Climate solutions come in all shapes and sizes, and at Yale Climate Connections, we started off the year with the launch of our climate solutions hub, a page designed to help you easily identify climate actions that fit into your life. It’s a great place to find a climate-related New Year’s resolution if that’s your jam.

To close 2025 out on a high note, check out our favorite solutions stories of the year.

Sara Peach, editor-in-chief:

The solar panels Germans are plugging into their walls, by Yale Climate Connections’ radio team

In Germany, people who want to go solar can simply go to the store, buy a solar panel, and plug it in at home. These plug-in solar systems send power directly into a home through a normal wall outlet.

(Sara says, “This development makes solar panels accessible to renters. When it’s time to move, just unplug the panel and carry it to your new apartment.”)

Bill McKibben says cheap solar could topple Big Oil’s power, by Michael Svoboda

There is one big good thing happening on this planet. And that is the sudden surge in the use of what, for the last 40 years, we’ve called alternative energy, but which has now become the most obvious, straightforward way to make power.

Pearl Marvell, features editor, Yale Climate Connections en español:

He wasn’t planning to step in – until his team informed him that some immigrant enclaves were still waiting on help a month after the storm. They brainstormed a list of what families must need as winter approached: coats, heaters, blankets, generators, food, cash. When they began distributing items, many told the group that theirs was the first to offer them help.

(Pearl says, “I love this article because Yessenia wrote this story so beautifully and focused it primarily on how this community came together to help each other in times of need. I love when we can tell stories that are people-focused and then backed up by science.)

The rest of the world is lapping the U.S. in the EV race, by Dana Nuccitelli

According to an analysis by the International Council on Clean Transportation, climate pollution from global road transportation may have peaked in 2025 thanks to accelerating EV deployments around the world.

(Pearl says, “Because at least the rest of the world is going in the right direction.”)

How to steer EVs towards the road of ‘mass adoption’

Posted on 5 January 2026 by Guest Author

This is a re-post from Carbon Brief by Izzy Woolgar, director of external affairs at the Centre for Net Zero; Andy Hackett, senior policy adviser at the Centre for Net Zero; and Laurens Speelman, principal at the Rocky Mountain Institute

Electric vehicles (EVs) now account for more than one-in-four car sales around the world, but the next phase is likely to depend on government action – not just technological change.

That is the conclusion of a new report from the Centre for Net Zero, the Rocky Mountain Institute and the University of Oxford’s Environmental Change Institute.

Our report shows that falling battery costs, expanding supply chains and targeted policy will continue to play important roles in shifting EVs into the mass market.

However, these are incremental changes and EV adoption could stall without efforts to ensure they are affordable to buy, to boost charging infrastructure and to integrate them into power grids.

Moreover, emerging tax and regulatory changes could actively discourage the shift to EVs, despite their benefits for carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, air quality and running costs.

This article sets out the key findings of the new report, including a proposed policy framework that could keep the EV transition on track.

A global tipping point

Technology transformations are rarely linear, as small changes in cost, infrastructure or policy can lead to outsized progress – or equally large reversals.

The adoption of new technologies tends to follow a similar pathway, often described by an “S-curve”. This is divided into distinct phases, from early uptake, with rapid growth from very low levels, through to mass adoption and, ultimately, market saturation.

However, technologies that depend on infrastructure display powerful “path-dependency”, meaning decisions and processes made early within the rollout can lock in rapid growth, but equally, stagnation can also become entrenched, too.

EVs are now moving beyond the early-adopter phase and beginning to enter mass diffusion. There are nearly 60m on the road today, according to the International Energy Agency, up from just 1.2m a decade ago.

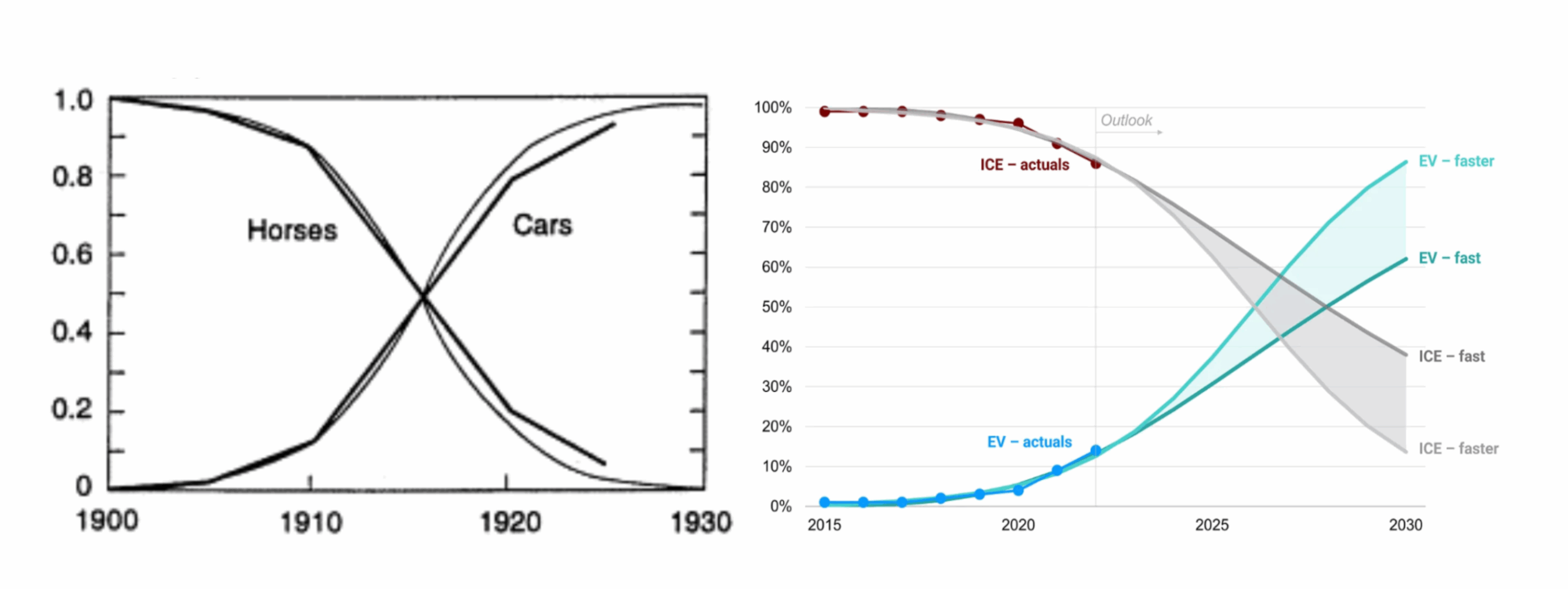

Technological shifts of this scale can unfold faster than expected. Early in the last century in the US, for example, millions of horses and mules virtually disappeared from roads in under three decades, as shown in the chart below left.

Yet the pace of these shifts is not fixed and depends on the underlying technology, economics, societal norms and the extent of government support for change. Faster or slower pathways for EV adoption are illustrated in the chart below right.

Left: The S-curve from horses to cars. Right: The predicted shift from ICE to EVs. Note that S-curves present technology market shares from fixed saturation levels to show the shape of diffusion, rather than absolute numbers; Cars were both a substitute for, and additional to, horses. Sources: Grubler (1999), Technology and Global Change (left); Rocky Mountain Institute, IEA data (2023) (right).

Left: The S-curve from horses to cars. Right: The predicted shift from ICE to EVs. Note that S-curves present technology market shares from fixed saturation levels to show the shape of diffusion, rather than absolute numbers; Cars were both a substitute for, and additional to, horses. Sources: Grubler (1999), Technology and Global Change (left); Rocky Mountain Institute, IEA data (2023) (right).

2026 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming News Roundup #01

Posted on 4 January 2026 by BaerbelW, Doug Bostrom

Year 2025 Statistics

As this is the first news roundup of 2026 and we therefore have the complete year 2025 "in the can", we thought that you might enjoy some stats about what we shared during the previous 12 months.

All told, we shared 1470 links from about 270 different outlets, the vast majority of which provided fewer than 10 links and the bulk of shares originated from just 25 different outlets. The Top10 are: The Guardian (190), Skeptical Science (164), Inside Climate News (108), Yale Climate Connections (67), Phys.org (63), Carbon Brief (58), New York Times (54), The Conversation (52), Grist (47), CNN (38), followed by The Climate Brink, The Washington Post, DeSmog, Climate Home News and NPR. Among the shares are also 53 links to Youtube videos from different creators like ClimateAdam, "Just have a think", Dr Gilbz or Potholer54.

When looking at the categories we put most of the shared articles into Climate Change Impacts followed by - not too surprisingly! - Climate Policy and Politics and Climate Science and Research. Here is the full list for the 1470 articles shared:

| Category | Articles |

| Climate Change Impacts | 379 |

| Climate Policy and Politics | 324 |

| Climate Science and Research | 148 |

| Public Misunderstandings about Climate Science | 118 |

| Miscellaneous (Other) | 114 |

| Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation | 93 |

| Climate education and communication | 92 |

| International Climate Conferences and Agreements | 69 |

| Public Misunderstandings about Climate Solutions | 47 |

| Climate law and justice | 45 |

| Health aspects of climate change | 37 |

| Geoengineering | 4 |

Stories we promoted this week, by category:

Climate Change Impacts (9 articles)

- Australia makes list of 2025`s costliest climate events Sydney Morning Herald, Poppy Johnston, Dec 28, 2025.

- Heat, drought and fire: how extreme weather pushed nature to its limits in 2025 National Trust says these are ‘alarm signals we cannot ignore’ as climate breakdown puts pressure on wildlife The Guardian, Steven Morris, Dec 29, 2025.

- 2025 was one of three hottest years on record, scientists say Phys.org, Alexa St. John, Dec 30, 2025.

- Climate change could cost businesses big time The total climate-related financial risks top $6 trillion at 4,000 of the world’s large companies. Yale Climate Connections, YCC Team, Dec 30, 2025.

- An Idaho Bird Research Station Rises From the Ashes of a Wildfire The Valley Fire torched Lucky Peak in the fall of 2024. Bird researchers there are channeling their grief into study of how avians respond to climate-driven blazes. Inside Climate News, William von Herff, Dec 31, 2025.

- Now in its 25th Year, a Historic Effort to Save the Everglades Evolves as the Climate Warms Everglades restoration was designed to replenish the drinking water supply in one of the fast-growing parts of the nation. The same effort may help save South Florida from climate change. Inside Climate News, Amy Green, Jan 01, 2026.

- Hundreds of ski slopes lie abandoned... will nature reclaim the Alps? Dead ski resorts are undeniable evidence of our warming the planet, and another mess to clean up. Irish Examiner, Staff, Jan 01, 2026.

- A once-sparkling Alaskan river has turned a sickly orange color As permafrost melts, metals stored in rocks leach into the water, making it toxic for fish. Yale Climate Connections, YCC Team, Jan 01, 2026.

- Winter blooming of hundreds of plants in UK `visible signal` of climate breakdown New year plant hunt shows rising temperatures are shifting natural cycles of wildflowers such as daisies. World news The Guardian, Ajit Niranjan, Jan 02, 2026.

Skeptical Science New Research for Week #1 2026

Posted on 1 January 2026 by Doug Bostrom, Marc Kodack

Open access notables

Editorial: Surviving the Anthropocene: the 3 E’s under pressing planetary issues, Sanita Lima et al., Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution

Scientists, including stratigraphists, all agree that our species has changed planet Earth in unprecedented ways. But contention exists around the actual start date and the diachronicity of the global human impact (Boivin et al., 2024). Indeed, the term “Anthropocene” is not the first attempt to name the consequences of human activities on our planet (Steffen et al., 2011), and several starting dates for the Anthropocene (from the emergence of the human species to the Great Acceleration and nuclear tests) have been eloquently defended (Logan, 2022). Furthermore, given the social and monetary aspects of the Anthropocene, terms like Capitalocene have been proposed as well (Moore, 2016). As highlighted in this Research Topic, López-Corona and Magallanes-Guijón introduce the concept of Technocene and explain why human technology must take a central place in the definition of our current period. Interestingly, the existence of so many terms trying to explain our impact on Earth could already be an indicator that we are, in fact, in a moment at which human interference is changing Earth’s natural history.

Relationships between climate change perceptions and climate adaptation actions: policy support, information seeking, and behaviour, van Valkengoed et al., Climatic Change

People are increasingly exposed to climate-related hazards, including floods, droughts, and vector-borne diseases. A broad repertoire of adaptation actions is needed to adapt to these various hazards. It is therefore important to identify general psychological antecedents that motivate people to engage in many different adaptation actions, in response to different hazards, and in different contexts. We examined if people’s climate change perceptions act as such general antecedents. Questionnaire studies in the Netherlands (n = 3,546) and the UK (n = 803) revealed that the more people perceive climate change as real, human-caused, and having negative consequences, the more likely they are to support adaptation policy and to seek information about local climate impacts and ways to adapt. These relationships were stronger and more consistent when the information and policies were introduced as measures to adapt to risks of climate change specifically. However, the three types of climate change perceptions were inconsistently associated with intentions to implement adaptation behaviours (e.g. installing a green roof). This suggests that climate change perceptions can be an important gateway for adaptation actions, especially policy support and information seeking, but that it may be necessary to address additional barriers in order to fully harness the potential of climate change perceptions to promote widespread adaptation behaviour.

From this week's government/NGO section:

Unequal evidence and impacts, limits to adaptation: Extreme Weather in 2025, Otto et al., World Weather Attribution

Every December we are asked the same question: was it a bad year for extreme weather? And each year, the answer becomes more unequivocal: yes. Fossil fuel emissions continue to rise, driving global temperatures upward and fueling increasingly destructive climate extremes across every continent. Although 2025 was slightly cooler than 2024 globally, it was some of the worst extreme weather events of 2025 that were studied, documenting the severe consequences of a warming climate and revealing, once again, how unprepared people remain. Across the 22 extreme events that are analyzed in depth, heatwaves, floods, storms, droughts and wildfires claimed lives, destroyed communities, and wiped-out crops. Together, these events paint a stark picture of the escalating risks we face in a warming world

Counting the Cost 2025. A year of climate breakdown, Joe Ware and Oliver Pearce, Christian Aid

The authors identify the 10 most expensive and impactful climate disasters of 2025. The year 2025 was marked by a series of devastating climate events, from heatwaves that pushed the limits of human survival, to record-breaking hurricanes that overwhelmed disaster response systems, and catastrophic rainfall and droughts that wreaked havoc on vulnerable communities. The report underscores the escalating cost of climate change, with fossil fuel companies playing a central role in driving the crisis. The cost of climate inaction is equally clear, as communities continue to bear the brunt of a crisis that could have been averted with urgent action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

2025 Climate Survey, The National Institute for Climate and Environmental Policy at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev

Levels of concern about the impacts of climate change are high across the public, but readiness to change lifestyles is low, especially when it involves personal sacrifice. The data indicate that religious affiliation explains climate attitudes in Israel more strongly than political affiliation.

44 articles in 22 journals by 242 contributing authors

Physical science of climate change, effects

Mechanisms of Projected Changes in Thunderstorm Downburst Environments Across the United States, Williams & Fieweger, 10.22541/essoar.175214727.71008323/v1

Observed and Modeled Trends in Downward Surface Shortwave Radiation Over Land: Drivers and Discrepancies, McKinnon & Simpson Simpson, Geophysical Research Letters Open Access 10.1029/2025gl119493

2025 in review - busy in the boiler room

Posted on 31 December 2025 by BaerbelW, Doug Bostrom

Quite a lot has been happening during 2025 but a good chunk of it is hidden away in our "boiler room" as we were working on a complete revamp of our homepage (see the sneak peek section below).

As in previous recaps, this one is divided into several sections:

|

Direct Air Capture

Posted on 30 December 2025 by Ken Rice

This is a re-post from And Then There's Physics

I thought I’d written about this before, but can’t seem to find a post. Either, my searching ability is poor, or my memory is poor. I mostly wanted to highlight an interesting YouTube video by David Kipping that illustrates why Direct Air Capture (DAC) is thermodynamically challenging. I encourage you to watch the video (which I’ve put at the end of this post) but his basic conclusion is that thermodynamic constraints mean that implementing DAC at the necessary scale would require a significant fraction of all global electricity consumption.

I wanted, however, to work through some of the numbers myself and to do the calculation of how much DAC we would need to use in a slightly different way.

A key point is that given an atmospheric concentration of 400 ppm and a temperature of 300K, it takes a minimum of 19505 J to remove 1 mole of CO2. 1 mole of CO2 is 44g, so 1 tonne of CO2 has 22727 moles. Therefore, removing 1 tonne of CO2 requires a minimum of 4.43 x 108 J.

Typically, however, we emit so much that we tend to think in terms of gigatonnes of CO2 (GtCO2). Removing 1 GtCO2 would require a minimum of 4.43 x 1017 J.

IEA: Declining coal demand in China set to outweigh Trump’s pro-coal policies

Posted on 29 December 2025 by Guest Author

This is a re-post from Carbon Brief by Josh Gabbatiss

China’s coal demand is set to drop by 2027, more than cancelling out the effects of the Trump administration’s coal-friendly policies in the US, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA).

Global coal demand is due to grow by 0.5% year-on-year to reach record levels in 2025, according to the latest figures in the IEA’s annual market report.

Yet this will be reversed over the next couple of years, as a faster-than-expected expansion of renewables in key Asian nations and “structural declines” in Europe push coal demand down, the agency says.

While US coal demand is set to continue falling, the decline will be slower than expected last year, due to new federal government efforts to support the fuel.

However, the IEA’s upward revision of an extra 38m tonnes (Mt) of US coal use in 2027 is dwarfed by an even larger 126Mt downward revision in China’s coal use.

‘Unusual trends’

Coal demand will reach 8,845Mt around the world in 2025. This is slightly (44Mt) higher than the IEA had forecast in its 2024 coal market report.

The agency notes some “unusual regional trends” impacting this growth, including a 37Mt year-on-year increase in US coal demand in 2025 to 516Mt. This is 59Mt (17%) higher than the IEA projected in 2024.

A new suite of measures under the Trump administration have supported the short-term use of coal, including the modernisation of existing coal plants and reopening shuttered ones.

EU coal use declined at a slower pace than expected due to lower wind and hydropower output, according to the IEA. Nevertheless, the bloc “continues its structural decline” in coal demand, driven by renewables expansion, carbon pricing and coal phaseout pledges.

India saw an unexpected dip in coal consumption in 2025, linked to a strong monsoon season that increased hydropower output and curbed electricity demand.

In China, which accounts for more than half of the world’s coal use, coal demand remained roughly unchanged between 2024 and 2025, the IEA says.

2025 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming News Roundup #52

Posted on 28 December 2025 by BaerbelW, Doug Bostrom

Stories we promoted this week, by category:

Climate Policy and Politics (8 articles)

- Lost Science - She Tracked the Health of Fish That Coastal Communities Depend On Ana Vaz monitored crucial fish stocks in the Southeast and the Gulf of Mexico until she lost her job at NOAA. New York Times, Interview by Austyn Gaffney, Dec 18, 2025.

- Save NCAR Field notes from New Orleans, where I and 20,000 colleagues learned that Trump intends to destroy the National Center for Atmospheric Research. Deep Convection, Adam Sobel, Dec 21, 2025.

- “Destroying Knowledge”: Michael Mann on Trump’s Dismantling of Key Climate Center in Colorado Democracy Now, Amy Goodman, Dec 22, 2025.

- Trump`s shuttering of the National Center for Atmospheric Research is Stalinist | Michael Mann and Bob Ward This is the latest in the relentless purge of climate researchers who refuse to be co-opted by the fossil fuel industry The Guardian, Michael Mann and Bob Ward, Dec 22, 2025.

- Looking Back at a Historic Year of Dismantling Climate Policies The Trump administration has aggressively pulled America away from its global role in climate and environmental research, diplomacy, regulation and investment. New York Times, David Gelles, Dec 23, 2025.

- We analyzed 73,000 articles and found the UK media is divorcing 'climate change' from net zero The Conversation, James Painter, Dec 24, 2025.

- Trump`s anti-climate policies are driving up insurance costs for homeowners, say experts Tariffs, extreme weather events and the president’s funding cuts are contributing to increasing rates, sometimes by double digits. Yale Climate Connections, Marcus Baram, Capital & Main, Dec 24, 2025.

- White House pushes to dismantle leading climate and weather research center PBS News Hour, William Brangham, Dec 26, 2025.

Climate Change Impacts (7 articles)

- Arctic Warming Is Turning Alaska’s Rivers Red With Toxic Runoff A yearly checkup on the region documents a warmer, rainier Arctic and 200 Alaskan rivers “rusting” as melting tundra leaches minerals from the soil into waterways. New York Times, Eric Niiler, Dec 16, 2025.

- Washington State Faces Climate Change Reality After Storms Two weeks of “atmospheric river” deluges took a toll on business in Leavenworth, Wash., and beyond, reminding the region that a warming planet has brought new uncertainty. New York Times, Anna Griffin and Amy Graff, Dec 22, 2025.

- Report: Climate is central to truth and reconciliation for the Sámi in Finland As Finland reckons with its historic mistreatment of the Indigenous Sámi people, climate change complicates the path forward. Grist, Rebecca Egan McCarthy, Dec 23, 2025.

- Oceans are supercharging hurricanes past Category 5 Warming oceans are fueling a surge of extreme, off-the-charts storms—so powerful that scientists say it’s time to invent a whole new hurricane category. Science Direct, AGU, Dec 25, 2025.

- The Guardian view on adapting to the climate crisis: it demands political honesty about extreme weather | Editorial Over the holiday period, the Guardian leader column is looking ahead at the themes of 2026. Today we look at how the struggle to adapt to a dangerously warming world has become a test of global justice The Guardian, Editorial, Dec 26, 2025.

- Six photos show how climate change shaped our world in 2025 This year’s most notable wildfires, hurricanes, droughts, heat waves, and heavy rains were made more devastating and deadly by climate change. Yale Climate Connections, Samantha Harrington, Dec 26, 2025.

- Cyclones, floods and wildfires among 2025`s costliest climate-related disasters Christian Aid annual report’s top 10 disasters amounted to more than $120bn in insured losses The Guardian, Fiona Harvey, Dec 27, 2025.

Skeptical Science New Research for Week #52 2025

Posted on 25 December 2025 by Doug Bostrom, Marc Kodack

Open access notables

Satellite altimetry reveals intensifying global river water level variability, Fang et al., Nature Communications

River water levels (RWLs) are fundamental to hydrology, water resource management, and disaster mitigation, yet the majority of the world’s rivers remain ungauged. Here, using 46,993 virtual stations from Sentinel-3A/B altimetry (2016?2024), we present a global assessment of RWL variability. We find a median global fluctuation of 3.76 m, with pronounced spatial patterns: significant RWL declines across Central North/South America and Western Siberia, and increases across Africa, Oceania, Eastern/Southern Asia, and Northwestern/Central Europe. Seasonality is intensifying in 68% of basins, as high RWLs become more temporally concentrated. Maximum RWLs are declining by 0.88 cm/yr, while minimum RWLs are rising by 1.43 cm/yr. This convergence is reducing seasonal amplitude globally, with the most pronounced changes in the Americas and Central Africa. These shifts coincide with a recent surge in extreme RWL events, particularly after 2021, signaling growing hydrological instability amid concurrent droughts and floods. Our findings underscore the urgent need for adaptive water management in response to accelerating climate pressures.

Gazing into the flames: A guide to assessing the impacts of climate change on landscape fire, Clarke et al., Science Advances

Widespread impacts of landscape fire on ecosystems, societies, and the climate system itself have heightened the need to understand the potential future trajectory of fire under continued climate change. However, the complexity of fire makes climate change impact assessment challenging. The climate system influences fire in many ways, including through vegetation, fuel dryness, fire weather, and ignition. Furthermore, fire’s impacts are highly diverse, spanning threats to human and ecological values and beneficial ecosystem and cultural services. Here, we discuss the art and science of projecting climate change impacts on landscape fire. This not only includes how fire, its drivers, and its impacts are modeled, but critically it also includes how projections of the climate system are developed. By raising and discussing these issues, we aim to foster the development of more robust and useful fire projections, help interpret existing assessments, and support society in charting a course toward a sustainable fire future.

Observed positive feedback between surface ablation and crevasse formation drives glacier acceleration and potential surge, Nanni et al., Nature Communications

Sudden glacier acceleration and instability, e.g. surges, strongly influence glacier ice loss. However, lack of in-situ observations of the involved processes hampers our ability to understand, quantify and model such a role. We present an analysis of the initiation of a surge (Kongsvegen glacier, Svalbard), focusing on the interplay between climatic and glacier-specific drivers. We integrate two decades of in-situ observations (GNSS, borehole and surface seismometers) with runoff simulations, and remotely sensed surface-elevation changes. We show that initial glacier thinning led to localized acceleration and crevassing. Then, we show that stronger surface melt enabled meltwater to reach the glacier bed. This input promotes high basal water pressure and glacier sliding, and in turn further surface crevassing. Our observations suggest that this positive feedback leads to the expansion of the initially localized instability. Our findings highlight mechanisms that could trigger glacier instabilities under a warming atmosphere beyond the High Arctic.

Clinging to power: status threat and attitudes toward the renewable energy transition, Finnegan et al., Environmental Politics

Status threat, defined as the perception that one’s group status, influence, and position in the hierarchy are threatened, has been shown to impact public attitudes across a variety of issue areas. However, the role that status threat plays in forming attitudes on the renewable energy transition is unknown. Using an original survey experiment in the United States, we examine how status threat shapes attitudes toward the renewable energy transition. Our results suggest that status threat, particularly economic status threat, decreases support for renewable energy policies. Since attitudes toward the transition from a fossil fuel-based economy to one dominated by renewable energy remain mixed, our findings suggest that status threat may be directly hindering the renewable energy transition, which is central to efforts to combat climate change.

Who do we trust on climate change, and why?, Sheriffdeen et al., Climate and Development

Trust in climate communicators is a critical determinant of whether the public accepts and acts upon climate change information. Yet most research to date has focused on who is trusted, with less attention to why certain messengers are deemed trustworthy. Using survey data from 6479 participants across 13 countries, this study examines (1) which sources of climate information are trusted, (2) what features make a communicator trustworthy, and (3) how these judgments differ between climate change believers and skeptics. Scientists were the most trusted sources among climate believers, but overall, the most trusted sources are informal and identity-based: “friends and family” and “people like me.” Across the sample, trust was predicted not only by demographic variables but also by specific communicator features: most notably clarity, shared values, sincerity, and being respectful of opposing views. Believers and skeptics prioritized different features, underscoring that trust is not a universal response but shaped by ideological identity. These findings reveal the layered and audience-contingent nature of trust in climate communication. By identifying the features that drive trust across different audiences, this study offers practical guidance for communicators interested in tailoring messages and messengers to more effectively engage the public on climate action.

From this week's government/NGO section:

Climate Science and Natural Resource Litigation, Jessica Wentz, Columbia Law School, Sabin Center for Climate Change Law

Climate change has major implications for sustainable use and conservation of natural resources. Many natural systems are already under severe stress and may be unable to sustain historical use patterns; resource management decisions can also exacerbate or mitigate climate change by affecting the balance of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. The author describes the legal and scientific basis for recognizing agencies’ obligations to assess and respond to climate change, drawing insights from a survey of U.S. litigation involving forests, fisheries, rangelands, and freshwater resources. Litigants have been somewhat successful in driving more rigorous assessments of climate change. However, agencies still frequently conclude that climate impacts are too uncertain or insignificant to warrant a response, and courts will generally defer unless the agency has overlooked or arbitrarily dismissed actionable scientific information. This underscores the importance of collaboration among resource managers, legal advocates, and scientists to develop, disseminate, and communicate scientific information that can meaningfully inform these decisions.

Climate Change in the American Mind: Politics & Policy, Fall 2025, Leiserowitz et al., Yale University and George Mason University

With the first primaries in the 2026 midterm elections just around the corner, the authors found that the economy and the cost of living are the top two issues registered voters say will be “very important” when they decide who they will vote for in the 2026 congressional elections (79% and 78%, respectively). In this context, they also found that 65% of registered voters think global warming is affecting the cost of living in the United States. 49% say policies intended to transition away from fossil fuels and toward clean energy will improve economic growth and provide new jobs (versus 27% who think they will reduce economic growth and cost jobs).

105 articles in 49 journals by 551 contributing authors

Physical science of climate change, effects

Are Trends of Gulf Stream Transport Uniform Along the Florida Shelf?, Torres?Córdoba & Valle?Levinson, Geophysical Research Letters Open Access 10.1029/2025gl118418

Drying Tropical America Under Global Warming: Mechanism and Emergent Constraint, He et al., Geophysical Research Letters Open Access 10.1029/2025gl117131

How climate change broke the Pacific Northwest’s plumbing

Posted on 24 December 2025 by Guest Author

This is a re-post from The Climate Brink by Andrew Dessler

Flooding in the Pacific Northwest (PNW) has recently turned deadly serious, as days of intense rain from a powerful atmospheric river have swollen rivers and caused widespread flooding across the PNW.

Here is why:

1. The atmosphere is wetter

The first mechanism is the one you hear about most often: basic thermodynamics. The rule of thumb (the Clausius-Clapeyron relation for the science geeks) is that for every degree Celsius the atmosphere warms, it can hold about 7% more water vapor.

If the atmosphere is a sponge, then a warmer atmosphere is a bigger sponge. This allows the atmospheric river that carries water from the Pacific to soak up more moisture from oceans that are also warmer than average. When that “sponge” hits the Cascades or Olympics and gets wrung out, there is simply more water available to fall than there was in the past.

Because of this, the IPCC says: “Human influence has contributed to the intensification of heavy precipitation in three continents where observational data are more abundant (high confidence) (North America, Europe and Asia).” [IPCC AR6 WG1, Section 11.4.4].

2. The Phase Shift: Rain vs. Snow

This is another critical factor for the PNW. In the cooler 20th-century, much of the precipitation hitting the Cascades or Olympics would fall as snow. Snow is safe. Snow sits there. It accumulates without drama, effectively “banking” water for the spring and summer months when it is needed most.

However, as freezing levels rise due to warming temperatures, precipitation is increasingly falling as rain. Unlike snow, rain does not sit quietly in the mountains and wait for spring. It runs off immediately.

So when a storm dumps 10 inches of precipitation and half of it falls as snow, the rivers only have to handle 5 inches of water immediately. But if all of it falls as rain because it’s 45°F in the mountains, the rivers have to handle the full 10 inches right now. This climate-enhanced runoff can overwhelm the river system, leading to the widespread flooding we see now.

Fact brief - Do solar panels generate more waste than fossil fuels?

Posted on 23 December 2025 by Sue Bin Park

![]() Skeptical Science is partnering with Gigafact to produce fact briefs — bite-sized fact checks of trending claims. You can submit claims you think need checking via the tipline.

Skeptical Science is partnering with Gigafact to produce fact briefs — bite-sized fact checks of trending claims. You can submit claims you think need checking via the tipline.

Do solar panels generate more waste than fossil fuels?

Waste from discarded solar panels is dwarfed by the waste from coal, oil, and gas. In addition, solar panel recycling capacity continues to expand and improve.

Waste from discarded solar panels is dwarfed by the waste from coal, oil, and gas. In addition, solar panel recycling capacity continues to expand and improve.

A 2023 study estimated that from 2016 – 2050, if power systems do not decarbonize, coal ash would be 300 – 800 times heavier than waste from discarded solar panels, and oily sludge from fossil fuels would be 2 – 5 times heavier.

Currently only about 10 – 15% of panels are recycled in the U.S., but governments and companies are funding additional research and new facilities. Existing plants can already recover around 90 – 95% of a panel’s mass, including glass, aluminum, and steel, and up to 95 – 97% of key semiconductor materials such as cadmium and tellurium.

As solar grows, recycling will cut waste and emissions further, while the bigger waste problem comes from not replacing fossil fuels.

Go to full rebuttal on Skeptical Science or to the fact brief on Gigafact

This fact brief is responsive to quotes such as this one.

Sources

U.S. Department of Energy Photovoltaic Toxicity and Waste Concerns Are Overblown, Slowing Decarbonization--NREL Researchers Are Setting the Record Straight

The Washington Post Scientists found a solution to recycle solar panels in your kitchen

Solar Energy Solar photovoltaic recycling strategies

Nature Energy Research and development priorities for silicon photovoltaic module recycling to support a circular economy

Energy Strategy Reviews An overview of solar photovoltaic panels’ end-of-life material recycling

Columbia Law School Sabin Center for Climate Change Law Rebutting 33 False Claims About Solar, Wind, and Electric Vehicles

Please use this form to provide feedback about this fact brief. This will help us to better gauge its impact and usability. Thank you!

Zeke's 2026 and 2027 global temperature forecasts

Posted on 22 December 2025 by Zeke Hausfather

This is a re-post from The Climate Brink

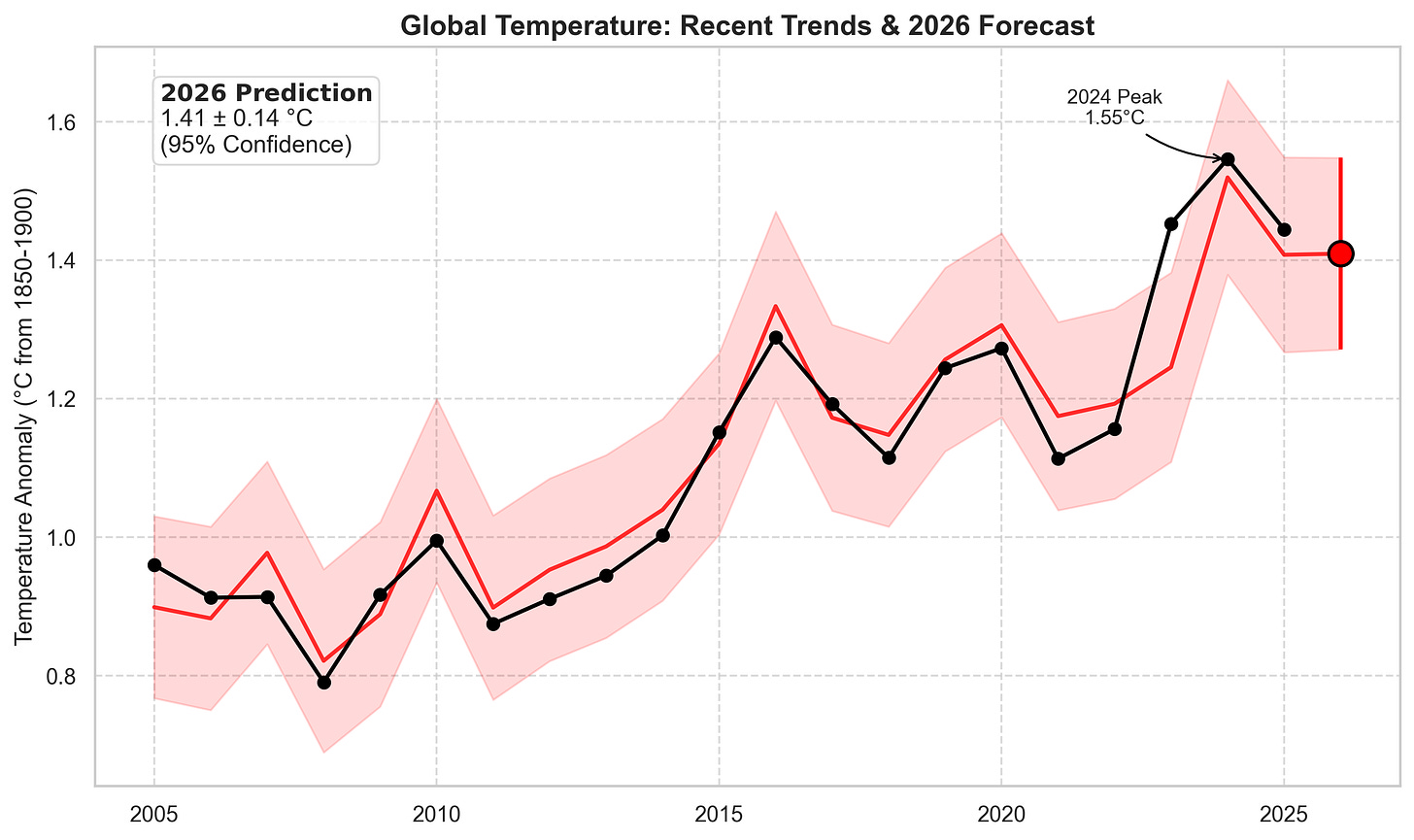

Tis the season for global temperature forecasts. The UK Met Office recently released their 2026 prediction, estimating that it is most likely to end up as the second warmest year on record at 1.46C (with a range of 1.34C and 1.58C) relative to the 1850-1900 preindustrial baseline period.1 This is likely warmer than both 2023 and 20252 and with a small chance of being warmer than 2024.

Not to be outdone, James Hansen released his estimate that 2026 temperatures will also be around 1.47C in the GISTEMP dataset (albeit using a somewhat different 1880-1920 baseline)3, with the 12 month average dipping down to around 1.4C in the coming months before rising back up by year’s end.

Hansen also adds a prediction for 2027 at 1.7C (1.65C to 1.75C), albeit with the caveat that this refers to the peak 12-month warming during the year rather than the annual average. The prediction is based on an assumed El Nino developing in late 2026 – something that models have suggested is increasingly likely in recent weeks.

I’ve long done year-ahead predictions of global mean surface temperatures (included in the Carbon Brief annual state of the climate report). I base it on a linear regression model that uses a year count, the prior year’s temperature, the latest monthly temperature, and the predicted ENSO (El Nino / La Nina) conditions of the first three months of the coming year, as these factors tend to be the most predictive historically.

The model is fit on historical data since 19704 using the WMO average of six datasets,5 and I’ve slightly tweaked the model this year to include a squared term for the year count to ensure it is not forced to be too linear (though the effects of this change are minor).

For 2026 I expect global temperatures to be around around 1.41C, with a 95% confidence interval of 1.27C to 1.55C. This means that it is almost certain to be one of the top-4 warmest years, but quite unlikely to exceed 2024’s record. Global temperatures in 2026 will be slightly suppressed by modest La Nina conditions in the tropical Pacific early in the year, while a late-developing El Nino (if it occurs) will primarily affect 2027 temperatures.

2025 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming News Roundup #51

Posted on 21 December 2025 by BaerbelW, Doug Bostrom

Story of the week

As you can see below, five of the six articles in the Climate Policy and Politics category are about the plans to dismantle the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) in Boulder, Colorado. If you live in the US and would like to speak out against this ill-advised plan, you can do so via the action page provided by AGU, the American Geophysical Union: Speak Out to Save NCAR today!

Stories we promoted this week, by category:

Climate Policy and Politics (6 articles)

- Oil executives once booed Canada`s prime minister. Now they cheer him. Mark Carney, once a U.N. special envoy on climate action and finance, is now winning praise from industry but alienating former environmental allies. World, Amanda Coletta, Dec 13, 2025.

- National Center for Atmospheric Research to Be Dismantled, Trump Administration Says Russell Vought, the White House budget director, called the laboratory a source of “climate alarmism.” NYT > Science, Lisa Friedman, Brad Plumer and Jack Healy, Dec 17, 2025.

- Trump administration announces plans to `break up` the National Center for Atmospheric Research The center is one of the world’s premier institutions for studying the atmosphere. Its work has saved countless lives. Yale Climate Connections, Bob Henson and Jeff Masters, Dec 17, 2025.

- We`re all at risk if Trump dismantles this legendary lab Breaking up the National Center for Atmospheric Research would be a "genuinely shocking self-inflicted wound." Grist, Matt Simon, Dec 18, 2025.

- The U.S. Is on the Verge of Meteorological Malpractice The Trump administration says it will dismantle a premier climate center, while somehow keeping weather forecasting intact. The Atlantic, Michelle Nijhuis, Dec 18, 2025.

- Threatening NCAR, Trump administration seeks to extinguish a beacon of climate science The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Benjamin Santer, Dec 19, 2025.

Climate Change Impacts (5 articles)

- Guest post: How the Greenland ice sheet fared in 2025 Greenland is closing in on three decades of continuous annual ice loss, with 1995-96 being the last year in which the giant ice sheet grew in size. Carbon Brief, Dr Martin Stendel and Prof Ruth Mottram, Dec 15, 2025.

- TCB quick hit: How climate change broke the Pacific Northwest`s plumbing It’s not just wetter storms—it’s also the important shift from snow to rain The Climate Brink, Andrew Dessler, Dec 15, 2025.

- Record-breaking climate change: 2025 edition Dr Gilbz on Youtube, Ella Gilbert, Dec 15, 2025.

- Arctic endured year of record heat as climate scientists warn of `winter being redefined` Region known as ‘world’s refrigerator’ is heating up as much as four times as quickly as global average, Noaa experts say The Guardian, Oliver Milman, Dec 16, 2025.

- Canada's North is warming from the ground up, and our infrastructure isn't ready The Conversation, Mohammadamin Ahmadfard, Ibrahim Ghalayini, Seth Dworkin, Dec 17, 2025.

Skeptical Science New Research for Week #51 2025

Posted on 18 December 2025 by Doug Bostrom, Marc Kodack

Open access notables

Widespread Increase in Atmospheric River Frequency and Impacts Over the 20th Century, Scholz & Lora, AGU Advances

Atmospheric rivers (ARs) play a dominant role in water resource availability in many regions, and can cause substantial hazards, including extreme precipitation, flooding, and moist heatwaves. Despite this, there is substantial uncertainty about recent and ongoing changes in AR frequency and impacts. Here, we place recent observed trends in their longer-term context using AR records extending back to 1940. Our results show that AR frequency has increased broadly across the midlatitudes, bridging the apparent discrepancy between the observed satellite-era poleward shift and the general increase simulated in climate change projections. This increase in AR frequency enhances AR-associated precipitation and snowfall across their region of influence in the mid- and high-latitudes. We also find that, despite warmer surface temperatures associated with ARs, there is a decrease in the magnitude of AR-associated temperature anomalies in high-latitude regions due to Arctic amplification. An increase in AR-associated humid heatwaves underscores the societal importance of changing AR activity.

Reduction of Residence Time of Air in the Arctic Since the 1980s, Plach et al., Geophysical Research Letters

The Arctic has seen dramatic changes in recent decades. Here we use a simple metric, the Arctic residence time of air, that is, the time air spends uninterruptedly north of 70N, to evaluate how these changes have affected the high-latitude atmospheric circulation in the last 40 years. We find that, on average, near-surface air resides between 7 (winter) and 12 (summer) days in the Arctic. This residence time has decreased almost year-round since the 1980s, especially pronounced in the seasonal transition periods (fall: 0.9 days; spring: 1.4 days). The more pronounced reduction in spring also affects higher atmospheric layers. Our analysis indicates that this reduction is likely linked to the observed sea ice loss, decrease in snow cover, and increase in temperature. Furthermore, it indicates a speed-up of the circulation, effectively making the Arctic less isolated and more prone to influences from mid-latitudes.

Peak glacier extinction in the mid-twenty-first century, Van Tricht et al., Nature Climate Change

Projections of glacier change typically focus on mass and area loss, yet the disappearance of individual glaciers directly threatens culturally, spiritually and touristically significant landscapes. Here, using three global glacier models, we project a sharp rise in the number of glaciers disappearing worldwide, peaking between 2041 and 2055 with up to ~4,000 glaciers vanishing annually. Regional variability reflects differences in average glacier size, local climate, the magnitude of warming and inventory completeness.

Countering the Climate Change Counter Movement: Six lessons from Canada's climate delays, Lloyd & Rhodes, Energy Research & Social Science

The global transition away from fossil fuels is dangerously delayed. While climate delays are a complex issue, the fossil-fuel funded Climate Change Counter Movement represents a key culprit that is worthy of greater attention than it receives. As such, this article uses Canada as a case study to highlight the Movement's role in delaying climate action in the West, and to suggest six strategies to counteract their influence. We collate evidence demonstrating the Climate Change Counter Movement's influence over the Canadian state, its economy and its people, and directly linking elite members of the Movement to post-truth narratives that deny the reality of climate change, and delay climate policy. Concerningly, we also find evidence that these “climate delay discourses” can rapidly evolve to exploit new contexts and cultures, and are already being repeated by unassociated members of the general public. In order to spur action against the Climate Change Counter Movement, we combine insights from our case study with a narrative review of international research to suggest six strategies to counteract their influence, alongside associated directions for future research. These strategies would see climate policy advocates: reflect upon their own position; develop knowledge of the Climate Change Counter Movement's actions; use that knowledge to hold them legally accountable for those actions; reverse the effects they have already had on the general population; push “passively supported” policies to advance climate action even when public appetites are low; and challenge the economic and cultural roots of the Climate Change Counter Movement's power.

From this week's government/NGO section:

Arctic Report Card 2025, Druckenmiller et al., National Oceanic and Atmospheric Organization

Now in its 20th year, the Arctic Report Card (ARC) 2025 provides a clear view of a region warming far faster than the rest of the planet. Along with reports on the state of the Arctic’s atmosphere, oceans, cryosphere, and tundra, this year’s report highlights major transformations underway—atlantification bringing warmer, saltier waters northward, boreal species expanding northward into Arctic ecosystems, and “rivers rusting” as thawing permafrost mobilizes iron and other metals. Across these changing landscapes, sustained observations and strong research partnerships, including those led by communities and Indigenous organizations, remain essential for understanding and adaptation.

Big Oil’s Deceptive Climate Ads. How Four Oil Majors Sold False Promises from 2000-2025, Charlotte Marcil, Center for Climate Integrity

While knowingly fueling the climate crisis, four oil majors — BP, Chevron, ExxonMobil, and Shell — spent 25 years running deceptive advertising campaigns to falsely reposition themselves as partners in the fight against climate change. The author examines more than 300 unique climate-related advertisements across seven categories of deception, highlighting Big Oil’s modern campaign of lies.

125 articles in 52 journals by 826 contributing authors

Physical science of climate change, effects

Contributions of Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation, Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation, and global oceanic warming to the secular change in United States tornado occurrence, Zhao et al., Atmospheric Research 10.1016/j.atmosres.2025.108689

Large Uncertainty in Arctic Warming Driven by the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, Hahn et al., Geophysical Research Letters Open Access 10.1029/2025gl119720

What are the causes of recent record-high global temperatures?

Posted on 17 December 2025 by Zeke Hausfather

This is a re-post from Carbon Brief

The past three years have been exceptionally warm globally.

In 2023, global temperatures reached a new high, after they significantly exceeded expectations.

This record was surpassed in 2024 – the first year where average global temperatures were 1.5C above pre-industrial levels.

Now, 2025 is on track to be the second- or third-warmest year on record.

What has caused this apparent acceleration in warming has been subject to a lot of attention in both the media and the scientific community.

Dozens of papers have been published investigating the different factors that could have contributed to these record temperatures.

In 2024, the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) discussed potential drivers for the warmth in a special section of its “state of the global climate” report, while the American Geophysical Union ran a session on the topic at its annual meeting.

In this article, Carbon Brief explores four different factors that have been proposed for the exceptional warmth seen in recent years. These are:

- A strong El Niño event that developed in the latter part of 2023.

- Rapid declines in sulphur dioxide emissions – particularly from international shipping and China.

- An unusual volcanic eruption in Tonga in 2022.

- A stronger-than-expected solar cycle.

Carbon Brief’s analysis finds that a combination of these factors explains most of the unusual warmth observed in 2024 and half of the difference between observed and expected warming in 2023.

However, natural fluctuations in the Earth’s climate may have also played a role in the exceptional temperatures, alongside signs of declining cloud cover that may have implications for the sensitivity of the climate to human-caused emissions.

Fact brief - Are toxic heavy metals from solar panels posing a threat to human health?

Posted on 16 December 2025 by Sue Bin Park

![]() Skeptical Science is partnering with Gigafact to produce fact briefs — bite-sized fact checks of trending claims. You can submit claims you think need checking via the tipline.

Skeptical Science is partnering with Gigafact to produce fact briefs — bite-sized fact checks of trending claims. You can submit claims you think need checking via the tipline.

Are toxic heavy metals from solar panels posing a threat to human health?

Toxic heavy metals in solar panels are locked in stable compounds and sealed behind tough glass, preventing escape into air, water, or soil at harmful levels.

Toxic heavy metals in solar panels are locked in stable compounds and sealed behind tough glass, preventing escape into air, water, or soil at harmful levels.

Most concern focuses on cadmium and lead. 40% of new U.S. panels use cadmium telluride, which does not dissolve in water, easily turn to gas, or approach the toxicity of pure cadmium.

During manufacturing and disposal, heavy metals are handled under safety and waste rules. Per unit of electricity, solar releases far less heavy metals than fossil fuels.

Studies and safety reviews find that heavy metals pose no qualifiable danger to health during the regular manufacture, use, or regulated disposal of solar panels.

Go to full rebuttal on Skeptical Science or to the fact brief on Gigafact

This fact brief is responsive to quotes such as this one.

Sources

NREL Polycrystalline Thin-Film Research: Cadmium Telluride

NC Clean Energy Technology Center Health and Safety Impacts of Solar Photovoltaics

American Chemical Society Emissions from Photovoltaic Life Cycles

EPA Solar Panel Frequent Questions

Massachusetts Department of Energy Resources Questions & Answers: Ground-Mounted Solar Photovoltaic Systems

EPA Ecological Soil Screening Level

Columbia Law School Sabin Center for Climate Change Law Rebutting 33 False Claims About Solar, Wind, and Electric Vehicles

Please use this form to provide feedback about this fact brief. This will help us to better gauge its impact and usability. Thank you!

Emergence vs Detection & Attribution

Posted on 15 December 2025 by Ken Rice

This is a re-post from And Then There's Physics

Since effective communication often involves repeating things, I thought I would repeat what others have pointed out already. The underlying issue is that there is a narrative in the climate skeptosphere suggesting that extreme weather events are not becoming more common, or that we can’t yet attribute changes in most extreme weather types to human influences (as suggested in the recent DoE climate report).

This is often based on the Table shown on the right, taken from Chapter 12 of the IPCC AR6 WGI report. As, I think, originally pointed out by Tim Osborn, this table is not suggesting that we haven’t yet detected changes in most extreme weather events, or haven’t managed to attribute a human influence. It’s essentially considering if, or when, a signal has/will have emerged from the noise. Formally, emergence is defined as the magnitude of a particular event increasing by more than 1 standard deviation of the normal variability.

2025 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming News Roundup #50

Posted on 14 December 2025 by BaerbelW, Doug Bostrom

Stories we promoted this week, by category:

Climate Change Impacts (8 articles)

- When climate risk hits home, people listen: Local details can enhance disaster preparedness messaging Phys.org, Stockholm School of Economics, Dec 08, 2025.

- A 30-year-old sea level rise projection has basically come true Even without today’s advanced modeling tools, scientists made a ‘remarkably’ accurate estimate. Yale Climate Connections, YCC Team, Dec 08, 2025.

- Nearly 8,000 animal species are at risk as extreme heat and land-use change collide Phys.org, University of Oxford, Dec 09, 2025.

- 2025 `virtually certain` to be second- or third-hottest year on record, EU data shows Copernicus deputy director says three-year average for 2023 to 2025 on track to exceed 1.5C of heating for first time The Guardian, Ajit Niranjan, Dec 09, 2025.

- Global warming amplifies extreme day-to-day temperature swings, study shows Phys.org, Li Yali, Dec 10, 2025.

- 3rd warmest on record (again): November 2025 keeps a hot global streak going This year is likely to end up as the 2nd- or 3rd-warmest year on record, despite the lack of a planet-warming El Niño event. Yale Climate Connections, Jeff Masters and Bob Henson, Dec 11, 2025.

- Climate change is stealing rain and snow from the Colorado River, new report says Global weirding all across the board; while the US PNW reels under juiced-up atmospheric rivers, the SW US is dessicating as predicted by climate models. The Colorado Sun, Katie Hawkinson , Dec 12, 2025.

- In Alaska`s warming Arctic, photos show an Indigenous elder passing down hunting traditions An Inupiaq elder teaches his great-grandson to hunt in rapidly warming Northwest Alaska where thinning ice, shifting caribou migrations and severe storms are reshaping life The Independent News, Annika Hammerschlag, Dec 13, 2025.

Climate Policy and Politics (5 articles)

- As natural disasters tear through Asia, politicians ignore climate at their own peril ABC News, Karishma Vyas, Dec 06, 2025.

- The EPA is wiping mention of human-caused climate change from its website Some pages have been tweaked to emphasize ‘natural forces’; others have been deleted entirely. Washington Post, Shannon Osaka, Dec 9, 2025.

- EPA eliminates mention of fossil fuels in website on warming's causes. Scientists call it misleading Phys.org, Seth Borenstein, Dec 10, 2025.

- The EPA website got the basics of climate science right. Until last week. The Trump administration purged 80 pages of facts about climate change — including that it's caused by humans Grist, Kate Yoder, Dec 11, 2025.

- Climate change is straining Alaska's Arctic. A new mining road may push the region past the brink In Northwest Alaska, a proposed 211-mile mining road has divided an Inupiaq community already devastated by climate change The Independent News, Annika Hammerschlag, Dec 11, 2025.

Skeptical Science New Research for Week #50 2025

Posted on 11 December 2025 by Doug Bostrom, Marc Kodack

Open access notables

Detectability of Post-Net Zero Climate Changes and the Effects of Delay in Emissions Cessation, King et al., Earth's Future

There is growing interest in how the climate would change under net zero carbon dioxide emissions pathways as many nations aim to reach net zero in coming decades. In today's rapidly warming world, many changes in the climate are detectable, even in the presence of internal variability, but whether climate changes under net zero are expected to be detectable is less well understood. Here, we use a set of 1000-year-long net zero carbon dioxide emissions simulations branching from different points in the 21st century to examine detectability of large-scale, regional and local climate changes as time passes under net zero emissions. We find that even after net zero, there are continued detectable changes to climate for centuries. While local changes and changes in extremes are more challenging to detect, Southern Hemisphere warming and Northern Hemisphere cooling become detectable at many locations within a few centuries under net zero emissions. We also study how detectable delays in achieving emissions cessation are across climate indices. We find that for global mean surface temperature and other large-scale indices, such as Antarctic and Arctic sea ice extent, the effects of an additional 5 years of high greenhouse gas emissions are detectable. Such delays in emissions cessation result in significantly different local temperatures for most of the planet, and most of the global population. The long simulations used here help with identifying local climate change signals. Multi-model frameworks will be useful to examine confidence in these changes and improve understanding of post-net zero climate changes.

From short-term uncertainties to long-term certainties in the future evolution of the Antarctic Ice Sheet, Coulon et al., Nature Communications

Robust projections of future sea-level rise are essential for coastal adaptation, yet they remain hampered by uncertainties in Antarctic ice-sheet projections–the largest potential contributor to sea-level change under global warming. Here, we combine two ice-sheet models, systematically sample parametric and climate uncertainties, and calibrate against historical observations to quantify Antarctic ice-sheet changes to 2300 and beyond. By 2300, the projected Antarctic sea-level contributions range from -0.09 m to +1.74 m under low emissions (SSP1-2.6, outer limits of 5-95% probability intervals), and from +0.73 m to +5.95 m under very high emissions (SSP5-8.5). Irrespective of the wide range of uncertainties explored, large-scale Antarctic ice-sheet retreat is triggered under SSP5-8.5, while reaching net-zero emissions well before 2100 strongly reduces multi-centennial ice loss. Yet, even under such strong mitigation, a significant sea-level contribution could still result from West Antarctica. Our results suggest that current mitigation efforts may not be sufficient to avoid self-sustained Antarctic ice loss, making emission decisions taken in the coming years decisive for future sea-level rise.

Declining number of northern hemisphere land-surface frozen days under global warming and thinner snowpacks, Hatami et al., Communications Earth & Environment

Freeze–thaw processes shape ecosystems, hydrology, and infrastructure across northern high latitudes. Here we use satellite-based observations from 1979–2021 across 47 northern hemisphere ecoregions to examine changes in the number of frozen land-surface days per year. We find widespread declines, with 70% of ecoregions showing significant reductions, primarily linked to rising air temperatures and thinning snowpacks. Causal analysis demonstrates that air temperature and snow depth exert consistent controls on the number of frozen days. A trend-informed assessment based on historical observations suggests a potential average loss of more than 30 frozen days per year by the end of the century, with the steepest decreases in Alaska, northern Canada, northern Europe, and eastern Russia. Scenario-based analysis indicates that each 1 °C increase in air temperature reduces frozen days by ~6-days, while each 1 cm decrease in snow depth leads to a ~ 3-day reduction. These shifts carry major ecological and socio-economic implications.

Timing of a future glaciation in view of anthropogenic climate change, Kaufhold et al., Communications Earth & Environment

Human activities are expected to delay the next glacial inception because of the long atmospheric lifetime of anthropogenic CO2. Here we present Earth system model simulations for the next 200,000 years with dynamic ice sheets and interactive atmospheric CO2, exploring how emissions will impact a future glacial inception. Historical emissions (500 PgC) are unlikely to delay inception, expected to occur under natural conditions around 50,000 years from now, while a doubling of current emissions (1000 PgC) would delay inception for another 50,000 years. Inception is generally expected within the next 200,000 years for emissions up to 5000 PgC. Our model results show that assumptions about the long-term balance of geological carbon sources and sinks has a strong impact on the timing of the next glacial inception, while millennial-scale variability in the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation influences the exact timing. This work highlights the long-term impact of anthropogenic CO2 on climate.

From this week's government/NGO section:

Extreme Heat and the Shrinking Diurnal Range. A Global Evaluation of Oppressive Air Mass Character and Frequency, Kalkstein et al., Climate Resilience for All

As country leaders focus on avoiding breaching the +1.5°C threshold of the Paris Agreement, nighttime temperatures in cities are soaring at a rate of as much as 10 times higher than daytime temperatures. The authors examine how nighttime temperatures are rising at alarming rates in cities across the globe. The authors found that cities are not only experiencing on average an extra day of extreme heat every six years, but also—even more alarmingly—nighttime temperatures are rising much more rapidly than daytime highs in a majority of the cities worldwide. Women are particularly vulnerable to nighttime heat. Physiological factors make them more sensitive to higher temperatures, and societal norms and inequalities amplify their risk. Often shouldering a greater burden of care for older relatives and the sick, it is usually a woman who stays awake when their family member cannot sleep, sacrificing her own rest and recovery, to care for them. And gender norms, or the threat of violence can keep women from sleeping outside or with windows open, making thermal relief even harder to find.

Extreme Heat, Gender and Health - A dialogue towards climate resilient adaptation, Kumar et al., Multiple

India's rapidly growing cities are becoming dangerous for pregnant women as extreme heat combines with inadequate housing and fragmented health systems to create life-threatening conditions. The Heat in Pregnancy – India (HiP-I) project brought together leading experts to examine this escalating crisis and identify urgent solutions. Policies must be tailored to local realities. India-specific research is necessary to understand the impact of heat on pregnancy, and early warning systems should incorporate humidity and nighttime temperatures, rather than focusing solely on peak daytime heat. Coordination across sectors is essential. Governance fragmentation leaves pregnant women in informal settlements without protection, while urban planning, health systems, water management, and housing policy continue to operate in silos. Breaking these silos is key to effective adaptation.

Highlights from the extreme heat and agriculture report, Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations and the World Meteorological Organization

The authors explore the impact of extreme heat on agricultural producers and on crops, livestock, fisheries and aquaculture, and forests worldwide. Drawing on recent scientific evidence and country case studies, they highlight the independent and compound risks posed by extreme heat, underscores the urgency of mitigation, and presents pathways to strengthen resilience and sustainability across agricultural sectors.

135 articles in 58 journals by 831 contributing authors

Physical science of climate change, effects

Antarctic Bottom Water in a changing climate, Jacobs, Nature Reviewss Earth & Environment, 10.1038/s43017-025-00750-2

Hot droughts in the Amazon provide a window to a future hypertropical climate, Chambers et al., Nature 10.1038/s41586-025-09728-y

Arguments

Arguments

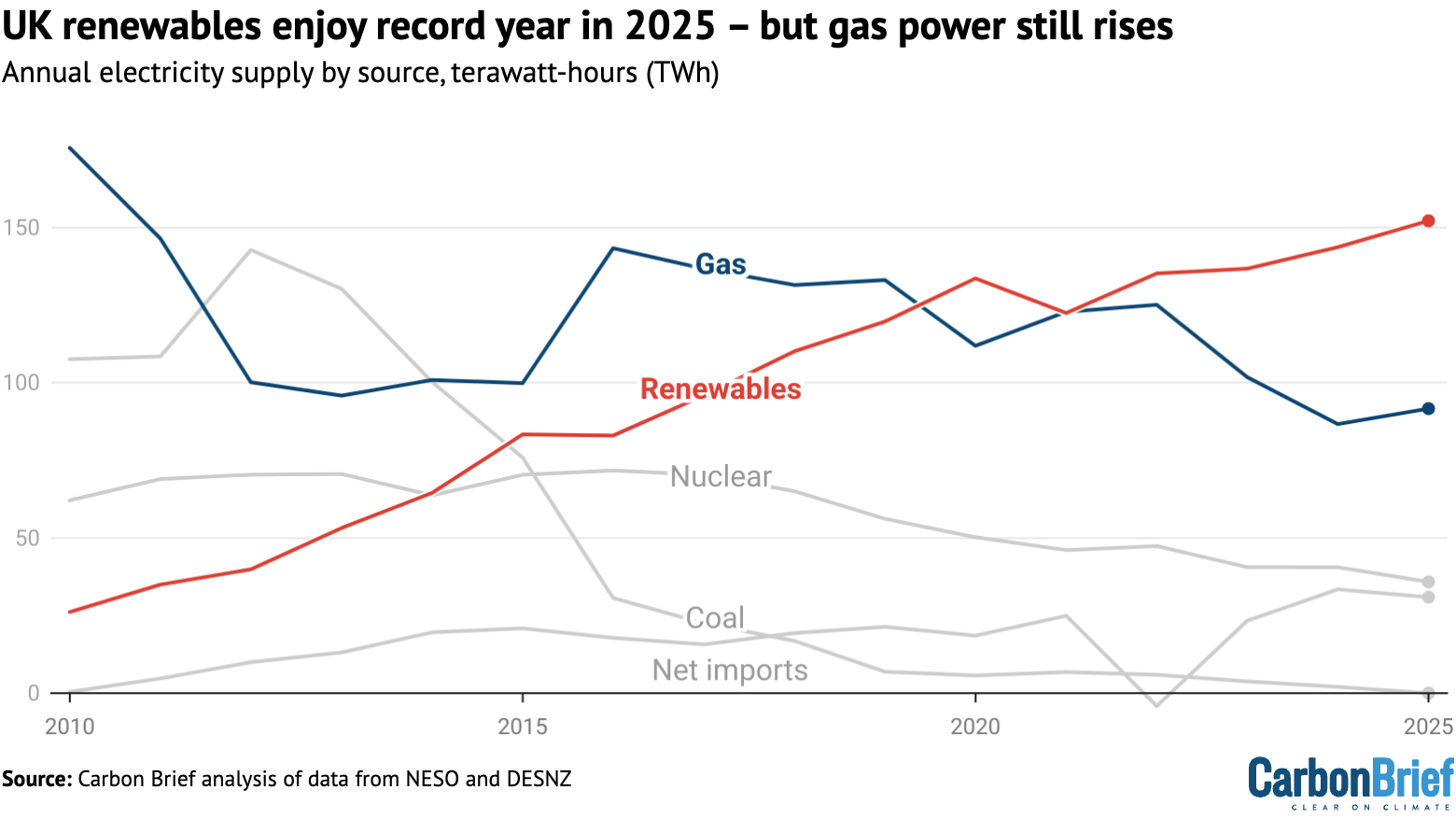

UK electricity supplies by source 2010-2025, terawatt hours (TWh). Net imports are the sum of imports minus exports. Renewables include wind, biomass, solar and hydro. The chart excludes minor sources, such as oil, which makes up less than 2% of the total. Source: Carbon Brief analysis of data from NESO and DESNZ.

UK electricity supplies by source 2010-2025, terawatt hours (TWh). Net imports are the sum of imports minus exports. Renewables include wind, biomass, solar and hydro. The chart excludes minor sources, such as oil, which makes up less than 2% of the total. Source: Carbon Brief analysis of data from NESO and DESNZ.