The glass, aluminum, and stainless steel panels reclined at low angles and basked in the sun as the men in suits and ties, flanked by reporters, took to the West Wing roof to look at what they thought was the future. That day, June 20, 1979, was clear enough for the sun to bring out a bright reflection on the panels, and for shadows of those on the roof to be drawn dark and tight around them.

For President Jimmy Carter, it had been nearly three years of tough fighting for clean energy. After a long rollout of green tax credits, the creation of a nascent Energy Department, and a pledge to conduct the “moral equivalent of war” (at the time, spoofed by critics as “MEOW”) against an energy crisis, Carter had built up scars. And there would be more to come. He had had battles with Congress and with his political enemies over green issues. But he had some victories, too, and this day brought one more, a small moment of symbolism.

Solar panels, some 32 of them, were on the roof of the White House. The set was just right — the sun had come out for the press as though for a stage call. Tape rolled, the cameras snapped.

Self-conscious about his idealism, or perhaps just realistic, the president gave voice to his doubts about the panels: “A generation from now, this solar heater can either be a curiosity, a museum piece, an example of a road not taken, or it can be a small part of one of the greatest and most exciting adventures ever undertaken by the American people.”

The point of all this was simple, Carter said. America was to harness “the power of the sun to enrich our lives as we move away from our crippling dependence on foreign oil.”

Carter was a person of simplicity, of conservation; he was also sort of an oddball, a hybrid, an anti-political Christian proto-green who had donned a cardigan sweater, lowered the White House thermostat, and declared “Sun Day” on May 3, 1978.

A year later he had his panels.

Sabin 33 #9 - Will reliance on solar make the United States dependent on China and other countries?

Posted on 31 December 2024 by BaerbelW

On November 1, 2024 we announced the publication of 33 rebuttals based on the report "Rebutting 33 False Claims About Solar, Wind, and Electric Vehicles" written by Matthew Eisenson, Jacob Elkin, Andy Fitch, Matthew Ard, Kaya Sittinger & Samuel Lavine and published by the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia Law School in 2024. Below is the blog post version of rebuttal #9 based on Sabin's report.

Although the United States still imports a majority of the solar panels it installs, domestic solar manufacturing is on the rise, especially following passage of the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), and the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act (IRA)1. In 2022, the United States manufactured approximately 10% more solar panels than in 20212. This share is likely to grow as manufacturers take advantage of IIJA and IRA incentives to open factories in the United States3. In addition, as previously noted, roughly 65% of today’s U.S. solar production jobs are in project development and 6% are in operations or maintenance, most of which cannot be outsourced4.

Finally, to the extent that there are concerns that solar energy will increase the United States’ dependence on China specifically, it bears noting that China is no longer a major source of solar panel imports—at least not directly5. Tariffs imposed by the U.S. government in 2012 on Chinese-sourced solar panels have considerably diminished China’s status as a principal U.S. supplier. In 2022, approximately 77% of U.S. solar panel imports came from four countries: Vietnam (37%), Thailand (17%), Malaysia (16%) and Cambodia (7%). While the U.S. Department of Commerce found that companies in these four countries have been incorporating Chinese-sourced materials without paying corresponding tariffs, the U.S. Government has taken measures to crack down on noncompliance6. In particular, the U.S. Government now requires, as of June 2024, that solar manufacturers exporting from these countries to the U.S. certify their compliance with all relevant trade rules, subject to potential audit7.

2024 in review - a bittersweet year for our team

Posted on 30 December 2024 by BaerbelW

The year 2024 at Skeptical Science has been bittersweet. We are incredibly proud of the progress we've made in debunking climate myths, thanks in large part to the tireless efforts of our late colleague John Mason. John passed away unexpectedly in September, leaving a huge void in our team. This post is a tribute to his immense contributions and the lasting impact he'll have on climate science education for years to come.

As in previous recaps, this one is divided into several sections:

|

2024 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming News Roundup #52

Posted on 29 December 2024 by BaerbelW, Doug Bostrom

This week's roundup is the second one published soleley by category. We are still interested in feedback to hone the categorization, so if you spot any clear misses and/or have suggestions for additional categories, please let us know in the comments. Thanks!

Stories we promoted this week, by category:

Climate Change Impacts

- Climate change could create millions of climate migrants by 2050 Droughts, floods, sea level rise, and other climate change impacts are uprooting people from their homes. by YCC Team, Yale Climate Connections, Dec 26, 2024

- 2024: A year of extreme heat and growing climate danger This year is set to be the hottest on record – but scientists say there’s still time to limit temperature rise and harm from climate impacts by Megan Rowling, Climate Home News, Dec 27, 2024

- When Risks Become Reality: Extreme Weather In 2024 When Risks Become Reality: Extreme Weather in 2024 is our annual report, published this year for the first time. by WWA-Team, World Weather Attribution, Dec 27, 2024

- California's piers may not be able to withstand climate change by Noah Haggerty, Climate , Dec 28, 2024

Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation

- Uruguay, pioneer in renewable energy: a model for the world? The country is a global leader in the transition toward green energy, following a radical transformation of its energy mix. by Johani Carolina Ponce, Yale Climate Connections, Dec 18, 2024

Climate education and communication

- How to teach climate change so 15-year-olds can act OECD’s Pisa program will measure the ability of students to take action in response to climate anxiety and ‘take their position and role in the global world’ by Petra Stock, The Guardian, Dec 23, 2024

- Is silence golden? What a change expert says about family climate conversations at Christmas time Do you engage with climate deniers that come your way this Christmas? And if so, what’s the best way to do it? by Jen Marsden, Euro News, Dec 22, 2024

Skeptical Science New Research for Week #52 2024

Posted on 26 December 2024 by Doug Bostrom, Marc Kodack

Open access notables

Trends in Oceanic Precipitation Characteristics Inferred From Shipboard Present-Weather Reports, 1950–2019, Tran & Petty, Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres:

Although ship reports are susceptible to subjective interpretation, the inferred distributions of these phenomena are consistent with observations from other platforms such as satellites and coastal surface stations. These distributions highlight widespread 70-year trends that are often consistent across both annual and seasonal frequencies, with statistical significance at 95% confidence. The relative frequency of ship-reported drizzle has largely increased in the tropics annually and seasonally, with linear best-fit relative increases by as much as 15% per decade. Decreased relative frequencies have been observed in parts of the subtropics and at higher latitudes. Heavier precipitation has encompassed a growing fraction of non-drizzle precipitation reports over the subtropical North Pacific and Mediterranean. The relative frequency of thunderstorm reports has declined over the open Atlantic but show positive trends over the Mediterranean and the western Atlantic. The trends in relative frozen precipitation occurrence suggest a poleward retreat of areas receiving frozen precipitation in the Northern Hemisphere. Possible mechanisms for these ship-observed trends are discussed and placed in the context of the modeled effects of climate change on global precipitation.

Increase Asymmetric Warming Rates Between Daytime and Nighttime Temperatures Over Global Land During Recent Decades, Liu et al., Geophysical Research Letters:

Global climate change is causing uneven warming patterns, which significantly affect how ecosystems exchange water and carbon. One important way to understand this is through the diurnal temperature range (DTR), which measures the difference between daytime and nighttime temperatures. In this study, we examined DTR changes globally from 1961 to 2022 using a method called ensemble empirical mode decomposition (EEMD). We discovered that the overall trend in DTR reversed around 1988, changing from a decline to an increase, which affected nearly half of the world's land areas. Subsequent to the reversal, the most pronounced increases were observed in temperate regions, whereas tropical areas exhibited a more subdued rate of rise. Interestingly, we found that the rate of increase in DTR is stronger in southern latitudes compared to northern latitudes.

Near-term carbon dioxide removal deployment can minimize disruptive pace of decarbonization and economic risks towards United States’ net-zero goal, Adun et al., Communications Earth & Environment:

Deep decarbonization is essential for achieving the Paris Agreement goals, and carbon dioxide removal is required to address residual emissions and achieve net-zero targets. However, the implications of delaying the deployment of removal technologies remain unclear. We quantify how different carbon removal methods and their deployment timing affect achieving net zero emissions by 2050 in the United States. Our findings show that postponing novel technologies until mid-century forces accelerated decarbonization of energy-intensive sectors, reducing residual emissions by at least 12% compared with near-term deployment of carbon dioxide removal. This delay increases transition costs, requiring carbon prices 59–79% higher than with near-term deployment. It also heightens the risk of premature fossil fuel retirement in the electricity sector, leading to 128–220 billion USD losses compared to gradual scale up starting now. A balanced, near-term co-deployment of novel removal methods mitigates risks associated with relying on a single approach and addresses sustainability and scalability concerns.

A New Heat Stress Index for Climate Change Assessment, Lanzante, Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society:

The heat index (HI), based on Steadman’s model of thermoregulation, estimates heat stress on the human body from ambient temperature and humidity. It has been used widely both in applications, such as the issuance of heat advisories by the National Weather Service (NWS) and for research on possible changes in the future due to climate change. However, temperature/humidity combinations that exceed the applicable range of the model are becoming more common due to climate warming. Recent work by Lu and Romps has produced an extended heat index (EHI), which is valid for values outside the range of the original HI. For these values, the HI can underestimate the EHI by a considerable amount. This work utilizes observed data from 15 U.S. weather stations along with bias-adjusted output from a climate model to explore the spatial and temporal aspects of the disparity between the HI and the EHI from the recent past out to the end of the twenty-first century. The underestimate of human heat stress by the HI is found to be the largest for the most extreme cases (5°–10°C), which are also the most impactful. Conditions warranting NWS excessive heat warnings are found to increase dramatically from less than 5% of days historically at most stations to more than 90% in the future at some stations.

Climate extremes and risks: links between climate science and decision-making, Sillmann et al., Frontiers in Climate

The World Climate Research Programme (WCRP) envisions a future where actionable climate information is universally accessible, supporting decision makers in preparing for and responding to climate change. In this perspective, we advocate for enhancing links between climate science and decision-making through a better and more decision-relevant understanding of climate impacts. The proposed framework comprises three pillars: climate science, impact science, and decision-making, focusing on generating seamless climate information from sub-seasonal, seasonal, decadal to century timescales informed by observed climate events and their impacts.

From this weeks government/NGO section:

Balancing Act. Assessing Risks and Governance of Climate Intervention, Porambo et al., Applied Physics Laboratory, Johns Hopkins University

Nations, organizations, and individuals may soon look to climate intervention, also known as geoengineering, as a means to avoid the most severe effects of climate change. Despite the hope that climate intervention may prevent the increasingly dire climate change projections from becoming reality, the efficacy of many climate intervention methods remains uncertain. Moreover, many methods pose their own risks to the environment, global ecosystems, and critical human systems. These uncertainties and risks, when combined with the relatively few barriers to unilateral deployment for many methods, drive the need for national and international regulation of climate intervention research, testing, development, and deployment. The authors summarize the effects of two controversial climate intervention methods—stratospheric aerosol injection and ocean iron fertilization—on national security, considering their abilities to both stop and reverse the effects of climate change and the possible direct, unintended environmental changes. It then examines governance principles for climate intervention from a combined national security and technical perspective, deriving principles for addressing climate intervention research, governance, and possible use and making recommendations for the path forward.

Producer perceptions of environmental sustainability and climate change. 2024 national poll of farmers and ranchers, Leger, Farmers for Climate Solutions

When farmers and ranchers were asked an open-ended question—at the very beginning of the poll—about the top challenge for the agricultural sector for the next decade, climate change was the number one answer. 76% of farmers and ranchers report being impacted by severe weather in the past five years. Producers are worried that climate change will bring more restrictive policies and regulations, reduce income and yields, and negatively affect their mental health. 87% of farmers and ranchers consider themselves good stewards of the land, and 47% feel they can do more to improve environmental outcomes in their operations. Producers want a range of supports to adopt high resilience, low emissions practices, including technical support and training, financial incentives, risk management tools, and price premiums for sustainable products.

139 articles in 52 journals by 858 contributing authors

Physical science of climate change, effects

Estimated human-induced warming from a linear temperature and atmospheric CO2 relationship, Jarvis & Forster, Nature Geoscience Open Access 10.1038/s41561-024-01580-5

Impact of Canadian wildfires on aerosol and ice clouds in the early-autumn Arctic, Sato et al., Atmospheric Research Open Access 10.1016/j.atmosres.2024.107893

Irreversible changes in the sea surface temperature threshold for tropical convection to CO2 forcing, Park et al., Communications Earth & Environment Open Access 10.1038/s43247-024-01751-7

Climate Adam: 2024 Through the Eyes of a Climate Scientist

Posted on 25 December 2024 by Guest Author

This video includes personal musings and conclusions of the creator climate scientist Dr. Adam Levy. It is presented to our readers as an informed perspective. Please see video description for references (if any).

2024 has been a series of bad news for climate change. From scorching global temperatures leading to devastating extreme weather, to the rise of climate denying politicians and directionless negotiations. As global warming approaches 1.5 degrees, I thought it was vital to break down how this year has affected me - a climate scientist working on the topic for over a decade. So I'm sharing some of the lessons I've learned, and why the last thing we should be doing right now is despairing.

Support ClimateAdam on patreon: https://patreon.com/climateadam

Sabin 33 #8 - Will solar development destroy jobs?

Posted on 24 December 2024 by BaerbelW

On November 1, 2024 we announced the publication of 33 rebuttals based on the report "Rebutting 33 False Claims About Solar, Wind, and Electric Vehicles" written by Matthew Eisenson, Jacob Elkin, Andy Fitch, Matthew Ard, Kaya Sittinger & Samuel Lavine and published by the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia Law School in 2024. Below is the blog post version of rebuttal #8 based on Sabin's report.

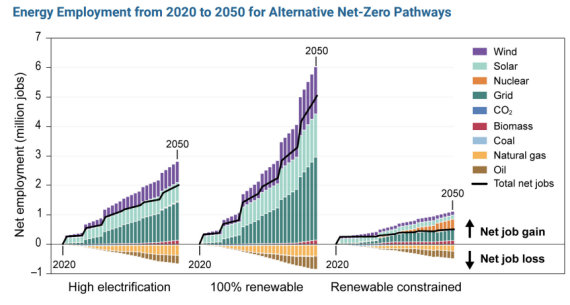

Solar development creates significantly more jobs per unit of energy generated than other types of energy production, including natural gas1. Moreover, the number of jobs created by the renewable energy industry, including solar, is expected to far exceed the number lost due to a shift away from fossil fuels. The United States’ Fifth National Climate Assessment predicts that there will be nearly 3,000,000 new solar, wind, and transmission-related jobs by 2050 in a high electrification scenario and 6,000,000 new jobs in a 100% renewable scenario, with less than 1,000,000 fossil fuel-related jobs lost2.

Figure 1: Energy employment from 2020 to 2050 under various U.S. net-zero GHG emissions scenarios. Source: U.S. Global Change Research Program.

As of 2022, the solar industry supported approximately 346,143 U.S. jobs, including 175,302 construction jobs and 44,875 manufacturing jobs, with numbers generally increasing each year3. In addition, most of these jobs cannot be outsourced. Roughly 65% of today’s U.S. solar energy jobs are in project development and 6% are in operations or maintenance, most of which cannot be exported4. The number of jobs in solar energy also exceeds those in the fossil fuel generation industries. In Kentucky, for example, there are now eight times as many jobs in clean energy, including solar, as coal mining5. Throughout the United States, there are roughly 5.4 times as many jobs in solar alone than in coal, and there are roughly 1.78 times as many jobs in solar than in coal, gas, and oil generation combined.

Domestic job growth in solar production and related industries has been further accelerated by recent federal legislation, including the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, and the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act, which collectively provide more than $60 billion to support clean energy manufacturing, primarily with domestic supply chains6. In response, manufacturers have announced plans to build multibillion dollar solar panel manufacturing facilities and related battery manufacturing facilities in the United States that will employ thousands of workers7. At a smaller scale, the emerging solar recycling industry has also begun to create jobs8.

Uruguay, pioneer in renewable energy: a model for the world?

Posted on 23 December 2024 by Guest Author

This is a re-post from Yale Climate Connections by Johani Carolina Ponce

Tacuarembó, Uruguay. (Image credit: Getty Images)

Tacuarembó, Uruguay. (Image credit: Getty Images)

[Haz clic aquí para leer en español]

It has a population of just under 3.5 million inhabitants, produces nearly 550,000 tons of beef per year, and boasts a glorious soccer reputation with two World Cups in its history and a present full of world-class stars. Uruguay, the country of writer Mario Benedetti and soccer player Luis Suárez, has achieved what many countries have pledged for decades: 98% of its grid runs on green energy.

Luis Prats, 62, is a Uruguayan journalist and contributor to the Montevideo newspaper El País. He remembers that during his childhood, blackouts were common in Uruguay because there were major problems with energy generation.

“At that time, more than 50 years ago, electricity came from two small dams and from generation in a thermal plant,” Prats explained in Spanish by telephone. “If there was a drought in the Negro River basin, where those dams are, there were already cuts and sometimes restrictions on the use of electrical energy.”

Just 17 years ago, Uruguay used fossil fuels for a third of its energy generation, according to the World Resources Institute.

Today, only 2% of the electricity consumed in Uruguay is generated from fossil sources. The country’s thermal power plants rarely need to be activated, except when natural resources are insufficient.

Half of Uruguay’s electricity is generated in the country’s dams, and 10% percent comes from agricultural and industrial waste and the sun. But wind, at 38%, is the main protagonist of the revolution in the electrical grid. But how did the country achieve it? Who were the architects of this energy transition?

2024 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming News Roundup #51

Posted on 22 December 2024 by BaerbelW, Doug Bostrom, John Hartz

Based on feedback we received, this week's roundup is the first one published soleley by category. We are still interested in feedback to hone the categorization, so if you spot any clear misses and/or have suggestions for additional categories, please let us know in the comments. Thanks!

Stories we promoted this week, by category:

Climate Change Impacts

- How much should you worry about a collapse of the Atlantic conveyor belt? Scientists warned recently that the risk “has so far been greatly underestimated.” by Bob Henson, Yale Climate Connections, Dec 11, 2024

- Shrinking wings, bigger beaks: Birds are reshaping themselves in a warming world by Sara Ryding, Alexandra McQueen and Matthew Symonds, Phys.org - reposted from The Conversation, Dec 16, 2024

- New data shows just how bad the climate insurance crisis has become Two congressional reports make clear that, with increasingly frequent hurricanes, floods, and fires, "the model of insurance as it stands right now isn't working." by Tik Root, Grist, Dec 19, 2024

Climate Law and Justice

- New Report Shows a Surge in European SLAPP Suits as Fossil Fuel Industry Works to Obstruct Climate Action But experts say these “abusive” lawsuits, which are designed to demoralize and drain resources from activists, should be fought, not feared. by Stella Levantesi, DeSmog, Dec 17, 2024

- Montana top court upholds landmark youth climate ruling Montana's Supreme Court upholds a lower court's decision siding with 16 youngsters arguing that the state violated their right to a clean environment. by Max Matza, BBC News, Dec 19, 2024

- Montana Supreme Court backs youth plaintiffs in groundbreaking climate trial by Ellis Juhlin, NPR - Montana Public Radio, Dec 18, 2024

Climate Policy and Politics

- Anxious scientists brace for Trump`s climate denialism: `We have a target on our backs` Experts express fear – and resilience – as they prepare for president-elect’s potential attacks on climate research by Oliver Milman, The Guardian, Dec 15, 2024

- 6 Fracking Billionaires and Climate Denial Groups Behind Trump`s Cabinet Trump’s nominees are backed by major players in the world of climate obstruction – from Project 2025 and Koch network fixtures to oil-soaked Christian nationalists. by Joe Fassler, DeSmog, Dec 16, 2024

- A new podcast explores the `hot mess` of climate politics Podcast from Citizen's Climate Lobby talks about how the world of climate facts bridges political divides. by Flannery Winchester, Citizens' Climate Lobby, Dec 18, 2024

- Tim Ryan is a paid fossil fuel mouthpiece Creating an atmosphere of confusion is a well-rewarded job of work, according to this article. by Emily Atkin, HEATED, Dec 12, 2024

- Carbon tax had 'negligible' impact on inflation, new study says University of Calgary professors find that prices are only 0.5% higher due to carbon tax and other measures by Peter Zimonjic, Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, Dec 12, 2024

- Nigel Farage Helps to Launch U.S. Climate Denial Group in UK The Heartland Institute, which questions human-made climate change, has established a new branch in London by Sam Bright, DeSmog, Dec 19, 2024

Fact brief - Are we heading into an 'ice age'?

Posted on 21 December 2024 by Guest Author

![]() Skeptical Science is partnering with Gigafact to produce fact briefs — bite-sized fact checks of trending claims. This fact brief was written by Sue Bin Park from the Gigafact team in collaboration with members from our team. You can submit claims you think need checking via the tipline.

Skeptical Science is partnering with Gigafact to produce fact briefs — bite-sized fact checks of trending claims. This fact brief was written by Sue Bin Park from the Gigafact team in collaboration with members from our team. You can submit claims you think need checking via the tipline.

Note: Technically we are currently in an ice age (there is ice at the poles) and what we're really discussing here is the glacial cycle. We are in an inter-glacial and the question is if we could be heading for another glacial period. However, since the myth typically refers to this as an "ice age", we decided to stick with that term.

Are we heading into an ‘ice age’?

The planet has been getting warmer since the Industrial Revolution, not colder.

The planet has been getting warmer since the Industrial Revolution, not colder.

Historically, ice ages have followed changes in the Earth’s relationship to the sun. Natural cycles affect the tilt of Earth’s axis and its orbit around the sun. As Earth’s axis becomes less tilted, and its orbit more elliptical, it receives less solar radiation.

These “Milankovitch” cycles occur over thousands of years. Currently, Earth’s tilt is halfway between its maximum and minimum while its orbit is nearly circular.

In the absence of human activity, Earth may have gradually cooled in the coming centuries with phases corresponding to a decreasing tilt and an increasing orbital eccentricity.

However, fossil-fuel burning and other actions have raised CO2 levels to 420 parts per million—far above the 180-280 ppm seen during past ice ages. This extra CO2 has made it harder for heat to escape the atmosphere, overpowering the natural cooling trend.

Go to full rebuttal on Skeptical Science or to the fact brief on Gigafact

This fact brief is responsive to conversations such as this one.

Sources

NASA Milankovitch (Orbital) Cycles and Their Role in Earth’s Climate

Cornell University Understanding long-term climate and CO2 change

UC San Diego The Keeling Curve Hits 420 PPM

Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Are we heading toward another Little Ice Age?

NASA Global Temperature

Skeptical Science New Research for Week #51 2024

Posted on 19 December 2024 by Doug Bostrom, Marc Kodack

Open access notables

An intensification of surface Earth’s energy imbalance since the late 20th century, Li et al., Communications Earth & Environment:

Tracking the energy balance of the Earth system is a key method for studying the contribution of human activities to climate change. However, accurately estimating the surface energy balance has long been a challenge, primarily due to uncertainties that dwarf the energy flux changes induced and a lack of precise observational data at the surface. We have employed the Bayesian Model Averaging (BMA) method, integrating it with recent developments in surface solar radiation observational data, to refine the ensemble of CMIP6 model outputs. This has resulted in an enhanced estimation of Surface Earth System Energy Imbalance (EEI) changes since the late 19th century. Our findings show that CMIP6 model outputs, constrained by this observational data, reflect changes in energy imbalance consistent with observations in Ocean Heat Content (OHC), offering a narrower uncertainty range at the 95% confidence level than previous estimates. Observing the EEI series, dominated by changes due to external forcing, we note a relative stability (0.22 Wm−2) over the past half-century, but with a intensification (reaching 0.80 Wm−2) in the mid to late 1990s, indicating an escalation in the adverse impacts of global warming and climate change, which provides another independent confirmation of what recent studies have shown.

Fusion of Probabilistic Projections of Sea-Level Rise, Grandey et al., Earth's Future:

A probabilistic projection of sea-level rise uses a probability distribution to represent scientific uncertainty. However, alternative probabilistic projections of sea-level rise differ markedly, revealing ambiguity, which poses a challenge to scientific assessment and decision-making. To address the challenge of ambiguity, we propose a new approach to quantify a best estimate of the scientific uncertainty associated with sea-level rise. Our proposed fusion combines the complementary strengths of the ice sheet models and expert elicitations that were used in the Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Under a low-emissions scenario, the fusion's very likely range (5th–95th percentiles) of global mean sea-level rise is 0.3–1.0 m by 2100. Under a high-emissions scenario, the very likely range is 0.5–1.9 m. The 95th percentile projection of 1.9 m can inform a high-end storyline, supporting decision-making for activities with low uncertainty tolerance. By quantifying a best estimate of scientific uncertainty, the fusion caters to diverse users.

Earth's Climate History Explains Life's Temperature Optima, Schipper et al., Ecology and Evolution:

Why does the growth of most life forms exhibit a narrow range of optimal temperatures below 40°C? We hypothesize that the recently identified stable range of oceanic temperatures of ~5 to 37°C for more than two billion years of Earth history tightly constrained the evolution of prokaryotic thermal performance curves to optimal temperatures for growth to less than 40°C. We tested whether competitive mechanisms reproduced the observed upper limits of life's temperature optima using simple Lotka–Volterra models of interspecific competition between organisms with different temperature optima. Model results supported our proposition whereby organisms with temperature optima up to 37°C were most competitive. Model results were highly robust to a wide range of reasonable variations in temperature response curves of modeled species. We further propose that inheritance of prokaryotic genes and subsequent co-evolution with microbial partners may have resulted in eukaryotes also fixing their temperature optima within this narrow temperature range. We hope this hypothesis will motivate considerable discussion and future work to advance our understanding of the remarkable consistency of the temperature dependence of life.

Widespread outdoor exposure to uncompensable heat stress with warming, Fan & McColl, Communications Earth & Environment:

Previous studies projected an increasing risk of uncompensable heat stress indoors in a warming climate. However, little is known about the timing and extent of this risk for those engaged in essential outdoor activities, such as water collection and farming. Here, we employ a physically-based human energy balance model, which considers radiative, wind, and key physiological effects, to project global risk of uncompensable heat stress outdoors using bias-corrected climate model outputs. Focusing on farmers (approximately 850 million people), our model shows that an ensemble median 2.8% (15%) would be subject to several days of uncompensable heat stress yearly at 2 (4) °C of warming relative to preindustrial. Focusing on people who must walk outside to access drinking water (approximately 700 million people), 3.4% (23%) would be impacted at 2 (4) °C of warming. Outdoor work would need to be completed at night or in the early morning during these events.

["uncompensable" means physiologically intolerable, acutely dangerous, ultimately deadly]

Stabilising CO2 concentration as a channel for global disaster risk mitigation, Lu & Tambakis, Scientific Report:

We investigate the influence of anthropogenic CO2 concentration fluctuations on the likelihood of climate-related disasters. We calibrate annual incidence rates against global disasters and CO2 growth spanning from 1960 to 2022 based on a dynamic panel logit model. We also study the sensitivity of disaster incidence to stochastic carbon dynamics consistent with IPCC-projected climate outcomes for 2100. The key insight is that present and lagged CO2 growth contains valuable information about the likelihood of future disaster events. We further show that lowering carbon stock uncertainty by dampening the persistence or the variability of CO2 concentration has a first-order impact on mitigating expected disaster risk.

Fact-checking information from large language models can decrease headline discernment, DeVerna et al., Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences:

This study explores how large language models (LLMs) used for fact-checking affect the perception and dissemination of political news headlines. Despite the growing adoption of AI and tests of its ability to counter online misinformation, little is known about how people respond to LLM-driven fact-checking. This experiment reveals that even LLMs that accurately identify false headlines do not necessarily enhance users’ abilities to discern headline accuracy or promote accurate news sharing. LLM fact checks can actually reduce belief in true news wrongly labeled as false and increase belief in dubious headlines when the AI is unsure about an article’s veracity. These findings underscore the need for research on AI fact-checking’s unintended consequences, informing policies to enhance information integrity in the digital age.

Droughts in Wind and Solar Power: Assessing Climate Model Simulations for a Net-Zero Energy Future, Liu et al., Geophysical Research Letters:

Understanding and predicting “droughts” in wind and solar power availability can help the electric grid operator planning and operation toward deep renewable penetration. We assess climate models' ability to simulate these droughts at different horizontal resolutions, ∼100 and ∼25 km, over Western North America and Texas. We find that these power droughts are associated with the high/low pressure systems. The simulated wind and solar power variabilities and their corresponding droughts during historical periods are more sensitive to the model bias than to the model resolution. Future climate simulations reveal varied future change of these droughts across different regions. Although model resolution does not affect the simulation of historical droughts, it does impact the simulated future changes. This suggests that regional response to future warming can vary considerably in high- and low-resolution models. These insights have important implications for adapting power system planning and operations to the changing climate.

From this week's government/NGO section:

How global warming beliefs differ by education levels in India, Morris et al., Yale Program on Climate Change Communication

Given India’s diverse population, it is likely that global warming beliefs vary across different subgroups of the population. Given the large differences in levels of educational attainment in India, education might be an especially important factor in Indians’ global warming beliefs and attitudes. Further, understanding the role of education in public responses to climate change can help inform the design of communication strategies for these different subgroups. There were large differences in global warming awareness. For people who are not literate, 56% say they have never heard of global warming while, for people with a college degree or higher, only 7% say the same. Global warming awareness increases as educational level increases.

U.S. Climate Pathways for 2035 with Strong Non-Federal Leadership, Zhao et al., Center for Global Sustainability, University of Maryland

The authors assess U.S. climate pathways for 2035 across a range of federal climate ambitions with continued and enhanced non-federal climate action. The authors find that in the event of the reversal of strong federal climate action, enhanced non-federal action alone could still significantly bolster the transition to clean energy. With actions including the widespread adoption of renewable and clean electricity targets, California’s EV sales targets, vehicle miles traveled reduction policies, building efficiency, and electrification standards, industry carbon capture and sequestration targets, oil and gas methane intensity standards, and increased waste diversion efforts, the United States could achieve 54-62% emissions reductions by 2035, even in the context of federal inactions or rollbacks.

Voters Support Phasing Out Fossil Fuel Extraction, Caggiano et al., Climate and Community Institute

While the United States has made progress towards a buildout of clean and renewable energy, there has been very little serious discussion of curtailing fossil fuel extraction. Though many politicians believe that halting existing or new fossil fuel production is politically unpopular, there is surprisingly limited data to back this claim. To better understand how the general public views policies aimed at phasing out fossil fuel production, we conducted a nationally representative survey. Overall, the results demonstrate widespread support for policies to curtail the extraction of fossil fuels.

135 articles in 62 journals by 878 contributing authors

Physical science of climate change, effects

Acceleration of Warming, Deoxygenation, and Acidification in the Arabian Gulf Driven by Weakening of Summer Winds, Lachkar et al., Geophysical Research Letters Open Access 10.1029/2024gl109898

Basic Physics Predicts Stronger High Cloud Radiative Heating With Warming, Gasparini et al., Geophysical Research Letters Open Access pdf 10.1029/2024gl111228

Stop emissions, stop warming: A climate reality check

Posted on 18 December 2024 by Guest Author

This is a re-post from The Climate Brink by Andrew Dessler

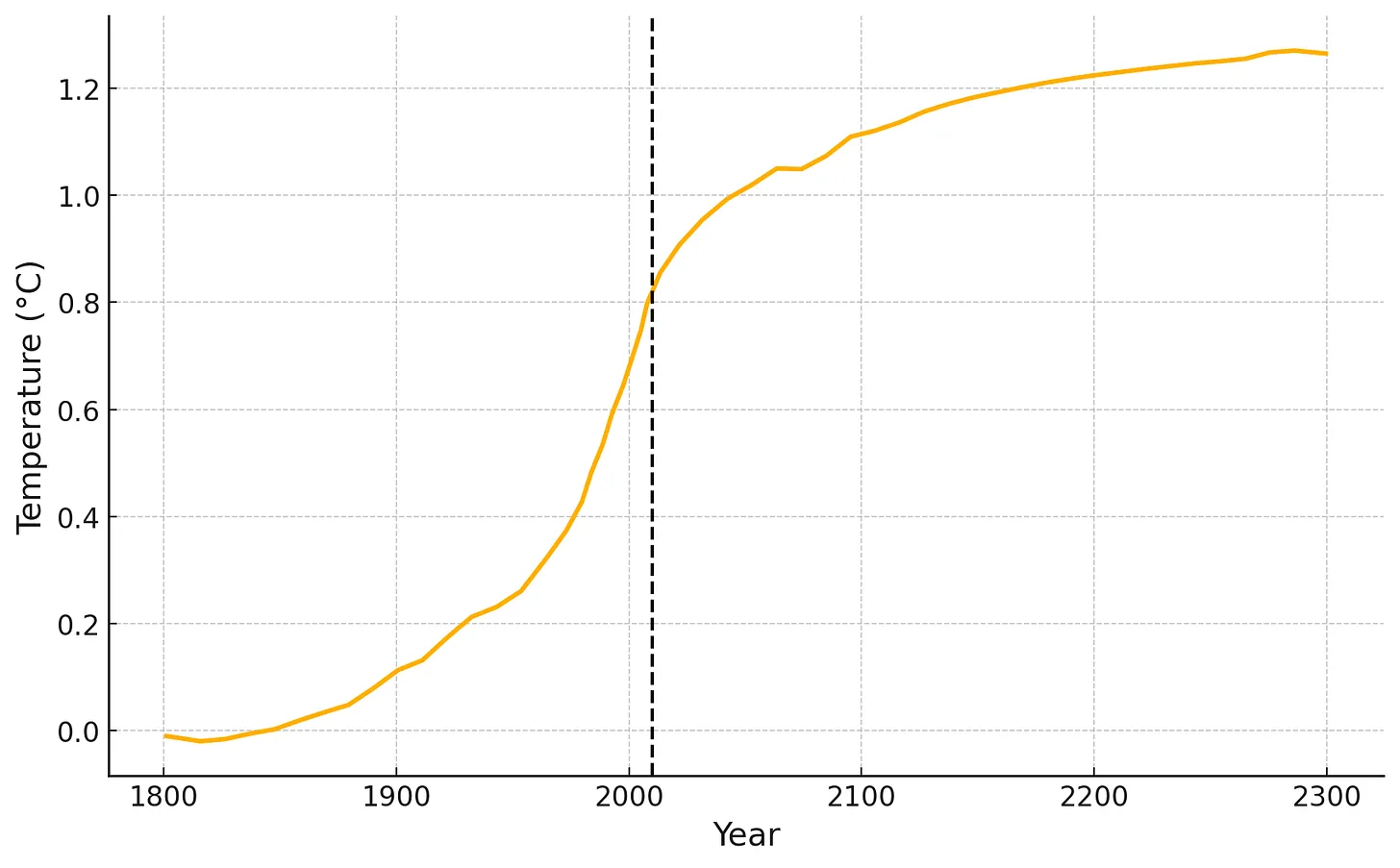

One of the most important concepts in climate science is the idea of committed warming — how much future warming is coming from carbon dioxide that we’ve already emitted.

Understanding the extent of committed warming is vital because it informs our current climate situation. If there is a significant amount of committed warming already “locked in,” then we have much less ability to avoid the levels of warming that policymakers judge as dangerous.

In a previous post about what made me optimistic about the climate problem, I wrote:

When humans stop emitting greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, the climate will stop warming.

I received emails and comments from people who found that difficult to believe, so I thought I’d write a post about why this is true and shed light on the reasons behind the controversy surrounding it.

the 2000s

To understand why people are so confused about this, let’s step back to the 2000s. In the IPCC’s fourth assessment report (published in 2007), committed warming was defined to be:

If the concentrations of greenhouse gases and aerosols were held fixed after a period of change, the climate system would continue to respond due to the thermal inertia of the oceans and ice sheets and their long time scales for adjustment. ‘Committed warming’ is defined here as the further change in global mean temperature after atmospheric composition, and hence radiative forcing, is held constant. (from box TS.9)

Consider this simple example: humans emit CO2 until the year 2010, when the atmospheric concentration of CO2 reaches 400 ppm. After that point, the concentration of CO2 is held fixed at 400 ppm in perpetuity, as are all other components of the atmosphere (methane, aerosols, etc.).

In this scenario, maintaining a fixed atmospheric composition is analogous to setting a thermostat at a constant set point for the Earth's climate system. This is the resulting trajectory:

As you can see, the climate continues to warm well after concentrations are fixed (the vertical dashed line). The reason is the immense thermal inertia of the ocean. In much the same way that it takes a very long time for a hot tub filled with cold water to warm after you set the heater, the oceans will take a very very long time to fully warm to reach equilibrium with the fixed atmospheric composition.

Sabin 33 #7 - Are solar projects hurting farmers and rural communities?

Posted on 17 December 2024 by BaerbelW

On November 1, 2024 we announced the publication of 33 rebuttals based on the report "Rebutting 33 False Claims About Solar, Wind, and Electric Vehicles" written by Matthew Eisenson, Jacob Elkin, Andy Fitch, Matthew Ard, Kaya Sittinger & Samuel Lavine and published by the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia Law School in 2024. Below is the blog post version of rebuttal #7 based on Sabin's report.

Ambitious solar deployment would utilize a relatively small percentage of U.S. land when compared to the land currently being used for agriculture. The Department of Energy estimated that total U.S. solar development would take up roughly 10.3 million acres in a scenario in which cumulative solar deployment reaches 1,050–1,570 GW by 2050, the highest land-use scenario that DOE assessed in its 2021 Solar Futures Study1. If all 10.3 million acres of solar farms were sited on farmland, they would occupy only 1.15% of the 895,300,000 acres of U.S. farmland as of 20212. However, many of these projects will not be located on farmland.

Furthermore, solar arrays can be designed to allow, and even enhance, continued agricultural production on site. This practice, known as agrivoltaics, provides numerous benefits to farmers and rural communities, especially in hot or dry climates3. Agrivoltaics allow farmers to grow crops and even to graze livestock such as sheep beneath or between rows of solar panels4 (also Adeh et al. 2019). When mounted above crops and vegetation, solar panels can provide beneficial shade during the day (Williams et al. 2023). Multiple studies have shown that these conditions can enhance a farm’s productivity and efficiency (Aroca-Delgado et al. 2018). One study found, for example, that "lettuces can maintain relatively high yields under PV" because of their capacity to calibrate "leaf area to light availability" (Marrou et al. 2013). Extra shading from solar panels also reduces evaporation, thereby reducing water usage for crops by around 14-29%, depending on the level of shade (Dinesh & Pearce 2016). Reduced evaporation from solar installations can likewise mitigate soil erosion. Solar farms can also create refuge habitats for endangered pollinator species, further boosting crop yields while supporting native wild species5. Overall, agrivoltaics can increase the economic value of the average farm by over 30%, while increasing annual income by about 8%. Farmers in other countries have begun implementing agrivoltaic systems (Tajima & Iida 2021). As of March 2019, Japan had 1,992 agrivoltaic farms, growing over 120 different crops while simultaneously generating 500,000 to 600,000 MWh of energy6.

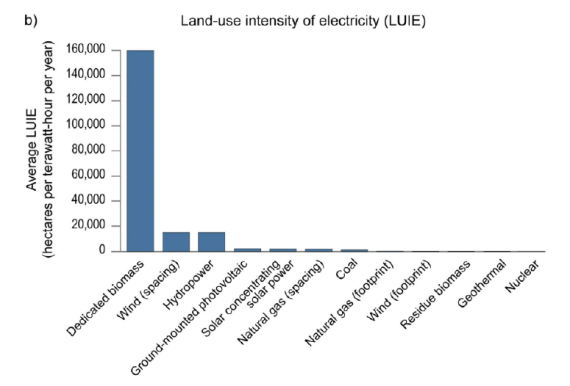

Furthermore, the argument that solar development will imperil the food supply is belied by the fact that tens of millions of acres of farmland are currently being used to grow crops for other purposes, such as the production of corn ethanol. Currently, roughly 90 million acres of agricultural land in the United States is dedicated to corn, with nearly 45% of that corn being used for ethanol production7. Solar energy could provide a significantly more efficient use of the same land. Corn-derived ethanol used to power internal combustion engines has been calculated to require between 63 and 197 times more land than solar PV powering electric vehicles to achieve the same number of transportation miles8. If converted to electricity to power electric vehicles, ethanol would still need roughly 32 times more land than solar PV to achieve the same number of transportation miles. And even when accounting for other energy by-products of ethanol production, solar PV produces between 14 and 17 times more gross energy per acre than corn. The figure below contrasts the land use requirements of solar PV with dedicated biomass and other energy sources. Whereas dedicated biomass consumes an average of 160,000 hectares of land per terawatt-hour per year, ground-mounted solar PV consumes an average of 2,100 (Lovering et al. 2022).

Figure 4: Average land-use intensity of electricity, measured in hectares per terawatt-hour per year. Source: U.S. Global Change Research Program (visualizing data from Jessica Lovering et al. 2022).

Finally, while solar installations, like any infrastructure projects, will inevitably have some adverse impacts, the failure to build the infrastructure necessary to avoid climate change poses a far more severe threat to agricultural production. Climate change already harms food production across the country and globe through extreme weather events, weather instability, and water scarcity9. The most recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report forecasts that climate change will cause up to 80 million additional people to be at risk of hunger by 205010. A 2019 IPCC report forecasted up to 29% price increases for cereal grains by 2050 due to climate change11. These price increases would strain consumers globally, while also producing uneven regional effects. Moreover, while higher carbon dioxide levels may initially increase yield for certain crops at lower temperature increases, these crops will likely provide lower nutritional quality. For example, wheat grown at 546–586 parts per million (ppm) CO2 has a 5.9–12.7% lower concentration of protein, 3.7–6.5% lower concentration of zinc, and 5.2–7.5% lower concentration of iron. Distributions of pests and diseases will also change, harming agricultural production in many regions. Such impacts will only intensify for as long as we continue to burn fossil fuels12.

How much should you worry about a collapse of the Atlantic conveyor belt?

Posted on 16 December 2024 by Guest Author

This is a re-post from Yale Climate Connections by Bob Henson

In this aerial view, fingers of meltwater flow from the melting Isunnguata Sermia glacier descending from the Greenland Ice Sheet on July 11, 2024, near Kangerlussuaq, Greenland. According to the Programme for Monitoring of the Greenland Ice Sheet (PROMICE), the Greenland Ice Sheet has been losing mass continuously since 1996, with an accumulated loss since 1986 approaching 6,000 metric gigatons, or 6 trillion tons. Meltwater pouring from the Arctic into the far North Atlantic in massive amounts seems to be capable of triggering collapse of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation. (Photo by Sean Gallup/Getty Images)

In this aerial view, fingers of meltwater flow from the melting Isunnguata Sermia glacier descending from the Greenland Ice Sheet on July 11, 2024, near Kangerlussuaq, Greenland. According to the Programme for Monitoring of the Greenland Ice Sheet (PROMICE), the Greenland Ice Sheet has been losing mass continuously since 1996, with an accumulated loss since 1986 approaching 6,000 metric gigatons, or 6 trillion tons. Meltwater pouring from the Arctic into the far North Atlantic in massive amounts seems to be capable of triggering collapse of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation. (Photo by Sean Gallup/Getty Images)

Several high-profile research papers have brought renewed attention to the potential collapse of a crucial system of ocean currents known as the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, or AMOC, as we discussed in part one of this two-part post. Huge uncertainties in both the timing and details of potential impacts of such a collapse remain. Even so, scientists warned in a recent open letter (see below) that “such an ocean circulation change would have devastating and irreversible impacts.”

The AMOC is a vast oceanic loop that carries warm water northward through the uppermost Atlantic toward Iceland and Greenland, where it cools and descends before returning southward. The Gulf Stream, which carries warm water from the tropics toward Europe, is an important section of this loop. Studies of ancient climates reveal that in the distant climate past, AMOC has gone through cycles of collapse that lasted hundreds of years. As we saw in part one, these “off” cycles of the AMOC brought massive environmental changes that would lead to tremendous havoc should they descend on today’s complex, interconnected world.

In part one, we looked at observations from the North Atlantic that suggest a gradual weakening in AMOC strength over the last few decades, but only a marginally significant drop over the past 40 years of AMOC monitoring, including the largest near-surface component, the Gulf Stream.

By no means does this rule out the possibility of a forthcoming AMOC collapse. New research is leading to startlingly specific time frames for when the AMOC might collapse. These studies aren’t without controversy, as we’ll see below. But collectively, they’ve raised the profile of AMOC – and also raised fears that the initial impacts of AMOC collapse could manifest within the lifetimes of many of us.

Stefan Rahmstorf at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research is an eminent researcher who’s studied AMOC and its various modes for more than 30 years. In October 2024, discussing the specter of AMOC collapse, Rahmstorf warned:

Even with a medium likelihood of occurrence, given that the outcome would be catastrophic and impacting the entire world for centuries to come, we believe more needs to be done to minimize this risk.

2024 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming News Roundup #50

Posted on 15 December 2024 by BaerbelW, Doug Bostrom, John Hartz

Listing by Category

Like last week's summary this one contains the list of articles twice: based on categories and based on publication date. Please feel free to let us know in the comments - if you haven't already - which one you prefer. Checking if we assigned the (most) relevant category is also appreciated. Thanks for your help with this!

Climate change impacts

- New York Isn`t Ready to Fight More Wildfires New York could see more frequent and destructive blazes, but the state doesn’t have enough forest rangers and firefighters to respond to the growing threat. by Nathan Porceng, Inside Climate News, Dec 08, 2024

- Climate crisis deepens with 2024 `certain` to be hottest year on record Average global temperature in November was 1.62C above preindustrial levels, bringing average for the year to 1.60C by Damian Carrington, The Guardian, Dec 09, 2024

- This county has an ambitious climate agenda. That`s not easy in Florida. Alachua County is preparing for a more dangerous future, even if the state government won't say "climate." by Sachi Kitajima Mulkey, Grist, Dec 09, 2024

- Autumn 2024 was the warmest in U.S. history, NOAA says "It may also end up being the nation’s warmest year on record.." by Bob Henson, Eye on the Storm, Yale Climate Connections, Dec 9, 2024

- The town that fears losing its high street to climate change - podcast Flooding in Tenbury Wells used to be a once in a generation event, now its happening increasingly frequently. by Presented by Hannah Moore with Jessica Murrayand Helena Horton; produced by Eli Block, Rachel Keenan and Rudi Zygadlo; executive producer Homa Khaleeli, The Guardian, Dec 11, 2024

- Extreme weather disrupts education worldwide Between January 2022 and June 2024, over 400 million students were affected. by YCC Team, Yale Climate Connections, Dec 11, 2024

- November 2024: Earth`s 2nd-warmest November on record The year 2024 is virtually certain to be Earth’s second consecutive warmest year on record. by Jeff Masters, Yale Climate Connections, Dec 12, 2024

- The Night Shift "With extreme heat making it perilous to work during the day, farmers and fisherfolk worldwide are adopting overnight hours. That comes with new dangers." by Ayurella Horn-Muller, Grist, Dec 11, 2024

Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation

- This startup is using AI to ‘supercharge’ crop breeding. It could help protect farmers from the climate crisis by Jack Bantock & Gisella Deputato, Climate, CNN, Dec 2, 2024

- Sabin 33 #6 - Are solar projects harming biodiversity? by Bärbel Winkler, Skeptical Science, Dec 10, 2024

- Scientists advise EU to halt solar geoengineering There’s ‘insufficient scientific evidence’ backing efforts to artificially cool down the planet, according to the European Commission’s scientific advisers. by Justine Calma, The Verge - Science Posts, Dec 09, 2024

Skeptical Science New Research for Week #50 2024

Posted on 12 December 2024 by Doug Bostrom, Marc Kodack

Open access notables:

Climate risk assessments must account for a wide range of possible futures, so scientists often use simulations made by numerous global climate models to explore potential changes in regional climates and their impacts. Some of the latest-generation models have high effective climate sensitivities (EffCS). It has been argued these “hot” models are unrealistic and should therefore be excluded from analyses of climate change impacts. Whether this would improve regional impact assessments, or make them worse, is unclear. Here we show there is no universal relationship between EffCS and projected changes in a number of important climatic drivers of regional impacts. Analyzing heavy rainfall events, meteorological drought, and fire weather in different regions, we find little or no significant correlation with EffCS for most regions and climatic drivers. Even when a correlation is found, internal variability and processes unrelated to EffCS have similar effects on projected changes in the climatic drivers as EffCS. Model selection based solely on EffCS appears to be unjustified and may neglect realistic impacts, leading to an underestimation of climate risks.

Assessing compliance with the human-induced warming goal in the Paris Agreement requires transparent, robust and timely metrics. Linearity between increases in atmospheric CO2 and temperature offers a framework that appears to satisfy these criteria, producing human-induced warming estimates that are at least 30% more certain than alternative methods. Here, for 2023, we estimate humans have caused a global increase of 1.49 ± 0.11 °C relative to a pre-1700 baseline.

Climate change is expected to cause irreversible changes to biodiversity, but predicting those risks remains uncertain. I synthesized 485 studies and more than 5 million projections to produce a quantitative global assessment of climate change extinctions. With increased certainty, this meta-analysis suggests that extinctions will accelerate rapidly if global temperatures exceed 1.5°C. The highest-emission scenario would threaten approximately one-third of species, globally. Amphibians; species from mountain, island, and freshwater ecosystems; and species inhabiting South America, Australia, and New Zealand face the greatest threats. In line with predictions, climate change has contributed to an increasing proportion of observed global extinctions since 1970. Besides limiting greenhouse gases, pinpointing which species to protect first will be critical for preserving biodiversity until anthropogenic climate change is halted and reversed.

A Trojan horse for climate policy: Assessing carbon lock-ins through the Carbon Capture and Storage-Hydrogen-Nexus in Europe, Faber et al., Energy Research & Social Science:

The global energy landscape is entrenched in fossil fuels, shaping modern life profoundly. Germany, a prominent example, grapples with transitioning from its fossil-fuelled infrastructure despite governmental support for decarbonization. Carbon capture and storage (CCS) and hydrogen appear as crucial tools in this transition. A recent partnership between Germany and Norway seeks to leverage Norway's CCS and hydrogen expertise to aid Germany's decarbonization efforts. However, CCS faces criticism for potential mitigation deterrence and carbon lock-ins, perpetuating fossil fuel reliance. This study critically analyses the Norwegian-German CCS-Hydrogen-Nexus, focusing on potential carbon lock-ins. By examining specific projects, institutional frameworks, and industry involvement, we aim to elucidate the partnership's implications for carbon lock-ins. This critical case holds significance for Europe's largest economy and offers insights applicable to CCS technology globally. We find that the current setup perpetuates existing carbon lock-ins both in Germany and Norway. Central problems are the interchangeability of blue and green hydrogen, asset specificity of pipeline and pumping infrastructure and the central role which actors from the fossil fuel industry play in the rollout of the CCS-Hydrogen-Nexus. Our concern is that this approach might entrench the energy system in a socially unjust state. EU policy on blue hydrogen emerged as a factor that helps to avoid carbon lock-ins.

Heat disproportionately kills young people: Evidence from wet-bulb temperature in Mexico, Wilson et al., Science Advances:

Recent studies project that temperature-related mortality will be the largest source of damage from climate change, with particular concern for the elderly whom it is believed bear the largest heat-related mortality risk. We study heat and mortality in Mexico, a country that exhibits a unique combination of universal mortality microdata and among the most extreme levels of humid heat. Combining detailed measurements of wet-bulb temperature with age-specific mortality data, we find that younger people are particularly vulnerable to heat: People under 35 years old account for 75% of recent heat-related deaths and 87% of heat-related lost life years, while those 50 and older account for 96% of cold-related deaths and 80% of cold-related lost life years. We develop high-resolution projections of humid heat and associated mortality and find that under the end-of-century SSP 3–7.0 emissions scenario, temperature-related deaths shift from older to younger people. Deaths among under-35-year-olds increase 32% while decreasing by 33% among other age groups.

Drivers of global tourism carbon emissions, Sun et al., Nature Communications:

Tourism has a critical role to play in global carbon emissions pathway. This study estimates the global tourism carbon footprint and identifies the key drivers using environmentally extended input-output modelling. The results indicate that global tourism emissions grew 3.5% p.a. between 2009-2019, double that of the worldwide economy, reaching 5.2 Gt CO2-e or 8.8% of total global GHG emissions in 2019. The primary drivers of emissions growth are slow technology efficiency gains (0.3% p.a.) combined with sustained high growth in tourism demand (3.8% p.a. in constant 2009 prices). Tourism emissions are associated with alarming distributional inequalities. Under both destination- and resident-based accounting, the twenty highest-emitting countries contribute three-quarters of the global footprint. The disparity in per-capita tourism emissions between high- and low-income nations now exceeds two orders of magnitude. National tourism decarbonisation strategies will require demand volume thresholds to be defined to align global tourism with the Paris Agreement.

From this week's government/NGO section:

How Americans View Climate Change and Policies to Address the Issue, Brian Kennedy and Alec Tyson, Pew Research Center

Americans are split over the economic impact of climate policies. Large businesses and corporations are seen as doing too little on climate change. There is broad support for policies to address climate change. There is widespread frustration with political disagreement over climate change. 64% say climate change currently affects their local community either a great deal or some. Relatively few expect to make major sacrifices in their lifetime due to climate change

Transboundary adaption to climate change: governing flows of water, energy, food and people, Nicholas Simpson and Portia Williams, Overseas Development Institute

Climate change alters transboundary flows that are essential for people and nature, including flows of water, people, energy, and food. Transboundary adaptation can reduce risks by focusing interventions at the origin or source of the climate change impact, along transmission channels, and in the destination country or region. Anticipating, planning for, and managing flows across geographic and sectoral boundaries builds resilience across interconnected systems and populations. Transboundary adaptation is strengthened and more effective when using a nexus approach, which considers how interconnected flows such as hydropower changes affect irrigation and/or energy needs. Greater recognition of governance of transboundary flows within adaptation planning can better identify and manage systemic vulnerabilities that escalate climate change risk. Strengthening governance frameworks to improve cross-border cooperation must be done in conjunction with addressing critical dimensions of vulnerability and promoting the integrated management of shared resources.

148 articles in 52 journals by 811 contributing authors

Physical science of climate change, effects

A pause in the weakening of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation since the early 2010s, Lee et al., Nature Communications Open Access 10.1038/s41467-024-54903-w

Estimated human-induced warming from a linear temperature and atmospheric CO2 relationship, Jarvis & Forster, Nature Geoscience Open Access 10.1038/s41561-024-01580-5

Irreversible changes in the sea surface temperature threshold for tropical convection to CO2 forcing, Park et al., Communications Earth & Environment Open Access 10.1038/s43247-024-01751-7

How unusual is current post-El Niño warmth?

Posted on 11 December 2024 by Zeke Hausfather

This is a re-post from The Climate Brink

As I noted a few months back, despite the end of El Niño conditions in May, global temperatures have remained worryingly elevated. This raises the question of whether this reflects unusual El Niño behavior, or a more persistent change in the underlying climate forcings or feedbacks.

At the time I did a fairly basic analysis comparing the current 2023/2024 El Niño event to the two other recent strong El Niño events – those in 1997/1998 and 2015/2016. However, an “N” of two does not tell us all that much, and the approach was overly simplified in not actually accounting for differing El Niño timing or accurately normalizing for the warming between El Niño events.

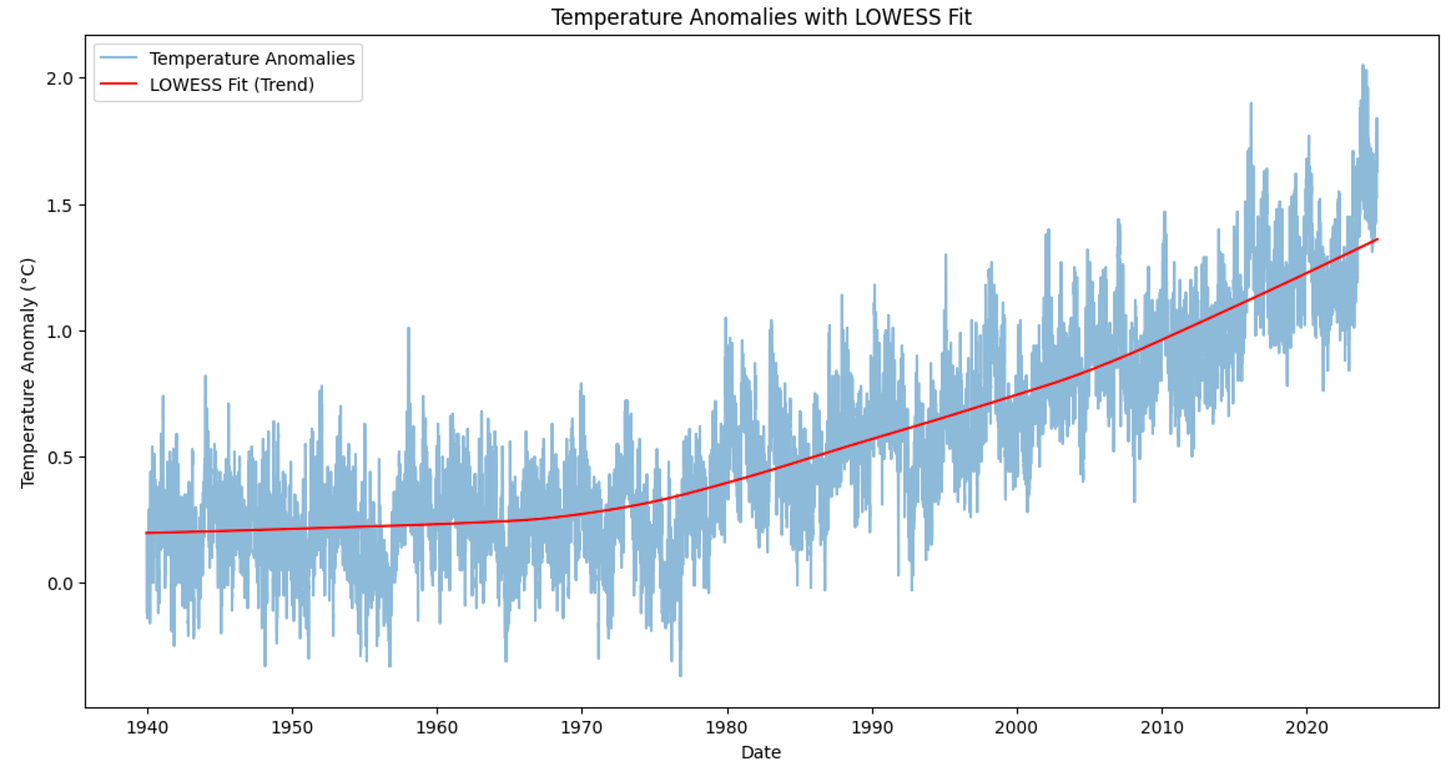

So I decided a more thorough analysis was in order, looking at the evolution of daily temperatures across all El Niño events using the ERA5 reanalysis dataset. Given that this dataset covers the period from 1940 to present, it gives us a six strong El Niño events (Niño 3.4 region > 1.8C) and four more moderate El Niño events (Niño 3.4 region > 1.5C and < 1.8C) to compare with what is happening this year.

It turns out that even looking at the longer record, the evolution of global surface temperatures both before and after the El Niño is unprecedented: temperatures rose earlier than we’ve seen before, and temperatures have remained at elevated levels for a longer period of time.

Isolating El Niño’s effect on warming

To isolate the effect of El Niño events on surface temperatures we first need to remove an important confounding component: the effect of human emissions of CO2 and other greenhouse gases (and aerosols) on global mean surface temperatures.

The figure below shows the approach I used, which involved fitting a locally linear regression (LOWESS) to ERA5 daily temperature anomalies between 1940 and present. This approach is more flexible than a simple linear fit, as it allows for changes in the rate of warming over the course of the record: slow warming pre-1970, faster warming between 1970 and 2005, and a modest acceleration in the rate of warming after 2005.

Sabin 33 #6 - Are solar projects harming biodiversity?

Posted on 10 December 2024 by BaerbelW

On November 1, 2024 we announced the publication of 33 rebuttals based on the report "Rebutting 33 False Claims About Solar, Wind, and Electric Vehicles" written by Matthew Eisenson, Jacob Elkin, Andy Fitch, Matthew Ard, Kaya Sittinger & Samuel Lavine and published by the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia Law School in 2024. Below is the blog post version of rebuttal #6 based on Sabin's report.

The impact of solar development on biodiversity depends on-site specific conditions, such as the local ecosystem, the existing land use, the density of development, and the management practices employed at the site. When applying best practices for project design, including by incorporating pollinator habitat and minimizing soil disturbance, large-scale solar farms on previously developed land, including farmland, can sustain and even increase local biodiversity (Sinha et al. 2018). While developing solar projects on previously undeveloped land may contribute to habitat loss and degradation, as well as negative impacts to local biodiversity, these impacts can be mitigated by avoiding bulldozing and by creating wildlife corridors and habitat patches inside the footprint of the facility where soil and vegetation is not disturbed (Grodsky et al. 2021, Suuronen et al. 2017, Sawyer et al. 2022).

Microclimates within solar farms can enhance botanical diversity, which, in turn can enhance the diversity of the site’s invertebrate and bird populations. In addition, the shade under solar panels can offer critical habitat for a wide range of species, including endangered species1 (also Graham et al. 2021). Shady patches likewise prevent soil moisture loss, boosting plant growth and diversity, particularly in areas impacted by climate extremes (Barron-Gafford et al. 2019).

Proactive measures taken before and after a solar farm’s construction can further enhance biodiversity. Prior to installation, developers can mitigate adverse impacts by examining native species’ feeding, mating and migratory patterns and ensuring that solar projects are not sited in sensitive locations or constructed at sensitive times2. For example, developers can schedule construction to coincide with indigenous reptiles’ and amphibians’ hibernation periods, while avoiding breeding periods.

Additionally, developers can invest in habitat restoration once solar projects have been installed, such as by replanting indigenous flowering species that provide nectar to insects, which also benefits mammals and ground nesting birds. A recent study on the impact of newly-established insect habitat on solar farms in agricultural landscapes found increases in floral abundance, flowering plant species richness, insect group diversity, native bee abundance, and total insect abundance (Walston et al. 2023).

Pollinators play a crucial role in U.S. farming, with more than one third of crop production reliant on pollinators3. Bee populations alone contribute an estimated $20 billion annually to U.S. agriculture production and up to $217 billion worldwide. Recognizing these important contributions, the U.S. Department of Energy’s Solar Technologies Office is currently funding or tracking numerous studies that seek to maximize solar farms’ positive impacts on pollinator-friendly plants4.

As renewables rise, the world may be nearing a climate turning point

Posted on 9 December 2024 by dana1981

This is a re-post from Yale Climate Connections

Climate pollution caused by burning fossil fuels hit a record 37.4 billion metric tons in 2024, marking a 0.8% rise from the previous year – and dashing hopes that a peak in global emissions might occur this year.

That’s according to the latest annual Global Carbon Budget, which underscores a deeper challenge: the world’s ongoing reliance on coal, oil, and gas, which continues to drive emissions and disrupt the climate. The report, organized by a global consortium of scientists centered at the University of Exeter, paints a complex picture of global energy trends, with troubling increases in some areas and signs of progress in others.

Emissions from most wealthy countries fell this year, though by relatively small amounts in many cases. Meanwhile, climate pollution from most developing economies rose, driven by economic growth and a rising demand for energy. Global consumption of coal, oil, and gas all increased, though coal and oil saw less than 1% growth.

While global emissions have yet to reach a clear “peak” – the point at which carbon pollution stops rising and eventually shifts to a consistent decline – there are signs that this turning point could be on the horizon. The rapid deployment of clean technologies like solar panels and electric vehicles (EVs) may help accelerate this shift, although much faster progress will be needed to avoid the worst impacts of climate change.

These global trends have urgent implications for our climate, economies, and ecosystems. To understand what’s behind this year’s record highs and what they signal for the future, let’s explore the key factors shaping climate pollution today.

Arguments

Arguments

(Image credits: The White House, Jonathan Cutrer /

(Image credits: The White House, Jonathan Cutrer /