My AGU talk on tackling climate myths in a free online course

Posted on 20 December 2014 by John Cook

This post is based on an invited presentation I gave at the 2014 American Geophysical Union Fall Meeting in San Francisco. The talk was titled Applying Agnotology Based Learning in a MOOC to Counter Climate Misconceptions. In it, I explained the approach taken in our upcoming MOOC (Massive Open Online Course) titled Making Sense of Climate Science Denial.

The slides for my talk are available in PDF form.

For the last few years, I’ve been talking to people about agnotology-based learning. Usually they blink or stare at me with blank eyes, responding with “agno-what now?” I explain that agnotology is the study of how and why we don’t know things, coming from the word agnostic. For example, studying the negative influence of misinformation about climate science.

In 2009, Dan Bedford coined the term “agnotology-based learning”. I met Dan a few years ago at a previous AGU Fall Meeting. We got on famously, sharing similar attitudes to climate communication and how to address misinformation. I was especially impressed with his approach to teaching climate science by debunking myths. As well as teach the scientific concepts, this approach also equipped the students with the critical thinking skills needed to identify the misleading techniques in misinformation.

In 2009, Dan Bedford coined the term “agnotology-based learning”. I met Dan a few years ago at a previous AGU Fall Meeting. We got on famously, sharing similar attitudes to climate communication and how to address misinformation. I was especially impressed with his approach to teaching climate science by debunking myths. As well as teach the scientific concepts, this approach also equipped the students with the critical thinking skills needed to identify the misleading techniques in misinformation.

Since then, I’ve continued to investigate agnotology-based learning, even co-authoring a paper in the Journal of Geoscience Education with Dan and Scott Mandia. When I began developing a MOOC based on the agnotology-based learning approach, naturally I was keen for Dan to be involved. This week at AGU, we recorded Dan’s MOOC lecture. Some of the SkS team think I have a bit of a bromance going with Dan but I think it’s just a strong working relationship with a healthy dose of mutual appreciation!

Why is addressing misinformation important? This quote from Jonathan Osborne sums it up:

Comprehending why ideas are wrong matters as much as understanding why some ideas may be right.

Education isn’t just about downloading new information into student’s heads. We also need to correct misconceptions, which interfere with new learning. Some misconceptions are especially corrosive. For example, misperceptions about the scientific consensus on human-caused global warming can have flow-on effects such as lower acceptance that climate change is happening and decreased support for policies to mitigate global warming.

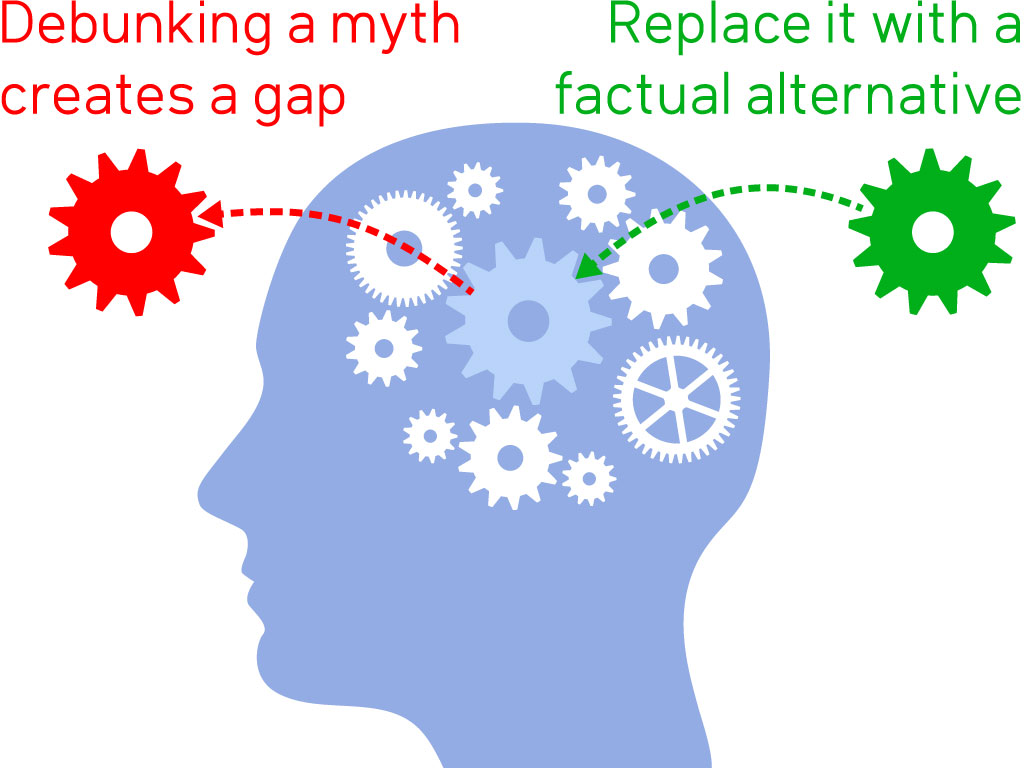

In order to effectively remove misconceptions, we need to understand what goes on under the hood when we debunk a myth. As people receive information, they build up a model of how the world works. All the cogs fit together to build an interlocking picture of how the world works.

If you tell someone that a part of their model is wrong, you create a gap in their mental model. But people prefer an complete, false model to an incomplete, accurate model. Just like a weed, the myth sneaks its way back into the model (psychologists call this the Continued Influence Effect).

So when you’re debunking a myth, it’s crucial that you fill the gap you created. Replace the myth with an alternative fact. All this psychological theory can be summed up concisely in the golden rule of debunking: fight sticky myths with stickier facts.

But that’s only half the job. As well as explain why the fact is true, you also need to explain why the myth is wrong. One way to do this is to explain the technique that the myth uses to distort the science. The techniques in most climate myths fall into one of the following five categories: Fake Experts, Logical Fallacies, Impossible Standards, Cherry Picking and Conspiracy Theories (I use the acronym FLICC to remember them).

Making Sense of Climate Science Denial debunks 50 of the most common climate myths, adopting the structure recommended by the psychological research. We start each debunking by explaining the science: the “factual alternative”. Then we explain how that science is distorted by the myth, examining the fallacy within the myth.

An important (and exciting) part of our MOOC will be interviews with some of the leading climate scientists from all over the world. We’ll feature explanations of the science and debunkings of the myths from the world’s greatest climate communicators. Richard Alley’s response to the “scientists are in it for the money” myth was such an extraordinary, sticky debunking, all I could say in response was “wow!”

As well as learn about climate change, we also examine how people think about climate change. Understanding the psychology of science denial is crucial to understanding why human-caused global warming, having achieved 97% consensus among climate scientists, is still a public controversy. Another important part of this story is the role that the Merchants of Doubt play, as explained by Naomi Oreskes.

And lastly, here’s a photo from our interview with Katharine Hayhoe, who was recently named one of Time Magazine's 100 most influential people, which always puts a smile on my face!

You can sign up free for our MOOC now (it launches in April 2015) at http://sks.to/denial101x.

Arguments

Arguments

I wonder if you're familiar with the work of Derek Muller; he did a PhD on how to teach physics. Your approach reminded me of his work, but watch for yourself:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AcX3IW00nuk

[PS] Fixed link

Yes, I have seen his work and watched his online talks (which are very good). We discussed interviewing him when we were at UNSW interviewing climate scientists but apparently he's abroad at the moment.

@bouke Thanks for the link. I had not seen that TED Ed talk, but I had seen D. Muller's video "Khan Academy and the Effectiveness of Science Videos" at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eVtCO84MDj8, which presents basically the same message, and I downloaded his thesis to read from the link in the YouTube video description. "Start with the misconception." People don't learn from being told; they learn from thinking (mental effort).

I watched the Muller video and it reminded me of this book:

Thinking Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman

Kahneman is an Israeli psychologist and Professor at Yale who won a Nobel Prize in Economics. The book is about what he calls Fast Thinking ("heuristics" or short cuts), and Slow Thinking which is more logical but mentally draining and demanding, but more likely to give right answers.

Fast Thinking has its place in time of crisis "fight or flight", but as humans we over-use it in a lazy fashion.

It seems to me Miller is saying that to teach physics, or probably any science, you need to engage Slow Thinking. Bit off-topic, but you might find Kahneman's book enlightening, John, if you have not already read it.

Shoyemore: am very familiar with Kahneman's fast and slow thinking, which is extremely relevant to how people think about climate change. Very insightful and influential work.

BTW, I've uploaded the slides for my talk in PDF form (link at the top of the OP).

Unfortunately, denials abound in this arena. Would you be tackling denials other than the denial of anthropogenic climate change existence in the course? For instance, please see, e.g.,

http://www.resilience.org/stories/2014-11-26/six-myths-about-climate-change-that-liberals-rarely-question

[PS] Fixed link

saileshrao:

The course is concerned with the rejection of the physical science behind climate change. There will be some commentary on the relationship between political orientation and people's willingness to accept the science of climate, but we will not be focussing on solutions or policy questions.

To be sure there's plenty of dispute and misconceptions about solutions and a continuing conversation about policy is necessary. However, most of the disagreements that exist on policy do not fit easily into the myth/fact framework that we will be adopting for this course. Much of the dispute in this area centres around values and culture, as opposed to the reliable knowledge that emerges from the physical sciences.

Learning the best way to help those who are inclined to want to 'better understand what is going on' to actually better understand an issue is indeed important. The more difficult task is effectively addressing those who are inclined not to want to better understand what is going on.

As an engineer with an MBA I have dealt with many people, including technically knowledgeable people, who will listen to the presentation of a detailed explanation on an issue, not just climate science issues, and at the end simply say they are not convinced. In some cases they say they need more proof that what they would prefer to believe is wrong. Usually, the motivation for their preferred belief is that it would be more beneficial for them (easier quicker cheaper) if they could stick with what they prefer to believe.

So far, I have found the only real effective way to deal with such people is to not allow them to do what they believe they should be allowed to do. As a Professional Engineer in Canada I have that authority and responsibility. However, the ones wanting to believe what they prefer can shop around for a different Professional who will support their beliefs. Sound familiar? Unsafe practice by a Professional Engineer in Canada can lead to them having their registration as Professional cancelled.

So it would seem that, in addition to helping others better understand, there needs to be effective mechanisms to cancel the purported legitimacy of those who try to maintain unjustified beliefs. That does not really seem to be something that scientists can do effectively. It requires sociopolitical leadership that is genuinely interested in developing a better future. That is hard to find in a socioeconomic system that promotes the pursuit of personal desire any way it can be gotten away with. So the socioeconomic system focused on popularity and profitability that has no motivation to develop a sustainable constantly improving better future for all is the problem. That is what also needs to be challenged and changed.

Andy Skuce:

Indeed, Naomi Klein has advanced the view that much denial of climate change science is rooted in values and culture:

www.thenation.com/article/164497/capitalism-vs-climate#

Jonathan Kay of the National Post, a decidedly conservative publication, pretty much concurs here:

www.pressprogress.ca/en/post/national-post-editor-explains-why-many-his-colleagues-are-climate-change-deniers

SAILESHRAO

Nice link, especially para. 3 in it.

Once again, it brings us back to population numbers. I see no real virtue in espousing a hair shirt model for the future only to allow even higher numbers on the planet, necessitating an even hairier shirt.

S

[JH]

You are skating on the thin ice of sloganeering which is prohibited by the SkS Comments Policy.

Please note that posting comments here at SkS is a privilege, not a right. This privilege can be rescinded if the posting individual treats adherence to the Comments Policy as optional, rather than the mandatory condition of participating in this online forum.

Please take the time to review the policy and ensure future comments are in full compliance with it. Thanks for your understanding and compliance in this matter.

Wol,

Though total population numbers are a problem the real problem is the highest consuming higest impacting among the population.

This planet will potentially be habitable for several hundred million years. A smaller population of high consumption high impact humans would not be sustainable.

The required development is for the most fortunate to be the lowest impact on the planet living in totally sustainable ways helping the less fortunate develop to that higher-level of decent considerate living.

I disagree with the claim that that would require the most fortunate to live a 'hairshirt life'. Such a claim is a poor excuse for not requiring all of the most fortunate to behave better and all participate in the serious effort toward the development of a sustainable better future for all. And I would argue that it is not the responsibility of only the caring and considerate to try to overcome the unacceptable impacts of those who willfully choose not to care.

I wonder if Wol considers UK, German or NZ citizens to live a "hair-shirt" existance? These people all manage on less than 1/2 the energy per capita than the USA or Canada. The poor hair-shirted Swedes manage to get by on only 7tCo2/person compared to around 25 for US and Australia.

The Germans pay about 6 Eurocents/kWh as a Renewable Levy. With the average family of 4 having an annual consumption of less than 4,000 kWh, that's about 60 Euros per person per year. Is that really hair-shirt territory?

scaddenp @12, and Turboblocke @13, That, and all without three potentially game changing technologies which have popped up on the horison.

Closest to commercial development is the Isentropic pumped thermal energy storage, which potentially ends issues about off peak to peak load sharing meaning the primary argument against renewables is no longer valid.

In the five to ten year horizon is a development in wind turbine design that could reduce the cost of wind energy by a factor of three, making it far and away the cheapest energy source on levelized costs (although not necessarilly when combined with energy storage).

Finally, in the 15 - 20 year range (for commercial development) is Lockheed Martin's Fusion project, which could end all future concerns about renewable energy. Of course, there is quite a bit more ahead of that project than just engineering development, so Lockheed Martin could end up with a fizzler, or (more likely) an energy source with uncommercial levelized costs so I would not put all (or any, at this stage) of our eggs in that basket. But while such major firms are staking their reputation so publicly on the viability of the project, it is a bit absurd to go around saying the prospect of renewable energy in large amounts, cheaply is simply a myth.

It seems to me that when we debunk the myth of climate science denial, we must replace this with a factual alternative that is compatible with a minimally regulated socioeconomic system or else, the targeted people will continue to reject the climate science. To quote Jonathan Kay from the National Post,

""The people I work with at the National Post — because there are some colleagues I have who are what you may call 'climate change deniers' — generally the one universal aspect is that they tend to be right-wing in their thinking, they see market-based solutions as the solution to enriching our society in every respect and it bothers them, the idea that here's this problem that cannot be solved with unfettered industrial activity."

Given this, I can understand why Naomi Klein's progressive triumphalism frightens these people:

"Responding to climate change requires that we break every rule in the free-market playbook and that we do so with great urgency. We will need to rebuild the public sphere, reverse privatizations, relocalize large parts of economies, scale back overconsumption, bring back long-term planning, heavily regulate and tax corporations, maybe even nationalize some of them, cut military spending and recognize our debts to the global South."

That screams "big government" to them and frankly, to me, as well.

Well instead of denial that problem exists, what is needed then is for the right wing to come up with a solution that isnt "big goverment" - I looked for suggestions here. If the right cant do so, then it is admitting to believing in a failed political philosphy. I find resorting to denial rather than thinking of solutions irksome and unworthy of right-wing predecessors.

saileshrao@15,

When you say "we must replace this with a factual alternative that is compatible with a minimally regulated socioeconomic system", I will add that a minimally regulated socioeconomic system will only work if every individual in it wants 'the development of a sustainable better future for all' significantly more than they want a better present for themself.

If you are preferring all people to be 'free to do as they please', no need to bother themselves with better understanding the consequences of their actions and without any concern for the development of a sustainable better future for all then the obvious required action becomes 'effective regulation of the behaviour of those people who only care about their personal interests and allowing them to be free of the regulation when they change their attitude' by as small a government as it takes to keep the trouble-makers from making trouble.

Smaller government being sustainable requires everyone to care about everyone else, and actually requires everyone to care about all other life on this amazing planet, and most importantly it requires them all to care about the future they will never live in.

One Planet Only Forever:

Indeed, a sense of caring for all life, both present and future, would be a pre-condition for those who can overcome their denial of climate science. But in that vein, scientific denial is much more widespread than just in the right wing community.

An estimated 52% of all vertebrates in the wild have been killed off between 1970 and 2010 and yet our routine behaviors do not reflect that simple fact. Perhaps addressing such denial may be a much more effective use of the course than attempting to change right wing minds.

saileshrao,

I consider the development of a sustainable better future for all life to be the main objective of life. Therefore, all unacceptable behaviour is to be targetted for effective curtailing, no matter how popular or profitable. However, if the required actions were to be prioritized the following factors are main points to be considered:

It is pretty clear that curtailing the burning of buried hydrocarbons is at or near the top of each significant consideration. So it must be addressed, along with action against what you are referring to.

The trouble makers love to have their trouble making believed to be 'too valued to be curtailed'. It is clear that the failure of the current socioeconomic system to curtail unacceptable activity, its development of effective promotion of such activity, is what needs to change.

It is clear that the success of people who fight against 'developing and acting on the better understanding of what is going on' is what needs to be curtailed. No sustainable good thing has ever developed from the success of those type of people. They thrive on benefiting at the expense of others. Some even try to justify profiting from making trouble for others, especially future trouble, by comparing how much benefit they believe they would have to give up against how much trouble they believe they are creating for others and future generations.

"Perhaps addressing such denial may be a much more effective use of the course than attempting to change right wing minds."

Any course of action by a democratic government needs enough assent to retain voter loyalty. At the moment, right wing denial is a major road block to effective action.

(Reply to moderator: unable to cut and paste his comment.)

Reference my post about population numbers and the moderator's reply, it is probably time that I unsubscribed from this site.

It seems an entirely valid and logical point to make, that for example doubling a population and halving its consumption leaves, all else being equal, no difference in consumption or indeed emissions.

Added to that, it is just not conceivable that the third world will not aspire to a higher standard of living, with all the additional consumption / emissions this entails.

Several subsequent posts entirely miss my point. Of *course* I was not implying that we in the West have anything like a hair shirt existence. What I was, and am, saying is that a sustainable population on a planet is inextricably linked to its consumption pattern. If a population of say 2Bn on planet earth is sustainable at the West's current standard of living (remember, I am plucking figures out of the air here: it's the principle that concerns me) it follows that 4Bn should have half that standard, and so on.

At some point the numbers would then show that a certain population level would only be long term sustainable if we all went into subsistence mode. Hair shirt, if you like.

Ignoring this fundamental, Malthusian, fact makes the whole climate change issue a bit pointless in some respects - and even a bit like the deniers' argument that technology will somehow come up with a magical solution.

As a layman with an intense interest in the scientific method, an abhorrence of pseudo science and having followed the climate question for some forty years, I can only say that I find the moderator's put-down unhelpful to those who accept the case for AGW. If one is not to be allowed to question the basic parameters of the climate "debate" unless one is involved in one of the relevant sciences then please remove my name from those who can post.

[JH] Now you are skating on the thin ice of excessive repetition - which is also prohibited by the SkS Comments Policy. You have made your points. It is time for you to move on.

Wol - The UN figures we'll peak at about 10B near 2100, although I've seen estimates all low as 8.5B peaking in 2025 (based on dropping birth rates in China and elsewhere). There are multiple influences, from women's literacy to birth control to increasing city living rather than agricultural, but I suspect that population growth won't be our most limiting factor for the future.

Rather, limited energy availability and pollution (unless there are substantial increases in the rate of renewable energy adoption), water, and the effects of climate change on primary agricultural capacity - possibly declining below sustainable levels for even those projected populations. Those are, IMO, more pressing concerns.

Wol,

There are many people in the world who do not aspire to the Western consumption model. Have you ever spent time in the third world talking to people in their houses? I have spent hundreds of hours talking to people across the South Pacific. While they would like to have the goods westerners have, often they prefer to have less goods so that they can spend more time with their friends. Look at how much time off people have in Europe and Australia compared to the USA. The Europeans sacrifice a certain amount of consumption to obtain more time off. The real world situation is much more complicated than your description of everyone wants to consume more.

My wife and I are planning on downsizing our consumption by moving into a small boat to live. We will have less goods but much more time to visit friends. We prefer this lifestyle (given up while our children attended school) and would have downsized last year except for health issues with our daughter. There are advantages to having less. Don't believe all the advertisements you see on television.

I agree with Wol. His time here is probably best ended. I had a little difficulty not 'flaming' a reply to his input @10, a view he tries to justify @21 with the long-defunct theorising of Thomas Malthus and the naive observation that "it is just not conceivable that the third world will not aspire to a higher standard of living, with all the additional consumption / emissions this entails."

It's rather difficult to presently see a return to the imperial days of old as a template for AGW mitigation. Is there any logic whatever in sending off the 'gunboats' to confiscate all the mobile phones etc from the citizens of nations with below average wealth, given a fair proportion of those nations are in places over-run by pleasure-seeking tourists from the wealthier parts of the world. And to suggest advancement of such poorer societies should be stopped because the wealther part of the world is wrecking the global environment becomes eye-poppingly bad when it is remembered that the wealthier parts would not themselves be similarly constrained and further when the main damage of that environmental wrecking is being meted out on the areas of the world where predominantly society is poor.

So I agree with Wol. The debate he wants is not appropriate here, although I note that Wol @21 appears not to appreciate why.