New study finds incredibly high carbon pollution costs – especially for the US and India

Posted on 1 October 2018 by dana1981

The social cost of carbon is a measure of the economic damages caused (via climate change) by each ton of carbon pollution that we produce today. It’s difficult to estimate because of physical, economic, and ethical uncertainties. For example, it’s difficult to predict exactly when various climate tipping points will be triggered, how much their damages will cost, and there’s also a question about how much we value the welfare of future generations (which is incorporated in the choice of ‘discount rate’).

In 2013, the Obama administration set the federal social cost of carbon estimate at $37 per ton of carbon dioxide (up from the previous estimate of $22). That was a conservative estimate – in recent years, research has pegged the value closer to $200 because recent research has shown that global warming slows economic growth, which makes it quite expensive. A majority of economists in a 2015 survey believed the federal estimate was too low, but Republicans have recently been trying to dramatically lower it anyway.

The Republican argument is twofold. First, that we should only consider domestic climate costs (the federal estimate is of global costs, because our carbon pollution doesn’t just hover in the air above America). Second, that instead of trying to stop climate change now, we should just save our money and let future generations pay for its costs (by using a high discount rate).

The social cost of carbon is much higher yet

A new study led by UC San Diego’s Katharine Ricke published in Nature Climate Change found that not only is the global social cost of carbon dramatically higher than the federal estimate – probably between $177 and $805 per ton, most likely $417 – but that the cost to America is around $50 per ton. That’s the second-highest in the world behind India’s $90, and is also higher than the current federal estimate for the global social cost of carbon.

That’s a remarkable conclusion worth repeating. Ricke’s team found that the cost of carbon pollution to just the United States is probably higher than its government’s current estimate of costs to the entire world. And the actual global cost is more than 10 times higher than the federal estimate. And yet Republican politicians think that estimate should be much lower.

The study

I asked Ricke to describe her team’s approach in this study:

To calculate social cost of carbon, you need to answer four questions in sequence:

1. How would the economy change with no climate change (including GHG emissions)?

2. How does the Earth system respond to emissions of carbon dioxide?

3. How does the economy respond to changes in the Earth system?

4. How should we value losses today vs. in (for example) 100 years?

The team answered these questions using four ‘modules’: a socio-economic module to answer the first question, a climate module to address the second, a damages module to investigate the third, and a discounting module to tackle the fourth.

Ricke further described the team’s approach in a ‘behind the paper’ article for Nature:

The idea was to combine an approach to analyzing the climate effect of a marginal emission of carbon dioxide that Ken Caldeira and I had recently developed, with a climate damages model described in what was then a working paper by Marshall Burke and collaborators. My co-author Massimo Tavoni pointed out that by combining these two tools, we could produce the first comprehensive, country-level estimates of the social cost of carbon.

The US is at the ideal economic temperature

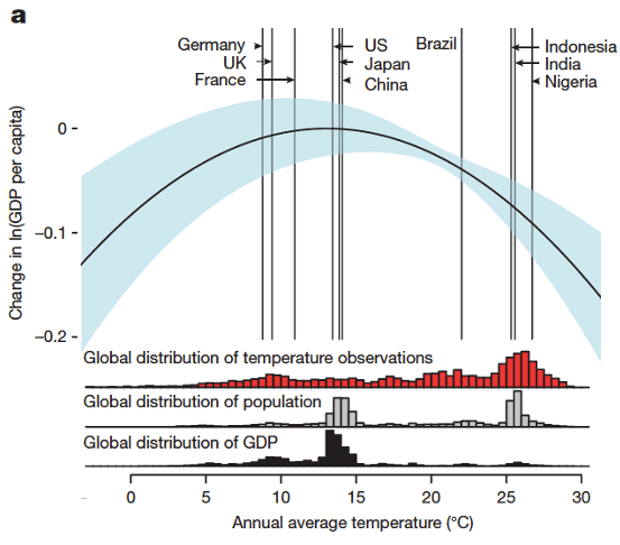

I wrote about the referenced Burke paper in 2015. That study detailed the relationship between a country’s average temperature and its per capita GDP, finding a sweet spot around 13°C (55°F). That’s the optimal temperature for human economic productivity. Economies in countries with lower average temperatures like Canada and Russia would benefit from additional warming, but it would slow economic growth for nations closer to the equator with hotter temperatures.

Global relationship between annual average temperature and change in log gross domestic product (GDP) per capita during 1960–2010 with 90% confidence interval. Illustration: Burke et al. (2015), Nature

The United States is currently right near the peak temperature, whereas many European countries like Germany, the UK, and France are 3–5°C cooler, and a bit below the ideal economic temperature. So, continued global warming is worse for the US economy than Europe’s.

China’s social cost of carbon is lower despite a similar temperature and GDP to America’s because its economy is growing fast, meaning that it would benefit from investing its money now rather than spending it on cutting carbon pollution, at least relative to a more developed country like the US. But China’s social cost of carbon is still about $26 per ton. India’s $90 is the highest because of its combination of a hot climate, high GDP (6th in the world), and anticipated continued growth leading to large future damages.

Arguments

Arguments

This is interesting, but economics is not the only measure of value. I would say the value of stopping global warming is priceless. Therefore, the correct price to put on carbon is that which does all it can to help stop global warming, which is to 100% eliminate GHG emissions from combustion of fossil fuels. We can discover that price by continually increasing the carbon price until there are no more such emissions, say a minimum increase of $10/tonne/year adjusted for inflation and if it turns out that is not working fast enough, rachet it up to a new minimum. Since the price is expected to go very high, it cannot be a tax, it must be revenue neutral. This is close to the proposal known as Carbon Fee and Dividend recommended by James Hansen and advocated by Citizens Climate Lobby (CCL). The Climate Leadership Council (CLC) backed by Exxon, Shell, BP, Total, GM, Exelon and a bevy of conservatives in the US also say they advocate Carbon Fee and Dividend but they want to roll back all regulations, whereas there are some perfectly good regulations like for corporate average fuel efficienty standards and methane inspection and fixing and possibly others that should stay and CLC, not to be confused with CCL, are wishy washy on price increases above 40$/ton (could that be because while it knocks out coal as a competitor it possibly leaves oil in still a not bad position for transportation and natural gas for building heating, industry and power generation - or am I being cynical?) a

Recommended supplemental reading:

Fighting climate change is too expensive because destroying the planet is cost-free, Opinion by Tom Toles, Washington Post, Oct 1, 2018