An ice sheet forms when snow falls on land, compacts into ice, and forms a system of interconnected glaciers which gradually flow downhill like play-dough. In Antarctica, it is so cold that the ice flows right into the ocean before it melts, sometimes hundreds of kilometres from the coast. These giant slabs of ice, floating on the ocean while still attached to the continent, are called ice shelves.

For an ice sheet to have constant size, the mass of ice added from snowfall must equal the mass lost due to melting and calving (when icebergs break off). Since this ice loss mainly occurs at the edges, the rate of ice loss will depend on how fast glaciers can flow towards the edges.

Ice shelves slow down this flow. They hold back the glaciers behind them in what is known as the “buttressing effect”. If the ice shelves were smaller, the glaciers would flow much faster towards the ocean, melting and calving more ice than snowfall inland could replace. This situation is called a “negative mass balance”, which leads directly to global sea level rise.

Ice shelves are perhaps the most important part of the Antarctic ice sheet for its overall stability. Unfortunately, they are also the part of the ice sheet most at risk. This is because they are the only bits touching the ocean. And the Antarctic ice sheet is not directly threatened by a warming atmosphere – it is threatened by a warming ocean.

The atmosphere would have to warm outrageously in order to melt the Antarctic ice sheet from the top down. Snowfall tends to be heaviest when temperatures are just below 0°C, but temperatures at the South Pole rarely go above -20°C, even in the summer. So atmospheric warming will likely lead to a slight increase in snowfall over Antarctica, adding to the mass of the ice sheet. Unfortunately, the ocean is warming at the same time. And a slightly warmer ocean will be very good at melting Antarctica from the bottom up.

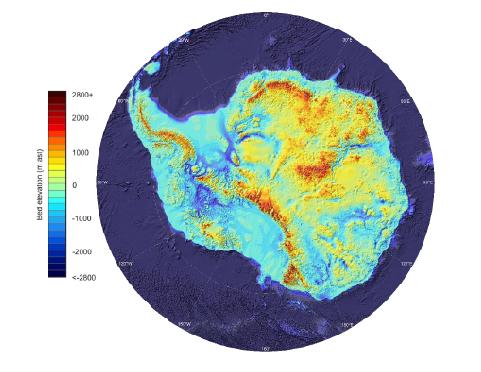

This is partly because ice melts faster in water than it does in air, even if the air and the water are the same temperature. But the ocean-induced melting will be exacerbated by some unlucky topography: over 40% of the Antarctic ice sheet (by area) rests on bedrock that is below sea level.

Elevation of the bedrock underlying Antarctica. All of the blue regions are below sea level. (Figure 9 of Fretwell et al.)

This means that ocean water can melt its way in and get right under the ice, and gravity won’t stop it. The grounding lines, where the ice sheet detaches from the bedrock and floats on the ocean as an ice shelf, will retreat. Essentially, a warming ocean will turn more of the Antarctic ice sheet into ice shelves, which the ocean will then melt from the bottom up.

This situation is especially risky on a retrograde bed, where bedrock gets deeper below sea level as you go inland – like a giant, gently sloping bowl. Retrograde beds occur because of isostatic loading (the weight of an ice sheet pushes the crust down, making the tectonic plate sit lower in the mantle) as well as glacial erosion (the ice sheet scrapes away the surface bedrock over time). Ice sheets resting on retrograde beds are inherently unstable, because once the grounding lines reach the edge of the “bowl”, they will eventually retreat all the way to the bottom of the “bowl” even if the ocean water intruding beneath the ice doesn’t get any warmer. This instability occurs because the melting point temperature of water decreases as you go deeper in the ocean, where pressures are higher. In other words, the deeper the ice is in the ocean, the easier it is to melt it. Equivalently, the deeper a grounding line is in the ocean, the easier it is to make it retreat. In a retrograde bed, retreating grounding lines get deeper, so they retreat more easily, which makes them even deeper, and they retreat even more easily, and this goes on and on even if the ocean stops warming.

Which brings us to Terrifying Paper #1, by Rignot et al. A decent chunk of West Antarctica, called the Amundsen Sea Sector, is melting particularly quickly. The grounding lines of ice shelves in this region have been rapidly retreating (several kilometres per year), as this paper shows using satellite data. Unfortunately, the Amundsen Sea Sector sits on a retrograde bed, and the grounding lines have now gone past the edge of it. This retrograde bed is so huge that the amount of ice sheet it underpins would cause 1.2 metres of global sea level rise. We’re now committed to losing that ice eventually, even if the ocean stopped warming tomorrow. “Upstream of the 2011 grounding line positions,” Rignot et al., write, “we find no major bed obstacle that would prevent the glaciers from further retreat and draw down the entire basin.”

They look at each source glacier in turn, and it’s pretty bleak:

- Pine Island Glacier: “A region where the bed elevation is smoothly decreasing inland, with no major hill to prevent further retreat.”

- Smith/Kohler Glaciers: “Favorable to more vigorous ice shelf melt even if the ocean temperature does not change with time.”

- Thwaites Glacier: “Everywhere along the grounding line, the retreat proceeds along clear pathways of retrograde bed.”

Only one small glacier, Haynes Glacier, is not necessarily doomed, since there are mountains in the way that cut off the retrograde bed.

From satellite data, you can already see the ice sheet speeding up its flow towards the coast, due to the loss of buttressing as the ice shelves thin: “Ice flow changes are detected hundreds of kilometers inland, to the flanks of the topographic divides, demonstrating that coastal perturbations are felt far inland and propagate rapidly.”

It will probably take a few centuries for the Amundsen Sector to fully disintegrate. But that 1.2 metres of global sea level rise is coming eventually, on top of what we’ve already seen from other glaciers and thermal expansion, and there’s nothing we can do to stop it (short of geoengineering). We’re going to lose a lot of coastal cities because of this glacier system alone.

Terrifying Paper #2, by Mengel & Levermann, examines the Wilkes Basin Sector of East Antarctica. This region contains enough ice to raise global sea level by 3 to 4 metres. Unlike the Amundsen Sector, we aren’t yet committed to losing this ice, but it wouldn’t be too hard to reach that point. The Wilkes Basin glaciers rest on a system of deep troughs in the bedrock. The troughs are currently full of ice, but if seawater got in there, it would melt all the way along the troughs without needing any further ocean warming – like a very bad retrograde bed situation. The entire Wilkes Basin would change from ice sheet to ice shelf, bringing along that 3-4 metres of global sea level rise.

It turns out that the only thing stopping seawater getting in the troughs is a very small bit of ice, equivalent to only 8 centimetres of global sea level rise, which Mengel & Levermann nickname the “ice plug”. As long as the ice plug is there, this sector of the ice sheet is stable; but take the ice plug away, and the whole thing will eventually fall apart even if the ocean stops warming. Simulations from an ice sheet model suggest it would take at least 200 years of increased ocean temperature to melt this ice plug, depending on how much warmer the ocean got. 200 years sounds like a long time for us to find a solution to climate change, but it actually takes much longer than that for the ocean to cool back down after it’s been warmed up.

This might sound like all bad news. And you’re right, it is. But it can always get worse. That means we can always stop it from getting worse. That’s not necessarily good news, but at least it’s empowering. The sea level rise we’re already committed to, whether it’s 1 or 2 or 5 metres, will be awful. But it’s much better than 58 metres, which is what we would get if the entire Antarctic ice sheet melted. Climate change is not an all-or-nothing situation; it falls on a spectrum. We will have to deal with some amount of climate change no matter what. The question of “how much” is for us to decide.

Arguments

Arguments

There may be another factor at play here. As the underside of the sloping ice sheet melts, it mixes with the adjacent sea water. This less salty water will rise up the underside of the upsloping ice and debouch on the surface of the sea, and be kept there by its lesser density. This will suck sea water in to replace it with the sea water carrying its burden of calories. The deeper the grounding line, the greater this effect should be just as an air lift is more effective, the deeper its mouth. It should be possible to get a handle on the metrick of this process by putting in place current measuring and salinity measuring instruments on the underside of the ice shelves.

Perhaps this should be added to the list of scary papers:

LINK

Arctic ice shelves aren't faring any better. The loss observed is nothing short of staggering.

[JH] Link activated.

[RH] Link shortened.

GRL paper here:

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/2014GL062255/abstract

[JH] Link activated.

Sorry. I'm not terrified. Concerned, yes. But the use of 'terrified' is hyperbolic.

Terror requires more immediacy. In South Africa if your neighbor is executed with a burning tire, you can be terrified. In WWII when you woke up to find that the Ghurkas had come in and slit the throat of the soldier sleeping one bunk over, you can be terrified. When the tail of the plane you are in falls off you can be terrified. I don't think that anyone is terrified by an event that is decades from affecting their life in a significant way. The rationists will be concerned. But they are, what, 10% of the population as a whole.

In this battle for people's minds, as rationalists we have to use language rationally. If we speak in continuous hyperboly we get caught in the Suzuki syndrome. (David Suzuki has made enough exaggerated forecasts of doom that didn't come to pass that I no longer give him any credance whatever.)

***

A second part of this battle for mindshare is the general lack of immediacy. Most people won't make a money saving home improvement unless it will pay for itself in 3-5 years. (The flurry of PV installs appears to contradict this, but the percentage of houses with PV is still small, and correlates well to areas where they pay off quickly; are in regions that have suffered rolling outages; and have a high percentage of high tech jobs)

To get mindshare, you need immediacy. Remember that meme for task management about categorizing things as unimportnant versus important, and also as non-urgent vs urgent. People tend to do those things that are urgent requiring reactive immediate action, over things that are important but whether you do something this week or next week isn't as critical.

(It's hard to remember when you are up to your ass in alligators that your objective is to drain the swamp.)

To be succesful you need to increase the urgency generally in people's minds.

Locally (Alberta) the biggest event has been the Moutain Pine Beetle outbreak. (While the rest of the province lives on oil revenue...)

If you live in a coastal city, draw a map of the new coast line with a 20 cm sea rise. Get city planners to start thinking about this.

It doesn't help that apart from the generalities the boffins with the computers aren't very good at at making specific predictions. Will my climate in central Alberta get warmer? Highly probable. Wetter? Maybe. But the extra warmth will make the climate in effect drier. That's the current best guess, but the associated numbers are rife with uncertainty. It's hard enough to gamble with known probabilities.

(In passing, as a tree farmer, I make a point of planting trees that are 'out of zone'. Trees that would normally not grow here but rather in a warmer, drier climate. )

With rising temperatures we should get larger patches of ocean that are above the critical temperature to power the heat engine that is a hurricane. We should be getting more frequent tornadoes in a longer season. I haven't checked recently, neither are forms of weather that have any immediacy.

[Rob P] - The inability to recognize future threats, as opposed to immediate ones, is arguably the largest contributor to inaction on climate policy. But misinformation propagated by the mainstream media probably doesn't help either.

Societal change, when it does happen, can happen awfully fast though. Witness gay marriage for instance. After years of banging their heads against a brick wall, gay rights activists saw rapid change occur around the world. We'll need something of even larger scale to prevent the worst consequences of global warming and ocean acidification from taking place.

sgbotsford - god points you make. I wrote a Huffington Post/Common Dreams article about our human propensity not to be responsive to danger until it has reached a certain point of immediacy and suffering. In my personal experience through multiple serious illnesses, I did not begin to respond BEFORE tipping points were triggered until I'd learned through hard and repeated experience. Given the relatively "slowly" developing effects of climate change...it puts us in a very tough spot. Here is the article, if you are interested: www.commondreams.org/views/2014/02/28/through-climate-portal-humanitys-tragic-flaw

This work adds to the understanding that authorities have on the unintended consequences of technological systems using fossil fuels. It helps them to make responsible decisions about implemetation of adaption measures to cope with expectations. For example, authorities in New York, London and the Netherlands are planning to use appreciable resources to provide a degree of protection from sea level rise and storm surges.

Well, OK, concerned, but not terrified. Last time I was terrified was when I read Hansen's paper on the increasing 3-sigma heat wave events. There is a strong signal of food production reductions where these events occur. I suspect food (in)security will hit us harder, faster than sea level rise.

'Concerned' is justified, 'terrified' is not. These ice shelves should give us plenty of time to move out of the house before it is inundated. The terror comes later when you realize your neighbors have a limited capacity for compassion.

OK, now I'm scared again.

Climate variation explains a third of global crop yield variability

sgbotsford, good argument on logical response, although I do feel terrified when I consider the implication of the coming changes for my kids and grandkids. When 40% of civilization's infrastructure is threatened or destroyed, and when reconstruction will worsen the case, it will be terrifying. In net, it may be good for Canadians, but for the rest of the world it is bad. Terrifying is appropriate if one can see beyond one's little life, which this problem requires.

I guestimate we will settle at about 4 meters for the first century of this challenge. Just for reference I roughly calculated what 1% of insolation retention would do to the cryosphere, if all that additional heat went there. I was guessing centuries, or millennia for 20 meters of sea level rise. If my back of the envelope is right, its only about 14 years of such retention rate. What is the maximum that increased CO2 and methane and other GWG can cause? We don't know. Fortunately, just like Pluvinergy can resolve our energy issues, Pluvicopia, not published becasue of patent processes, can resolve 20 meters of sea level rise in 500 years. These technologies are geoengineering of the good sort, but it is totaly upon us to decide what this means. If we convert the deserts into gardens, what kind of moral statement is that making? Etc.

I wish people would stop talking about how we need to do this and that to stop global warming. We have already done enough that global warming is a given. It will happen. If we stopped every emission today, we will still have a warming climate for the next 25 to 50 years. In that regard, it really doesn't make that much difference who or what caused it. What we need is to start thinking about how to cope with it. Shifting crops, drought, insect infestations, disease migration, lost animal habitat and extinctions, population migrations, weather pattern adaptation, and so on.

If we stopped trying to place blame and simply look at the trends, perhaps we could begin the process of adapting. Unfortunately, I have very little faith that we will even begin that process until people are dying on a large scale from famine, drought and conflict.

There is roughtly $15.7 trillion of sellable oil in central Canada's tar sands. If the XL pipeline is not built, then they will resort to trucks or trains. There is no way that the owners, investors and the government will agree to leave $15.7 trillion in the ground just because of the damage it will do to the atmosphere. Money is power and money has absolute control over the US government and msot of the Canadian government. Even if Saudia Arabia is successful in its current effort to undersell oil so that the tar sands are not profitable now, there will come a time in the future when it will be again and eventually they will sell all 178 billion bbls of tar sand oil. The money involved is so large that world economies would collapse if we suddenly stopped using oil.

So let's stop talking about who or why or reductions and get on with simple survival. If we don't, there are going to be a lot fewer of us to continue the arguing.

Paxinterra,

When there are two rules for getting out of a hole that you have dug.

1) Do everything you can to get out of the hole.

2) Stop digging deeper.

If the oil sands and other alternate fossil fuels are all dug up it will be a disaster. We have to stop digging and take all measures to deal with the problem. Today, in the developed countries, adaptation is not too bad to deal with. We focus on stopping digging to prevent the problem from growing out of control.

Paxinterra wrote: "I have very little faith that we will even begin that process [adapting to climate change] until people are dying on a large scale from famine, drought and conflict."

The process of adapting to anthropogenic climate change began decades ago... people have been "dying on a large scale from famine, drought, and conflict" for thousands of years now. How many of the recent deaths from those (and other) causes are due to climate change is a matter of some debate, but certainly it has already been a factor.

When New York city finally put in better flooding control mechanisms after Hurricane Sandy... that was adapting to climate change. The flooding from the storm wouldn't have been nearly as bad if not for the sea level rise from climate change. Without that extensive flooding damage the city wouldn't have (and for decades hadn't) bothered to act. The same cycle can be seen all around the world. Humans adapt to their environment... it's automatic. We could do so better if we more often anticipated future changes and prepared for them in advance, but the idea that we haven't begun adapting to climate change is inaccurate.

As to your suggestion that we should not worry about reducing CO2 emissions because all of the tar sands oil and other fossil fuels will inevitably be burned eventually... if that is true then "there are going to be a lot fewer of us" no matter what attempts we make at adaptation. Burning all the known remaining 'easily accessible' oil and/or coal, let alone any further supplies made available by future technology and exploration would wipe out most of the human race. Fortunately, it seems fairly clear that fossil fuels are already on the way out... with no 'world economies collapsing' as a result.

PaxInterra - We certainly need to engage in adaptation. But there's no reason to throw up our hands and say that mitigation is useless. Every bit of mitigation, of avoiding additional emissions, reduces needed adaptation down the line. And it's considerably cheaper to invest in mitigation now than that additional adaptation later.

Not to pile on here... but I believe PaxInterra's response is more an emotional one than a fact based one. If KXL were not important to the extraction rate of the tar sands, then they really wouldn't care. As it is, investors are pulling out of tar sands projects because it's looking less profitable. If we can get carbon taxes installed, then those FF sources of energy become less competitive and tar sands become even less attractive.

There are lots of reasons to have a positive outlook on how things are going to play out in the coming 10-15 years. Taking a defeatist attitude only plays into the hands of the FF industry.

Chris G @7

when you say, "I suspect food (in)security will hit us harder, faster than sea level rise."

realize that the syrian destabilization and much of the political unrest in the region was catapaulted by an historic regional drought that drove rural populations into the cities looking for work and caused an explosion in the price of grain.

The food insecurity issue is not as significant as the related political unrest, economic destabilzation and societal dissolution caused by (associated) regional conflict. This "threat multiplier" of climate change is why the U.S. military considers global warming to be the greatest existential threat to the U.S. today.

Chris G

From the paper "in substantial areas of the global breadbaskets, >60% of the yield variability can be explained by climate variability". Yikes!!!

jja

"The food insecurity issue is not as significant as the related political unrest...."

Not yet, Perhaps say it is currently a 'fear of food insecurity' issue at present. But a few decades from now actual food insecurity may come to dominate. Then all bets are off, the world starts to go ape!

yep, that's the one. It's been projected that the Arctic warms way faster than the rest of the globe. Greenland partially melts which raises the sea level which twists the West Antarctic Ice Sheet which cracks the buffer keeping the Antarctic glaciers from melting. Thus they melt and thus the sea level rises to the level where many current ports become inoperable thus the commerce stops thus follows the economic meltdown thus the world ends.

I really should stop writing in hangover.

JJA,

I don't really separate the two. I think that, historically, whenever people have a choice between starving and raiding, they raid every time. I don't know if you would consider the unrest in the Middle East as raiding, but it certainly is violence between groups of people.

In my mind, there is a connection between the Russian heat wave of 2010, their failed harvest, their ban on wheat exports, the rising food prices in the Middle East (where the Russians sell most of their wheat), and the food price riots/unrest in Tunisia where the "Arab Spring" started. Others will think it is a thin thread.

I've also had an opportunity to speak with agricultural biologists from Syria; they are experiencing a dramatic decline in rain, making it difficult to get good yields. I suspect the unrest/violence in the region is causally related to declining ability to feed the population. Unfortunately, violence in the region multiplies the problem of trying to grow food.

Here is something from the World Food Programme along these lines.

Basically, the way I see it, heat waves and changes in precipitation patterns will make it more difficult to grow food. Food prices increase. Food is not something that you can go without; so, areas where food costs rise see declines in standards of living. Enough of a decline leads to civil unrest, civil unrest exacerbates the food security problem, and you get what biologists might call an overcorrection in population density.

Glenn,

This will not happen everywhere at once. Areas where food cost is a small fraction of income will be stable far longer than areas where food costs are a large portion of income. Personally, I think we are already seeing the start of the trouble with rising population and crop yield instability.