Global warming made Hurricane Harvey more destructive

Posted on 23 May 2018 by John Abraham

Last summer, the United states was pummeled with three severe hurricanes in rapid succession. It was a truly awesome display of the power of weather and the country is still reeling from the effects. In the climate community, there has been years of research into the effect that human-caused global warming has on these storms – both their frequency and their power.

The prevailing view is that in a warming world, there will likely be fewer such storms, but the storms that form will be more severe. Some research, however, concludes that there will be both more storms and more severe ones. More generally, because there is more heat, there is more activity, which can be manifested in several ways.

Regardless, there is very little doubt that a warmer planet can create more powerful storms. The reason is that hurricanes feed off of warmer ocean water. In order to form these storms, oceans have to be above about 26°C (about 80°F). With waters that hot, and with strong winds, there is a rapid evaporation of moisture from the ocean. The resulting water vapor enters into the storm, providing the energy to power the storm as the water vapor condenses and falls out of the storm as rain.

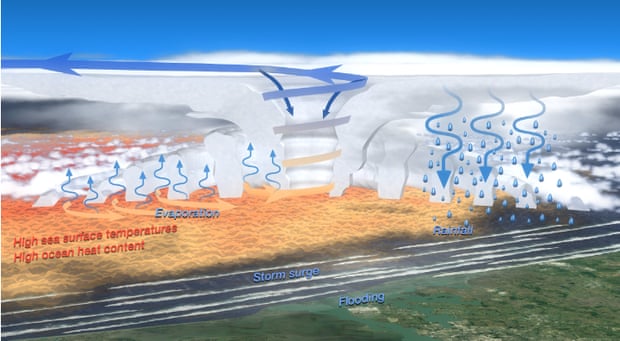

As a large hurricane passes over warm water, it sucks in heat not only from the top layer of water but also from quite deep in the ocean, at least 160 meters (approximately 525 feet) or more. The main way heat is pulled out of the ocean is through the aforementioned evaporation process. There are also smaller effects from mixing the ocean waters and blocking sunlight to the ocean. Basically, when a hurricane passes over warm waters, the ocean “sweats” and cools off – a process enabled by the strong winds. The image below shows this evaporation and condensation process.

Diagram of evaporation and rainfall within a hurricane. Illustration: Trenberth et al. (2018), Earth's Future

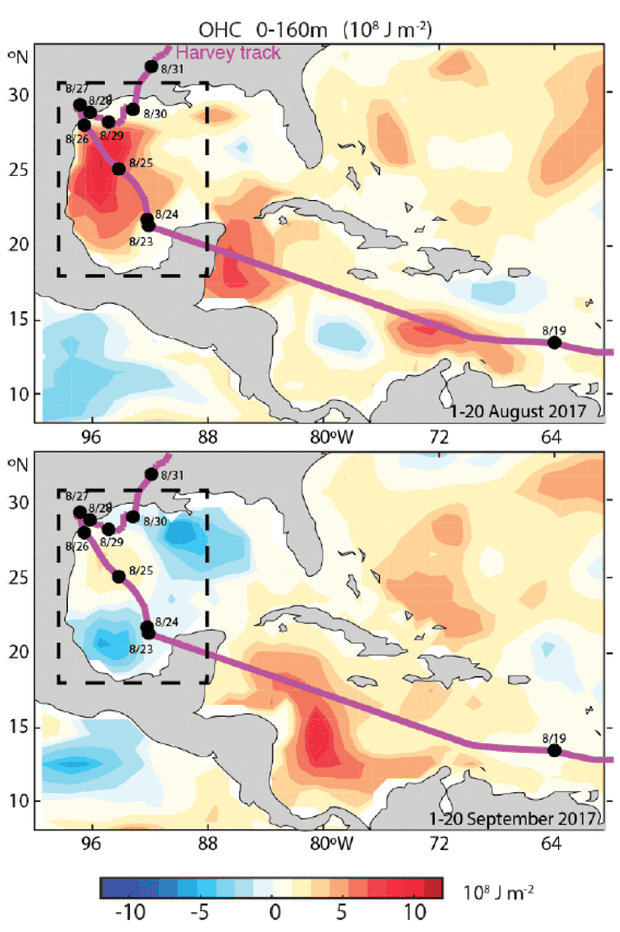

A very recent publication in the journal Earth’s Future studied the impact of hurricanes on warm oceans in order to understand how warm waters fuel the storms and also how storms affect the water temperatures. With Hurricane Harvey, a near perfect natural laboratory was available in the Gulf of Mexico. Temperature measurements are plentiful there and the scientists were able to measure the total ocean heat content in the upper 160 meters just before Hurricane Harvey passed and compare the heat measured after the storm.

What they found was very interesting. As seen in the image below, before the storm (top frame), the ocean heat content was very high (red colors). After the hurricane passed (bottom frame), the waters were notably cooler.

Cooling off of ocean waters because of Hurricane Harvey. Illustration: Trenberth et al. (2018), Earth's Future

The scientists calculated that the waters lost approximately 6 x 1020 Joules of heat because of Harvey. That’s about 10 million times as much energy as the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima. Then the scientists used rainfall data and calculated how much heat fell in the form of rain. The results were a nearly perfect match with the energy taken up by the storm. That is, they were able to balance the energy and water flows into and out of the storm to a very high level of accuracy.

Arguments

Arguments

Hurricane Harvey's forward progress stalled as it made landfall in Texas and it meandered along the coast toward Houston. Thus its rainfall was concentrated in a relatively small area for an extended period and thus caused more severe flooding.

One or more areas of high pressure caused Hurricane Harvey to stall then track the way it did along the Texas coast. High pressure areas are not a recent occurrence caused by global warming.

Recommended supplemental reading:

Stronger, Wetter, Slower: How Hurricanes Will Change by Mark Fischetti, Scientific American, May 30, 2018

Does global warming make tropical cyclones stronger? by Stefan Rahmstorf, Kerry Emanuel, Mike Mann & Jim Kossin, Real Climate, May 30, 2018

Areas of high and low air pressure will continue to be the major determinant of hurricane direction and speed.