Arguments

Arguments

Software

Software

Resources

Comments

Resources

Comments

The Consensus Project

The Consensus Project

Translations

Translations

About

Support

About

Support

Latest Posts

- Fact brief - Can nearby solar farms reduce property values?

- Sea otters are California’s climate heroes

- 2026 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming News Roundup #06

- Skeptical Science New Research for Week #6 2026

- The future of NCAR remains highly uncertain

- Fact brief - Can solar projects improve biodiversity?

- How the polar vortex and warm ocean intensified a major US winter storm

- 2026 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming News Roundup #05

- Help needed to get translations prepared for our website relaunch!

- Skeptical Science New Research for Week #5 2026

- Climate Variability Emerges as Both Risk and Opportunity for the Global Energy Transition

- Fact brief - Are solar projects hurting farmers and rural communities?

- Winter 2025-26 (finally) hits the U.S. with a vengeance

- 2026 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming News Roundup #04

- Skeptical Science New Research for Week #4 2026

- WMO confirms 2025 was one of warmest years on record

- Fact brief - Do solar panels release more emissions than burning fossil fuels?

- Keep it in the ground?

- 2026 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming News Roundup #03

- Skeptical Science New Research for Week #3 2026

- Climate Adam - Will 2026 Be The Hottest Year Ever Recorded?

- Fact brief - Does clearing trees for solar panels release more CO2 than the solar panels would prevent?

- Where things stand on climate change in 2026

- 2026 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming News Roundup #02

- Skeptical Science New Research for Week #2 2026

- UK renewables enjoy record year in 2025 – but gas power still rises

- Six climate stories that inspired us in 2025

- How to steer EVs towards the road of ‘mass adoption’

- 2026 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming News Roundup #01

- Skeptical Science New Research for Week #1 2026

Archived Rebuttal

This is the archived Intermediate rebuttal to the climate myth "Solar projects will hurt farmers and rural communities". Click here to view the latest rebuttal.

What the science says...

|

Solar deployment would utilize a relatively small percentage of U.S. land when compared to the land currently being used for agriculture. |

Ambitious solar deployment would utilize a relatively small percentage of U.S. land when compared to the land currently being used for agriculture. The Department of Energy estimated that total U.S. solar development would take up roughly 10.3 million acres in a scenario in which cumulative solar deployment reaches 1,050–1,570 GW by 2050, the highest land-use scenario that DOE assessed in its 2021 Solar Futures Study1. If all 10.3 million acres of solar farms were sited on farmland, they would occupy only 1.15% of the 895,300,000 acres of U.S. farmland as of 20212. However, many of these projects will not be located on farmland.

Furthermore, solar arrays can be designed to allow, and even enhance, continued agricultural production on site. This practice, known as agrivoltaics, provides numerous benefits to farmers and rural communities, especially in hot or dry climates3. Agrivoltaics allow farmers to grow crops and even to graze livestock such as sheep beneath or between rows of solar panels4 (also Adeh et al. 2019). When mounted above crops and vegetation, solar panels can provide beneficial shade during the day (Williams et al. 2023). Multiple studies have shown that these conditions can enhance a farm’s productivity and efficiency (Aroca-Delgado et al. 2018). One study found, for example, that "lettuces can maintain relatively high yields under PV" because of their capacity to calibrate "leaf area to light availability" (Marrou et al. 2013). Extra shading from solar panels also reduces evaporation, thereby reducing water usage for crops by around 14-29%, depending on the level of shade (Dinesh & Pearce 2016). Reduced evaporation from solar installations can likewise mitigate soil erosion. Solar farms can also create refuge habitats for endangered pollinator species, further boosting crop yields while supporting native wild species5. Overall, agrivoltaics can increase the economic value of the average farm by over 30%, while increasing annual income by about 8%. Farmers in other countries have begun implementing agrivoltaic systems (Tajima & Iida 2021). As of March 2019, Japan had 1,992 agrivoltaic farms, growing over 120 different crops while simultaneously generating 500,000 to 600,000 MWh of energy6.

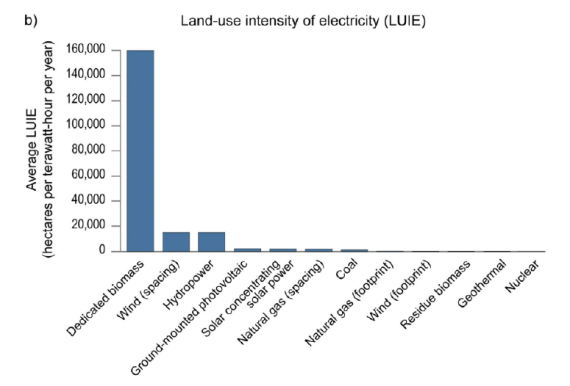

Furthermore, the argument that solar development will imperil the food supply is belied by the fact that tens of millions of acres of farmland are currently being used to grow crops for other purposes, such as the production of corn ethanol. Currently, roughly 90 million acres of agricultural land in the United States is dedicated to corn, with nearly 45% of that corn being used for ethanol production7. Solar energy could provide a significantly more efficient use of the same land. Corn-derived ethanol used to power internal combustion engines has been calculated to require between 63 and 197 times more land than solar PV powering electric vehicles to achieve the same number of transportation miles8. If converted to electricity to power electric vehicles, ethanol would still need roughly 32 times more land than solar PV to achieve the same number of transportation miles. And even when accounting for other energy by-products of ethanol production, solar PV produces between 14 and 17 times more gross energy per acre than corn. The figure below contrasts the land use requirements of solar PV with dedicated biomass and other energy sources. Whereas dedicated biomass consumes an average of 160,000 hectares of land per terawatt-hour per year, ground-mounted solar PV consumes an average of 2,100 (Lovering et al. 2022).

Figure 4: Average land-use intensity of electricity, measured in hectares per terawatt-hour per year. Source: U.S. Global Change Research Program (visualizing data from Jessica Lovering et al. 2022).

Finally, while solar installations, like any infrastructure projects, will inevitably have some adverse impacts, the failure to build the infrastructure necessary to avoid climate change poses a far more severe threat to agricultural production. Climate change already harms food production across the country and globe through extreme weather events, weather instability, and water scarcity9. The most recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report forecasts that climate change will cause up to 80 million additional people to be at risk of hunger by 205010. A 2019 IPCC report forecasted up to 29% price increases for cereal grains by 2050 due to climate change11. These price increases would strain consumers globally, while also producing uneven regional effects. Moreover, while higher carbon dioxide levels may initially increase yield for certain crops at lower temperature increases, these crops will likely provide lower nutritional quality. For example, wheat grown at 546–586 parts per million (ppm) CO2 has a 5.9–12.7% lower concentration of protein, 3.7–6.5% lower concentration of zinc, and 5.2–7.5% lower concentration of iron. Distributions of pests and diseases will also change, harming agricultural production in many regions. Such impacts will only intensify for as long as we continue to burn fossil fuels12.

Footnotes:

[1] U.S. Dep’t. Energy Solar Energy Technologies Office, Solar Futures Study, U.S. Dep’t. Energy Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy, at vi, 179 (Sep. 2021)

[2] U.S. Dep’t. of Agriculture, Farms and Land in Farms: 2021 Summary, 4 (Feb. 2022)

[3] Eric Larson et al., Net-Zero American: Potential Pathways, Infrastructure, and Impacts: Final Report, Princeton University, 247 (Oct. 29, 2021)

[4] Michael Nuckols, Considerations when leasing agricultural lands to solar developers, Cornell Small Farms (Apr. 6, 2020)

[5] Empowering Biodiversity on Solar Farms, University of Georgia College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, 2020

[6] This is enough energy to power roughly 50,000 American households. U.S. Energy Information Admin., Use of energy explained: Energy use in homes (last visited March 25, 2024)

[7] Feed Grains Sector at a Glance, U.S. Dep’t of Agriculture (last updated Dec. 21, 2023)

[8] Paul Mathewson & Nicholas Bosch, Corn Ethanol vs. Solar: Land Use Comparison at 1 (Clean Wisconsin 2023)

[9] Alisher Mirzabaev et al. (2023), Severe climate change risks to food security and nutrition, 39 Climate Risk Management 100473, 3, (“Adverse consequences are already occurring, and the chances of their exacerbation under climate change are high”); Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Climate Change and Food Security: Risks and Responses at ox-xii (2015); Agriculture and Climate, U.S. Env’t. Prot. Agency, (last visited March 25, 2024); Laura Reiley & Kadir van Lohuizen, Climate change is pushing American farmers to confront what’s next, Wash. Post, Nov. 10, 2023

[10] IPCC, Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability (2022), 717

[11] Chiekh Mbow et al., Food Security, in Climate Change and Land: an IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gases fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems, Exec. Summary, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2019).

[12] Causes and Effects of Climate Change, United Nations (last visited March 25, 2024).

This rebuttal is based on the report "Rebutting 33 False Claims About Solar, Wind, and Electric Vehicles" written by Matthew Eisenson, Jacob Elkin, Andy Fitch, Matthew Ard, Kaya Sittinger & Samuel Lavine and published by the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia Law School in 2024.

Updated on 2024-10-05 by SkS-Team.

THE ESCALATOR

(free to republish)