[Haz clic aquí para leer en español]

It has a population of just under 3.5 million inhabitants, produces nearly 550,000 tons of beef per year, and boasts a glorious soccer reputation with two World Cups in its history and a present full of world-class stars. Uruguay, the country of writer Mario Benedetti and soccer player Luis Suárez, has achieved what many countries have pledged for decades: 98% of its grid runs on green energy.

Luis Prats, 62, is a Uruguayan journalist and contributor to the Montevideo newspaper El País. He remembers that during his childhood, blackouts were common in Uruguay because there were major problems with energy generation.

“At that time, more than 50 years ago, electricity came from two small dams and from generation in a thermal plant,” Prats explained in Spanish by telephone. “If there was a drought in the Negro River basin, where those dams are, there were already cuts and sometimes restrictions on the use of electrical energy.”

Just 17 years ago, Uruguay used fossil fuels for a third of its energy generation, according to the World Resources Institute.

Today, only 2% of the electricity consumed in Uruguay is generated from fossil sources. The country’s thermal power plants rarely need to be activated, except when natural resources are insufficient.

Half of Uruguay’s electricity is generated in the country’s dams, and 10% percent comes from agricultural and industrial waste and the sun. But wind, at 38%, is the main protagonist of the revolution in the electrical grid. But how did the country achieve it? Who were the architects of this energy transition?

2024 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming News Roundup #51

Posted on 22 December 2024 by BaerbelW, Doug Bostrom, John Hartz

Based on feedback we received, this week's roundup is the first one published soleley by category. We are still interested in feedback to hone the categorization, so if you spot any clear misses and/or have suggestions for additional categories, please let us know in the comments. Thanks!

Stories we promoted this week, by category:

Climate Change Impacts

- How much should you worry about a collapse of the Atlantic conveyor belt? Scientists warned recently that the risk “has so far been greatly underestimated.” by Bob Henson, Yale Climate Connections, Dec 11, 2024

- Shrinking wings, bigger beaks: Birds are reshaping themselves in a warming world by Sara Ryding, Alexandra McQueen and Matthew Symonds, Phys.org - reposted from The Conversation, Dec 16, 2024

- New data shows just how bad the climate insurance crisis has become Two congressional reports make clear that, with increasingly frequent hurricanes, floods, and fires, "the model of insurance as it stands right now isn't working." by Tik Root, Grist, Dec 19, 2024

Climate Law and Justice

- New Report Shows a Surge in European SLAPP Suits as Fossil Fuel Industry Works to Obstruct Climate Action But experts say these “abusive” lawsuits, which are designed to demoralize and drain resources from activists, should be fought, not feared. by Stella Levantesi, DeSmog, Dec 17, 2024

- Montana top court upholds landmark youth climate ruling Montana's Supreme Court upholds a lower court's decision siding with 16 youngsters arguing that the state violated their right to a clean environment. by Max Matza, BBC News, Dec 19, 2024

- Montana Supreme Court backs youth plaintiffs in groundbreaking climate trial by Ellis Juhlin, NPR - Montana Public Radio, Dec 18, 2024

Climate Policy and Politics

- Anxious scientists brace for Trump`s climate denialism: `We have a target on our backs` Experts express fear – and resilience – as they prepare for president-elect’s potential attacks on climate research by Oliver Milman, The Guardian, Dec 15, 2024

- 6 Fracking Billionaires and Climate Denial Groups Behind Trump`s Cabinet Trump’s nominees are backed by major players in the world of climate obstruction – from Project 2025 and Koch network fixtures to oil-soaked Christian nationalists. by Joe Fassler, DeSmog, Dec 16, 2024

- A new podcast explores the `hot mess` of climate politics Podcast from Citizen's Climate Lobby talks about how the world of climate facts bridges political divides. by Flannery Winchester, Citizens' Climate Lobby, Dec 18, 2024

- Tim Ryan is a paid fossil fuel mouthpiece Creating an atmosphere of confusion is a well-rewarded job of work, according to this article. by Emily Atkin, HEATED, Dec 12, 2024

- Carbon tax had 'negligible' impact on inflation, new study says University of Calgary professors find that prices are only 0.5% higher due to carbon tax and other measures by Peter Zimonjic, Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, Dec 12, 2024

- Nigel Farage Helps to Launch U.S. Climate Denial Group in UK The Heartland Institute, which questions human-made climate change, has established a new branch in London by Sam Bright, DeSmog, Dec 19, 2024

Fact brief - Are we heading into an 'ice age'?

Posted on 21 December 2024 by Guest Author

![]() Skeptical Science is partnering with Gigafact to produce fact briefs — bite-sized fact checks of trending claims. This fact brief was written by Sue Bin Park from the Gigafact team in collaboration with members from our team. You can submit claims you think need checking via the tipline.

Skeptical Science is partnering with Gigafact to produce fact briefs — bite-sized fact checks of trending claims. This fact brief was written by Sue Bin Park from the Gigafact team in collaboration with members from our team. You can submit claims you think need checking via the tipline.

Note: Technically we are currently in an ice age (there is ice at the poles) and what we're really discussing here is the glacial cycle. We are in an inter-glacial and the question is if we could be heading for another glacial period. However, since the myth typically refers to this as an "ice age", we decided to stick with that term.

Are we heading into an ‘ice age’?

The planet has been getting warmer since the Industrial Revolution, not colder.

The planet has been getting warmer since the Industrial Revolution, not colder.

Historically, ice ages have followed changes in the Earth’s relationship to the sun. Natural cycles affect the tilt of Earth’s axis and its orbit around the sun. As Earth’s axis becomes less tilted, and its orbit more elliptical, it receives less solar radiation.

These “Milankovitch” cycles occur over thousands of years. Currently, Earth’s tilt is halfway between its maximum and minimum while its orbit is nearly circular.

In the absence of human activity, Earth may have gradually cooled in the coming centuries with phases corresponding to a decreasing tilt and an increasing orbital eccentricity.

However, fossil-fuel burning and other actions have raised CO2 levels to 420 parts per million—far above the 180-280 ppm seen during past ice ages. This extra CO2 has made it harder for heat to escape the atmosphere, overpowering the natural cooling trend.

Go to full rebuttal on Skeptical Science or to the fact brief on Gigafact

This fact brief is responsive to conversations such as this one.

Sources

NASA Milankovitch (Orbital) Cycles and Their Role in Earth’s Climate

Cornell University Understanding long-term climate and CO2 change

UC San Diego The Keeling Curve Hits 420 PPM

Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Are we heading toward another Little Ice Age?

NASA Global Temperature

Skeptical Science New Research for Week #51 2024

Posted on 19 December 2024 by Doug Bostrom, Marc Kodack

Open access notables

An intensification of surface Earth’s energy imbalance since the late 20th century, Li et al., Communications Earth & Environment:

Tracking the energy balance of the Earth system is a key method for studying the contribution of human activities to climate change. However, accurately estimating the surface energy balance has long been a challenge, primarily due to uncertainties that dwarf the energy flux changes induced and a lack of precise observational data at the surface. We have employed the Bayesian Model Averaging (BMA) method, integrating it with recent developments in surface solar radiation observational data, to refine the ensemble of CMIP6 model outputs. This has resulted in an enhanced estimation of Surface Earth System Energy Imbalance (EEI) changes since the late 19th century. Our findings show that CMIP6 model outputs, constrained by this observational data, reflect changes in energy imbalance consistent with observations in Ocean Heat Content (OHC), offering a narrower uncertainty range at the 95% confidence level than previous estimates. Observing the EEI series, dominated by changes due to external forcing, we note a relative stability (0.22 Wm−2) over the past half-century, but with a intensification (reaching 0.80 Wm−2) in the mid to late 1990s, indicating an escalation in the adverse impacts of global warming and climate change, which provides another independent confirmation of what recent studies have shown.

Fusion of Probabilistic Projections of Sea-Level Rise, Grandey et al., Earth's Future:

A probabilistic projection of sea-level rise uses a probability distribution to represent scientific uncertainty. However, alternative probabilistic projections of sea-level rise differ markedly, revealing ambiguity, which poses a challenge to scientific assessment and decision-making. To address the challenge of ambiguity, we propose a new approach to quantify a best estimate of the scientific uncertainty associated with sea-level rise. Our proposed fusion combines the complementary strengths of the ice sheet models and expert elicitations that were used in the Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Under a low-emissions scenario, the fusion's very likely range (5th–95th percentiles) of global mean sea-level rise is 0.3–1.0 m by 2100. Under a high-emissions scenario, the very likely range is 0.5–1.9 m. The 95th percentile projection of 1.9 m can inform a high-end storyline, supporting decision-making for activities with low uncertainty tolerance. By quantifying a best estimate of scientific uncertainty, the fusion caters to diverse users.

Earth's Climate History Explains Life's Temperature Optima, Schipper et al., Ecology and Evolution:

Why does the growth of most life forms exhibit a narrow range of optimal temperatures below 40°C? We hypothesize that the recently identified stable range of oceanic temperatures of ~5 to 37°C for more than two billion years of Earth history tightly constrained the evolution of prokaryotic thermal performance curves to optimal temperatures for growth to less than 40°C. We tested whether competitive mechanisms reproduced the observed upper limits of life's temperature optima using simple Lotka–Volterra models of interspecific competition between organisms with different temperature optima. Model results supported our proposition whereby organisms with temperature optima up to 37°C were most competitive. Model results were highly robust to a wide range of reasonable variations in temperature response curves of modeled species. We further propose that inheritance of prokaryotic genes and subsequent co-evolution with microbial partners may have resulted in eukaryotes also fixing their temperature optima within this narrow temperature range. We hope this hypothesis will motivate considerable discussion and future work to advance our understanding of the remarkable consistency of the temperature dependence of life.

Widespread outdoor exposure to uncompensable heat stress with warming, Fan & McColl, Communications Earth & Environment:

Previous studies projected an increasing risk of uncompensable heat stress indoors in a warming climate. However, little is known about the timing and extent of this risk for those engaged in essential outdoor activities, such as water collection and farming. Here, we employ a physically-based human energy balance model, which considers radiative, wind, and key physiological effects, to project global risk of uncompensable heat stress outdoors using bias-corrected climate model outputs. Focusing on farmers (approximately 850 million people), our model shows that an ensemble median 2.8% (15%) would be subject to several days of uncompensable heat stress yearly at 2 (4) °C of warming relative to preindustrial. Focusing on people who must walk outside to access drinking water (approximately 700 million people), 3.4% (23%) would be impacted at 2 (4) °C of warming. Outdoor work would need to be completed at night or in the early morning during these events.

["uncompensable" means physiologically intolerable, acutely dangerous, ultimately deadly]

Stabilising CO2 concentration as a channel for global disaster risk mitigation, Lu & Tambakis, Scientific Report:

We investigate the influence of anthropogenic CO2 concentration fluctuations on the likelihood of climate-related disasters. We calibrate annual incidence rates against global disasters and CO2 growth spanning from 1960 to 2022 based on a dynamic panel logit model. We also study the sensitivity of disaster incidence to stochastic carbon dynamics consistent with IPCC-projected climate outcomes for 2100. The key insight is that present and lagged CO2 growth contains valuable information about the likelihood of future disaster events. We further show that lowering carbon stock uncertainty by dampening the persistence or the variability of CO2 concentration has a first-order impact on mitigating expected disaster risk.

Fact-checking information from large language models can decrease headline discernment, DeVerna et al., Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences:

This study explores how large language models (LLMs) used for fact-checking affect the perception and dissemination of political news headlines. Despite the growing adoption of AI and tests of its ability to counter online misinformation, little is known about how people respond to LLM-driven fact-checking. This experiment reveals that even LLMs that accurately identify false headlines do not necessarily enhance users’ abilities to discern headline accuracy or promote accurate news sharing. LLM fact checks can actually reduce belief in true news wrongly labeled as false and increase belief in dubious headlines when the AI is unsure about an article’s veracity. These findings underscore the need for research on AI fact-checking’s unintended consequences, informing policies to enhance information integrity in the digital age.

Droughts in Wind and Solar Power: Assessing Climate Model Simulations for a Net-Zero Energy Future, Liu et al., Geophysical Research Letters:

Understanding and predicting “droughts” in wind and solar power availability can help the electric grid operator planning and operation toward deep renewable penetration. We assess climate models' ability to simulate these droughts at different horizontal resolutions, ∼100 and ∼25 km, over Western North America and Texas. We find that these power droughts are associated with the high/low pressure systems. The simulated wind and solar power variabilities and their corresponding droughts during historical periods are more sensitive to the model bias than to the model resolution. Future climate simulations reveal varied future change of these droughts across different regions. Although model resolution does not affect the simulation of historical droughts, it does impact the simulated future changes. This suggests that regional response to future warming can vary considerably in high- and low-resolution models. These insights have important implications for adapting power system planning and operations to the changing climate.

From this week's government/NGO section:

How global warming beliefs differ by education levels in India, Morris et al., Yale Program on Climate Change Communication

Given India’s diverse population, it is likely that global warming beliefs vary across different subgroups of the population. Given the large differences in levels of educational attainment in India, education might be an especially important factor in Indians’ global warming beliefs and attitudes. Further, understanding the role of education in public responses to climate change can help inform the design of communication strategies for these different subgroups. There were large differences in global warming awareness. For people who are not literate, 56% say they have never heard of global warming while, for people with a college degree or higher, only 7% say the same. Global warming awareness increases as educational level increases.

U.S. Climate Pathways for 2035 with Strong Non-Federal Leadership, Zhao et al., Center for Global Sustainability, University of Maryland

The authors assess U.S. climate pathways for 2035 across a range of federal climate ambitions with continued and enhanced non-federal climate action. The authors find that in the event of the reversal of strong federal climate action, enhanced non-federal action alone could still significantly bolster the transition to clean energy. With actions including the widespread adoption of renewable and clean electricity targets, California’s EV sales targets, vehicle miles traveled reduction policies, building efficiency, and electrification standards, industry carbon capture and sequestration targets, oil and gas methane intensity standards, and increased waste diversion efforts, the United States could achieve 54-62% emissions reductions by 2035, even in the context of federal inactions or rollbacks.

Voters Support Phasing Out Fossil Fuel Extraction, Caggiano et al., Climate and Community Institute

While the United States has made progress towards a buildout of clean and renewable energy, there has been very little serious discussion of curtailing fossil fuel extraction. Though many politicians believe that halting existing or new fossil fuel production is politically unpopular, there is surprisingly limited data to back this claim. To better understand how the general public views policies aimed at phasing out fossil fuel production, we conducted a nationally representative survey. Overall, the results demonstrate widespread support for policies to curtail the extraction of fossil fuels.

135 articles in 62 journals by 878 contributing authors

Physical science of climate change, effects

Acceleration of Warming, Deoxygenation, and Acidification in the Arabian Gulf Driven by Weakening of Summer Winds, Lachkar et al., Geophysical Research Letters Open Access 10.1029/2024gl109898

Basic Physics Predicts Stronger High Cloud Radiative Heating With Warming, Gasparini et al., Geophysical Research Letters Open Access pdf 10.1029/2024gl111228

Stop emissions, stop warming: A climate reality check

Posted on 18 December 2024 by Guest Author

This is a re-post from The Climate Brink by Andrew Dessler

One of the most important concepts in climate science is the idea of committed warming — how much future warming is coming from carbon dioxide that we’ve already emitted.

Understanding the extent of committed warming is vital because it informs our current climate situation. If there is a significant amount of committed warming already “locked in,” then we have much less ability to avoid the levels of warming that policymakers judge as dangerous.

In a previous post about what made me optimistic about the climate problem, I wrote:

When humans stop emitting greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, the climate will stop warming.

I received emails and comments from people who found that difficult to believe, so I thought I’d write a post about why this is true and shed light on the reasons behind the controversy surrounding it.

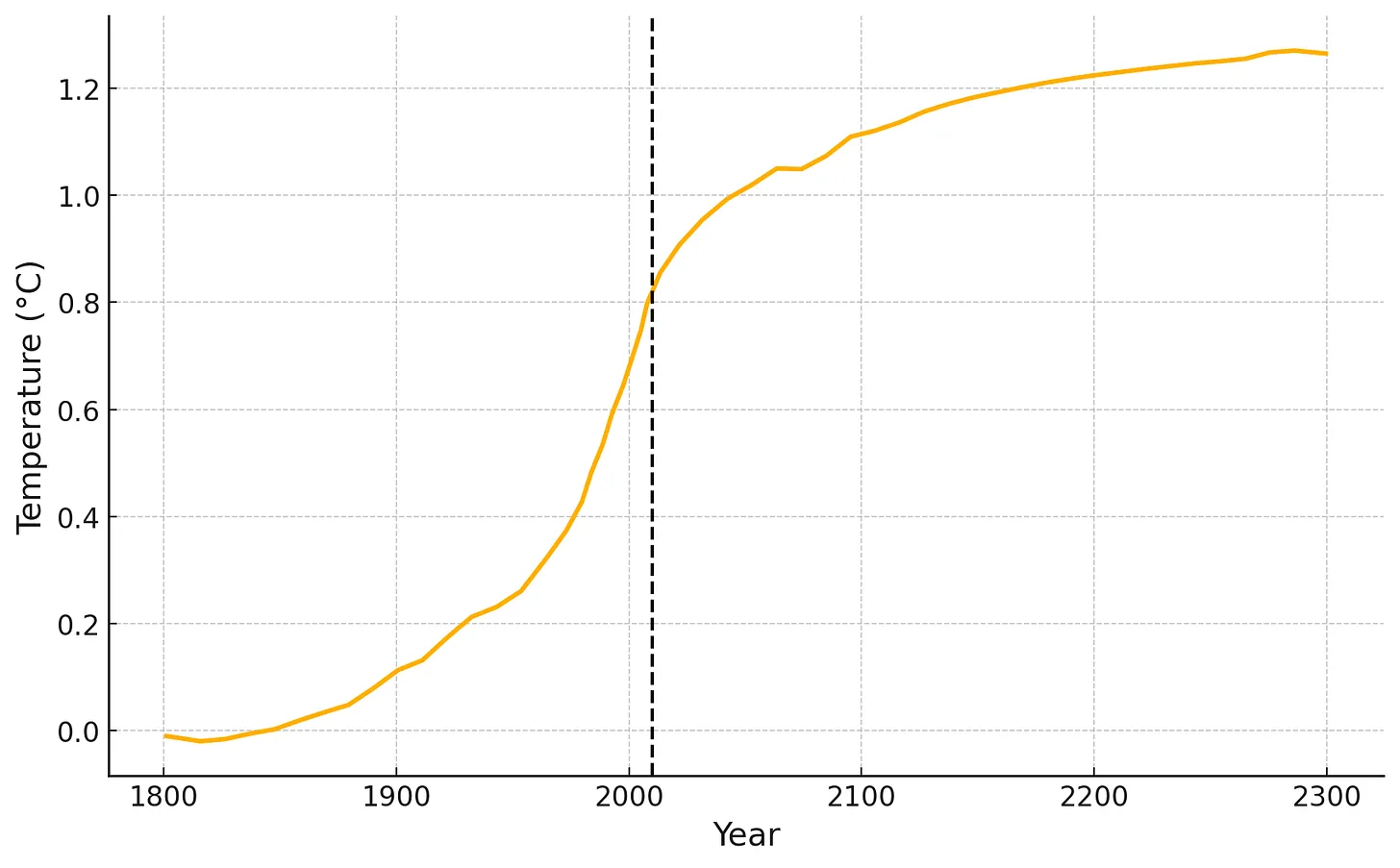

the 2000s

To understand why people are so confused about this, let’s step back to the 2000s. In the IPCC’s fourth assessment report (published in 2007), committed warming was defined to be:

If the concentrations of greenhouse gases and aerosols were held fixed after a period of change, the climate system would continue to respond due to the thermal inertia of the oceans and ice sheets and their long time scales for adjustment. ‘Committed warming’ is defined here as the further change in global mean temperature after atmospheric composition, and hence radiative forcing, is held constant. (from box TS.9)

Consider this simple example: humans emit CO2 until the year 2010, when the atmospheric concentration of CO2 reaches 400 ppm. After that point, the concentration of CO2 is held fixed at 400 ppm in perpetuity, as are all other components of the atmosphere (methane, aerosols, etc.).

In this scenario, maintaining a fixed atmospheric composition is analogous to setting a thermostat at a constant set point for the Earth's climate system. This is the resulting trajectory:

As you can see, the climate continues to warm well after concentrations are fixed (the vertical dashed line). The reason is the immense thermal inertia of the ocean. In much the same way that it takes a very long time for a hot tub filled with cold water to warm after you set the heater, the oceans will take a very very long time to fully warm to reach equilibrium with the fixed atmospheric composition.

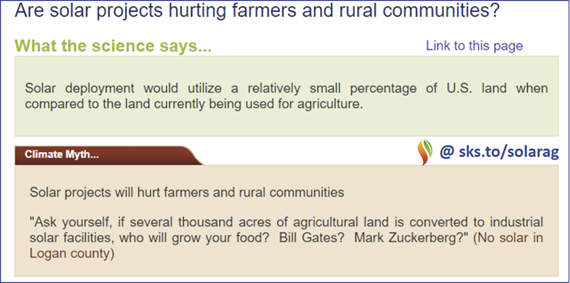

Sabin 33 #7 - Are solar projects hurting farmers and rural communities?

Posted on 17 December 2024 by BaerbelW

On November 1, 2024 we announced the publication of 33 rebuttals based on the report "Rebutting 33 False Claims About Solar, Wind, and Electric Vehicles" written by Matthew Eisenson, Jacob Elkin, Andy Fitch, Matthew Ard, Kaya Sittinger & Samuel Lavine and published by the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia Law School in 2024. Below is the blog post version of rebuttal #7 based on Sabin's report.

Ambitious solar deployment would utilize a relatively small percentage of U.S. land when compared to the land currently being used for agriculture. The Department of Energy estimated that total U.S. solar development would take up roughly 10.3 million acres in a scenario in which cumulative solar deployment reaches 1,050–1,570 GW by 2050, the highest land-use scenario that DOE assessed in its 2021 Solar Futures Study1. If all 10.3 million acres of solar farms were sited on farmland, they would occupy only 1.15% of the 895,300,000 acres of U.S. farmland as of 20212. However, many of these projects will not be located on farmland.

Furthermore, solar arrays can be designed to allow, and even enhance, continued agricultural production on site. This practice, known as agrivoltaics, provides numerous benefits to farmers and rural communities, especially in hot or dry climates3. Agrivoltaics allow farmers to grow crops and even to graze livestock such as sheep beneath or between rows of solar panels4 (also Adeh et al. 2019). When mounted above crops and vegetation, solar panels can provide beneficial shade during the day (Williams et al. 2023). Multiple studies have shown that these conditions can enhance a farm’s productivity and efficiency (Aroca-Delgado et al. 2018). One study found, for example, that "lettuces can maintain relatively high yields under PV" because of their capacity to calibrate "leaf area to light availability" (Marrou et al. 2013). Extra shading from solar panels also reduces evaporation, thereby reducing water usage for crops by around 14-29%, depending on the level of shade (Dinesh & Pearce 2016). Reduced evaporation from solar installations can likewise mitigate soil erosion. Solar farms can also create refuge habitats for endangered pollinator species, further boosting crop yields while supporting native wild species5. Overall, agrivoltaics can increase the economic value of the average farm by over 30%, while increasing annual income by about 8%. Farmers in other countries have begun implementing agrivoltaic systems (Tajima & Iida 2021). As of March 2019, Japan had 1,992 agrivoltaic farms, growing over 120 different crops while simultaneously generating 500,000 to 600,000 MWh of energy6.

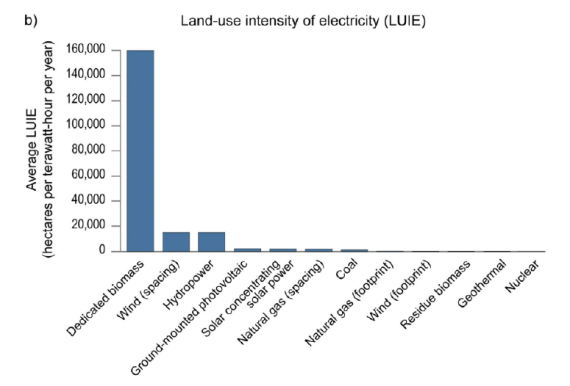

Furthermore, the argument that solar development will imperil the food supply is belied by the fact that tens of millions of acres of farmland are currently being used to grow crops for other purposes, such as the production of corn ethanol. Currently, roughly 90 million acres of agricultural land in the United States is dedicated to corn, with nearly 45% of that corn being used for ethanol production7. Solar energy could provide a significantly more efficient use of the same land. Corn-derived ethanol used to power internal combustion engines has been calculated to require between 63 and 197 times more land than solar PV powering electric vehicles to achieve the same number of transportation miles8. If converted to electricity to power electric vehicles, ethanol would still need roughly 32 times more land than solar PV to achieve the same number of transportation miles. And even when accounting for other energy by-products of ethanol production, solar PV produces between 14 and 17 times more gross energy per acre than corn. The figure below contrasts the land use requirements of solar PV with dedicated biomass and other energy sources. Whereas dedicated biomass consumes an average of 160,000 hectares of land per terawatt-hour per year, ground-mounted solar PV consumes an average of 2,100 (Lovering et al. 2022).

Figure 4: Average land-use intensity of electricity, measured in hectares per terawatt-hour per year. Source: U.S. Global Change Research Program (visualizing data from Jessica Lovering et al. 2022).

Finally, while solar installations, like any infrastructure projects, will inevitably have some adverse impacts, the failure to build the infrastructure necessary to avoid climate change poses a far more severe threat to agricultural production. Climate change already harms food production across the country and globe through extreme weather events, weather instability, and water scarcity9. The most recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report forecasts that climate change will cause up to 80 million additional people to be at risk of hunger by 205010. A 2019 IPCC report forecasted up to 29% price increases for cereal grains by 2050 due to climate change11. These price increases would strain consumers globally, while also producing uneven regional effects. Moreover, while higher carbon dioxide levels may initially increase yield for certain crops at lower temperature increases, these crops will likely provide lower nutritional quality. For example, wheat grown at 546–586 parts per million (ppm) CO2 has a 5.9–12.7% lower concentration of protein, 3.7–6.5% lower concentration of zinc, and 5.2–7.5% lower concentration of iron. Distributions of pests and diseases will also change, harming agricultural production in many regions. Such impacts will only intensify for as long as we continue to burn fossil fuels12.

How much should you worry about a collapse of the Atlantic conveyor belt?

Posted on 16 December 2024 by Guest Author

This is a re-post from Yale Climate Connections by Bob Henson

In this aerial view, fingers of meltwater flow from the melting Isunnguata Sermia glacier descending from the Greenland Ice Sheet on July 11, 2024, near Kangerlussuaq, Greenland. According to the Programme for Monitoring of the Greenland Ice Sheet (PROMICE), the Greenland Ice Sheet has been losing mass continuously since 1996, with an accumulated loss since 1986 approaching 6,000 metric gigatons, or 6 trillion tons. Meltwater pouring from the Arctic into the far North Atlantic in massive amounts seems to be capable of triggering collapse of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation. (Photo by Sean Gallup/Getty Images)

In this aerial view, fingers of meltwater flow from the melting Isunnguata Sermia glacier descending from the Greenland Ice Sheet on July 11, 2024, near Kangerlussuaq, Greenland. According to the Programme for Monitoring of the Greenland Ice Sheet (PROMICE), the Greenland Ice Sheet has been losing mass continuously since 1996, with an accumulated loss since 1986 approaching 6,000 metric gigatons, or 6 trillion tons. Meltwater pouring from the Arctic into the far North Atlantic in massive amounts seems to be capable of triggering collapse of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation. (Photo by Sean Gallup/Getty Images)

Several high-profile research papers have brought renewed attention to the potential collapse of a crucial system of ocean currents known as the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, or AMOC, as we discussed in part one of this two-part post. Huge uncertainties in both the timing and details of potential impacts of such a collapse remain. Even so, scientists warned in a recent open letter (see below) that “such an ocean circulation change would have devastating and irreversible impacts.”

The AMOC is a vast oceanic loop that carries warm water northward through the uppermost Atlantic toward Iceland and Greenland, where it cools and descends before returning southward. The Gulf Stream, which carries warm water from the tropics toward Europe, is an important section of this loop. Studies of ancient climates reveal that in the distant climate past, AMOC has gone through cycles of collapse that lasted hundreds of years. As we saw in part one, these “off” cycles of the AMOC brought massive environmental changes that would lead to tremendous havoc should they descend on today’s complex, interconnected world.

In part one, we looked at observations from the North Atlantic that suggest a gradual weakening in AMOC strength over the last few decades, but only a marginally significant drop over the past 40 years of AMOC monitoring, including the largest near-surface component, the Gulf Stream.

By no means does this rule out the possibility of a forthcoming AMOC collapse. New research is leading to startlingly specific time frames for when the AMOC might collapse. These studies aren’t without controversy, as we’ll see below. But collectively, they’ve raised the profile of AMOC – and also raised fears that the initial impacts of AMOC collapse could manifest within the lifetimes of many of us.

Stefan Rahmstorf at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research is an eminent researcher who’s studied AMOC and its various modes for more than 30 years. In October 2024, discussing the specter of AMOC collapse, Rahmstorf warned:

Even with a medium likelihood of occurrence, given that the outcome would be catastrophic and impacting the entire world for centuries to come, we believe more needs to be done to minimize this risk.

2024 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming News Roundup #50

Posted on 15 December 2024 by BaerbelW, Doug Bostrom, John Hartz

Listing by Category

Like last week's summary this one contains the list of articles twice: based on categories and based on publication date. Please feel free to let us know in the comments - if you haven't already - which one you prefer. Checking if we assigned the (most) relevant category is also appreciated. Thanks for your help with this!

Climate change impacts

- New York Isn`t Ready to Fight More Wildfires New York could see more frequent and destructive blazes, but the state doesn’t have enough forest rangers and firefighters to respond to the growing threat. by Nathan Porceng, Inside Climate News, Dec 08, 2024

- Climate crisis deepens with 2024 `certain` to be hottest year on record Average global temperature in November was 1.62C above preindustrial levels, bringing average for the year to 1.60C by Damian Carrington, The Guardian, Dec 09, 2024

- This county has an ambitious climate agenda. That`s not easy in Florida. Alachua County is preparing for a more dangerous future, even if the state government won't say "climate." by Sachi Kitajima Mulkey, Grist, Dec 09, 2024

- Autumn 2024 was the warmest in U.S. history, NOAA says "It may also end up being the nation’s warmest year on record.." by Bob Henson, Eye on the Storm, Yale Climate Connections, Dec 9, 2024

- The town that fears losing its high street to climate change - podcast Flooding in Tenbury Wells used to be a once in a generation event, now its happening increasingly frequently. by Presented by Hannah Moore with Jessica Murrayand Helena Horton; produced by Eli Block, Rachel Keenan and Rudi Zygadlo; executive producer Homa Khaleeli, The Guardian, Dec 11, 2024

- Extreme weather disrupts education worldwide Between January 2022 and June 2024, over 400 million students were affected. by YCC Team, Yale Climate Connections, Dec 11, 2024

- November 2024: Earth`s 2nd-warmest November on record The year 2024 is virtually certain to be Earth’s second consecutive warmest year on record. by Jeff Masters, Yale Climate Connections, Dec 12, 2024

- The Night Shift "With extreme heat making it perilous to work during the day, farmers and fisherfolk worldwide are adopting overnight hours. That comes with new dangers." by Ayurella Horn-Muller, Grist, Dec 11, 2024

Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation

- This startup is using AI to ‘supercharge’ crop breeding. It could help protect farmers from the climate crisis by Jack Bantock & Gisella Deputato, Climate, CNN, Dec 2, 2024

- Sabin 33 #6 - Are solar projects harming biodiversity? by Bärbel Winkler, Skeptical Science, Dec 10, 2024

- Scientists advise EU to halt solar geoengineering There’s ‘insufficient scientific evidence’ backing efforts to artificially cool down the planet, according to the European Commission’s scientific advisers. by Justine Calma, The Verge - Science Posts, Dec 09, 2024

Skeptical Science New Research for Week #50 2024

Posted on 12 December 2024 by Doug Bostrom, Marc Kodack

Open access notables:

Climate risk assessments must account for a wide range of possible futures, so scientists often use simulations made by numerous global climate models to explore potential changes in regional climates and their impacts. Some of the latest-generation models have high effective climate sensitivities (EffCS). It has been argued these “hot” models are unrealistic and should therefore be excluded from analyses of climate change impacts. Whether this would improve regional impact assessments, or make them worse, is unclear. Here we show there is no universal relationship between EffCS and projected changes in a number of important climatic drivers of regional impacts. Analyzing heavy rainfall events, meteorological drought, and fire weather in different regions, we find little or no significant correlation with EffCS for most regions and climatic drivers. Even when a correlation is found, internal variability and processes unrelated to EffCS have similar effects on projected changes in the climatic drivers as EffCS. Model selection based solely on EffCS appears to be unjustified and may neglect realistic impacts, leading to an underestimation of climate risks.

Assessing compliance with the human-induced warming goal in the Paris Agreement requires transparent, robust and timely metrics. Linearity between increases in atmospheric CO2 and temperature offers a framework that appears to satisfy these criteria, producing human-induced warming estimates that are at least 30% more certain than alternative methods. Here, for 2023, we estimate humans have caused a global increase of 1.49 ± 0.11 °C relative to a pre-1700 baseline.

Climate change is expected to cause irreversible changes to biodiversity, but predicting those risks remains uncertain. I synthesized 485 studies and more than 5 million projections to produce a quantitative global assessment of climate change extinctions. With increased certainty, this meta-analysis suggests that extinctions will accelerate rapidly if global temperatures exceed 1.5°C. The highest-emission scenario would threaten approximately one-third of species, globally. Amphibians; species from mountain, island, and freshwater ecosystems; and species inhabiting South America, Australia, and New Zealand face the greatest threats. In line with predictions, climate change has contributed to an increasing proportion of observed global extinctions since 1970. Besides limiting greenhouse gases, pinpointing which species to protect first will be critical for preserving biodiversity until anthropogenic climate change is halted and reversed.

A Trojan horse for climate policy: Assessing carbon lock-ins through the Carbon Capture and Storage-Hydrogen-Nexus in Europe, Faber et al., Energy Research & Social Science:

The global energy landscape is entrenched in fossil fuels, shaping modern life profoundly. Germany, a prominent example, grapples with transitioning from its fossil-fuelled infrastructure despite governmental support for decarbonization. Carbon capture and storage (CCS) and hydrogen appear as crucial tools in this transition. A recent partnership between Germany and Norway seeks to leverage Norway's CCS and hydrogen expertise to aid Germany's decarbonization efforts. However, CCS faces criticism for potential mitigation deterrence and carbon lock-ins, perpetuating fossil fuel reliance. This study critically analyses the Norwegian-German CCS-Hydrogen-Nexus, focusing on potential carbon lock-ins. By examining specific projects, institutional frameworks, and industry involvement, we aim to elucidate the partnership's implications for carbon lock-ins. This critical case holds significance for Europe's largest economy and offers insights applicable to CCS technology globally. We find that the current setup perpetuates existing carbon lock-ins both in Germany and Norway. Central problems are the interchangeability of blue and green hydrogen, asset specificity of pipeline and pumping infrastructure and the central role which actors from the fossil fuel industry play in the rollout of the CCS-Hydrogen-Nexus. Our concern is that this approach might entrench the energy system in a socially unjust state. EU policy on blue hydrogen emerged as a factor that helps to avoid carbon lock-ins.

Heat disproportionately kills young people: Evidence from wet-bulb temperature in Mexico, Wilson et al., Science Advances:

Recent studies project that temperature-related mortality will be the largest source of damage from climate change, with particular concern for the elderly whom it is believed bear the largest heat-related mortality risk. We study heat and mortality in Mexico, a country that exhibits a unique combination of universal mortality microdata and among the most extreme levels of humid heat. Combining detailed measurements of wet-bulb temperature with age-specific mortality data, we find that younger people are particularly vulnerable to heat: People under 35 years old account for 75% of recent heat-related deaths and 87% of heat-related lost life years, while those 50 and older account for 96% of cold-related deaths and 80% of cold-related lost life years. We develop high-resolution projections of humid heat and associated mortality and find that under the end-of-century SSP 3–7.0 emissions scenario, temperature-related deaths shift from older to younger people. Deaths among under-35-year-olds increase 32% while decreasing by 33% among other age groups.

Drivers of global tourism carbon emissions, Sun et al., Nature Communications:

Tourism has a critical role to play in global carbon emissions pathway. This study estimates the global tourism carbon footprint and identifies the key drivers using environmentally extended input-output modelling. The results indicate that global tourism emissions grew 3.5% p.a. between 2009-2019, double that of the worldwide economy, reaching 5.2 Gt CO2-e or 8.8% of total global GHG emissions in 2019. The primary drivers of emissions growth are slow technology efficiency gains (0.3% p.a.) combined with sustained high growth in tourism demand (3.8% p.a. in constant 2009 prices). Tourism emissions are associated with alarming distributional inequalities. Under both destination- and resident-based accounting, the twenty highest-emitting countries contribute three-quarters of the global footprint. The disparity in per-capita tourism emissions between high- and low-income nations now exceeds two orders of magnitude. National tourism decarbonisation strategies will require demand volume thresholds to be defined to align global tourism with the Paris Agreement.

From this week's government/NGO section:

How Americans View Climate Change and Policies to Address the Issue, Brian Kennedy and Alec Tyson, Pew Research Center

Americans are split over the economic impact of climate policies. Large businesses and corporations are seen as doing too little on climate change. There is broad support for policies to address climate change. There is widespread frustration with political disagreement over climate change. 64% say climate change currently affects their local community either a great deal or some. Relatively few expect to make major sacrifices in their lifetime due to climate change

Transboundary adaption to climate change: governing flows of water, energy, food and people, Nicholas Simpson and Portia Williams, Overseas Development Institute

Climate change alters transboundary flows that are essential for people and nature, including flows of water, people, energy, and food. Transboundary adaptation can reduce risks by focusing interventions at the origin or source of the climate change impact, along transmission channels, and in the destination country or region. Anticipating, planning for, and managing flows across geographic and sectoral boundaries builds resilience across interconnected systems and populations. Transboundary adaptation is strengthened and more effective when using a nexus approach, which considers how interconnected flows such as hydropower changes affect irrigation and/or energy needs. Greater recognition of governance of transboundary flows within adaptation planning can better identify and manage systemic vulnerabilities that escalate climate change risk. Strengthening governance frameworks to improve cross-border cooperation must be done in conjunction with addressing critical dimensions of vulnerability and promoting the integrated management of shared resources.

148 articles in 52 journals by 811 contributing authors

Physical science of climate change, effects

A pause in the weakening of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation since the early 2010s, Lee et al., Nature Communications Open Access 10.1038/s41467-024-54903-w

Estimated human-induced warming from a linear temperature and atmospheric CO2 relationship, Jarvis & Forster, Nature Geoscience Open Access 10.1038/s41561-024-01580-5

Irreversible changes in the sea surface temperature threshold for tropical convection to CO2 forcing, Park et al., Communications Earth & Environment Open Access 10.1038/s43247-024-01751-7

How unusual is current post-El Niño warmth?

Posted on 11 December 2024 by Zeke Hausfather

This is a re-post from The Climate Brink

As I noted a few months back, despite the end of El Niño conditions in May, global temperatures have remained worryingly elevated. This raises the question of whether this reflects unusual El Niño behavior, or a more persistent change in the underlying climate forcings or feedbacks.

At the time I did a fairly basic analysis comparing the current 2023/2024 El Niño event to the two other recent strong El Niño events – those in 1997/1998 and 2015/2016. However, an “N” of two does not tell us all that much, and the approach was overly simplified in not actually accounting for differing El Niño timing or accurately normalizing for the warming between El Niño events.

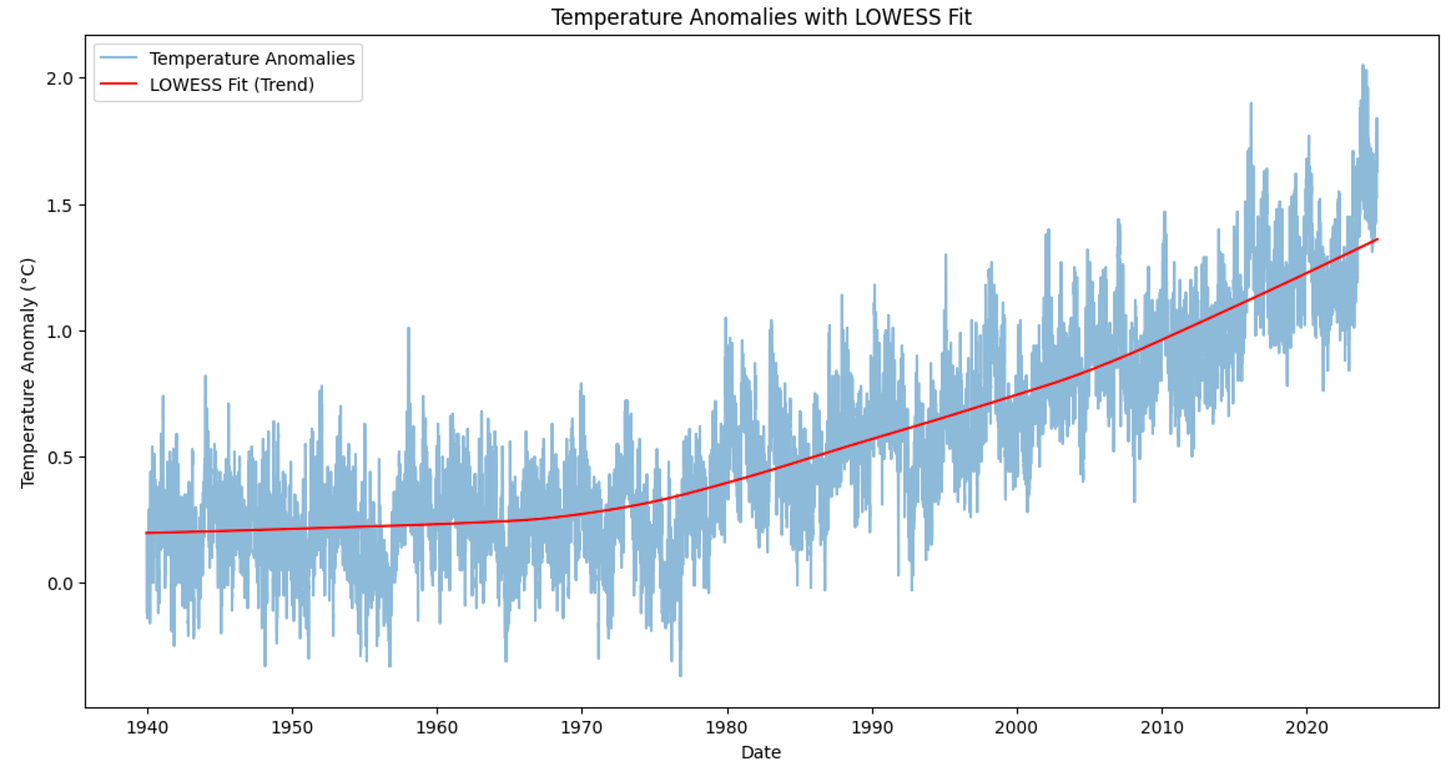

So I decided a more thorough analysis was in order, looking at the evolution of daily temperatures across all El Niño events using the ERA5 reanalysis dataset. Given that this dataset covers the period from 1940 to present, it gives us a six strong El Niño events (Niño 3.4 region > 1.8C) and four more moderate El Niño events (Niño 3.4 region > 1.5C and < 1.8C) to compare with what is happening this year.

It turns out that even looking at the longer record, the evolution of global surface temperatures both before and after the El Niño is unprecedented: temperatures rose earlier than we’ve seen before, and temperatures have remained at elevated levels for a longer period of time.

Isolating El Niño’s effect on warming

To isolate the effect of El Niño events on surface temperatures we first need to remove an important confounding component: the effect of human emissions of CO2 and other greenhouse gases (and aerosols) on global mean surface temperatures.

The figure below shows the approach I used, which involved fitting a locally linear regression (LOWESS) to ERA5 daily temperature anomalies between 1940 and present. This approach is more flexible than a simple linear fit, as it allows for changes in the rate of warming over the course of the record: slow warming pre-1970, faster warming between 1970 and 2005, and a modest acceleration in the rate of warming after 2005.

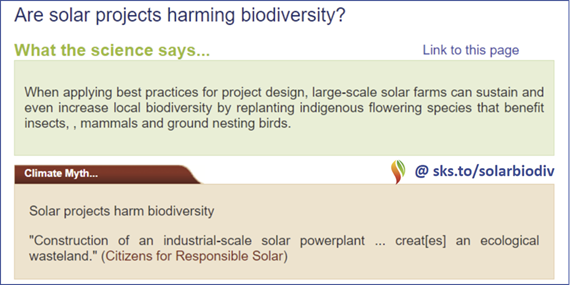

Sabin 33 #6 - Are solar projects harming biodiversity?

Posted on 10 December 2024 by BaerbelW

On November 1, 2024 we announced the publication of 33 rebuttals based on the report "Rebutting 33 False Claims About Solar, Wind, and Electric Vehicles" written by Matthew Eisenson, Jacob Elkin, Andy Fitch, Matthew Ard, Kaya Sittinger & Samuel Lavine and published by the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia Law School in 2024. Below is the blog post version of rebuttal #6 based on Sabin's report.

The impact of solar development on biodiversity depends on-site specific conditions, such as the local ecosystem, the existing land use, the density of development, and the management practices employed at the site. When applying best practices for project design, including by incorporating pollinator habitat and minimizing soil disturbance, large-scale solar farms on previously developed land, including farmland, can sustain and even increase local biodiversity (Sinha et al. 2018). While developing solar projects on previously undeveloped land may contribute to habitat loss and degradation, as well as negative impacts to local biodiversity, these impacts can be mitigated by avoiding bulldozing and by creating wildlife corridors and habitat patches inside the footprint of the facility where soil and vegetation is not disturbed (Grodsky et al. 2021, Suuronen et al. 2017, Sawyer et al. 2022).

Microclimates within solar farms can enhance botanical diversity, which, in turn can enhance the diversity of the site’s invertebrate and bird populations. In addition, the shade under solar panels can offer critical habitat for a wide range of species, including endangered species1 (also Graham et al. 2021). Shady patches likewise prevent soil moisture loss, boosting plant growth and diversity, particularly in areas impacted by climate extremes (Barron-Gafford et al. 2019).

Proactive measures taken before and after a solar farm’s construction can further enhance biodiversity. Prior to installation, developers can mitigate adverse impacts by examining native species’ feeding, mating and migratory patterns and ensuring that solar projects are not sited in sensitive locations or constructed at sensitive times2. For example, developers can schedule construction to coincide with indigenous reptiles’ and amphibians’ hibernation periods, while avoiding breeding periods.

Additionally, developers can invest in habitat restoration once solar projects have been installed, such as by replanting indigenous flowering species that provide nectar to insects, which also benefits mammals and ground nesting birds. A recent study on the impact of newly-established insect habitat on solar farms in agricultural landscapes found increases in floral abundance, flowering plant species richness, insect group diversity, native bee abundance, and total insect abundance (Walston et al. 2023).

Pollinators play a crucial role in U.S. farming, with more than one third of crop production reliant on pollinators3. Bee populations alone contribute an estimated $20 billion annually to U.S. agriculture production and up to $217 billion worldwide. Recognizing these important contributions, the U.S. Department of Energy’s Solar Technologies Office is currently funding or tracking numerous studies that seek to maximize solar farms’ positive impacts on pollinator-friendly plants4.

As renewables rise, the world may be nearing a climate turning point

Posted on 9 December 2024 by dana1981

This is a re-post from Yale Climate Connections

Climate pollution caused by burning fossil fuels hit a record 37.4 billion metric tons in 2024, marking a 0.8% rise from the previous year – and dashing hopes that a peak in global emissions might occur this year.

That’s according to the latest annual Global Carbon Budget, which underscores a deeper challenge: the world’s ongoing reliance on coal, oil, and gas, which continues to drive emissions and disrupt the climate. The report, organized by a global consortium of scientists centered at the University of Exeter, paints a complex picture of global energy trends, with troubling increases in some areas and signs of progress in others.

Emissions from most wealthy countries fell this year, though by relatively small amounts in many cases. Meanwhile, climate pollution from most developing economies rose, driven by economic growth and a rising demand for energy. Global consumption of coal, oil, and gas all increased, though coal and oil saw less than 1% growth.

While global emissions have yet to reach a clear “peak” – the point at which carbon pollution stops rising and eventually shifts to a consistent decline – there are signs that this turning point could be on the horizon. The rapid deployment of clean technologies like solar panels and electric vehicles (EVs) may help accelerate this shift, although much faster progress will be needed to avoid the worst impacts of climate change.

These global trends have urgent implications for our climate, economies, and ecosystems. To understand what’s behind this year’s record highs and what they signal for the future, let’s explore the key factors shaping climate pollution today.

2024 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming News Roundup #49

Posted on 8 December 2024 by BaerbelW, Doug Bostrom, John Hartz

Alternative listing prototype

Instead of a "Story of the Week" we added a listing by assigned category, so this installment will have the same list of articles twice, first by category and then by publication date. Please let us know in the comments which format you prefer, if the manually assigned categories actually fit the articles and if additional categories might make sense without getting too fine grained. To keep things simple, an article can only be assigned to one category.

Climate change impacts

- Doomsday Glacier collapse! Time for MORE human intervention?? by Dave Borlace, "Just have a Think" on Youtube, Dec 1, 2024

- An Arctic Hamlet is Sinking Into the Thawing Permafrost Canada is losing its permafrost to climate change. The Indigenous residents of Tuktoyaktuk know they’ll have to move but don’t agree on when. by Norimitsu Onishi and Renaud Philippe, NYT > Climate and Environment, Dec 02, 2024

- Climate change and insurance: a growing fustercluck In this podcast episode, David Roberts talks with Kate Gordon, CEO of California Forward, about how climate change is breaking the insurance industry. by David Roberts, Volts, Dec 04, 2024

- How climate risks are driving up insurance premiums around the US - visualized ‘Tight correlation’ between premium rises and counties deemed most at risk from climate crisis, experts say by Oliver Milman with graphics by Andrew Witherspoon, The Guardian, Dec 05, 2024

- Younger people at greater risk of heat-related deaths this century - study New research estimates a 32% increase in deaths of people under 35 if greenhouse gases not radically cut. by Oliver Milman, The Guardian, Dec 06, 2024

- Traditional Foods, and the Threats They Face, Take Center Stage at Navajo Summit Climate change is leading to a decline of many wild and farmed ingredients in traditional Diné staples, but presenters at the Food Gathering Summit hope that passing on recipes and legacies can help them persist. by Noel Lyn Smith, Inside Climate News, Dec 07, 2024

Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation

- Guest post: The conflicting practices in using land to tackle climate change Removing CO2 from the atmosphere using land-based mitigation strategies is central to nearly every country’s net-zero target. by Guest author Dr Evelyn Beaury,, Carbon Brief, Dec 05, 2024

Climate law and justice

- Top UN court to begin hearings on landmark climate change case ICJ to hear submissions from more than 100 groups in Pacific-led campaign to provide an advisory opinion on states’ obligations for climate harm by Rebecca Bush and Bethanie Harriman, The Guardian, Dec 02, 2024

- Australia accused of undermining landmark climate change case brought by Pacific nations in international court Vanuatu leads the charge of several nations arguing developed nations have a legal responsibility beyond non-binding promises by Adam Morton and Australian Associated Press, The Guardian, Dec 03, 2024

Interview with John Cook about misinformation and artificial intelligence

Posted on 6 December 2024 by John Cook, BaerbelW

In March, John Cook met with Adam Ford from Science, Technology & the Future to talk about his work researching misinformation and how to counter it. The interview - published on October 10 - explored the complex and evolving landscape of climate misinformation, covering a range of topics including the different types of misinformation, the role of social media and AI in spreading and combating it, the psychological barriers that prevent people from accepting climate science, and the importance of communicating effectively about climate change. Key takeaways include:

- The nature of climate misinformation: Misinformation takes many forms, including outright denial of climate science, attacks on climate scientists and solutions, and promotion of conspiracy theories. It is often emotionally driven and tailored to specific audiences.

- The role of social media and AI: Social media has amplified the spread of misinformation, and AI can be used to both generate and combat it. The development of sophisticated, personalized misinformation is a concerning and challenging trend.

- Psychological barriers to accepting climate science: These barriers include psychological distance and political ideology. Overcoming these barriers requires effective communication that address the underlying concerns and motivations of different audiences.

- The importance of human oversight: While AI is a powerful tool, human judgment is still crucial for accurately identifying and countering misinformation. Hybrid approaches that combine AI with human expertise are likely to be the most effective.

- The need for hope and efficacy: Communicating about climate change shouldn't just focus on the negative impacts. A message of hope and efficacy is needed to inspire action and avoid paralyzing people with fear.

The interview highlights the crucial role of ongoing research, education, and collaboration in addressing climate misinformation. It also emphasizes the importance of individual action, encouraging people to engage in conversations, connect with others, and use their unique skills and passions to contribute to the fight against climate change.

Skeptical Science New Research for Week #49 2024

Posted on 5 December 2024 by Doug Bostrom, Marc Kodack

Open access notables

Global emergence of regional heatwave hotspots outpaces climate model simulations, Kornhuber et al., Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences:

Multiple recent record-shattering weather events raise questions about the adequacy of climate models to effectively predict and prepare for unprecedented climate impacts on human life, infrastructure, and ecosystems. Here, we show that extreme heat in several regions globally is increasing significantly and faster in magnitude than what state-of-the-art climate models have predicted under present warming even after accounting for their regional summer background warming. Across all global land area, models underestimate positive trends exceeding 0.5 °C per decade in widening of the upper tail of extreme surface temperature distributions by a factor of four compared to reanalysis data and exhibit a lower fraction of significantly increasing trends overall. To a lesser degree, models also underestimate observed strong trends of contraction of the upper tails in some areas, while moderate trends are well reproduced in a global perspective. Our results highlight the need to better understand and model the drivers of extreme heat and to rapidly mitigate greenhouse gas emissions to avoid further harm from unexpected weather events.

The first ice-free day in the Arctic Ocean could occur before 2030, Heuzé & Jahn Jahn, Nature Communications:

Projections of a sea ice-free Arctic have so far focused on monthly-mean ice-free conditions. We here provide the first projections of when we could see the first ice-free day in the Arctic Ocean, using daily output from multiple CMIP6 models. We find that there is a large range of the projected first ice-free day, from 3 years compared to a 2023-equivalent model state to no ice-free day before the end of the simulations in 2100, depending on the model and forcing scenario used. Using a storyline approach, we then focus on the nine simulations where the first ice-free day occurs within 3–6 years, i.e. potentially before 2030, to understand what could cause such an unlikely but high-impact transition to the first ice-free day. We find that these early ice-free days all occur during a rapid ice loss event and are associated with strong winter and spring warming.

Global lake phytoplankton proliferation intensifies climate warming, Shi et al., Nature Communications:

In lakes, phytoplankton sequester atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) and store it in the form of biomass organic carbon (OC); however, only a small fraction of the OC remains buried, while the remaining part is recycled to the atmosphere as CO2 and methane (CH4). This has the potential effect of adding CO2-equivalents (CO2-eq) to the atmosphere and producing a warming effect due to the higher radiative forcing of CH4 relative to CO2. Here we show a 3.1-fold increase in CO2-eq emissions over a 100-year horizon, with the effect increasing with global warming intensity. Climate warming has stimulated phytoplankton growth in many lakes worldwide, which, in turn, can feed back CO2-eq and create a positive feedback loop between them. In lakes where phytoplankton is negatively impacted by climate warming, the CO2-eq feedback capacity may diminish gradually with the ongoing climate warming.

Mediterranean seagrasses provide essential coastal protection under climate change, Agulles et al., Scientific Reports:

Seagrasses are vital in coastal areas, offering crucial ecosystem services and playing a relevant role in coastal protection. The decrease in the density of Mediterranean seagrasses over recent decades, due to warming and anthropogenic stressors, may imply a serious environmental threat. Here we quantify the role of coastal impact reduction induced by seagrass presence under present and future climate. We focus in the Balearic Islands, a representative and well monitored region in the Mediterranean. Our results quantify how important the presence of seagrasses is for coastal protection. The complete loss of seagrasses would lead to an extreme water level (eTWL) increase comparable to the projected sea level rise (SLR) at the end of the century under the high end scenario of greenhouse gases emissions. Under that scenario, the eTWL could increase up to ~ 1.4 m, with 54% of that increase attributed to seagrass loss. These findings underscore the importance of seagrass conservation for coastal protection.

Misinformation exploits outrage to spread online, McLoughlin et al., Science:

We tested a hypothesis that misinformation exploits outrage to spread online, examining generalizability across multiple platforms, time periods, and classifications of misinformation. Outrage is highly engaging and need not be accurate to achieve its communicative goals, making it an attractive signal to embed in misinformation. In eight studies that used US data from Facebook (1,063,298 links) and Twitter (44,529 tweets, 24,007 users) and two behavioral experiments (1475 participants), we show that (i) misinformation sources evoke more outrage than do trustworthy sources; (ii) outrage facilitates the sharing of misinformation at least as strongly as sharing of trustworthy news; and (iii) users are more willing to share outrage-evoking misinformation without reading it first. Consequently, outrage-evoking misinformation may be difficult to mitigate with interventions that assume users want to share accurate information.

Increasingly Active Wildfire Seasons Threaten the Sustainability of Forest-Backed Carbon Offset Programs, Badgley, Global Change Biology:

In 2024, wildfires burned a record number of forests participating in California's forest offset program, exposing the danger of relying on forests to slow climate change. While California maintains a reserve of offset credits—known as a “buffer pool”—that is intended to safeguard against such carbon losses, the growing frequency, and severity of wildfires threatens to undermine the program's environmental goals.

From this week's government/NGO section:

Aligning with Net Zero in the PR & Advertising Sector, InfluenceMap

The authors analyze the corporate clients of the Big Six public relations and advertising agency holding companies – Dentsu, Havas, IPG, Publicis, Omnicom, and WPP. Client mapping of the 'Big Six' reveals significant potential ‘conflicts of climate interest’, where clients of the same holding company have opposing objectives in their climate policy advocacy. Using available Ad / PR agency client lists, the authors categorize clients with a traffic light system: Obstructive (Red), Partially Misaligned (Amber), Partially Aligned (Yellow), or Supportive (Green) in their climate policy engagement. While several of the Big 6 holding companies have strategies to work with clients to promote ‘low-carbon' or ‘sustainable’ products to the market, none have developed science-based methodologies to ensure these products align with a 1.5°C future.

Selling Hot Air. Lessons from how Shell’s flagship carbon capture project sold $200M of credits for reductions that never happened, Greenpeace Canada

Shell’s flagship carbon capture project has made over $200 million (CAD) selling emissions credits for reductions that never happened. The findings come as Canadian oil sands companies advertise carbon capture and storage (CCS) as a solution to oil sands pollution while lobbying against regulations that would cap emissions from the sector.

Safeguarding International Climate Protection Against the Trump Agenda. What Germany and the EU Can Do Now, Vinke et al., German Council on Foreign Relations

International climate protection is in trouble. A second Trump presidency will derail US climate leadership, leading to a withdrawal from the Paris Agreement and reducing international climate finance. Therefore, the EU and Germany must step up, leading by expanding green tech development and strengthening partnerships with key global players.

133 articles in 56 journals by 767 contributing authors

Physical science of climate change, effects

A positive atmospheric feedback on the North Atlantic warming hole, Kramer et al., Scientific Reports Open Access 10.1038/s41598-024-80381-7

Constraining net long-term climate feedback from satellite-observed internal variability possible by the mid-2030s, Uribe et al., Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics Open Access 10.5194/acp-24-13371-2024

Estimated human-induced warming from a linear temperature and atmospheric CO2 relationship, Jarvis & Forster, Nature Geoscience Open Access 10.1038/s41561-024-01580-5

Irreversible changes in the sea surface temperature threshold for tropical convection to CO2 forcing, Park et al., Communications Earth & Environment Open Access 10.1038/s43247-024-01751-7

Can desalination quench agriculture’s thirst?

Posted on 4 December 2024 by Guest Author

This article by Lela Nargi originally appeared in Knowable Magazine, a nonprofit publication dedicated to making scientific knowledge accessible to all. Sign up for Knowable Magazine’s newsletter.

Ralph Loya was pretty sure he was going to lose the corn. His farm had been scorched by El Paso’s hottest-ever June and second-hottest August; the West Texas county saw 53 days soar over 100 degrees Fahrenheit in the summer of 2024. The region was also experiencing an ongoing drought, which meant that crops on Loya’s eight-plus acres of melons, okra, cucumbers and other produce had to be watered more often than normal.

Loya had been irrigating his corn with somewhat salty, or brackish, water pumped from his well, as much as the salt-sensitive crop could tolerate. It wasn’t enough, and the municipal water was expensive; he was using it in moderation and the corn ears were desiccating where they stood.

The hidden threat from rising coastal groundwater

Ensuring the survival of agriculture under an increasingly erratic climate is approaching a crisis in the sere and sweltering Western and Southwestern United States, an area that supplies much of our beef and dairy, alfalfa, tree nuts and produce. Contending with too little water to support their plants and animals, farmers have tilled under crops, pulled out trees, fallowed fields and sold off herds. They’ve also used drip irrigation to inject smaller doses of water closer to a plant’s roots, and installed sensors in soil that tell more precisely when and how much to water.

In the last five years, researchers have begun to puzzle out how brackish water, pulled from underground aquifers, might be de-salted cheaply enough to offer farmers another water resilience tool. Loya’s property, which draws its slightly salty water from the Hueco Bolson aquifer, is about to become a pilot site to test how efficiently desalinated groundwater can be used to grow crops in otherwise water-scarce places.

Desalination renders salty water less so. It’s usually applied to water sucked from the ocean, generally in arid lands with few options; some Gulf, African and island countries rely heavily or entirely on desalinated seawater. Inland desalination happens away from coasts, with aquifer waters that are brackish — containing between 1,000 and 10,000 milligrams of salt per liter, versus around 35,000 milligrams per liter for seawater. Texas has more than three dozen centralized brackish groundwater desalination plants, California more than 20.

Such technology has long been considered too costly for farming. Some experts still think it’s a pipe dream. “We see it as a nice solution that’s appropriate in some contexts, but for agriculture it’s hard to justify, frankly,” says Brad Franklin, an agricultural and environmental economist at the Public Policy Institute of California. Desalting an acre-foot (almost 326,000 gallons) of brackish groundwater for crops now costs about $800, while farmers can pay a lot less — as little as $3 an acre-foot for some senior rights holders in some places — for fresh municipal water. As a result, desalination has largely been reserved to make liquid that’s fit for people to drink. In some instances, too, inland desalination can be environmentally risky, endangering nearby plants and animals and reducing stream flows.

But the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, along with a research operation called the National Alliance for Water Innovation (NAWI) that’s been granted $185 million from the Department of Energy, have recently invested in projects that could turn that paradigm on its head. Recognizing the urgent need for fresh water for farms — which in the U.S. are mostly inland — combined with the ample if salty water beneath our feet, these entities have funded projects that could help advance small, decentralized desalination systems that can be placed right on farms where they’re needed. Loya’s is one of them.

U.S. farms consume over 83 million acre-feet (more than 27 trillion gallons) of irrigation water every year — the second most water-intensive industry in the country, after thermoelectric power. Not all aquifers are brackish, but most that are exist in the country’s West, and they’re usually more saline the deeper you dig. With fresh water everywhere in the world becoming saltier due to human activity, “we have to solve inland desal for ag … in order to grow as much food as we need,” says Susan Amrose, a research scientist at MIT who studies inland desalination in the Middle East and North Africa.

Brackish (slightly salty) groundwater is found mostly in the Western United States. (Image credit: J.S. Stanton et al. / USGS)

That means lowering energy and other operational costs; making systems simple for farmers to run; and figuring out how to slash residual brine, which requires disposal and is considered the process’s “Achilles’ heel,” according to one researcher.

The last half-decade of scientific tinkering is now yielding tangible results, says Peter Fiske, NAWI’s executive director. “We think we have a clear line of sight for agricultural-quality water.”

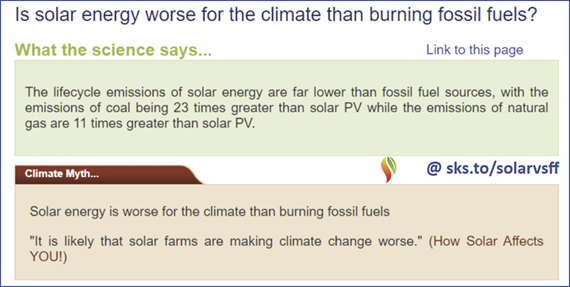

Sabin 33 #5 - Is solar energy worse for the climate than burning fossil fuels?

Posted on 3 December 2024 by BaerbelW

On November 1, 2024 we announced the publication of 33 rebuttals based on the report "Rebutting 33 False Claims About Solar, Wind, and Electric Vehicles" written by Matthew Eisenson, Jacob Elkin, Andy Fitch, Matthew Ard, Kaya Sittinger & Samuel Lavine and published by the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia Law School in 2024. Below is the blog post version of rebuttal #5 based on Sabin's report.

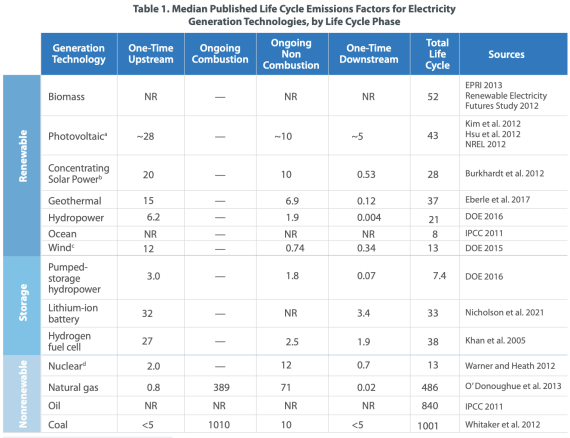

There is overwhelming evidence that the lifecycle emissions1 of solar energy are far lower than those of all fossil fuel sources, including natural gas2. On average, it takes only three years after installation for a solar panel to offset emissions from its production and transportation. Modern solar panels have a functional lifecycle of 30–35 years, allowing more than enough time to achieve carbon neutrality and generate new emissions-free energy3.

A National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) report released in 2021 examined “approximately 3,000 published life cycle assessment studies on utility-scale electricity generation from wind, solar photovoltaics, concentrating solar power, biopower, geothermal, ocean energy, hydropower, nuclear, natural gas, and coal technologies, as well as lithium-ion battery, pumped storage hydropower, and hydrogen storage technologies.” The report found widespread agreement that all modes of solar power have total lifecycle emissions significantly below those of all fossil fuels. The report found specifically that the total lifecycle emissions for solar photovoltaic (PV) and concentrating solar power (CSP) panels were 43 and 28 grams of CO2-eq/KWh (carbon dioxide-equivalents per kilowatt-hour), respectively. Coal, by contrast, generated lifecycle emissions of 1,001 grams of CO2-eq/KWh, and natural gas generated lifecycle emissions of 486 grams of CO2-eq/KWh.

Figure 1: Total lifecycle emissions for different energy sources. Source: NREL.

To be fair, there are some outlier studies. For example, one study examined a worst-case scenario in which the coal-powered manufacture of inefficiently sized solar PV cells may contribute to greater lifecycle emissions than the cleanest and most efficient fossil fuel plants (Torres & Petrakopoulou 2022). However, the conclusion that solar is worse for the climate than fossil fuels is not backed up by NREL’s more extensive survey.

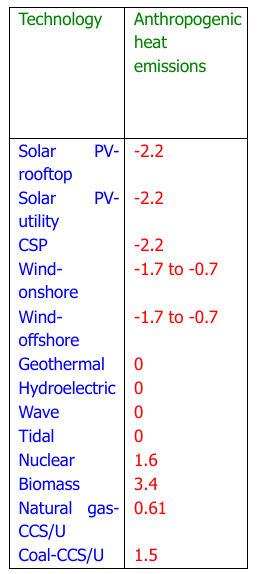

In addition to having smaller greenhouse gas emissions, solar power likewise outperforms fossil fuels in minimizing direct heat emissions. A 2019 Stanford publication notes that, for solar PV and CSP, net heat emissions are in fact negative, because these technologies “reduce sunlight to the surface by converting it to electricity,” ultimately cooling “the ground or a building below the PV panels.”4 The study found that rooftop and utility-scale solar PV have heat emissions equivalent to negative 2.2 g-CO2e/kWh-electricity, compared to the positive heat emissions associated with natural gas, nuclear, coal, and biomass.

Figure 3: The 100-year CO2e emissions impact associated with different energy sources’ heat emissions, measured in g-CO2e/kWh-electricity. Source: M.Z. Jacobson (reproduced and adapted with permission)

Looking at academic scholarship from outside of the United States, a 2022 analysis from India’s Hirwal Education Trust’s College of Computer Science and Information Technology describes the global impact of solar panel heat emissions as "relatively small".5

Arguments

Arguments

Tacuarembó, Uruguay. (Image credit: Getty Images)

Tacuarembó, Uruguay. (Image credit: Getty Images)