

Comments