The economic impacts of carbon pricing

What the science says...

| Select a level... |

Basic

Basic

|

Intermediate

Intermediate

|

Advanced

Advanced

| ||||

|

The costs of inaction far outweigh the costs of mitigation. |

|||||||

CO2 limits will harm the economy

"Legally mandated measures for reducing greenhouse gas emissions are likely to have significant adverse impacts on GDP growth of developing countries [...] This in turn will have serious implications for our poverty alleviation programs." (Pradipto Ghosh)

If climate change proceeds without any efforts to reduce it, we can expect to incur serious economic costs. In fact, it's not unreasonable to expect that the effects of climate change will create greater economic instability worldwide.The solution is, of course, to reduce fossil fuel use. One way to do this is to shift away from fossil fuels towards renewable energy sources. The other way is to reduce energy demands through increased efficiency.

Both mechanisms have economic implications. In order to stimulate the private sector’s investment in renewables, governments can put a levy on fuels, which may be used to fund or subsidise new initiatives.

To reduce demand, there are a number of solutions available, but most seek to raise the cost of carbon through taxes. Such increased costs give rise to concerns that change underwritten by taxes or levies will damage economic prospects, particularly in developing countries. However, there is a consensus among economists with expertise in climate that we should put a price on carbon emissions.

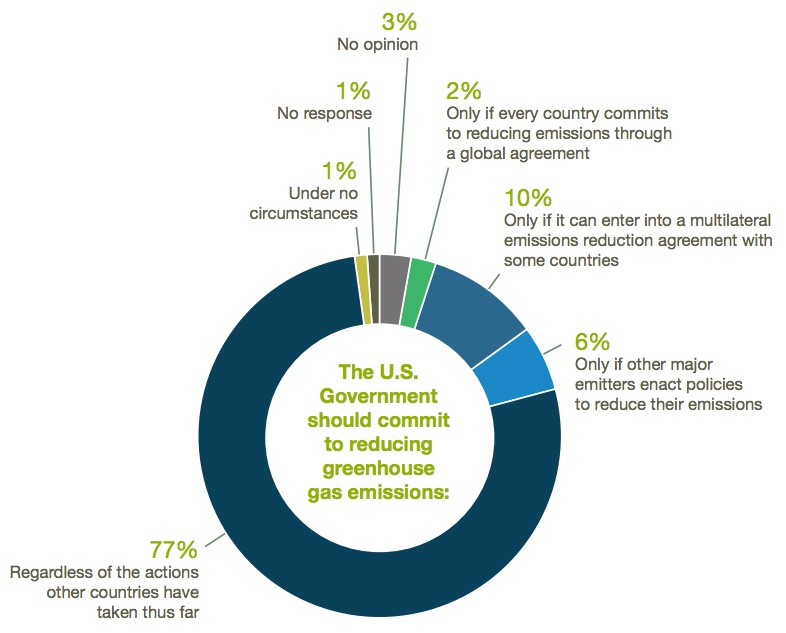

2015 New York University survey results of economists with climate expertise when asked under what circumstances the USA should reduce its emissions

The Representative Picture

In the Fifth IPCC Assessment Report (AR5), a new set of scenarios called Representative Concentration Pathways (RCP) will be used. The four RCPs replace the previous scenarios from the "Special Report on Emissions Scenarios" (SRES). Each RCP represents a set of initial conditions and projections to year 2100, based on a synthesis of the peer-reviewed literature.

The graphs below show the predicted RCP trajectories for economic performance:

GDP projections of the four scenarios underlying the RCPs (van Vuuren et.al. 2011). Grey area for income indicates the 98th and 90th percentiles (light/dark grey) of the IPCC AR4 database (Hanaoka et al. 2006). The dotted lines indicate four of the SRES marker scenarios.

The number of each RCP is the forcing (in watts per square metre) associated with a specific amount of emissions for each scenario, up to the year 2100. The graph of GDP clearly shows that the pathways that reduce emissions the most in that time frame (2.6 - green, and 4.5 - red) are those with the best long-term economic performance. In other words, the investment required to reduce emissions is repaid by increased economic performance. Business as usual strategies (high-emission scenarios RCP 6 and 8.5) are the least profitable; the money saved early on is dwarfed by the costs of damage and disruption done in the longer term.

Putting a Price on Carbon

There are a number of schemes under consideration, and a number already implemented. According to the article Pollution Economics in the New York Times, more than 20 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions are now subject to carbon pricing systems. About 60 other states, provinces or countries are considering similar approaches, according to a recent World Bank report.

It’s too early to judge long-term economic performance of the early adopters, but Canada’s province of British Columbia serves as a good example of how carbon pricing can reduce fuel use - in their case through a revenue-neutral scheme. A recent study found that since 1st July 2008, when the tax was introduced:

- BC’s fuel consumption has fallen by 17.4% per capita (and fallen by 18.8% relative to the rest of Canada).

- These reductions have occurred across all the fuel types covered by the tax (not just vehicle fuel)

- BC’s GDP kept pace with the rest of Canada’s over that time

- The tax shift has enabled BC to have Canada’s lowest income tax rates (as of 2012).

- The tax shift has benefited taxpayers; cuts to income and other taxes have exceeded carbon tax revenues by $500 million from 2008-12.

Source: BC’s Carbon Tax Shift After Five Years: Results, Elgie & McClay 2013

In a separate report, the British Columbia Department of Finance found that in 2012, BC's taxes were among the lowest corporate tax rates in North America and the G7 nations.

Conclusions

There is a consensus among expert climate economists that carbon pollution limits are needed to prevent climate change from badly damaging the global economy.

A number of economic incentives are being tried with varying degrees of success. Regional schemes are already proving effective, flexible and popular. An important ingredient seems to be an accompanying tax reduction that makes the carbon tax revenue-neutral.

In the long term, unless we drastically reduce the rate at which we are still emitting greenhouse gases, we are very likely to incur huge costs as a result of climate change. Part of these costs will be in adaptation, and the inevitable disruption. In part costs will escalate due to turmoil and uncertainty throughout the economic world. There will also be costs that cannot be quantified, particularly when we try to value a human life and its loss.

We have to reduce our emissions. If we are to avoid draconian government intervention, carbon pricing schemes are a viable method of encouraging us to reduce fossil fuel use. Coupled with other measures to stimulate renewable energy development, putting a price on carbon may help us make the transition away from fossil fuels. And from our experience to date, it seems likely that carbon taxes, instead of bringing an economy to its knees, may well help transform an outdated system into one fitting for a sustainable century.

Basic Rebuttal written by GPWayne and dana1981

Last updated on 2 January 2016 by dana1981. View Archives

Arguments

Arguments

Climate Myth...