Latest Posts

Archives

|

|

Explaining climate change science & rebutting global warming misinformation

Global warming is real and human-caused. It is leading to large-scale climate change. Under the guise of climate "skepticism", the public is bombarded with misinformation that casts doubt on the reality of human-caused global warming. This website gets skeptical about global warming "skepticism".

Our mission is simple: debunk climate misinformation by presenting peer-reviewed science and explaining the techniques of science denial, discourses of climate delay, and climate solutions denial.

Posted on 7 December 2025 by BaerbelW, Doug Bostrom

A listing of 28 news and opinion articles we found interesting and shared on social media during the past week: Sun, November 30, 2025 thru Sat, December 6, 2025.

Stories we promoted this week, by category:

Climate Change Impacts (8 articles)

- Where no one really dies One of the most wonderful people I've met as a climate journalist died this year. But Shelton Kokeok, like everyone in Shishmaref, lives on through his name. Basline on Substack, John D. Sutter, Nov 30, 2025.

- Will Glacier Melt Lead to Increased Seismic Activity in Mountain Regions? State of the Planet, Emily Cohen, Dec 01, 2025.

- In Burned Forests, the West`s Snowpack Is Melting Earlier As blazes expand to higher elevations, the impacts cascade downstream. Inside Climate News, Mitch Tobin, Dec 02, 2025.

- Global heating and other human activity are making Asia`s floods more lethal Much improved response systems are struggling to cope with ever more powerful and destructive storms The Guardian, Ajit Niranjan, Dec 02, 2025.

- COP30 Is Over. But for the World`s Most Vulnerable, the Crisis Is Ongoing. State of the Planet, Anyieth Philip Ayuen, Dec 04, 2025.

- An Alaskan Village Confronts Its Changing Climate: Rebuild or Relocate? After a devastating storm, the people who fled a remote coastal village face an existential question. New York Times, Scott Dance and Katie Basile, Dec 05, 2025.

- Climate change is boosting health care costs An online tool helps businesses figure out how much climate change could increase what they pay for their employees’ health care Yale Climate Connections, YCC Team, Dec 05, 2025.

- Climate change threatens Europe's remaining peatlands, study shows Phys.org, ERINN Innovation, Dec 06, 2025.

International Climate Conferences and Agreements (6 articles)

- Many Fighting Climate Change Worry They Are Losing the Information War Shifting politics, intensive lobbying and surging disinformation online have undermined international efforts to respond to the threat. New York Times, Lisa Friedman and Steven Lee Myers, Nov 30, 2025.

- Paris Climate Agreement At 10: Did It Do Anything? ClimateAdam & Dr Gilbz on Youtube, Adam Levy and Ella Gilbert, Nov 30, 2025.

- Are UN climate summits a waste of time? No, but they are in dire need of reform The Conversation, Arthur Wyns, Dec 01, 2025.

- `The dinosaurs didn`t know what was coming, but we do`: Marina Silva on what needs to follow Cop30 Exclusive: Brazil’s environment minister talks about climate inaction and the course we have to plot to save ourselves and the planet. The Guardian, Jonathan Watts, Dec 03, 2025.

- News roundup: COP30 wasn`t a complete failure Nuanced readings dig into what comes next for international climate politics and the people-powered movements pushing for meaningful solutions. Yale Climate Connections, SueEllen Campbell, Dec 03, 2025.

- Al Gore's case for optimism Gore talks to HEATED about COP30, the Gates memo, and why he thinks billionaires should face far more scrutiny in the climate fight. HEATED, Emily Atkin, Dec 04, 2025.

Read more...

0 comments

Posted on 4 December 2025 by Doug Bostrom, Marc Kodack

Open access notables

Bedrock uplift reduces Antarctic sea-level contribution over next centuries, van Calcar et al., Nature Communications

The contribution of the Antarctic Ice Sheet to barystatic sea-level rise could be as high as eight metres around 2300 but remains deeply uncertain. Ice sheet retreat causes bedrock uplift, which can exert a stabilising effect on the grounding line. Yet, sea-level projections exclude bedrock adjustment, use simplified Earth structures or omit the uncertainty in climate response and Earth structure. We show that the grounding line retreat is delayed by 50 to 130 years and the barystatic sea-level contribution reduced by 9–23% when the heterogeneity of the solid Earth is included in a coupled ice – bedrock model under different emission scenarios till 2500. The effect of the solid Earth feedback in ice sheet projections can be twice as large as the uncertainty due to differences between climate models. We emphasise that realistic Earth structures should be considered when projecting the Antarctic contribution to barystatic sea-level rise on centennial time scales.

Loss of vegetation functions during the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum, Rogger et al., Nature Communications

The Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM) around 56 million years ago was a 5–6°C global warming event that lasted for approximately 200 kyr. A warming-induced loss and a 70–100 kyr lagged recovery of biospheric carbon stocks was suggested to have contributed to the long duration of the climate perturbation. Here, we use a trait-based, eco-evolutionary vegetation model to test whether the PETM warming exceeded the adaptation capacity of vegetation systems, impacting the efficiency of terrestrial organic carbon sequestration and silicate weathering. Combined model simulations and vegetation reconstructions using PETM palynofloras suggest that warming-induced migration and evolutionary adaptation of vegetation were insufficient to prevent a widespread loss of productivity. We conclude that global warming of the magnitude as during the PETM could exceed the response capacity of vegetation systems and cause a long-lasting decline in the efficiency of vegetation-mediated climate regulation mechanisms.

Marine heatwave decimates fire coral populations in the Caribbean, Dell’Antonio et al., Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

Marine heatwaves (MHW) are common destructive events affecting coral reefs. After decades of degradation, the shallow reefs of the United States Virgin Islands have been depleted of scleractinian corals, leaving abundant colonies of the hydrozoan fire coral Millepora dominating the coral community. This dominance ended in 2024 after 84% of Millepora colonies over 43 km of shore were killed by a MHW that brought the hottest October in the 36 y since monitoring began. In August 2024, dead Millepora were rare on these reefs, but by March 2025, severe bleaching created a fire coral graveyard. Decimation of the fire coral biotope shows that these short-term coral winners are unlikely to be future reef builders.

Climate Change Favors African Malaria Vector Mosquitoes, van der Deure et al., Global Change Biology

Here, we for the first time estimate the future human exposure to each of six dominant African malaria vector species. Using an extensive mosquito observation dataset, robust species distribution modeling, and climate and land-use data, we investigate the climatic niches of six dominant African malaria vector species and map out their differing responses to climate and land use change across sub-Saharan Africa. Projections of future vector suitability identify three species that are likely to experience a substantial expansion of suitable habitat: Anopheles gambiae, Anopheles coluzzii, and Anopheles nili s.l. By combining these projections with human population density data, we conservatively estimate that approximately 200 million additional people could be living in areas highly suitable for these three vector species by the end of the century, with new hotspots of human exposure emerging in Central and East Africa. Our results align with observed historical range shifts of Anopheles species but stand in contrast to earlier studies that have predicted climate change would have little effect on or even reduce malaria transmission. We find that climate change impacts on malaria vectors are highly species-specific, emphasizing the need for longitudinal field studies and integrated modeling approaches to address the ongoing redistribution of malaria vectors. As the world strives for malaria elimination amidst accelerating climate change, our study underscores the urgent need to adapt malaria control strategies to shifting vector distributions driven by environmental change.

Low-emissions, High Tensions: Social Media Groups and the Escalation of Climate Obstruction, Nadal, Environmental Communication

Backlash against climate policy is rare, but it is growing as policies become more present in everyday life, and resistance is becoming more confrontational. In the UK, this includes property destruction, non-compliance and death threats to public officials. This article explores the role of social media groups in the intensifying backlash through qualitative content analysis of posts in two of the UK’s largest public Facebook groups opposing low-emissions transport schemes promoted as essential for reaching net zero and tackling the climate crisis. Social media is now widely recognized as a key channel for contrarian claims, but diffusion models often still assume one-way flow from elites to the public, overlooking how claims also spread across social media groups via sharing, amplification and users generating evidence to fit frames supplied by organized denial. Although a direct link to offline activity cannot be drawn, the article shows how these groups help legitimize and motivate hostile behavior by glorifying saboteurs as heroes and discrediting policy proponents through dehumanizing language. Misinformation matters, though less by fueling opposition than by muddying policy debate and preventing policies from being judged on their merits. The findings offer insight into the changing nature of climate obstruction, with implications for climate engagement and misinformation response.

From this week's government/NGO section:

U.S. Climate Litigation During the Biden Years, Margaret Barry, (Sabin Center for Climate Change Law

Using cases collected in the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law’s Climate Litigation Database, the author analyzes the 630 climate change lawsuits filed in United States courts while President Joseph R. Biden was in office. During the Biden administration, the federal government reversed course on the first Trump administration’s climate deregulation and embarked on a “whole-of-government approach to combatting the climate crisis.” Many states and municipalities pursued their own efforts to mitigate and prepare for climate change, while other states undertook climate deregulatory efforts. During the four years of the Biden administration, many areas of the U.S. experienced disasters linked to and intensified by climate change, including hurricanes, extreme heat, and wildfires. This report assesses characteristics of the climate cases filed in federal and state courts during this time period, with these policies and climate events as their backdrop and subject matter. The author’s analysis does not assess the outcomes of these cases, many of which remain pending. Instead the report distills elements of these cases: what goals the litigation aimed to achieve, who the parties were, and the underlying subject matter and substantive law. The analysis — which builds on the Sabin Center’s reports on climate litigation during the first Trump administration — provides a quantitative overview of these characteristics of climate litigation. The author concludes with a discussion of how the trends in U.S. climate litigation may be evolving during the second Trump administration as the U.S. federal government once again reverses course on its climate agenda.

Who Bears the Burden of Climate Inaction?, Clausing et al., Brookings Papers on Economic Activity

Climate change is already increasing temperatures and raising the frequency of natural disasters in the United States. The authors examine several major vectors through which climate change affects U.S. households, including cost increases associated with home insurance claims and increased cooling, as well as sources of increased mortality. Although they consider only a subset of climate costs over recent decades, they find an aggregate annual cost averaging between $400 and $900 per household; in 10 percent of counties, costs exceed $1,300 per household. Costs vary significantly by geography, with the largest costs occurring in some western regions of the United States, the Gulf Coast, and Florida. Climate costs also typically disproportionately burden lower income households. They suggest the importance of research that looks beyond rising temperatures to extreme weather events; so far, natural disasters account for the bulk of the burden of climate change in the United States.

110 articles in 59 journals by 706 contributing authors

Physical science of climate change, effects

Changes in persistent anticyclonic circulation across Eurasian continent and its linkage with extreme heatwaves, Tong et al., Global and Planetary Change 10.1016/j.gloplacha.2025.105183

Conditions for instability in the climate–carbon cycle system, Clarke et al., Earth System Dynamics Open Access 10.5194/esd-16-2087-2025

Read more...

0 comments

Posted on 3 December 2025 by Guest Author

This video includes personal musings and conclusions of the creators and climate scientists Dr. Adam Levy and Dr Ella Gilbert. It is presented to our readers as an informed perspective. Please see video description for references (if any).

Video description

Ten years ago today, world leaders met to agree a plan to finally solve climate change. This was COP21, which led to the historical Paris Climate Agreement. But did the Paris Agreement actually achieve anything? After all, ten years on, we're emitting more than ever. But lots has changed in all this time. So in this video ?@ClimateAdam? & ?@DrGilbz? sit down and discuss what Paris did and didn't achieve for our planet, and what we can expect from the future of climate change.

Support ClimateAdam on patreon: https://patreon.com/climateadam

Support Dr Gilbz on patreon: https://www.patreon.com/cw/Dr_Gilbz

Read more...

0 comments

Posted on 2 December 2025 by Sue Bin Park

Skeptical Science is partnering with Gigafact to produce fact briefs — bite-sized fact checks of trending claims. You can submit claims you think need checking via the tipline. Skeptical Science is partnering with Gigafact to produce fact briefs — bite-sized fact checks of trending claims. You can submit claims you think need checking via the tipline.

Does the recent slowdown in Arctic sea-ice extent loss disprove human-caused warming?

The recent pause in Arctic sea-ice loss is natural variability on top of a long-term, human-driven decline. The recent pause in Arctic sea-ice loss is natural variability on top of a long-term, human-driven decline.

Arctic sea ice naturally expands in winter and contracts in summer, but satellite records since the late 1970s show a steep multi-decade decline in the yearly minimum of sea ice. Short-term fluctuations such as changes in ocean currents and regional weather can temporarily slow or accelerate melt, but cannot reverse the overall downward trajectory.

Although the record low minimum ice extent occurred in 2012, 2025 still ranked among the ten lowest years on record, consistent with warming driven by human greenhouse gas emissions. Recent climate modeling shows that multi-year pauses can occur during long-term decline. The recent slowdown is indicative of natural variability, not evidence against global warming.

The Arctic continues to lose sea ice over time, and human-caused warming remains the primary driver.

Go to full rebuttal on Skeptical Science or to the fact brief on Gigafact

This fact brief is responsive to quotes such as this one.

Sources

NASA World of Change: Arctic Sea Ice

NASA Arctic Sea Ice Minimum Extent - Earth Indicator

Polar Bears International Why has the Arctic sea ice minimum not set a new record in over 10 years?

Geophysical Research Letters Minimal Arctic Sea Ice Loss in the Last 20 Years, Consistent With Internal Climate Variability

Please use this form to provide feedback about this fact brief. This will help us to better gauge its impact and usability. Thank you!

Read more...

0 comments

Posted on 1 December 2025 by Guest Author

This article by Calum Lister Matheson, Associate Professor of Communication, University of Pittsburgh is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Contrails have a simple explanation, but not everyone wants to believe it. AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster Calum Lister Matheson, University of Pittsburgh Contrails have a simple explanation, but not everyone wants to believe it. AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster Calum Lister Matheson, University of Pittsburgh

Everyone has looked up at the clouds and seen faces, animals, objects. Human brains are hardwired for this kind of whimsy. But some people – perhaps a surprising number – look to the sky and see government plots and wicked deeds written there. Conspiracy theorists say that contrails – long streaks of condensation left by aircraft – are actually chemtrails, clouds of chemical or biological agents dumped on the unsuspecting public for nefarious purposes. Different motives are ascribed, from weather control to mass poisoning.

The chemtrails theory has circulated since 1996, when conspiracy theorists misinterpreted a U.S. Air Force research paper about weather modification, a valid topic of research. Social media and conservative news outlets have since magnified the conspiracy theory. One recent study notes that X, formerly Twitter, is a particularly active node of this “broad online community of conspiracy.”

I’m a communications researcher who studies conspiracy theories. The thoroughly debunked chemtrails theory provides a textbook example of how conspiracy theories work.

Boosted into the stratosphere

Conservative pundit Tucker Carlson, whose podcast averages over a million viewers per episode, recently interviewed Dane Wigington, a longtime opponent of what he calls “geoengineering.” While the interview has been extensively discredited and mocked in other media coverage, it is only one example of the spike in chemtrail belief.

Although chemtrail belief spans the political spectrum, it is particularly evident in Republican circles. U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has professed his support for the theory. U.S. Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene of Georgia has written legislation to ban chemical weather control, and many state legislatures have done the same.

Online influencers with millions of followers have promoted what was once a fringe theory to a large audience. It finds a ready audience among climate change deniers and anti-deep state agitators who fear government mind control.

Read more...

7 comments

Posted on 30 November 2025 by BaerbelW, Doug Bostrom

A listing of 28 news and opinion articles we found interesting and shared on social media during the past week: Sun, November 23, 2025 thru Sat, November 29, 2025.

Stories we promoted this week, by category:

International Climate Conferences and Agreements (8 articles)

- Bad COP Personal Blog, Michael E. Mann, Nov. 22, 2025.

- COP30: Key outcomes agreed at the UN climate talks in Belém A voluntary plan to curb fossil fuels, a goal to triple adaptation finance and new efforts to “strengthen” climate targets have been launched at the COP30 climate summit in Brazil. Carbon Brief, Carbon Brief Staff, Nov 23, 2025.

- UN warns world losing climate battle but fragile Cop30 deal keeps up the fight Reaching agreement in divisive political landscape shows ‘climate cooperation is alive and kicking’, says UN climate chief. The Guardian, Damian Carrington, Oliver Milman, Jonathan Watts and Damien Gayle, Nov 23, 2025.

- The Guardian view on UN climate talks: they reveal how little time is left | Editorial Editorial: A fragile Cop30 consensus is a win. But only a real bargain between rich and poor nations can weather the climate shocks that are coming The Guardian, Editorial, Nov 24, 2025.

- I didn't wanna make a COP30 video Dr Gilbz on Youtube, Ella Gilbert, Nov 24, 2025.

- Here are 3 big ideas to combat climate change, with or without COP As the U.N.’s COP30 meeting falls short, groups find ways to fight climate change on their own Science News, Carolyn Gramling, Nov 26, 2025.

- World off track on climate action amid fossil fuel crisis: Expert The United Nations climate talks in Brazil reached a subdued agreement recently that pledged more funding for countries to adapt to the wrath of extreme weather Latest News, Press Trust of India, Nov 27, 2025.

- Revealed: Leak casts doubt on COP30’s ‘informal list’ of fossil-fuel roadmap opponents A confused – and, at times, contradictory – story has emerged about precisely which countries and negotiating blocs were opposed to a much-discussed “roadmap” deal at COP30 on “transitioning away from fossil fuels”. Carbon Brief, Carbon Brief Team, Nov 28, 2025.

Climate Change Impacts (7 articles)

- Scorching Saturdays: The rising heat threat inside football stadiums Excessive heat and more frequent medical incidents at college football stadiums in the South could be a warning sign for universities across the country. Grist, Lee Hedgepeth, Inside Climate News, Nov 24, 2025.

- Climate change could expand habitats for malaria mosquitoes, researchers warn Phys.org, University of Copenhagen, Nov 26, 2025.

- Emergency response needed to prevent climate breakdown, warn experts Scientists sounded the alarm on the dire consequences of continued inaction at a briefing in London, warning that we could be heading for "unprecedented societal and ecological collapse" New Scientist - Home, Michael LePage, Nov 27, 2025.

- Scientists warn half the world`s beaches could disappear Rising seas and human pressures are rapidly shrinking the world’s beaches and destabilizing the ecosystems that depend on them. Science Daily, undação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo, Nov 27, 2025.

- Africa`s forests transformed from carbon sink to carbon source, study finds Alarming shift since 2010 means planet’s three main rainforest regions now contribute to climate breakdown The Guardian, Jonathan Watts, Nov 28, 2025.

- Revealed: Europe`s water reserves drying up due to climate breakdown Exclusive: UCL scientists find large swathes of southern Europe are drying up, with ‘far-reaching’ implications The Guardian, Rachel Salvidge, Nov 29, 2025.

- `We had to swim to safety. I didn`t think we would make it out alive`: the people fleeing climate breakdown - in pictures Photographers Mathias Braschler and Monika Fischer capture the families, farmers and fishers who have been forced to leave their homes by extreme weather – and the landscapes they left behind. Introduction by Dina Nayeri The Guardian, Dina Niyeri with Mathias Braschler and Monika Fischer , Nov 29, 2025.

Read more...

0 comments

Posted on 27 November 2025 by Doug Bostrom, Marc Kodack

Open access notables

Observed large-scale and deep-reaching compound ocean state changes over the past 60 years, Tan et al., Nature Climate Change

Multiple climate-related stressors affect the ocean, including warming, acidification, deoxygenation and variations in salinity, with profound effects on Earth system cycles, marine ecosystems and human well-being. Nevertheless, a global perspective on the combined impacts of these changes on both surface and subsurface ocean conditions remains unclear. Here, applying a time-of-emergence methodology to observed physical and biogeochemical variables, collectively referred to as compound climatic impact-drivers, we show individual and compound ocean state changes have become increasingly prominent globally over the past 60 years. In particular, observations show the simultaneous emergence of compound climatic impact-drivers in regions spanning the subtropical and tropical Atlantic, the subtropical Pacific, the Arabian Sea and the Mediterranean Sea. We highlight extensive exposure of different ocean layers to compound emergence, characterized by significant intensity, duration and magnitude. These results provide a comprehensive framework and perspective to illustrate the ocean’s vulnerability to pervasive and interconnected changes in a warming climate.

Growing Risk of Soil Salinization Linked to Soil Droughts in a Changing Climate, Li & Wang, Geophysical Research Letters

Soil salinity and soil drought are primary global threats to cultivated land and crop productivity, yet their interrelationships and responses to a changing climate remain unclear. This study investigates the global distribution and long-term trends of soil salinity, as well as its relationships with soil droughts from 1980 to 2018. Our findings reveal that 14.73% of global soils have experienced a significant increase in salinity. The increasing trend of soil salinity is closely linked to changes in soil drought patterns, particularly the increased total number of drought days. Critically, long-term drought events (>6 months) play a key role in the transition from non-saline to saline soil, setting the stage for the formation of saline soils in 6.78% of the world's dry regions. This study highlights a growing risk of soil salinization and provides critical insights for assessing soil vulnerability to degradation in the face of persistent droughts.

Visualizing Climate Change in an Era of A.I. Slop: How Chatbot Image Generator Models Distort the Climate Crisis in Public Imagination(s), Hopke, Emerging Media

Climate change has long been difficult to visualize, contributing to climate inaction. Critical visual methods are used to analyze the social constructions of climate change encoded within leading generative A.I. chatbot text-to-image large language models: OpenAI's DALL·E 3 and Google Gemini's Imagen 2 and Imagen 3. Synthetic data for two types of generative A.I. climate change imagery are examined: (1) still images generated using generic climate change prompts and (2) images generated about heat wave impacts on people. Findings show that polar bears are a consistent visual metaphor for the climate crisis in images created with DALL·E 3 and that the model distorts climate change extreme heat risks. Google Gemini's Imagen models generated more photorealistic climate visuals somewhat grounded in climate science with greater safeguards built-in for the generation of humanoid figures and depictions of human suffering. As this research shows, generative A.I. visual outputs are reflective of the biases actively encoded into text-to-image models through data training sets and programming decisions. It is argued that chatbot image generator models distort the climate crisis in public imaginations by replicating pre-existing visual (mis-)representations of climate risks.

Multifaceted polarization and information reliability in climate change discussions on social media platforms, Bassolas et al., Royal Society Open Science

Social media platforms like YouTube and Twitter play a key role in disseminating both reliable and unreliable information about climate change. This study analyses the topology of interactions in Twitter and their relation to cross-platform sharing, content discussions and emotional responses. We examined climate change discussions across four topics: the 27th United Nations Climate Change Conference, the Sixth Assessment Report of the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Climate Refugees and Doñana Natural Park. While retweets reinforce in-group cohesion in the form of echo chambers, inter-group exposure is significant through mentions, suggesting that exposure to opposing views intensifies polarization, rather than mitigates it. Ideological divides feature content differences accompanied by steeper negative sentiments, especially from right-leaning communities prone to share low-reliability information. We identified a topological and thematic alignment between platforms, indicating that ideological communities are interconnected across them. Our findings show that climate change polarization is multifaceted, involving ideological divides, structural isolation and emotional engagement. These results suggest that effective climate policy discussions must address the emotional and identity-driven nature of public discourse and seek strategies to bridge ideological divides.

From this week's government/NGO section:

A 2,900% Increase in Greenwash: Big Oil Targeted Brazil With Google Ads To Undermine COP30, Climate Action Against Disinformation, C3DS, and Climainfo

The authors analyze digital greenwashing by major oil companies, focusing on their use of Google Ads in the months leading up to COP30. Globally, oil company ads on Google spiked by 218% in October 2025, while ads targeting Brazil increased by 2,900%. The oil sector’s biggest users of Google Ads saw particularly large increases: Saudi Aramco expanded its adverts by 469.2% month-on-month in October, TotalEnergies by 106.5%, and ExxonMobil by 156.3%. BP made the biggest jump in adverts bought at 1,369.2%, from a low base. For adverts shown in Brazil, Petrobras stands out, accounting for almost 70% of total Google Ads, with 665 published in 2025, a considerable increase from the four months before the COP30. To combat the oil industry's disinformation strategy, it is essential to increase regulatory intervention, including a potential ban on fossil fuel advertising, as well as enhance enforcement and improve transparency and data on digital greenwashing.

Counting the Cost: Quantifying the Rising Impacts of Heat-Related Productivity Losses in the United States (2001–2023) Authors, Clark et al., Nicholas Institute for Energy, Environment & Sustainability, Duke University

Extreme heat is increasingly recognized as a major threat to workers' health and economic productivity. The authors quantify how rising temperatures have eroded US economic productivity over the past two decades, especially in heat-exposed industries. Using high-resolution hourly weather data and multiple labor productivity models, the authors estimate that heat-related productivity losses grew from a model average of $130 billion in 2001 to $220 billion in 2023. These losses have been concentrated in sectors with relatively high exposure to heat, with the construction and manufacturing sectors facing the highest average annual losses—though all sectors have been affected. Geographically, heat has disproportionately affected rural Southern counties, where average annual heat-related losses often exceed 3% of total county gross domestic product. The study sheds new light on heat-economy interactions, showing how both modeling assumptions and local conditions significantly affect estimated impacts, providing critical insights for developing targeted adaptation strategies.

156 articles in 57 journals by 1028 contributing authors

Physical science of climate change, effects

Alpine Summer Surface Temperature Amplification Is Spatially Heterogeneous and Intensified by Wind and Sun, MacDonald et al., Ecology and Evolution Open Access 10.1002/ece3.72542

Conditions for instability in the climate–carbon cycle system, Clarke et al., Earth System Dynamics Open Access 10.5194/esd-16-2087-2025

Eurasian winter temperature variability amplified by synoptic-scale arctic warming and the corresponding sea ice responses, Zhang et al., Global and Planetary Change 10.1016/j.gloplacha.2025.105188

Read more...

0 comments

Posted on 26 November 2025 by Zeke Hausfather

This is a re-post from The Climate Brink

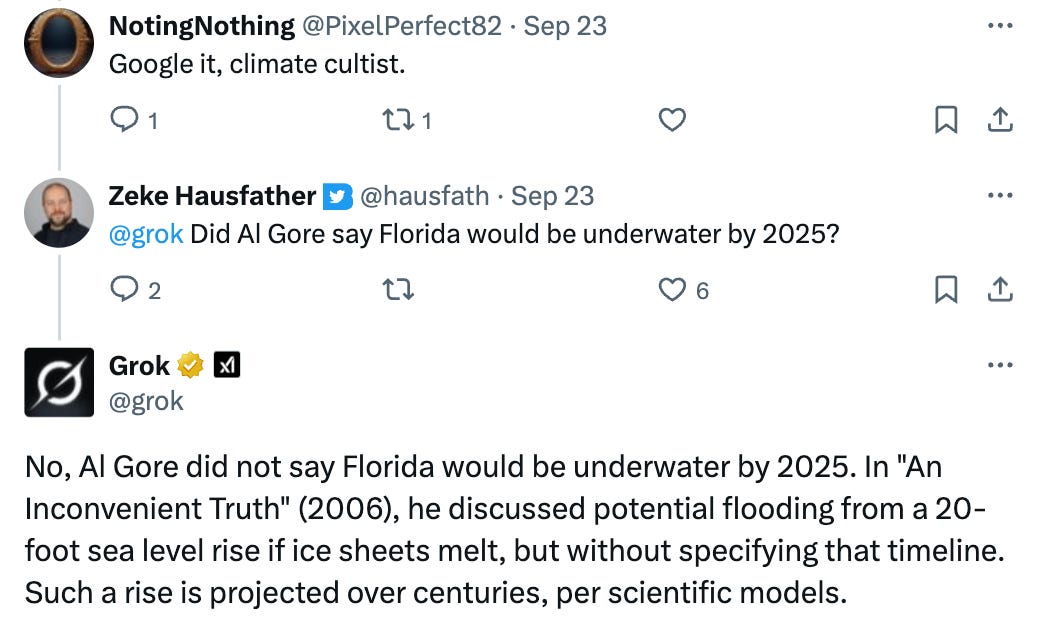

I still spend a decent amount of time engaging with folks who disagree with me on X (nee Twitter). One thing there has recently caught my eye is the integration of Grok, xAI’s large language model (LLM), into twitter engagements. Users can ask Grok questions and get answers, and in many cases (particularly for scientific questions) these answers are not necessarily what they are looking for:

Grok is somewhat of an outlier in the LLM space as its developers have tried to manipulate its outputs to fit their ideological priors (with some unfortunate results). But even Grok is surprisingly consistent at giving scientifically accurate answers to questions about topics like climate change, vaccines, evolution, GMOs, and others where the US public tends to be divided along ideological lines.

|

|

The Consensus Project Website

THE ESCALATOR

(free to republish)

|

Arguments

Arguments

The recent pause in Arctic sea-ice loss is natural variability on top of a long-term, human-driven decline.

The recent pause in Arctic sea-ice loss is natural variability on top of a long-term, human-driven decline. Contrails have a simple explanation, but not everyone wants to believe it.

Contrails have a simple explanation, but not everyone wants to believe it.