Climate change science comeback strategies

Posted on 8 August 2018 by Guest Author

This is a re-post from Yale Climate Connections by Karin Kirk

Credit: Image by Karin Kirk.

Credit: Image by Karin Kirk.

Staircase wit. L’esprit de l’escalier. It’s the way the perfect response in an uncomfortable conversation comes cruelly late, occurring only after the crux moment has long since passed, and you’re descending the stairs on your way home.

Why didn’t I think of that? you ask, kicking yourself for temporarily forgetting how carbon isotopes show that fossil fuels are indeed the source of the CO2 buildup in the atmosphere.

As the American culture war flares up like a SoCal heat wave, many feel understandably helpless watching misinformation accelerate throughout society. But even as you hit “enter” on a witty post correcting the spelling and grammar of someone who suggests scientists are incompetent, at some level you probably know this doesn’t improve the situation. Lobbing talking points back and forth typically only entrenches deeply held positions, a process known as belief polarization.

Want to see some expert comeback strategies for discussing #climatechange with a doubter?CLICK TO TWEET

So how then, to respond? Do you nod, smile, and walk away with clenched teeth? Do you whip out your smartphone and wave around graphs of ice core data?

Here are four strategies, each from a distinctly different point of view, each penned by an expert, each useful in either a face-to-face conversation on an online chat. The first lesson is this: have a conscious strategy, rather than a knee-jerk response. Think about where you want to go and what your goals are. And if your aim is to simply make the other person feel bad or look bad, then maybe reconsider if that’s helpful to either of you.

Let’s start with one of the most common climate contrarian remarks of all. One we’ve all heard many times: but the climate has changed before!

This is a modified version from a commenter on a government science agency Facebook page.

This is a modified version from a commenter on a government science agency Facebook page.

Strategy #1 – Correct the science

At its core, climate change is a scientific topic, although the controversy around it is largely pinned to ideology, rather than to scientific acumen. Nonetheless, a healthy dose of science is rarely a bad idea, as long as it’s delivered in a constructive manner. Remember, climate contrarians who have changed their minds have credited science more than any other factor.

Richard Alley, a widely respected climate scientist and communicator, host and author of the PBS documentary and companion book, Earth – The Operators’ Manual, and presenter of countless standing-room-only scientific talks, offers his scientific debrief of this common contrarian talking point.

Alley continues with his explanation, noting, “In certain settings, experts have some expectation that they will be allowed to make a long enough statement to summarize the knowledge on which they are expert.”

The savvy communicator, Alley knows that even the best science can fall flat without a personal connection. “Responses must be tailored to the person or persons in the discussion, their demeanor, and much more.” And even fabulous lecturers know that a conversation is more effective than a lecture. Alley looks for a fruitful avenue, “Is there a hint of a question … that could be used to open the discussion?”

Strategy #2 – Expose the myth, misinformation, or fallacy

Few may be surprised that most attempts to undermine climate science hinge on some type of misinformation. Cherry-picked data, fake experts, and conspiracy theories are well-worn hallmarks of contrarian rhetoric.

John Cook, founder of Skeptical Science and now a research assistant professor at the Center for Climate Change Communication at George Mason University, has extensive experience unraveling climate denial. Cook’s work has found that a sort of “inoculation” can help with climate misinformation. In other words, if people are exposed to the techniques commonly used in misinformation, they become more resistant to being misled when in the future they encounter bogus information.

So Cook’s response to the example comment is simple. He points directly to the logical fallacy at the heart of the myth, and uses an easy example to illustrate that the statement can’t be correct.

Credit: John Cook.

Cognitive science suggests that lengthy, complex information is not as memorable as short, sweet takeaways. Cook uses cartoons and analogies to help message resonate.

Cook explains, “The beauty of this type of response is that by addressing faulty logic, you can demonstrate that an argument is false without having to get bogged down in complicated scientific explanations.” He adds, “Although as a science communicator, I’m always keen to explain the science whenever I get the chance.”

Although it’s tempting to be smug when you feel facts are on your side, that’s unlikely to buy you traction. “Discuss the topic with respect, try to understand their thinking and how they came to their position,” advises Cook. And even more importantly, “Recognize that most people who use this argument are also victims of misinformation.”

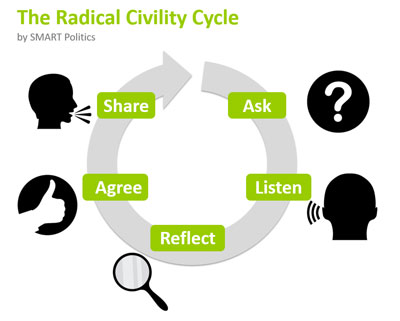

Strategy #3 – Engage in dialogue

One of the hardest tasks when faced with someone whose opinions clash with yours is to take a deep breath and do the unthinkable: listen.

Credit: Image by Karin Kirk.

Karin Tamerius, M.D., founder and managing director at Smart Politics, is trained in both psychiatry and political psychology. (Could there be a better preparation to understand today’s politics?)

Tamerius innovated an approach termed Radical Civility, which starts off by asking questions and actually listening to the answers. Radical, indeed.

Note how she starts off by agreeing with the commenter, and then asks a probing question.

“This seems to be a person who cares about and believes in science,” observes Tamerius. “For that reason, they are likely to be responsive to an inquiry about how climate science works.”

The Radical Civility Cycle is not a one-and-done approach. It takes several rounds of questions to establish rapport and nudge the conversation toward a productive outcome. Tamerius illuminates her long-game strategy, “I would hope to learn everything this person knows about the history of non-man-made climate change. Then, once they feel fully heard, I would gently explore the ways in which climate change is different in the human era and how we know.”

In an era where arguing dominates much of our public discourse, this technique offers a refreshing alternative. “I’m trying to move the other person from an argumentative to a learning mindset,” Tamerius notes. “I want them to be motivated by curiosity rather than a desire to show they are ‘right.'”

Strategy #4 – Be persuasive

Scott Gruhn doesn’t have formal training in climate science or communications, but he demonstrates admirable skill in both arenas. Gruhn is a tireless, effective defender and explainer of climate science on Facebook. His persuasive posts routinely get people to soften their stance and consider evidence, and he’s even been able to usher a half dozen people to do a complete turnabout in their views.

Like Tamerius, Gruhn settles in for a protected exchange, and kicks things off by praising and respecting the point of view of the commenter.

Gruhn continues, often in a series of shorter posts rather than one encyclopedic and unnavigable post.

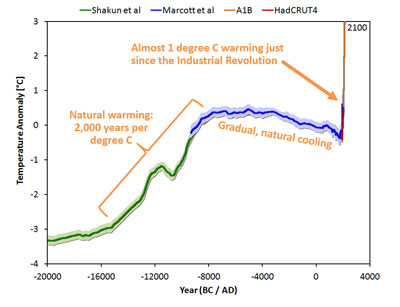

Base image used with permission.

Gruhn often peppers his responses with graphics, and steps readers through the science in a friendly manner. Here, he annotates a graph for easy comprehension.

Taking a cue from John Cook’s strategy, Gruhn makes a point to shine light on tactics used to spread misinformation. He offers these insights as advice to commenters, rather than beating them over the head with it.

Gruhn’s closing advice is something we can all take to heart, and ring ever more true as we unfriend, ignore, and turn our backs on people with different ideologies.

“Know the science. Know your values. Be caring. Don’t expect dramatic, visible changes of heart. Write for the undecided readers. Turn off the computer before your words get too sharp.”

The author is grateful to John Cook of George Mason University for his advice and recommendations on this project.

Arguments

Arguments

I think strategies 1 - 3 are excellent. Its hard to add anything.

I'm less persauded by strategy 4. It comes across as patronising, and I'm not sure you want to try to be the doubters "friend". But I think it does pay to talk freely in a humourous way, and anyway science is an adventure and exercise in discovery, and historical aspects are easy to grasp. Insults and ad hominems convince nobody.

Just some random thoughs on whats going on. Some denialists say provocative things like what about all this snow? but seem prepared to listen to arguments in an open minded way. I think they are secretely sitting on the fence, and say provocative things as a way of elicting the counter arguments as to why the world is in fact warming.

Of course some people have very rigid views about the science, and we see them just repeating the same things over and over. Some may be fronting lobby groups, some may not be. The political right has turned agw climate change into a sort of object of derision, and we know tribal affiliations mean subscribing to this view without question. You wont convince this lot, but that doesn't mean they won't support renewable energy. Texas has a lot of wind power I think, even although its Republican heartland.

But the acceptance of climate science has still improved in America, according to various polls, and so clearly views aren't entirely fixed with everyone. Imho the most likely reason is presentation of the facts about the issue, exposing the misleading nature of much denialism, and the continuing worsening weather.

Finally, an enlightening video => Scratching the 1.5°C Jazz

[DB] Reduced image widths breaking page formatting

Good graphical information. A picture paints 1000 words. Unfortunately plenty of people are simply not good at reading graphs.

A fascinating take on this whole subject is in the book Plows Plagues and Petroleum by Ruddiman. He shows pretty conclusively how we should have slid into a glacial period but the slide was slowed by the plow (releasing CO2 into the atmosphere) and rice cultivation (releasing methane) until, as we were finally almost at the threshold, plagues in Europe and North America resulted in massive forest growth and tipped us over the edge. This is visible around the high lands of Baffin Island (you have to read the book to see how). However CO2 was rising and tipped us back out of a glaciation. We have now pushed it way back despite the fact that we are at the bottom of the 22000 year cycle.

Another take on putting the recent warming in context, this time from Bruce Railsback's 'Fundamentals of Quaternary Science' at the University of Georgia:

Larger version here.

And this one, with the SLR curve from Shakun 2015 added in:

Regarding the first strategy, and addressing the "climate change has happened before without fossil fuels in the mix," I like to use the analogy that pretty much everyone can relate to: car troubles. If your car doesn't start, it could be for a whole host of reasons. This is because the car is a complex system with many inputs and outputs, so if the car is out of gas, has a dead battery, has run out of oil or coolant, or has a mechanical failure, it won't start. In a similar fashion, the complexity of global climate has many inputs and outputs, so that in the past orbital dynamics, volcanic output and natural emissions/absorption of greenhouse gases have driven the observed changes. This time, we've definitively isolated the release of greenhouse gases at a rate that is faster than the earth systems can absorb it as the source of the changes we are observing. You can ignore the science if you want, but it's kinda like ignoring your mechanic when he says that it's a dead battery and so you put more gas in the tank and expect the car to start. Furthermore, if your mechanic says that he replaced the battery so it should be fine and it still doesn't start, it's time to go to another mechanic.

Improving the awareness and understanding of more people regarding emergent truths is important. It is how humanity truly advances.

Achieving all of the comeback strategies would be the best way to sustainably change a person's mind, help the person choose to accept the improved awareness and understanding of climate science. And that will happen if they were interested in learning to improve their awareness and understanding of the emergent truths of climate science, no self interests keep them from improving their understanding.

However, it may also be helpful to test if the person being deal with is interested in improving their awareness and understanding, improving as a human being. Comments in public (including public forums) can benefit bystanders, even if they do not change the mind of the person they are directed at.

Pursuits of Human Improvement involve developing improved awareness and understanding based on the available evidence and choosing more helpful, less harmful, ways to act based on that constantly improved wisdom.

A Good way to test a person's interest in improving their humanity is bringing up the UN Sustainable Development Goals and seeing how they respond. If they say that they like any aspect of the goals I use that as my way in to a deeper discussion. All of the goals need to be achieved for any of the goals to actually be achieved. And it is easy to explain how more aggressive corrective Climate Action makes it easier to achieve almost any of the other goals (and that a lack of action makes it harder to achieve them).

For humanity to have the best possible future, Good Helpful Altruistic Reasoning has to govern and limit all human activity. It would be best if everyone self-governed responsibly.

Everyone can be helped to improve their way of thinking about things. But, those who resist improving their awareness and understanding need to be identified and be kept from significantly affecting things until their developed high degree of harmful selfishness is helpfully corrected to being more helpfully altruistic.

I think the following is a good way to make that point. It also addresses challenges about who decides what is good or acceptable. Many people mistakenly believe that any alternative opinion is 'equally valid - equally deserving of consideration'. That way of thinking leads to the belief that the emergent truths developed by improved awareness and understanding must be compromised 'out of consideration for people who prefer to believe other things'.

I propose two choices for determining if what human action is acceptable or desired, and if a preferred belief needs to be corrected.

A: Acceptable is - Doing no harm to others and not detrimental to developing a lasting improved future for humanity. Desired is - helping others and helping develop a sustainable future for humanity.

B: Allow some people to enjoy their lives more by doing things that are understandably detrimental to achieving A, either delaying A or actually causing harm to other humans, and causing harm to other life may be understood to be harming other humans, especially the way that extinction of life forms almost certainly harms the ability of a robust diversity of future humans to sustainably fit into a robust diversity of life.

A person who understands that A is the proper objective measure of acceptability and what should govern or limit desires can be helped to also understand the unacceptability of compromising A for B at any time in any way.

This would lead a person to be more open to improved awareness of climate science and the importance of achieving all of the Sustainable Development Goals, especially the climate action goals (the sooner the better for the future of humanity).

The major detractors of climate science try to prolong or increase the benefit that a portion of current day humanity can obtain from the burning of fossil fuels to the detriment of the entire future of humanity. They are not interested in increased awareness or understanding of the unacceptability of what they have developed a strong desire to personally benefit from. And they really dislike being corrected, or limited regarding their 'belief excused' actions.

A conversation that includes the consideration how to help develop a sustainable better future for humanity can improve the awareness and understanding of a bystander, even if the conversation does not change the mind of the person directly engaged.

If the conversation is private, no chance of bystanders learning from it, and I get a sense that the person does not care about the Sustainable Development Goals, I don't bother discussing the climate science. I briefly try to get them to change their mind regarding the future of humanity. And if that fails I express my disappointment about their lack of interest in becoming a more helpful person, and offer to help them if they are interested, then I move on.

This is similar to what I learned to do as an engineer. My objective was to help people achieve a better result. I learned to test how interested the people I was dealing with were to improving their awareness and understanding of proper (ethical) engineering. I learned to find out if they genuinely wanted the work done properly to protect the public and the environment from the potentially harmful consequences of the desires of people who want something more profitable (faster or cheaper), or if they were simply interested in trying to impress people who wanted more benefit by getting things done faster and cheaper in the hopes that they could make more money that way.