Latest Posts

Archives

|

|

Explaining climate change science & rebutting global warming misinformation

Global warming is real and human-caused. It is leading to large-scale climate change. Under the guise of climate "skepticism", the public is bombarded with misinformation that casts doubt on the reality of human-caused global warming. This website gets skeptical about global warming "skepticism".

Our mission is simple: debunk climate misinformation by presenting peer-reviewed science and explaining the techniques of science denial, discourses of climate delay, and climate solutions denial.

Posted on 28 December 2025 by BaerbelW, Doug Bostrom

A listing of 28 news and opinion articles we found interesting and shared on social media during the past week: Sun, December 21, 2025 thru Sat, December 27, 2025.

Stories we promoted this week, by category:

Climate Policy and Politics (8 articles)

- Lost Science - She Tracked the Health of Fish That Coastal Communities Depend On Ana Vaz monitored crucial fish stocks in the Southeast and the Gulf of Mexico until she lost her job at NOAA. New York Times, Interview by Austyn Gaffney, Dec 18, 2025.

- Save NCAR Field notes from New Orleans, where I and 20,000 colleagues learned that Trump intends to destroy the National Center for Atmospheric Research. Deep Convection, Adam Sobel, Dec 21, 2025.

- “Destroying Knowledge”: Michael Mann on Trump’s Dismantling of Key Climate Center in Colorado Democracy Now, Amy Goodman, Dec 22, 2025.

- Trump`s shuttering of the National Center for Atmospheric Research is Stalinist | Michael Mann and Bob Ward This is the latest in the relentless purge of climate researchers who refuse to be co-opted by the fossil fuel industry The Guardian, Michael Mann and Bob Ward, Dec 22, 2025.

- Looking Back at a Historic Year of Dismantling Climate Policies The Trump administration has aggressively pulled America away from its global role in climate and environmental research, diplomacy, regulation and investment. New York Times, David Gelles, Dec 23, 2025.

- We analyzed 73,000 articles and found the UK media is divorcing 'climate change' from net zero The Conversation, James Painter, Dec 24, 2025.

- Trump`s anti-climate policies are driving up insurance costs for homeowners, say experts Tariffs, extreme weather events and the president’s funding cuts are contributing to increasing rates, sometimes by double digits. Yale Climate Connections, Marcus Baram, Capital & Main, Dec 24, 2025.

- White House pushes to dismantle leading climate and weather research center PBS News Hour, William Brangham, Dec 26, 2025.

Climate Change Impacts (7 articles)

- Arctic Warming Is Turning Alaska’s Rivers Red With Toxic Runoff A yearly checkup on the region documents a warmer, rainier Arctic and 200 Alaskan rivers “rusting” as melting tundra leaches minerals from the soil into waterways. New York Times, Eric Niiler, Dec 16, 2025.

- Washington State Faces Climate Change Reality After Storms Two weeks of “atmospheric river” deluges took a toll on business in Leavenworth, Wash., and beyond, reminding the region that a warming planet has brought new uncertainty. New York Times, Anna Griffin and Amy Graff, Dec 22, 2025.

- Report: Climate is central to truth and reconciliation for the Sámi in Finland As Finland reckons with its historic mistreatment of the Indigenous Sámi people, climate change complicates the path forward. Grist, Rebecca Egan McCarthy, Dec 23, 2025.

- Oceans are supercharging hurricanes past Category 5 Warming oceans are fueling a surge of extreme, off-the-charts storms—so powerful that scientists say it’s time to invent a whole new hurricane category. Science Direct, AGU, Dec 25, 2025.

- The Guardian view on adapting to the climate crisis: it demands political honesty about extreme weather | Editorial Over the holiday period, the Guardian leader column is looking ahead at the themes of 2026. Today we look at how the struggle to adapt to a dangerously warming world has become a test of global justice The Guardian, Editorial, Dec 26, 2025.

- Six photos show how climate change shaped our world in 2025 This year’s most notable wildfires, hurricanes, droughts, heat waves, and heavy rains were made more devastating and deadly by climate change. Yale Climate Connections, Samantha Harrington, Dec 26, 2025.

- Cyclones, floods and wildfires among 2025`s costliest climate-related disasters Christian Aid annual report’s top 10 disasters amounted to more than $120bn in insured losses The Guardian, Fiona Harvey, Dec 27, 2025.

Read more...

0 comments

Posted on 25 December 2025 by Doug Bostrom, Marc Kodack

Open access notables

Satellite altimetry reveals intensifying global river water level variability, Fang et al., Nature Communications

River water levels (RWLs) are fundamental to hydrology, water resource management, and disaster mitigation, yet the majority of the world’s rivers remain ungauged. Here, using 46,993 virtual stations from Sentinel-3A/B altimetry (2016?2024), we present a global assessment of RWL variability. We find a median global fluctuation of 3.76 m, with pronounced spatial patterns: significant RWL declines across Central North/South America and Western Siberia, and increases across Africa, Oceania, Eastern/Southern Asia, and Northwestern/Central Europe. Seasonality is intensifying in 68% of basins, as high RWLs become more temporally concentrated. Maximum RWLs are declining by 0.88 cm/yr, while minimum RWLs are rising by 1.43 cm/yr. This convergence is reducing seasonal amplitude globally, with the most pronounced changes in the Americas and Central Africa. These shifts coincide with a recent surge in extreme RWL events, particularly after 2021, signaling growing hydrological instability amid concurrent droughts and floods. Our findings underscore the urgent need for adaptive water management in response to accelerating climate pressures.

Gazing into the flames: A guide to assessing the impacts of climate change on landscape fire, Clarke et al., Science Advances

Widespread impacts of landscape fire on ecosystems, societies, and the climate system itself have heightened the need to understand the potential future trajectory of fire under continued climate change. However, the complexity of fire makes climate change impact assessment challenging. The climate system influences fire in many ways, including through vegetation, fuel dryness, fire weather, and ignition. Furthermore, fire’s impacts are highly diverse, spanning threats to human and ecological values and beneficial ecosystem and cultural services. Here, we discuss the art and science of projecting climate change impacts on landscape fire. This not only includes how fire, its drivers, and its impacts are modeled, but critically it also includes how projections of the climate system are developed. By raising and discussing these issues, we aim to foster the development of more robust and useful fire projections, help interpret existing assessments, and support society in charting a course toward a sustainable fire future.

Observed positive feedback between surface ablation and crevasse formation drives glacier acceleration and potential surge, Nanni et al., Nature Communications

Sudden glacier acceleration and instability, e.g. surges, strongly influence glacier ice loss. However, lack of in-situ observations of the involved processes hampers our ability to understand, quantify and model such a role. We present an analysis of the initiation of a surge (Kongsvegen glacier, Svalbard), focusing on the interplay between climatic and glacier-specific drivers. We integrate two decades of in-situ observations (GNSS, borehole and surface seismometers) with runoff simulations, and remotely sensed surface-elevation changes. We show that initial glacier thinning led to localized acceleration and crevassing. Then, we show that stronger surface melt enabled meltwater to reach the glacier bed. This input promotes high basal water pressure and glacier sliding, and in turn further surface crevassing. Our observations suggest that this positive feedback leads to the expansion of the initially localized instability. Our findings highlight mechanisms that could trigger glacier instabilities under a warming atmosphere beyond the High Arctic.

Clinging to power: status threat and attitudes toward the renewable energy transition, Finnegan et al., Environmental Politics

Status threat, defined as the perception that one’s group status, influence, and position in the hierarchy are threatened, has been shown to impact public attitudes across a variety of issue areas. However, the role that status threat plays in forming attitudes on the renewable energy transition is unknown. Using an original survey experiment in the United States, we examine how status threat shapes attitudes toward the renewable energy transition. Our results suggest that status threat, particularly economic status threat, decreases support for renewable energy policies. Since attitudes toward the transition from a fossil fuel-based economy to one dominated by renewable energy remain mixed, our findings suggest that status threat may be directly hindering the renewable energy transition, which is central to efforts to combat climate change.

Who do we trust on climate change, and why?, Sheriffdeen et al., Climate and Development

Trust in climate communicators is a critical determinant of whether the public accepts and acts upon climate change information. Yet most research to date has focused on who is trusted, with less attention to why certain messengers are deemed trustworthy. Using survey data from 6479 participants across 13 countries, this study examines (1) which sources of climate information are trusted, (2) what features make a communicator trustworthy, and (3) how these judgments differ between climate change believers and skeptics. Scientists were the most trusted sources among climate believers, but overall, the most trusted sources are informal and identity-based: “friends and family” and “people like me.” Across the sample, trust was predicted not only by demographic variables but also by specific communicator features: most notably clarity, shared values, sincerity, and being respectful of opposing views. Believers and skeptics prioritized different features, underscoring that trust is not a universal response but shaped by ideological identity. These findings reveal the layered and audience-contingent nature of trust in climate communication. By identifying the features that drive trust across different audiences, this study offers practical guidance for communicators interested in tailoring messages and messengers to more effectively engage the public on climate action.

From this week's government/NGO section:

Climate Science and Natural Resource Litigation, Jessica Wentz, Columbia Law School, Sabin Center for Climate Change Law

Climate change has major implications for sustainable use and conservation of natural resources. Many natural systems are already under severe stress and may be unable to sustain historical use patterns; resource management decisions can also exacerbate or mitigate climate change by affecting the balance of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. The author describes the legal and scientific basis for recognizing agencies’ obligations to assess and respond to climate change, drawing insights from a survey of U.S. litigation involving forests, fisheries, rangelands, and freshwater resources. Litigants have been somewhat successful in driving more rigorous assessments of climate change. However, agencies still frequently conclude that climate impacts are too uncertain or insignificant to warrant a response, and courts will generally defer unless the agency has overlooked or arbitrarily dismissed actionable scientific information. This underscores the importance of collaboration among resource managers, legal advocates, and scientists to develop, disseminate, and communicate scientific information that can meaningfully inform these decisions.

Climate Change in the American Mind: Politics & Policy, Fall 2025, Leiserowitz et al., Yale University and George Mason University

With the first primaries in the 2026 midterm elections just around the corner, the authors found that the economy and the cost of living are the top two issues registered voters say will be “very important” when they decide who they will vote for in the 2026 congressional elections (79% and 78%, respectively). In this context, they also found that 65% of registered voters think global warming is affecting the cost of living in the United States. 49% say policies intended to transition away from fossil fuels and toward clean energy will improve economic growth and provide new jobs (versus 27% who think they will reduce economic growth and cost jobs).

105 articles in 49 journals by 551 contributing authors

Physical science of climate change, effects

Are Trends of Gulf Stream Transport Uniform Along the Florida Shelf?, Torres?Córdoba & Valle?Levinson, Geophysical Research Letters Open Access 10.1029/2025gl118418

Drying Tropical America Under Global Warming: Mechanism and Emergent Constraint, He et al., Geophysical Research Letters Open Access 10.1029/2025gl117131

Read more...

0 comments

Posted on 24 December 2025 by Guest Author

This is a re-post from The Climate Brink by Andrew Dessler

Flooding in the Pacific Northwest (PNW) has recently turned deadly serious, as days of intense rain from a powerful atmospheric river have swollen rivers and caused widespread flooding across the PNW.

Here is why:

The first mechanism is the one you hear about most often: basic thermodynamics. The rule of thumb (the Clausius-Clapeyron relation for the science geeks) is that for every degree Celsius the atmosphere warms, it can hold about 7% more water vapor.

If the atmosphere is a sponge, then a warmer atmosphere is a bigger sponge. This allows the atmospheric river that carries water from the Pacific to soak up more moisture from oceans that are also warmer than average. When that “sponge” hits the Cascades or Olympics and gets wrung out, there is simply more water available to fall than there was in the past.

Because of this, the IPCC says: “Human influence has contributed to the intensification of heavy precipitation in three continents where observational data are more abundant (high confidence) (North America, Europe and Asia).” [IPCC AR6 WG1, Section 11.4.4].

This is another critical factor for the PNW. In the cooler 20th-century, much of the precipitation hitting the Cascades or Olympics would fall as snow. Snow is safe. Snow sits there. It accumulates without drama, effectively “banking” water for the spring and summer months when it is needed most.

However, as freezing levels rise due to warming temperatures, precipitation is increasingly falling as rain. Unlike snow, rain does not sit quietly in the mountains and wait for spring. It runs off immediately.

So when a storm dumps 10 inches of precipitation and half of it falls as snow, the rivers only have to handle 5 inches of water immediately. But if all of it falls as rain because it’s 45°F in the mountains, the rivers have to handle the full 10 inches right now. This climate-enhanced runoff can overwhelm the river system, leading to the widespread flooding we see now.

Read more...

1 comments

Posted on 23 December 2025 by Sue Bin Park

Skeptical Science is partnering with Gigafact to produce fact briefs — bite-sized fact checks of trending claims. You can submit claims you think need checking via the tipline. Skeptical Science is partnering with Gigafact to produce fact briefs — bite-sized fact checks of trending claims. You can submit claims you think need checking via the tipline.

Do solar panels generate more waste than fossil fuels?

Waste from discarded solar panels is dwarfed by the waste from coal, oil, and gas. In addition, solar panel recycling capacity continues to expand and improve. Waste from discarded solar panels is dwarfed by the waste from coal, oil, and gas. In addition, solar panel recycling capacity continues to expand and improve.

A 2023 study estimated that from 2016 – 2050, if power systems do not decarbonize, coal ash would be 300 – 800 times heavier than waste from discarded solar panels, and oily sludge from fossil fuels would be 2 – 5 times heavier.

Currently only about 10 – 15% of panels are recycled in the U.S., but governments and companies are funding additional research and new facilities. Existing plants can already recover around 90 – 95% of a panel’s mass, including glass, aluminum, and steel, and up to 95 – 97% of key semiconductor materials such as cadmium and tellurium.

As solar grows, recycling will cut waste and emissions further, while the bigger waste problem comes from not replacing fossil fuels.

Go to full rebuttal on Skeptical Science or to the fact brief on Gigafact

This fact brief is responsive to quotes such as this one.

Sources

U.S. Department of Energy Photovoltaic Toxicity and Waste Concerns Are Overblown, Slowing Decarbonization--NREL Researchers Are Setting the Record Straight

The Washington Post Scientists found a solution to recycle solar panels in your kitchen

Solar Energy Solar photovoltaic recycling strategies

Nature Energy Research and development priorities for silicon photovoltaic module recycling to support a circular economy

Energy Strategy Reviews An overview of solar photovoltaic panels’ end-of-life material recycling

Columbia Law School Sabin Center for Climate Change Law Rebutting 33 False Claims About Solar, Wind, and Electric Vehicles

Please use this form to provide feedback about this fact brief. This will help us to better gauge its impact and usability. Thank you!

Read more...

0 comments

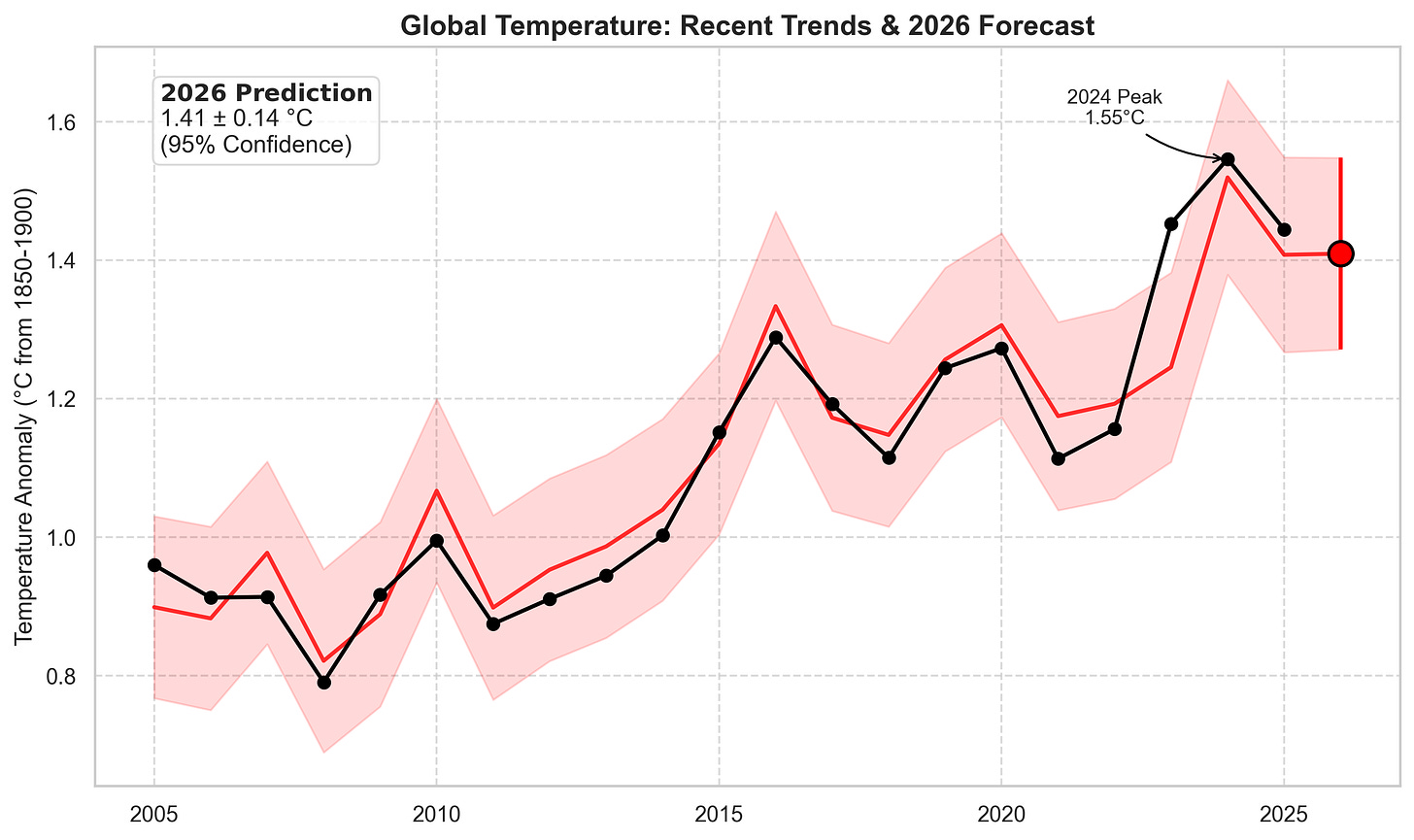

Posted on 22 December 2025 by Zeke Hausfather

This is a re-post from The Climate Brink

Tis the season for global temperature forecasts. The UK Met Office recently released their 2026 prediction, estimating that it is most likely to end up as the second warmest year on record at 1.46C (with a range of 1.34C and 1.58C) relative to the 1850-1900 preindustrial baseline period. This is likely warmer than both 2023 and 2025 and with a small chance of being warmer than 2024.

Not to be outdone, James Hansen released his estimate that 2026 temperatures will also be around 1.47C in the GISTEMP dataset (albeit using a somewhat different 1880-1920 baseline), with the 12 month average dipping down to around 1.4C in the coming months before rising back up by year’s end.

Hansen also adds a prediction for 2027 at 1.7C (1.65C to 1.75C), albeit with the caveat that this refers to the peak 12-month warming during the year rather than the annual average. The prediction is based on an assumed El Nino developing in late 2026 – something that models have suggested is increasingly likely in recent weeks.

I’ve long done year-ahead predictions of global mean surface temperatures (included in the Carbon Brief annual state of the climate report). I base it on a linear regression model that uses a year count, the prior year’s temperature, the latest monthly temperature, and the predicted ENSO (El Nino / La Nina) conditions of the first three months of the coming year, as these factors tend to be the most predictive historically.

The model is fit on historical data since 1970 using the WMO average of six datasets, and I’ve slightly tweaked the model this year to include a squared term for the year count to ensure it is not forced to be too linear (though the effects of this change are minor).

For 2026 I expect global temperatures to be around around 1.41C, with a 95% confidence interval of 1.27C to 1.55C. This means that it is almost certain to be one of the top-4 warmest years, but quite unlikely to exceed 2024’s record. Global temperatures in 2026 will be slightly suppressed by modest La Nina conditions in the tropical Pacific early in the year, while a late-developing El Nino (if it occurs) will primarily affect 2027 temperatures.

Read more...

8 comments

Posted on 21 December 2025 by BaerbelW, Doug Bostrom

A listing of 28 news and opinion articles we found interesting and shared on social media during the past week: Sun, December 14, 2025 thru Sat, December 20, 2025.

Story of the week

As you can see below, five of the six articles in the Climate Policy and Politics category are about the plans to dismantle the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) in Boulder, Colorado. If you live in the US and would like to speak out against this ill-advised plan, you can do so via the action page provided by AGU, the American Geophysical Union: Speak Out to Save NCAR today!

Stories we promoted this week, by category:

Climate Policy and Politics (6 articles)

- Oil executives once booed Canada`s prime minister. Now they cheer him. Mark Carney, once a U.N. special envoy on climate action and finance, is now winning praise from industry but alienating former environmental allies. World, Amanda Coletta, Dec 13, 2025.

- National Center for Atmospheric Research to Be Dismantled, Trump Administration Says Russell Vought, the White House budget director, called the laboratory a source of “climate alarmism.” NYT > Science, Lisa Friedman, Brad Plumer and Jack Healy, Dec 17, 2025.

- Trump administration announces plans to `break up` the National Center for Atmospheric Research The center is one of the world’s premier institutions for studying the atmosphere. Its work has saved countless lives. Yale Climate Connections, Bob Henson and Jeff Masters, Dec 17, 2025.

- We`re all at risk if Trump dismantles this legendary lab Breaking up the National Center for Atmospheric Research would be a "genuinely shocking self-inflicted wound." Grist, Matt Simon, Dec 18, 2025.

- The U.S. Is on the Verge of Meteorological Malpractice The Trump administration says it will dismantle a premier climate center, while somehow keeping weather forecasting intact. The Atlantic, Michelle Nijhuis, Dec 18, 2025.

- Threatening NCAR, Trump administration seeks to extinguish a beacon of climate science The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Benjamin Santer, Dec 19, 2025.

Climate Change Impacts (5 articles)

- Guest post: How the Greenland ice sheet fared in 2025 Greenland is closing in on three decades of continuous annual ice loss, with 1995-96 being the last year in which the giant ice sheet grew in size. Carbon Brief, Dr Martin Stendel and Prof Ruth Mottram, Dec 15, 2025.

- TCB quick hit: How climate change broke the Pacific Northwest`s plumbing It’s not just wetter storms—it’s also the important shift from snow to rain The Climate Brink, Andrew Dessler, Dec 15, 2025.

- Record-breaking climate change: 2025 edition Dr Gilbz on Youtube, Ella Gilbert, Dec 15, 2025.

- Arctic endured year of record heat as climate scientists warn of `winter being redefined` Region known as ‘world’s refrigerator’ is heating up as much as four times as quickly as global average, Noaa experts say The Guardian, Oliver Milman, Dec 16, 2025.

- Canada's North is warming from the ground up, and our infrastructure isn't ready The Conversation, Mohammadamin Ahmadfard, Ibrahim Ghalayini, Seth Dworkin, Dec 17, 2025.

Read more...

0 comments

Posted on 18 December 2025 by Doug Bostrom, Marc Kodack

Open access notables

Widespread Increase in Atmospheric River Frequency and Impacts Over the 20th Century, Scholz & Lora, AGU Advances

Atmospheric rivers (ARs) play a dominant role in water resource availability in many regions, and can cause substantial hazards, including extreme precipitation, flooding, and moist heatwaves. Despite this, there is substantial uncertainty about recent and ongoing changes in AR frequency and impacts. Here, we place recent observed trends in their longer-term context using AR records extending back to 1940. Our results show that AR frequency has increased broadly across the midlatitudes, bridging the apparent discrepancy between the observed satellite-era poleward shift and the general increase simulated in climate change projections. This increase in AR frequency enhances AR-associated precipitation and snowfall across their region of influence in the mid- and high-latitudes. We also find that, despite warmer surface temperatures associated with ARs, there is a decrease in the magnitude of AR-associated temperature anomalies in high-latitude regions due to Arctic amplification. An increase in AR-associated humid heatwaves underscores the societal importance of changing AR activity.

Reduction of Residence Time of Air in the Arctic Since the 1980s, Plach et al., Geophysical Research Letters

The Arctic has seen dramatic changes in recent decades. Here we use a simple metric, the Arctic residence time of air, that is, the time air spends uninterruptedly north of 70N, to evaluate how these changes have affected the high-latitude atmospheric circulation in the last 40 years. We find that, on average, near-surface air resides between 7 (winter) and 12 (summer) days in the Arctic. This residence time has decreased almost year-round since the 1980s, especially pronounced in the seasonal transition periods (fall: 0.9 days; spring: 1.4 days). The more pronounced reduction in spring also affects higher atmospheric layers. Our analysis indicates that this reduction is likely linked to the observed sea ice loss, decrease in snow cover, and increase in temperature. Furthermore, it indicates a speed-up of the circulation, effectively making the Arctic less isolated and more prone to influences from mid-latitudes.

Peak glacier extinction in the mid-twenty-first century, Van Tricht et al., Nature Climate Change

Projections of glacier change typically focus on mass and area loss, yet the disappearance of individual glaciers directly threatens culturally, spiritually and touristically significant landscapes. Here, using three global glacier models, we project a sharp rise in the number of glaciers disappearing worldwide, peaking between 2041 and 2055 with up to ~4,000 glaciers vanishing annually. Regional variability reflects differences in average glacier size, local climate, the magnitude of warming and inventory completeness.

Countering the Climate Change Counter Movement: Six lessons from Canada's climate delays, Lloyd & Rhodes, Energy Research & Social Science

The global transition away from fossil fuels is dangerously delayed. While climate delays are a complex issue, the fossil-fuel funded Climate Change Counter Movement represents a key culprit that is worthy of greater attention than it receives. As such, this article uses Canada as a case study to highlight the Movement's role in delaying climate action in the West, and to suggest six strategies to counteract their influence. We collate evidence demonstrating the Climate Change Counter Movement's influence over the Canadian state, its economy and its people, and directly linking elite members of the Movement to post-truth narratives that deny the reality of climate change, and delay climate policy. Concerningly, we also find evidence that these “climate delay discourses” can rapidly evolve to exploit new contexts and cultures, and are already being repeated by unassociated members of the general public. In order to spur action against the Climate Change Counter Movement, we combine insights from our case study with a narrative review of international research to suggest six strategies to counteract their influence, alongside associated directions for future research. These strategies would see climate policy advocates: reflect upon their own position; develop knowledge of the Climate Change Counter Movement's actions; use that knowledge to hold them legally accountable for those actions; reverse the effects they have already had on the general population; push “passively supported” policies to advance climate action even when public appetites are low; and challenge the economic and cultural roots of the Climate Change Counter Movement's power.

From this week's government/NGO section:

Arctic Report Card 2025, Druckenmiller et al., National Oceanic and Atmospheric Organization

Now in its 20th year, the Arctic Report Card (ARC) 2025 provides a clear view of a region warming far faster than the rest of the planet. Along with reports on the state of the Arctic’s atmosphere, oceans, cryosphere, and tundra, this year’s report highlights major transformations underway—atlantification bringing warmer, saltier waters northward, boreal species expanding northward into Arctic ecosystems, and “rivers rusting” as thawing permafrost mobilizes iron and other metals. Across these changing landscapes, sustained observations and strong research partnerships, including those led by communities and Indigenous organizations, remain essential for understanding and adaptation.

Big Oil’s Deceptive Climate Ads. How Four Oil Majors Sold False Promises from 2000-2025, Charlotte Marcil, Center for Climate Integrity

While knowingly fueling the climate crisis, four oil majors — BP, Chevron, ExxonMobil, and Shell — spent 25 years running deceptive advertising campaigns to falsely reposition themselves as partners in the fight against climate change. The author examines more than 300 unique climate-related advertisements across seven categories of deception, highlighting Big Oil’s modern campaign of lies.

125 articles in 52 journals by 826 contributing authors

Physical science of climate change, effects

Contributions of Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation, Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation, and global oceanic warming to the secular change in United States tornado occurrence, Zhao et al., Atmospheric Research 10.1016/j.atmosres.2025.108689

Large Uncertainty in Arctic Warming Driven by the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, Hahn et al., Geophysical Research Letters Open Access 10.1029/2025gl119720

Read more...

0 comments

Posted on 17 December 2025 by Zeke Hausfather

This is a re-post from Carbon Brief

The past three years have been exceptionally warm globally.

In 2023, global temperatures reached a new high, after they significantly exceeded expectations.

This record was surpassed in 2024 – the first year where average global temperatures were 1.5C above pre-industrial levels.

Now, 2025 is on track to be the second- or third-warmest year on record.

What has caused this apparent acceleration in warming has been subject to a lot of attention in both the media and the scientific community.

Dozens of papers have been published investigating the different factors that could have contributed to these record temperatures.

In 2024, the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) discussed potential drivers for the warmth in a special section of its “state of the global climate” report, while the American Geophysical Union ran a session on the topic at its annual meeting.

In this article, Carbon Brief explores four different factors that have been proposed for the exceptional warmth seen in recent years. These are:

Carbon Brief’s analysis finds that a combination of these factors explains most of the unusual warmth observed in 2024 and half of the difference between observed and expected warming in 2023.

However, natural fluctuations in the Earth’s climate may have also played a role in the exceptional temperatures, alongside signs of declining cloud cover that may have implications for the sensitivity of the climate to human-caused emissions.

Read more...

0 comments

Posted on 16 December 2025 by Sue Bin Park

Skeptical Science is partnering with Gigafact to produce fact briefs — bite-sized fact checks of trending claims. You can submit claims you think need checking via the tipline. Skeptical Science is partnering with Gigafact to produce fact briefs — bite-sized fact checks of trending claims. You can submit claims you think need checking via the tipline.

Are toxic heavy metals from solar panels posing a threat to human health?

Toxic heavy metals in solar panels are locked in stable compounds and sealed behind tough glass, preventing escape into air, water, or soil at harmful levels. Toxic heavy metals in solar panels are locked in stable compounds and sealed behind tough glass, preventing escape into air, water, or soil at harmful levels.

Most concern focuses on cadmium and lead. 40% of new U.S. panels use cadmium telluride, which does not dissolve in water, easily turn to gas, or approach the toxicity of pure cadmium.

During manufacturing and disposal, heavy metals are handled under safety and waste rules. Per unit of electricity, solar releases far less heavy metals than fossil fuels.

Studies and safety reviews find that heavy metals pose no qualifiable danger to health during the regular manufacture, use, or regulated disposal of solar panels.

Go to full rebuttal on Skeptical Science or to the fact brief on Gigafact

This fact brief is responsive to quotes such as this one.

Sources

NREL Polycrystalline Thin-Film Research: Cadmium Telluride

NC Clean Energy Technology Center Health and Safety Impacts of Solar Photovoltaics

American Chemical Society Emissions from Photovoltaic Life Cycles

EPA Solar Panel Frequent Questions

Massachusetts Department of Energy Resources Questions & Answers: Ground-Mounted Solar Photovoltaic Systems

EPA Ecological Soil Screening Level

Columbia Law School Sabin Center for Climate Change Law Rebutting 33 False Claims About Solar, Wind, and Electric Vehicles

Please use this form to provide feedback about this fact brief. This will help us to better gauge its impact and usability. Thank you!

Read more...

0 comments

Posted on 15 December 2025 by Ken Rice

This is a re-post from And Then There's Physics

Since effective communication often involves repeating things, I thought I would repeat what others have pointed out already. The underlying issue is that there is a narrative in the climate skeptosphere suggesting that extreme weather events are not becoming more common, or that we can’t yet attribute changes in most extreme weather types to human influences (as suggested in the recent DoE climate report).

Table 12.12 from the IPCC AR6 WGI report. Table 12.12 from the IPCC AR6 WGI report.This is often based on the Table shown on the right, taken from Chapter 12 of the IPCC AR6 WGI report. As, I think, originally pointed out by Tim Osborn, this table is not suggesting that we haven’t yet detected changes in most extreme weather events, or haven’t managed to attribute a human influence. It’s essentially considering if, or when, a signal has/will have emerged from the noise. Formally, emergence is defined as the magnitude of a particular event increasing by more than 1 standard deviation of the normal variability.

Read more...

13 comments

Posted on 14 December 2025 by BaerbelW, Doug Bostrom

A listing of 28 news and opinion articles we found interesting and shared on social media during the past week: Sun, December 7, 2025 thru Sat, December 13, 2025.

Stories we promoted this week, by category:

Climate Change Impacts (8 articles)

- When climate risk hits home, people listen: Local details can enhance disaster preparedness messaging Phys.org, Stockholm School of Economics, Dec 08, 2025.

- A 30-year-old sea level rise projection has basically come true Even without today’s advanced modeling tools, scientists made a ‘remarkably’ accurate estimate. Yale Climate Connections, YCC Team, Dec 08, 2025.

- Nearly 8,000 animal species are at risk as extreme heat and land-use change collide Phys.org, University of Oxford, Dec 09, 2025.

- 2025 `virtually certain` to be second- or third-hottest year on record, EU data shows Copernicus deputy director says three-year average for 2023 to 2025 on track to exceed 1.5C of heating for first time The Guardian, Ajit Niranjan, Dec 09, 2025.

- Global warming amplifies extreme day-to-day temperature swings, study shows Phys.org, Li Yali, Dec 10, 2025.

- 3rd warmest on record (again): November 2025 keeps a hot global streak going This year is likely to end up as the 2nd- or 3rd-warmest year on record, despite the lack of a planet-warming El Niño event. Yale Climate Connections, Jeff Masters and Bob Henson, Dec 11, 2025.

- Climate change is stealing rain and snow from the Colorado River, new report says Global weirding all across the board; while the US PNW reels under juiced-up atmospheric rivers, the SW US is dessicating as predicted by climate models. The Colorado Sun, Katie Hawkinson , Dec 12, 2025.

- In Alaska`s warming Arctic, photos show an Indigenous elder passing down hunting traditions An Inupiaq elder teaches his great-grandson to hunt in rapidly warming Northwest Alaska where thinning ice, shifting caribou migrations and severe storms are reshaping life The Independent News, Annika Hammerschlag, Dec 13, 2025.

Climate Policy and Politics (5 articles)

- As natural disasters tear through Asia, politicians ignore climate at their own peril ABC News, Karishma Vyas, Dec 06, 2025.

- The EPA is wiping mention of human-caused climate change from its website Some pages have been tweaked to emphasize ‘natural forces’; others have been deleted entirely. Washington Post, Shannon Osaka, Dec 9, 2025.

- EPA eliminates mention of fossil fuels in website on warming's causes. Scientists call it misleading Phys.org, Seth Borenstein, Dec 10, 2025.

- The EPA website got the basics of climate science right. Until last week. The Trump administration purged 80 pages of facts about climate change — including that it's caused by humans Grist, Kate Yoder, Dec 11, 2025.

- Climate change is straining Alaska's Arctic. A new mining road may push the region past the brink In Northwest Alaska, a proposed 211-mile mining road has divided an Inupiaq community already devastated by climate change The Independent News, Annika Hammerschlag, Dec 11, 2025.

Read more...

0 comments

Posted on 11 December 2025 by Doug Bostrom, Marc Kodack

Open access notables

Detectability of Post-Net Zero Climate Changes and the Effects of Delay in Emissions Cessation, King et al., Earth's Future

There is growing interest in how the climate would change under net zero carbon dioxide emissions pathways as many nations aim to reach net zero in coming decades. In today's rapidly warming world, many changes in the climate are detectable, even in the presence of internal variability, but whether climate changes under net zero are expected to be detectable is less well understood. Here, we use a set of 1000-year-long net zero carbon dioxide emissions simulations branching from different points in the 21st century to examine detectability of large-scale, regional and local climate changes as time passes under net zero emissions. We find that even after net zero, there are continued detectable changes to climate for centuries. While local changes and changes in extremes are more challenging to detect, Southern Hemisphere warming and Northern Hemisphere cooling become detectable at many locations within a few centuries under net zero emissions. We also study how detectable delays in achieving emissions cessation are across climate indices. We find that for global mean surface temperature and other large-scale indices, such as Antarctic and Arctic sea ice extent, the effects of an additional 5 years of high greenhouse gas emissions are detectable. Such delays in emissions cessation result in significantly different local temperatures for most of the planet, and most of the global population. The long simulations used here help with identifying local climate change signals. Multi-model frameworks will be useful to examine confidence in these changes and improve understanding of post-net zero climate changes.

From short-term uncertainties to long-term certainties in the future evolution of the Antarctic Ice Sheet, Coulon et al., Nature Communications

Robust projections of future sea-level rise are essential for coastal adaptation, yet they remain hampered by uncertainties in Antarctic ice-sheet projections–the largest potential contributor to sea-level change under global warming. Here, we combine two ice-sheet models, systematically sample parametric and climate uncertainties, and calibrate against historical observations to quantify Antarctic ice-sheet changes to 2300 and beyond. By 2300, the projected Antarctic sea-level contributions range from -0.09 m to +1.74 m under low emissions (SSP1-2.6, outer limits of 5-95% probability intervals), and from +0.73 m to +5.95 m under very high emissions (SSP5-8.5). Irrespective of the wide range of uncertainties explored, large-scale Antarctic ice-sheet retreat is triggered under SSP5-8.5, while reaching net-zero emissions well before 2100 strongly reduces multi-centennial ice loss. Yet, even under such strong mitigation, a significant sea-level contribution could still result from West Antarctica. Our results suggest that current mitigation efforts may not be sufficient to avoid self-sustained Antarctic ice loss, making emission decisions taken in the coming years decisive for future sea-level rise.

Declining number of northern hemisphere land-surface frozen days under global warming and thinner snowpacks, Hatami et al., Communications Earth & Environment

Freeze–thaw processes shape ecosystems, hydrology, and infrastructure across northern high latitudes. Here we use satellite-based observations from 1979–2021 across 47 northern hemisphere ecoregions to examine changes in the number of frozen land-surface days per year. We find widespread declines, with 70% of ecoregions showing significant reductions, primarily linked to rising air temperatures and thinning snowpacks. Causal analysis demonstrates that air temperature and snow depth exert consistent controls on the number of frozen days. A trend-informed assessment based on historical observations suggests a potential average loss of more than 30 frozen days per year by the end of the century, with the steepest decreases in Alaska, northern Canada, northern Europe, and eastern Russia. Scenario-based analysis indicates that each 1 °C increase in air temperature reduces frozen days by ~6-days, while each 1 cm decrease in snow depth leads to a ~ 3-day reduction. These shifts carry major ecological and socio-economic implications.

Timing of a future glaciation in view of anthropogenic climate change, Kaufhold et al., Communications Earth & Environment

Human activities are expected to delay the next glacial inception because of the long atmospheric lifetime of anthropogenic CO2. Here we present Earth system model simulations for the next 200,000 years with dynamic ice sheets and interactive atmospheric CO2, exploring how emissions will impact a future glacial inception. Historical emissions (500 PgC) are unlikely to delay inception, expected to occur under natural conditions around 50,000 years from now, while a doubling of current emissions (1000 PgC) would delay inception for another 50,000 years. Inception is generally expected within the next 200,000 years for emissions up to 5000 PgC. Our model results show that assumptions about the long-term balance of geological carbon sources and sinks has a strong impact on the timing of the next glacial inception, while millennial-scale variability in the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation influences the exact timing. This work highlights the long-term impact of anthropogenic CO2 on climate.

From this week's government/NGO section:

Extreme Heat and the Shrinking Diurnal Range. A Global Evaluation of Oppressive Air Mass Character and Frequency, Kalkstein et al., Climate Resilience for All

As country leaders focus on avoiding breaching the +1.5°C threshold of the Paris Agreement, nighttime temperatures in cities are soaring at a rate of as much as 10 times higher than daytime temperatures. The authors examine how nighttime temperatures are rising at alarming rates in cities across the globe. The authors found that cities are not only experiencing on average an extra day of extreme heat every six years, but also—even more alarmingly—nighttime temperatures are rising much more rapidly than daytime highs in a majority of the cities worldwide. Women are particularly vulnerable to nighttime heat. Physiological factors make them more sensitive to higher temperatures, and societal norms and inequalities amplify their risk. Often shouldering a greater burden of care for older relatives and the sick, it is usually a woman who stays awake when their family member cannot sleep, sacrificing her own rest and recovery, to care for them. And gender norms, or the threat of violence can keep women from sleeping outside or with windows open, making thermal relief even harder to find.

Extreme Heat, Gender and Health - A dialogue towards climate resilient adaptation, Kumar et al., Multiple

India's rapidly growing cities are becoming dangerous for pregnant women as extreme heat combines with inadequate housing and fragmented health systems to create life-threatening conditions. The Heat in Pregnancy – India (HiP-I) project brought together leading experts to examine this escalating crisis and identify urgent solutions. Policies must be tailored to local realities. India-specific research is necessary to understand the impact of heat on pregnancy, and early warning systems should incorporate humidity and nighttime temperatures, rather than focusing solely on peak daytime heat. Coordination across sectors is essential. Governance fragmentation leaves pregnant women in informal settlements without protection, while urban planning, health systems, water management, and housing policy continue to operate in silos. Breaking these silos is key to effective adaptation.

Highlights from the extreme heat and agriculture report, Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations and the World Meteorological Organization

The authors explore the impact of extreme heat on agricultural producers and on crops, livestock, fisheries and aquaculture, and forests worldwide. Drawing on recent scientific evidence and country case studies, they highlight the independent and compound risks posed by extreme heat, underscores the urgency of mitigation, and presents pathways to strengthen resilience and sustainability across agricultural sectors.

135 articles in 58 journals by 831 contributing authors

Physical science of climate change, effects

Antarctic Bottom Water in a changing climate, Jacobs, Nature Reviewss Earth & Environment, 10.1038/s43017-025-00750-2

Hot droughts in the Amazon provide a window to a future hypertropical climate, Chambers et al., Nature 10.1038/s41586-025-09728-y

Read more...

0 comments

Posted on 10 December 2025 by dana1981

This is a re-post from Yale Climate Connections

The electric car market is booming – just not in the United States.

One-quarter of new cars sold around the world so far in 2025 have been electric. That share is forecast to continue rising rapidly in coming years, reaching one-half in the early 2030s.

But the electric share of new car sales in the U.S. has plateaued at a mere 10% since 2023, and the Trump administration has implemented policies and regulatory changes that have slammed the brakes on a shift to EVs.

As a result, many developing nations in regions like Southeast Asia are passing the U.S. in EV adoption, while China and a number of European countries like Norway (as Will Ferrell comedically informed us in a GM advertisement) are leaving the rest of the world in their dust. On the sales side, China’s advanced EV manufacturing has allowed the country to take the lead in global auto exports.

Road transportation accounts for about 12% of global climate emissions. So electric vehicles are a key climate solution, “highly recommended” by the experts at Project Drawdown, a nonprofit organization that researches the most effective climate solutions. They estimate that widespread EV adoption could reduce climate pollution worldwide by over 2 billion tons of carbon dioxide per year.

Although alternative transportation methods like walking, biking, and public transport are the lowest-emissions options, replacing fossil-fueled cars with EVs also cuts pollution. The International Energy Agency estimates that EV deployment will account for about 10% of the total emissions prevented by climate policies around the world in 2030.

But the global and American trajectories in this key clean energy technology are turning in different directions. And with most other countries racing to adopt EVs as a more efficient, cost-effective, and cleaner mode of transportation, China’s growing dominance of this technology may help that country become the next global economic superpower.

Read more...

0 comments

Posted on 9 December 2025 by Sue Bin Park

Skeptical Science is partnering with Gigafact to produce fact briefs — bite-sized fact checks of trending claims. You can submit claims you think need checking via the tipline. Skeptical Science is partnering with Gigafact to produce fact briefs — bite-sized fact checks of trending claims. You can submit claims you think need checking via the tipline.

Are electromagnetic fields from solar farms harmful to human health?

Electromagnetic fields from solar farms are far too weak to harm human health and fall well within accepted safety limits for exposure. Electromagnetic fields from solar farms are far too weak to harm human health and fall well within accepted safety limits for exposure.

Solar equipment emits non-ionizing radiation, meaning it has enough energy to move atoms in a molecule but not enough to remove electrons or damage DNA. Solar farm EMFs are even less energetic than other forms of common non-ionizing radiation such as radio waves, infrared, or visible light.

Even when standing directly beside the largest-scale equipment, EMF levels measure around 1,050 milligauss (mG), lower than exposure from using an electric can opener (up to 1,500 mG) and well below exposure limits (around 2,000 mG). At distances typical of real-world exposure – 9 feet from a residential inverter or 150 feet from a utility-scale inverter – field strength falls to 0.5 mG or less.

Scientific reviews find no consistent evidence of negative health impacts from EMFs produced by solar farms.

Go to full rebuttal on Skeptical Science or to the fact brief on Gigafact

This fact brief is responsive to quotes such as this one.

Sources

NC State University Health and Safety Impacts of Solar Photovoltaics

Massachusetts Department of Energy Resources Ground-Mounted Solar Photovoltaic Systems

Massachusetts Clean Energy Center STUDY OF ACOUSTIC AND EMF LEVELS FROM SOLAR PHOTOVOLTAIC PROJECTS

Columbia Law School Sabin Center for Climate Change Law Rebutting 33 False Claims About Solar, Wind, and Electric Vehicles

Please use this form to provide feedback about this fact brief. This will help us to better gauge its impact and usability. Thank you!

Read more...

0 comments

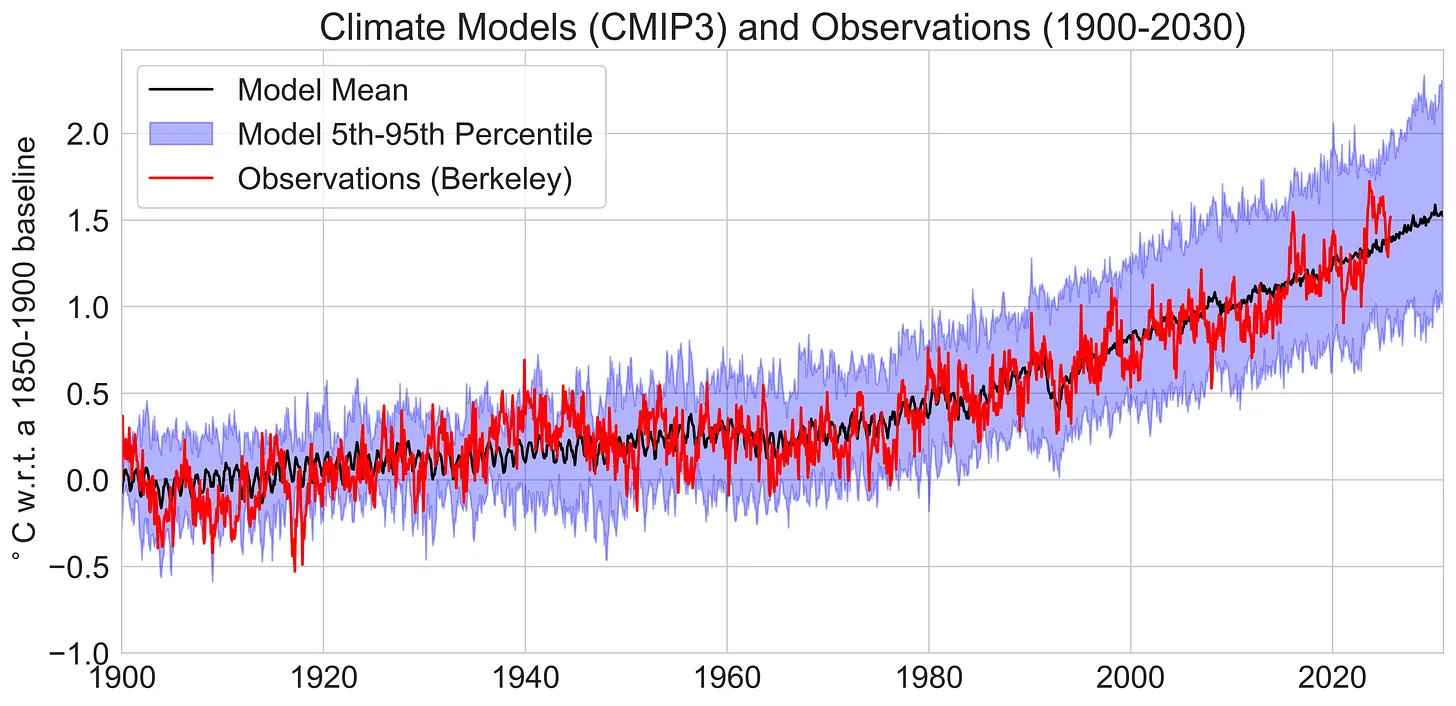

Posted on 8 December 2025 by Zeke Hausfather

This is a re-post from The Climate Brink

The extreme global temperatures of the past few years have led a lot of people to ask me if the world is warming faster than expected.

To answer that, we need to look at how well climate models reproduce observed global mean surface temperatures. Here I will look at the last three generations of climate models (CMIP3, CMIP5, and CMIP6) as well as a version of the latest generation of models (CMIP6) that excludes the so-called “hot models” whose climate sensitivity is higher than the range deemed likely in the most recent IPCC report.

It turns out that that the resulting picture is complex. Earlier generations of models better reproduce the rate of warming observed since 1970, while the latest generation better captures the rate of warming in the last two decades. Whether this is evidence that warming is occurring faster than earlier generations of climate models expected will depend on how much of the recent warming acceleration is here to stay, and how much is being driven by short-term climate variability. While a bit unsatisfying as an answer, it probably remains too early to tell.

This post represents an update of my 2023 TCB post on model-observation comparisons, albeit with a fair bit of new analysis included (and two more years of observations!).

One classic way to compare models and observations is to look at how temperatures have changed over time, compared to the multi-model mean and 5th to 95th percentile range across individual climate model runs. This is generally done using a single run for each unique climate model (in cases where modeling groups submit more than one modeling run) in order to ensure that each gets equal weight in the analysis.

For example, here are the 23 unique CMIP3 climate models that accompanies the IPCC 4th Assessment Report published in 2007. These models were run around 2004, and use historical data on CO2 concentrations, volcanoes, and other climate forcings through the year 2000 (and the SRES scenarios thereafter, with the middle-of-the-road A1B scenario shown here).

Read more...

0 comments

Posted on 7 December 2025 by BaerbelW, Doug Bostrom

A listing of 28 news and opinion articles we found interesting and shared on social media during the past week: Sun, November 30, 2025 thru Sat, December 6, 2025.

Stories we promoted this week, by category:

Climate Change Impacts (8 articles)

- Where no one really dies One of the most wonderful people I've met as a climate journalist died this year. But Shelton Kokeok, like everyone in Shishmaref, lives on through his name. Basline on Substack, John D. Sutter, Nov 30, 2025.

- Will Glacier Melt Lead to Increased Seismic Activity in Mountain Regions? State of the Planet, Emily Cohen, Dec 01, 2025.

- In Burned Forests, the West`s Snowpack Is Melting Earlier As blazes expand to higher elevations, the impacts cascade downstream. Inside Climate News, Mitch Tobin, Dec 02, 2025.

- Global heating and other human activity are making Asia`s floods more lethal Much improved response systems are struggling to cope with ever more powerful and destructive storms The Guardian, Ajit Niranjan, Dec 02, 2025.

- COP30 Is Over. But for the World`s Most Vulnerable, the Crisis Is Ongoing. State of the Planet, Anyieth Philip Ayuen, Dec 04, 2025.

- An Alaskan Village Confronts Its Changing Climate: Rebuild or Relocate? After a devastating storm, the people who fled a remote coastal village face an existential question. New York Times, Scott Dance and Katie Basile, Dec 05, 2025.

- Climate change is boosting health care costs An online tool helps businesses figure out how much climate change could increase what they pay for their employees’ health care Yale Climate Connections, YCC Team, Dec 05, 2025.

- Climate change threatens Europe's remaining peatlands, study shows Phys.org, ERINN Innovation, Dec 06, 2025.

International Climate Conferences and Agreements (6 articles)

- Many Fighting Climate Change Worry They Are Losing the Information War Shifting politics, intensive lobbying and surging disinformation online have undermined international efforts to respond to the threat. New York Times, Lisa Friedman and Steven Lee Myers, Nov 30, 2025.

- Paris Climate Agreement At 10: Did It Do Anything? ClimateAdam & Dr Gilbz on Youtube, Adam Levy and Ella Gilbert, Nov 30, 2025.

- Are UN climate summits a waste of time? No, but they are in dire need of reform The Conversation, Arthur Wyns, Dec 01, 2025.

- `The dinosaurs didn`t know what was coming, but we do`: Marina Silva on what needs to follow Cop30 Exclusive: Brazil’s environment minister talks about climate inaction and the course we have to plot to save ourselves and the planet. The Guardian, Jonathan Watts, Dec 03, 2025.

- News roundup: COP30 wasn`t a complete failure Nuanced readings dig into what comes next for international climate politics and the people-powered movements pushing for meaningful solutions. Yale Climate Connections, SueEllen Campbell, Dec 03, 2025.

- Al Gore's case for optimism Gore talks to HEATED about COP30, the Gates memo, and why he thinks billionaires should face far more scrutiny in the climate fight. HEATED, Emily Atkin, Dec 04, 2025.

Read more...

0 comments

Posted on 4 December 2025 by Doug Bostrom, Marc Kodack

Open access notables

Bedrock uplift reduces Antarctic sea-level contribution over next centuries, van Calcar et al., Nature Communications

The contribution of the Antarctic Ice Sheet to barystatic sea-level rise could be as high as eight metres around 2300 but remains deeply uncertain. Ice sheet retreat causes bedrock uplift, which can exert a stabilising effect on the grounding line. Yet, sea-level projections exclude bedrock adjustment, use simplified Earth structures or omit the uncertainty in climate response and Earth structure. We show that the grounding line retreat is delayed by 50 to 130 years and the barystatic sea-level contribution reduced by 9–23% when the heterogeneity of the solid Earth is included in a coupled ice – bedrock model under different emission scenarios till 2500. The effect of the solid Earth feedback in ice sheet projections can be twice as large as the uncertainty due to differences between climate models. We emphasise that realistic Earth structures should be considered when projecting the Antarctic contribution to barystatic sea-level rise on centennial time scales.

Loss of vegetation functions during the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum, Rogger et al., Nature Communications

The Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM) around 56 million years ago was a 5–6°C global warming event that lasted for approximately 200 kyr. A warming-induced loss and a 70–100 kyr lagged recovery of biospheric carbon stocks was suggested to have contributed to the long duration of the climate perturbation. Here, we use a trait-based, eco-evolutionary vegetation model to test whether the PETM warming exceeded the adaptation capacity of vegetation systems, impacting the efficiency of terrestrial organic carbon sequestration and silicate weathering. Combined model simulations and vegetation reconstructions using PETM palynofloras suggest that warming-induced migration and evolutionary adaptation of vegetation were insufficient to prevent a widespread loss of productivity. We conclude that global warming of the magnitude as during the PETM could exceed the response capacity of vegetation systems and cause a long-lasting decline in the efficiency of vegetation-mediated climate regulation mechanisms.

Marine heatwave decimates fire coral populations in the Caribbean, Dell’Antonio et al., Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

Marine heatwaves (MHW) are common destructive events affecting coral reefs. After decades of degradation, the shallow reefs of the United States Virgin Islands have been depleted of scleractinian corals, leaving abundant colonies of the hydrozoan fire coral Millepora dominating the coral community. This dominance ended in 2024 after 84% of Millepora colonies over 43 km of shore were killed by a MHW that brought the hottest October in the 36 y since monitoring began. In August 2024, dead Millepora were rare on these reefs, but by March 2025, severe bleaching created a fire coral graveyard. Decimation of the fire coral biotope shows that these short-term coral winners are unlikely to be future reef builders.

Climate Change Favors African Malaria Vector Mosquitoes, van der Deure et al., Global Change Biology

Here, we for the first time estimate the future human exposure to each of six dominant African malaria vector species. Using an extensive mosquito observation dataset, robust species distribution modeling, and climate and land-use data, we investigate the climatic niches of six dominant African malaria vector species and map out their differing responses to climate and land use change across sub-Saharan Africa. Projections of future vector suitability identify three species that are likely to experience a substantial expansion of suitable habitat: Anopheles gambiae, Anopheles coluzzii, and Anopheles nili s.l. By combining these projections with human population density data, we conservatively estimate that approximately 200 million additional people could be living in areas highly suitable for these three vector species by the end of the century, with new hotspots of human exposure emerging in Central and East Africa. Our results align with observed historical range shifts of Anopheles species but stand in contrast to earlier studies that have predicted climate change would have little effect on or even reduce malaria transmission. We find that climate change impacts on malaria vectors are highly species-specific, emphasizing the need for longitudinal field studies and integrated modeling approaches to address the ongoing redistribution of malaria vectors. As the world strives for malaria elimination amidst accelerating climate change, our study underscores the urgent need to adapt malaria control strategies to shifting vector distributions driven by environmental change.

Low-emissions, High Tensions: Social Media Groups and the Escalation of Climate Obstruction, Nadal, Environmental Communication

Backlash against climate policy is rare, but it is growing as policies become more present in everyday life, and resistance is becoming more confrontational. In the UK, this includes property destruction, non-compliance and death threats to public officials. This article explores the role of social media groups in the intensifying backlash through qualitative content analysis of posts in two of the UK’s largest public Facebook groups opposing low-emissions transport schemes promoted as essential for reaching net zero and tackling the climate crisis. Social media is now widely recognized as a key channel for contrarian claims, but diffusion models often still assume one-way flow from elites to the public, overlooking how claims also spread across social media groups via sharing, amplification and users generating evidence to fit frames supplied by organized denial. Although a direct link to offline activity cannot be drawn, the article shows how these groups help legitimize and motivate hostile behavior by glorifying saboteurs as heroes and discrediting policy proponents through dehumanizing language. Misinformation matters, though less by fueling opposition than by muddying policy debate and preventing policies from being judged on their merits. The findings offer insight into the changing nature of climate obstruction, with implications for climate engagement and misinformation response.

From this week's government/NGO section:

U.S. Climate Litigation During the Biden Years, Margaret Barry, (Sabin Center for Climate Change Law

Using cases collected in the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law’s Climate Litigation Database, the author analyzes the 630 climate change lawsuits filed in United States courts while President Joseph R. Biden was in office. During the Biden administration, the federal government reversed course on the first Trump administration’s climate deregulation and embarked on a “whole-of-government approach to combatting the climate crisis.” Many states and municipalities pursued their own efforts to mitigate and prepare for climate change, while other states undertook climate deregulatory efforts. During the four years of the Biden administration, many areas of the U.S. experienced disasters linked to and intensified by climate change, including hurricanes, extreme heat, and wildfires. This report assesses characteristics of the climate cases filed in federal and state courts during this time period, with these policies and climate events as their backdrop and subject matter. The author’s analysis does not assess the outcomes of these cases, many of which remain pending. Instead the report distills elements of these cases: what goals the litigation aimed to achieve, who the parties were, and the underlying subject matter and substantive law. The analysis — which builds on the Sabin Center’s reports on climate litigation during the first Trump administration — provides a quantitative overview of these characteristics of climate litigation. The author concludes with a discussion of how the trends in U.S. climate litigation may be evolving during the second Trump administration as the U.S. federal government once again reverses course on its climate agenda.

Who Bears the Burden of Climate Inaction?, Clausing et al., Brookings Papers on Economic Activity

Climate change is already increasing temperatures and raising the frequency of natural disasters in the United States. The authors examine several major vectors through which climate change affects U.S. households, including cost increases associated with home insurance claims and increased cooling, as well as sources of increased mortality. Although they consider only a subset of climate costs over recent decades, they find an aggregate annual cost averaging between $400 and $900 per household; in 10 percent of counties, costs exceed $1,300 per household. Costs vary significantly by geography, with the largest costs occurring in some western regions of the United States, the Gulf Coast, and Florida. Climate costs also typically disproportionately burden lower income households. They suggest the importance of research that looks beyond rising temperatures to extreme weather events; so far, natural disasters account for the bulk of the burden of climate change in the United States.

110 articles in 59 journals by 706 contributing authors

Physical science of climate change, effects

Changes in persistent anticyclonic circulation across Eurasian continent and its linkage with extreme heatwaves, Tong et al., Global and Planetary Change 10.1016/j.gloplacha.2025.105183

Conditions for instability in the climate–carbon cycle system, Clarke et al., Earth System Dynamics Open Access 10.5194/esd-16-2087-2025

Read more...

0 comments

Posted on 3 December 2025 by Guest Author

This video includes personal musings and conclusions of the creators and climate scientists Dr. Adam Levy and Dr Ella Gilbert. It is presented to our readers as an informed perspective. Please see video description for references (if any).

Video description

Ten years ago today, world leaders met to agree a plan to finally solve climate change. This was COP21, which led to the historical Paris Climate Agreement. But did the Paris Agreement actually achieve anything? After all, ten years on, we're emitting more than ever. But lots has changed in all this time. So in this video ?@ClimateAdam? & ?@DrGilbz? sit down and discuss what Paris did and didn't achieve for our planet, and what we can expect from the future of climate change.

Support ClimateAdam on patreon: https://patreon.com/climateadam

Support Dr Gilbz on patreon: https://www.patreon.com/cw/Dr_Gilbz

Read more...

0 comments

Posted on 2 December 2025 by Sue Bin Park

Skeptical Science is partnering with Gigafact to produce fact briefs — bite-sized fact checks of trending claims. You can submit claims you think need checking via the tipline. Skeptical Science is partnering with Gigafact to produce fact briefs — bite-sized fact checks of trending claims. You can submit claims you think need checking via the tipline.

Does the recent slowdown in Arctic sea-ice extent loss disprove human-caused warming?

The recent pause in Arctic sea-ice loss is natural variability on top of a long-term, human-driven decline. The recent pause in Arctic sea-ice loss is natural variability on top of a long-term, human-driven decline.

Arctic sea ice naturally expands in winter and contracts in summer, but satellite records since the late 1970s show a steep multi-decade decline in the yearly minimum of sea ice. Short-term fluctuations such as changes in ocean currents and regional weather can temporarily slow or accelerate melt, but cannot reverse the overall downward trajectory.

Although the record low minimum ice extent occurred in 2012, 2025 still ranked among the ten lowest years on record, consistent with warming driven by human greenhouse gas emissions. Recent climate modeling shows that multi-year pauses can occur during long-term decline. The recent slowdown is indicative of natural variability, not evidence against global warming.

The Arctic continues to lose sea ice over time, and human-caused warming remains the primary driver.

Go to full rebuttal on Skeptical Science or to the fact brief on Gigafact

This fact brief is responsive to quotes such as this one.

Sources

NASA World of Change: Arctic Sea Ice

NASA Arctic Sea Ice Minimum Extent - Earth Indicator

Polar Bears International Why has the Arctic sea ice minimum not set a new record in over 10 years?

Geophysical Research Letters Minimal Arctic Sea Ice Loss in the Last 20 Years, Consistent With Internal Climate Variability

Please use this form to provide feedback about this fact brief. This will help us to better gauge its impact and usability. Thank you!

Read more...

0 comments

Posted on 1 December 2025 by Guest Author

This article by Calum Lister Matheson, Associate Professor of Communication, University of Pittsburgh is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Contrails have a simple explanation, but not everyone wants to believe it. AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster Calum Lister Matheson, University of Pittsburgh Contrails have a simple explanation, but not everyone wants to believe it. AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster Calum Lister Matheson, University of Pittsburgh

Everyone has looked up at the clouds and seen faces, animals, objects. Human brains are hardwired for this kind of whimsy. But some people – perhaps a surprising number – look to the sky and see government plots and wicked deeds written there. Conspiracy theorists say that contrails – long streaks of condensation left by aircraft – are actually chemtrails, clouds of chemical or biological agents dumped on the unsuspecting public for nefarious purposes. Different motives are ascribed, from weather control to mass poisoning.

The chemtrails theory has circulated since 1996, when conspiracy theorists misinterpreted a U.S. Air Force research paper about weather modification, a valid topic of research. Social media and conservative news outlets have since magnified the conspiracy theory. One recent study notes that X, formerly Twitter, is a particularly active node of this “broad online community of conspiracy.”

I’m a communications researcher who studies conspiracy theories. The thoroughly debunked chemtrails theory provides a textbook example of how conspiracy theories work.

Boosted into the stratosphere

Conservative pundit Tucker Carlson, whose podcast averages over a million viewers per episode, recently interviewed Dane Wigington, a longtime opponent of what he calls “geoengineering.” While the interview has been extensively discredited and mocked in other media coverage, it is only one example of the spike in chemtrail belief.

Although chemtrail belief spans the political spectrum, it is particularly evident in Republican circles. U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has professed his support for the theory. U.S. Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene of Georgia has written legislation to ban chemical weather control, and many state legislatures have done the same.

Online influencers with millions of followers have promoted what was once a fringe theory to a large audience. It finds a ready audience among climate change deniers and anti-deep state agitators who fear government mind control.

Read more...

7 comments

|

|

The Consensus Project Website

THE ESCALATOR

(free to republish)

|

![]() Skeptical Science is partnering with Gigafact to produce fact briefs — bite-sized fact checks of trending claims. You can submit claims you think need checking via the tipline.

Skeptical Science is partnering with Gigafact to produce fact briefs — bite-sized fact checks of trending claims. You can submit claims you think need checking via the tipline. Electromagnetic fields from solar farms are far too weak to harm human health and fall well within accepted safety limits for exposure.

Electromagnetic fields from solar farms are far too weak to harm human health and fall well within accepted safety limits for exposure.

![]() Skeptical Science is partnering with Gigafact to produce fact briefs — bite-sized fact checks of trending claims. You can submit claims you think need checking via the tipline.

Skeptical Science is partnering with Gigafact to produce fact briefs — bite-sized fact checks of trending claims. You can submit claims you think need checking via the tipline. The recent pause in Arctic sea-ice loss is natural variability on top of a long-term, human-driven decline.

The recent pause in Arctic sea-ice loss is natural variability on top of a long-term, human-driven decline. Contrails have a simple explanation, but not everyone wants to believe it. AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster Calum Lister Matheson, University of Pittsburgh

Contrails have a simple explanation, but not everyone wants to believe it. AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster Calum Lister Matheson, University of Pittsburgh

Arguments

Arguments