How much does animal agriculture and eating meat contribute to global warming?

Posted on 13 November 2020 by ZackChester

This post is an updated intermediate rebuttal to the myth "Animal agriculture account for 51% of CO2 emissions". It was written by Zack Chester as part of the George Mason University class Understanding and Responding to Climate Misinformation, combining climate science and communication best practices to debunk common climate myths.

The three largest contributors to global greenhouse gas emissions are as follows:

- Burning fossil fuels for electricity and heat (31% of annual global human greenhouse gas emissions);

- Transportation (15%); and

- Manufacturing (12.4%).

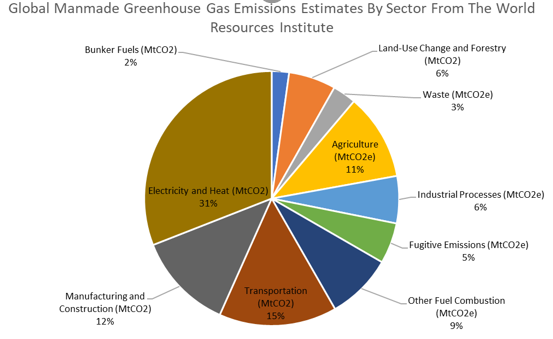

The fourth largest contributor is animal agriculture accounting for 11% of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions according to estimates from the World Resources Institute, as shown in Figure 1.

One myth argues that animal agriculture is the greatest contributor to global greenhouse gas emissions, claiming it accounts for 51% of annual global GHG emissions.

|

Figure 1: Global manmade GHG emissions by sector reported by the World Resources Institute. Electricity and heat make the largest contribution at 31% with animal agriculture making up 11%. |

While animal agriculture is a significant contributor to GHG emissions, it is not actually the biggest contributor, as the myth claims. The calculations used to get the 51% of global GHG emissions are, at times, inaccurate or inappropriate, leading ultimately to a misrepresentation of the impact of animal agriculture. This rebuttal will be split into two main parts, the first discussing the actual causes of GHG emissions and the second discussing how the non-peer reviewed report by Goodland and Anhang arrives at the 51% number.

Burning Fossil Fuels Really Accounts For The Majority Of Emissions

All estimates of carbon emissions have uncertainty, but different credible sources agree that burning fossil fuels for heat and energy is the largest contributor to global GHG emissions. Independent reports, some of which will be discussed in the following paragraphs, use different methodologies to arrive at the contribution of global GHG emissions. These differences are largely due to things like how the variables are grouped, such as grouping land use with animal agriculture or combining manufacturing and production with industrial processes. It is important to note, however, that while there are differences in these figures and numbers, the reports consistently conclude that burning fossil fuels for energy and heat is the largest contributor.

The World Resources Institute is a global research nonprofit that studies environmental sustainability, economic opportunity, and human well-being. The World Resources Institutes Climate Analysis Indicators Tool, a tool designed to analyze GHG emissions by sector and country, concludes that the energy sector accounts for the majority of emissions, around 72%. Within that 72%, are electricity and heat, transportation, and manufacturing which account for 31%, 15%, and 12.4% of annual global greenhouse gas emissions, respectively. Animal agriculture accounts for 11% of the GHG emissions (World Resources Institute). Figure 1 shows a 2013 compilation of these estimates put together using data from the World Resources Institute, showing that the energy sector accounts for the majority of these emissions.

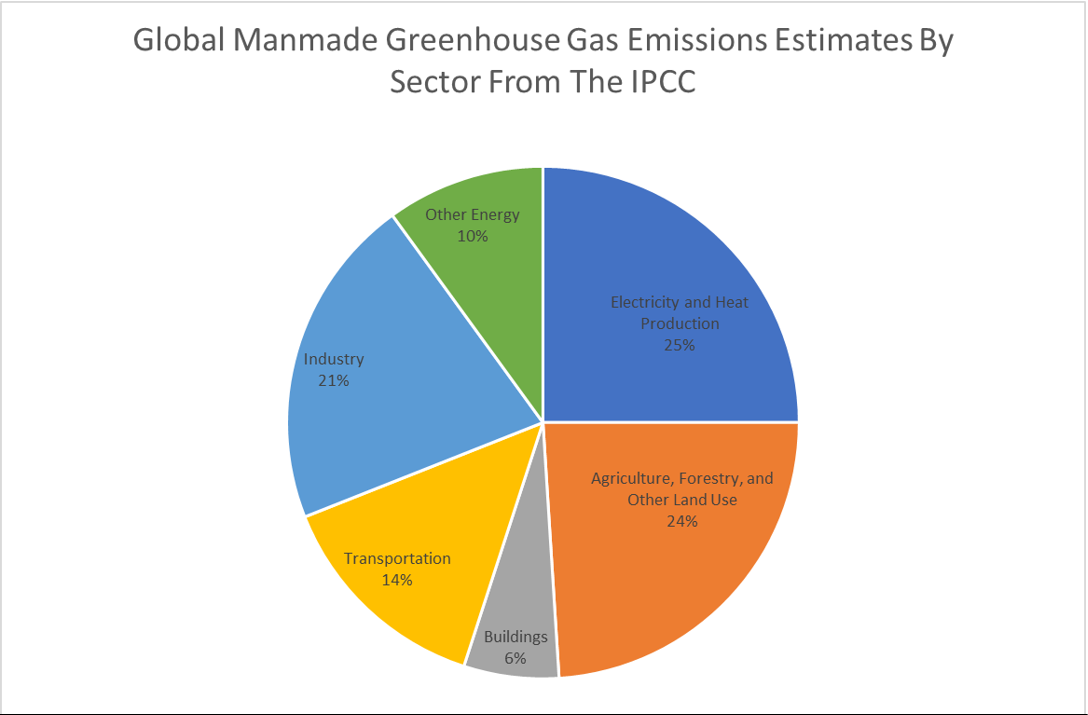

This is not the only estimate of various sectors impact on global emissions. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is a body of the United Nations focused on studying and understanding human induced climate change. The United States Environmental Protection Agency reports global emissions in the same way that is reported by the IPCC, shown in Figure 2. By these estimates, electricity and heat production account for 25% of global emissions, agriculture, forestry, and land use make up 24%, industry 21%, and transportation 14%. These estimates are different from those noted before, but the reason for the difference is important.

|

Figure 2: Global manmade GHG emissions by sector reported by the IPCC, electricity and heat production make the largest contribution at 25% followed by animal agriculture, forestry, and other land use making up 24% (IPCC). |

For the World Resources Institute and IPCC, the sources for their information and how the numbers are derived are publicly available, compiling reported data from across the globe. As mentioned before, the reason for the differences are largely in grouping. The following section will discuss how the 51% myth bases its numbers on exaggerations and uses completely different methodologies from both of these groups in deriving its numbers.

The 51% Figure Is Based On Poor Assumptions and Exaggeration

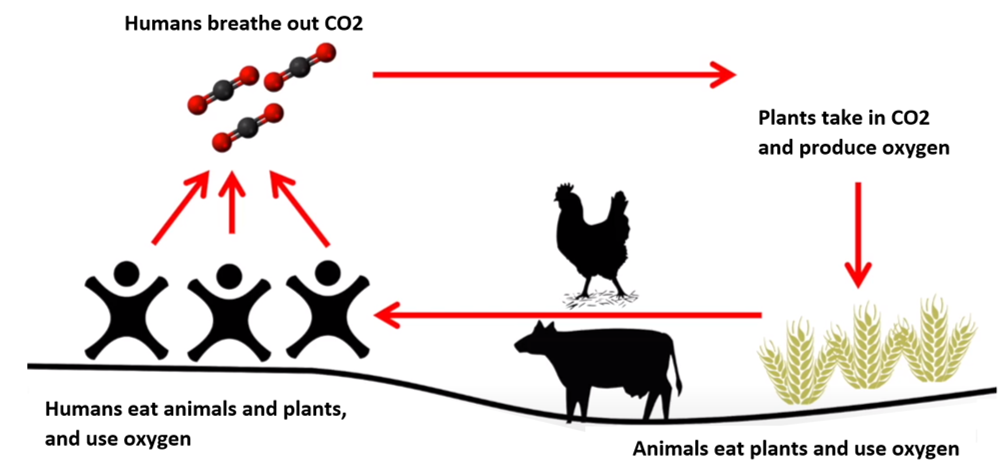

As mentioned above, the 51% claim comes from a non peer reviewed paper, containing a series of flaws and fallacies used in arriving at their number. A peer reviewed critique of the paper highlights many of the flaws that consistently exaggerate the effects of animal agriculture. One example is how the paper handles livestock respiration. When animals and humans breathe, CO2 is emitted into the atmosphere and taken in by plants, then converted to oxygen. We breathe and eat the plants and the cycle continues, so when we breathe out, we are returning CO2 that was already there. This is why human and animal respiration are excluded from carbon dioxide emission assessments, as the carbon cycle is accepted to be net zero over the span of years to decades.

Figure 3 helps illustrate the carbon cycle. If this paper chose to take a stance that animal respiration is not net zero, it is possible to account for animal respiration in the emission budget. However, it is also important to calculate the absorption and consumption of CO2 as well to quantify the imbalance due to respiration, which is not done. On top of that, and more pertinent to the matter, if the authors of the paper think that the carbon cycle is not net zero, it would also be necessary to include human respiration in the calculations to adequately assess the appropriate contribution of human CO2 emissions. They assume that the emissions of over 7.5 billion humans alive today are net zero, and livestock emissions are not, which is cherry picking. As is, the paper oversimplifies the issues, leading to a misrepresentation of animal agriculture's contribution to global GHG emissions. Accounting for these issues would cause a major change to the 51% value in the report, as over 26% of the reported emissions by animal agriculture come from animal respiration.

|

Figure 3: A simple diagram of the carbon cycle showing how humans and animals emit CO2 that is then used by plants to make oxygen, which are then eaten (modified from a chart made by Patrick Brown). |

Oversights of this sort occur throughout the paper. Another example is CO2 emissions from land and land use, which contributes to 8.2% of animal agriculture emissions. In the paper the myth partially arises from, an extra source of CO2 emissions is added to animal agriculture's contribution using a hypothetical ‘what-if scenario’. The paper postulates that if land for animal agriculture were converted to activities such as growing crops for humans or biofuel, there could be emissions savings. These potential savings were then added to the other sources of animal agriculture emissions and treated as a way that animal agriculture contributes to total GHG emissions.

This hypothetical approach is inconsistent with the way that the World Resources Institute and IPCC report global GHG emissions. It is a problematic approach because it then uses the total worldwide emissions that both of these sources report to derive its 51% as opposed to driving and reporting a different, larger, total worldwide GHG emissions total, as would be necessary. Other sources, like fossil fuel burning, are not scrutinized to the point of considering what emissions would be if they were also changed to meet these ‘what-if scenarios’, which would ultimately lead to a vastly different worldwide emission totals (Herrero et al 2011). That is not to discredit ‘what-if’ thought experiments - they can be helpful in outlining potential future changes. But in a study on actual current emissions, it is inconsistent and inappropriate to include them as emissions. Altogether, these errors consistently overestimate the impact of animal agriculture.

Everyone Can Help The Environment In Their Own Way

There is a lot of discussion on how animal agriculture impacts various countries differently. It is possible to cherry pick examples from countries and argue that animal agricultural emissions are far more (or less) impactful on emissions than global numbers show. However, just because there are some countries that show different contributions from animal agriculture than are shown in a look at the globe as a whole, it does not mean that animal agriculture is misrepresented globally.

Similarly, one oversimplifying argument is that even if animal agriculture is not the main cause of global emissions, going vegan is the easiest thing one as an individual can do to lower their impact on global emissions. This is a difficult argument to support or disprove, as the benefit and ease of going vegan comes down to personal choices as well as the region one lives in. Everyone lives a different life and a person’s health, their living situation, and personal choices all play a role in the impact that they can make in reducing GHG emissions. There is no cookie-cutter, one-size-fits-all solution as to what can be done. The best way that you can lower your impact on global emissions is to be cognizant of your actions and actively work to minimize activities that create emissions whenever possible. For anyone interested, a list of some ways you can modify your lifestyle is included here. While animal agriculture does not contribute most of the CO2 emissions, it is still a significant contributor. Nevertheless, creating misleading or erroneous statistics to push a false narrative is counterproductive and only serves to hurt the causes that one is seeking to advocate for.

Arguments

Arguments

I'm glad to see this article but I think you should reconsider your reference to Poore & Nemecek in the link posted above (LINK).

I applaud Poore and Nemecek for their efforts to collate and present this information but I believe that any study that uses 100 year emission factors for methane and does not account for the carbon sequestration potential of grazing land (using the best available current evidence) should not be cited without review and correction. Note that accounting for methane GWP correctly, and modelling livestock grazing using best practice (the Savory Institute and Regeneration International have good information on this) wouldn't just change the picture slightly, they would be likely to change the representation of livestock farming into a carbon sink. From review of Poore and Nemecek's Science article that the data has been taken from, you can see in the Erratum that they originally had underestimated the carbon sink potential for land not used for food, but neither in the report, nor the Erratum have they noted the carbon sink potential for grazing land. This is probably mostly because the study is a meta-analysis and understanding of soil microbiology has advanced in recent years so findings based on meta-analyses of outdated information are unlikely to reflect the best of evidence.

On the representation of methane GWP, methane has a half-life in the atmosphere of about 10 years, so if cattle herd sizes remain the same over the lifetime of methane in the atmosphere they will maintain the same amount of additional methane in the atmosphere year on year. In terms of their contribution to warming, this, in a very simplistic sense, is equivalent to a closed power station (LINK, LINK). Note that the number of cattle in Europe and North America is actually lower than it was in the 1960's whilst India has fewer cattle than it did in the 1980s, LINK, so their associated methane emissions have actually dropped. I put the misrepresentation of methane GWP down to laziness - it's much easier to apply a single figure per head of cattle than to look at how herd size has changed over time.

[RH] Shortened and activated links.

Worse yet, both actually omit the methane cycle, ie Methanotroph activity, but counting only emissions there too.

You could draw an almost identical graph as the one showing the CO2 cycle including both plants and animals, and simply adjust this by substituting CH4 for CO2 and Methanotrophs for plants. (the numbers vary, but the cycle is very similar)

Any analysis of methane emissions that omits methanotrophs is just as misleading as any analysis of CO2 emissions that omits plants.

Couting natural emissions only give misleading

Sorry the typos

Eating meat and dairy is by far the most nutritional elements to a diet you can do. To get all of what a meat and dairy dite provides otherwise in out of reach for the poorer half of the world population.

It is all about how the animals are raised. Concentrated industrial livestock production is neither healthy for people or the planet and only serves to enrich a small handful of individuals.

Safe, sound and humaine animal husbandry will provide the world with fulfilling jobs and complete nutrition.

I don't disagree with the fact that animal agriculture is not the largest producer of greenhouse gases as this article rightly points out. However, in terms of solutions to reduce global CO2 equivalent levels to what is needed to stay below 1.5degC IPCC target, animal agriculture plays a larger role than it appears at first (and second) glance.

Project Drawdown (https://www.drawdown.org/solutions/table-of-solutions) has a detailed list of well researched and vetted solutions to meet the IPCC 1.5 degC target ranked in order of gigatons of CO2 equivalent reduction. Fourth on the list is plant-rich diet yielding 92 gigatons CO2 reduction out of a total reduction target of 1576 gigatons (by 2050). Sixth on the list is tropical rainforest restoration yielding 85 gigatons.

The 4th and 6th ranked solutions happen to be closely related. The largest driver of deforestation of tropical forests is related to industrial animal agriculture; beef production and soybean production used mainly for livestock feed, rank 1 and 2, respectively, as drivers of deforestation (https://www.worldwildlife.org/magazine/issues/summer-2018/articles/what-are-the-biggest-drivers-of-tropical-deforestation).

Taken together, plant-based diet and the resultant reduction of the main driver of rainforest deforestation combine to top the list of solutions proposed by Project Drawdown with a combined reduction of 177 gigatons of CO2 equivalent. Of course, 177 gigatons reduction is only a tenth of what is needed in total, but unlike revamping the electrical generation system, the transportation systems or industrial process, often individuals can move toward a plant-based diet and policies can be enacted to encourage it with near term results.

I disagree with the conclusion that going vegan is the easiest thing one as an individual can do to lower their impact on global emissions is not worthy of recommendation. Of course, there will be exceptions depending on individual and regional situations, but as a general rule, policies that encourage plant-based diets should be strongly supported as this represents upwards of 10% of the overall solution to reach IPCC targets. It is also in many cases the simplest step individuals can take to make meaningful strides in reducing atmospheric CO2 equivalent.

In addition, from a health perspective, plant-based diet is consistently shown to produce better health outcomes (e.g. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26853923/) which can be an indirect help in this struggle.

Jef asserts: "Eating meat and dairy is by far the most nutritional elements to a diet you can do. To get all of what a meat and dairy dite provides otherwise in out of reach for the poorer half of the world population."

In other words a vegetarian diet is allegedly more expensive than a meat based diet.

This does not appear to be correct. Studies show a vegetarian diet is cheaper then a standard meat based diet as below. I just googled this quickly at random to get a feel for it. However it is fair to say it depends a lot on exactly what ingredients you use. Diets heavy in nuts could get expensive.

medicalxpress.com/news/2018-05-vegetarian-diet-good-youit.html

www.takepart.com/article/2015/10/12/vegetarian-diet-savings

I decided to also check this for New Zealand, out of interest. All prices per kilogram: Beef mince $16.00, Chicken thighs $13.00, fish $35.00 fresh, Fish $15.00 canned, rice $3.50, potato $3.00, Beans $3.00, carrots $4.00. Beef and chicken contain about 350 grams protein per 1kilo. Fish contains about 350 grams protein per 1 kilo fish. Beans contain about 200 grams protein per 1 kilo. I've ignored dairy for the sake of simplicity. It is not an essential in a diet. I've just chosen some key foods to get a rough first approximation of the issue.

It's clear that grains and vegetables are much cheaper than meat. Its clear that substituting canned fish and and equal quantity of beans for meat works out cheaper than meat alone. I'm assuming a vegetarian diet that combines fish and beans as a source of protein, for the sake of argument. I assume you would also need some multi vitamin supplements, but the cost per day is insignificant. The conclusion is a vegetarian diet is cheaper than a traditional meat based diet where I live, although not hugely cheaper.

However there are many things to consider. I'm not promoting a vegetarian diet as such, I just wanted the facts. FWIW I think a low meat diet makes sense with the rest of your protein from fish plus beans etcetera.

"It is all about how the animals are raised. Concentrated industrial livestock production is neither healthy for people or the planet and only serves to enrich a small handful of individuals."

Agreed, but its tricky because organic types of farming are currently typically 47% more expensive than traditional as below, particularly meat production. That is the hard reality. But as these farms scale up I would expect prices to drop.

www.consumerreports.org/cro/news/2015/03/cost-of-organic-food/index.htm

Ultimately we have to transition from industrial agriculture to something organic with less tilling, and much less use of industrial pesticides or we are going to really seriously undermine the biosphere, but it probably has to be a phased transition so that people can absorb the costs.

@5Ugern,

I am a big fan of project Drawdown in general, but there are some flaws in that analysis.

The biggest flaw is in claiming the top two drivers of rainforest deforestation is beef and soy used for other meat production. Well this analysis isn't precisely wrong per se, but as I mentioned above the elephant in the room is the over-production of corn and soy. They are #2 and #3 by the way. Number one is timber. ;-) But they could be considered the #1 and #2 reasons why they don't immediately replant after timbering.

Reducing meat consumption only means more production of corn and soy for biofuels, and the rainforests continue to fall. The real problem is the prime grasslands that could and should be producing forage for animals and a whole host of biology are largely already in commodity crop production, and not being grazed by animals. The industrialised system is NOT land efficient, it is labor efficient. This makes a huge difference and needs to be addressed or we will get nowhere.

Until we return the animals to the land where they belong, and eliminate the current industrialised agricultural paradigm, we will get nowhere in our fight against AGW or a whole host of other environmental and health issues. Yes I said health too, because those health outcomes you mentioned all used industrialised meat in their studies. Properly raised food on the land, including animals, have never been shown to be unhealthy, quite the contrary. Greener Pastures: How grass-fed beef and dairy contribute to healthy eating

Learn more about it here Welcome to the Future of Agriculture

Reducing meat production in the industrialized system will have little to no effect on rainforest deforestation, because other industrialized uses for that overproduction will instantly take up any gains made there. This so called "solution" is a false hope. It does not adress the main problem, which the Father of Organic agriculture Sir Albert Howard correctly foresaw so many years ago.