Why Greenland's ice loss matters

Posted on 27 May 2010 by John Cook

There are various stages of denial along the skeptic spectrum. The first stage is "It's not happening". In the case of the Greenland ice sheet, an early argument was that "Greenland can't be losing ice because it's gaining ice in the interior". However, a number of independent lines of evidence have all shown that overall, the Greenland ice sheet is losing ice. In fact, the rate of ice loss is accelerating. In light of this unequivocal evidence, many have moved onto the second stage, "okay, it's happening but it's not so bad. Greenland is losing 286 gigatonnes of ice per year? Big deal! There's around 3 million gigatonnes still remaining in the huge ice sheet. Take a chill pill, alarmist!"

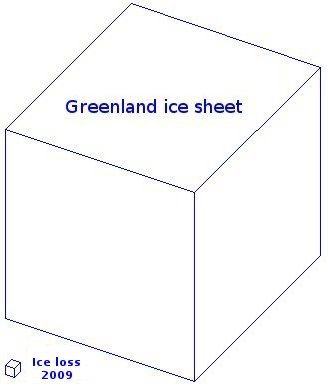

This view is articulated by Willis Eschenbach in On Being the Wrong Size (well, he didn't say to take a 'chill pill', that was creative licence on my part). Eschenbach argues that Greenland is losing about 0.007% of its total mass every year. At that rate, it will take 15,000 years to dissipate. Personally, I love a good visual so kudos must go to one of our regulars, Berényi Péter, who posted this picture in an earlier Skeptical Science comment, comparing 2009 ice loss to the total ice sheet:

The important point to remember here is that ice loss is accelerating. In 2002, the ice loss was 137 gigatonnes per year (Velicogna 2009). At that rate, the ice sheet would take nearly 22,000 years to dissipate. By 2009, this rate had more than doubled to 286 gigatonnes per year, reducing the ice sheet "lifetime" to 10,500 years. As the rate of ice loss increases, the ice sheet's lifetime is also diminishing.

So the crucial question is how will the Greenland ice sheet behave in the future? Extrapolating an accelerating curve into the future is always problematic. However, there are several different ways to approach the problem.

One method is to study the physics of glacier movements. One paper calculates glacier dynamics factoring Greenland's topography, the cross-sectional area of its glaciers and whether the bedrock is based below sea level (Pfeffer 2008). Including contributions from Greenland and Antarctica, the study estimates global sea level rise between 80 cm to 2 metres by 2100.

A semi-empirical technique looks at how sea level and global temperature have changed in the past (Vermeer 2009). Sea level change can then be expressed as a function of temperature change and future projections of global temperature can be used to simulate future sea levels. This method predicts global sea level rise of 75cm to 180cm by 2100.

Climate modelling of the Greenland ice sheet predicts eventual collapse of the Greenland ice sheet if CO2 levels go over 400 parts per million (ppm). We're currently at 392 ppm. At 400 ppm, they predict that over the next 400 years, the ice sheet will lose between 20 to 41% of its volume (). This is equivalent to roughly 1.4 to 2.8 metres of sea level rise just from Greenland.

Lastly, we learn much about how the Greenland ice sheet behaves by looking at sea level change in the past. The more optimistic IPCC emission scenarios predict warming of 1 to 2°C. The last time temperatures were this warm was 125,000 years ago. At this time, sea levels were over 6 metres higher than current levels (Kopp 2009). This tells us the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets are highly sensitive to sustained, warmer temperatures and are likely to contribute sea level rise measured in metres in future centuries.

So Willis Eschenbach and Berényi Péter do us a service in illustrating how much ice is still left in the Greenland ice sheet. This is a vivid reminder of Greenland's potential to contribute significantly to sea level rise in the future. And multiple lines of peer-reviewed evidence, both modelled and empirical, all paint a similar picture. The Greenland ice sheet is highly sensitive to warmer temperatures and is likely to contribute sea level rise in the order of metres over the next few centuries.

Arguments

Arguments

In this case, I think it's a reach to say Stone 2010 is just about modelling therefore its inappropriate to talk about the model results. While there is still much work to be done on modelling the Greenland ice sheet, does that mean we're not allowed to talk about the model results until they're perfect? In any case, I'm attempting to represent the paper as written, not the comments of that referree's comment. I will point out also that I chose to describe their best case scenario, not the worst case - a bit of IPCC-like conservatism on my part.

But the broader point here is that the Stone 2010 paper is just one result among many. There is also an empirical result (the paleoclimate study on over 6 metres sea level rise in the last interglacial), a semi-empirical result (mapping sea level rise to temperature to predict 75cm to 180cm by 2100. There's an alternative method of modelling glacier dynamics that finds sea level rise of 80 cm to 2 metres by 2100. These papers all use independent methods to arrive at the same conclusion - that Greenland is highly sensitive to sustained warmer temperatures and we can expect it to contribute significant sea level rise over this century and beyond.

So while I appreciate your feedback about Stone 2010 - especially the fact that it has yet to be approved of which I wasn't aware of - can I suggest you don't lose sight of the bigger picture and that you survey the full body of evidence before coming to any conclusions of where Greenland is headed.