Economic Growth and Climate Change Part 2 - Sustainable Growth - An Economic Oxymoron?

Posted on 29 November 2011 by perseus

In part 1 we examined the principal economic factors which determine anthropogenic CO2 emissions from the combustion of fossil fuels. In this section we examine the potential for reductions in each of these terms.

As a reminder the economic factors determining CO2 can be described by the Kaya identity:

CO2 ≡ population x [energy/GDP] x [CO2 /energy] x [GDP/population]

Where energy refers to primary energy, energy/GDP is called the energy intensity, CO2/energy the carbon intensity, GDP/population the (economic) output per capita and GDP the gross national product. So this reduces to:

CO2 ≡ population x energy intensity x carbon intensity x output per capita

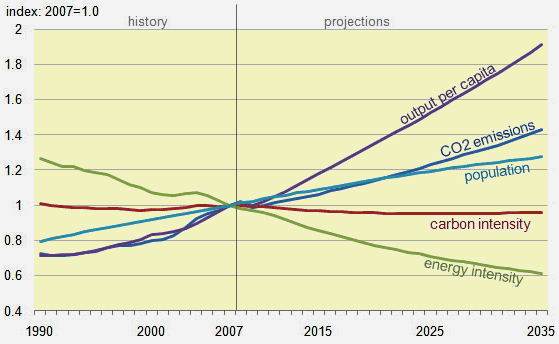

The global trends in each of these terms from 1990 to 2007 and projections from 2007 to 2035 assuming a 'business as usual' scenario are illustrated below.

Source: International Energy Outlook 2010 (original source: US Energy Administration Information)

Between 2007 and 2035, energy intensity and carbon intensity are expected to reduce by about 39% and 4%. In contrast population and economic output per capita is expected to increase by 27% and an alarming 91% respectively. All these factors together will increase CO2 emissions by around 42%. Therefore, it appears that if we carry on as normal, economic growth will swamp any benefit attained though technological advances, resulting in a substantial increase in CO2.

To meet CO2 targets, many mainstream politicians and economists such as Nicolas Stern talk about ‘decoupling the relationship between carbon emissions and economic growth by reducing carbon and energy intensity so we can carry on increasing GDP. Stern estimated in 2006 that the annual costs of achieving stabilisation between 500 and 550ppm Carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) is around 1% of global GDP if we start to take strong action now.

However, this concentration is too high. A stabilisation target of 450 parts per million CO2e is more widely regarded as synonymous with keeping mean global temperature by 2100 at no more than 2°C above pre-industrial levels. Exceeding this would likely result in more severe consequences on human and ecological systems, although even this concentration may be too high. The figure of 450ppm CO2e requires that developed countries need to reduce GHG emissions 25- 40% below 1990 levels by 2020, and 80-95% below 1990 levels by 2050.1

Not surprisingly, a number of academics have suggested that economic growth is the main factor which needs to be addressed. For example, Professor Tim Jackson considers that economic growth “is totally at odds with the finite resource base and the fragile ecology on which we depend for survival”. In his book ‘Prosperity Without Growth’ Jackson calculates how much we would need to reduce the product of energy intensity and carbon intensity (in units of CO2e/economic output) to meet a CO2e of 450 ppm by 2050 without adjusting GDP or population growth rates. In the absence of such controls, we would need to reduce this factor by 10 times faster than the present rate, that is a 21 fold improvement by that date relative to the present to meet this target! Some other scenarios regarding population or GDP growth would require a virtual complete de-carbonisation of our entire energy system.

Recent evidence suggests that there has been limited ‘progress’ in reducing global CO2 except for a unintended temporary drop in 2009 which coincided with the economic recession, with the upward trend quickly resuming in 2010. Whilst it is difficult for rapidly expanding economies to reduce CO2 in absolute terms, it is more reasonable to expect that their CO2/GDP reduces as inefficient industries are improved or replaced. However, even these hopes were dashed in the case of China when a recent study suggested that the downward trend in this metric had reversed. To underline these figures a statement at the 2009 Copenhagen Climate Science Congress said that "recent observations confirm that given high rates of observed emissions the worst-case IPCC scenario trajectories (or even worse) are being realised."

There are also non-climate related factors to consider when examining the implications of economic growth. These include our finite resource limits, local ecological impacts, and in affluent nations the limited societal benefits of increasing incomes still further.

In conclusion, it seems that our present economic policies seem to place far too much reliance on technological methods to stand a reasonable chance of meeting future greenhouse gas targets in time. In view of the rapid pace of climate change, the risk of passing critical tipping points and the immense potential for increased global greenhouse gas emissions, a different set of policies are required. It is suggested that a multi-faceted approach would be far more effective aimed at reducing each of the terms in the Kaya Identity. This would incorporate:

-

stabilising economic activity once a country has achieved high income status

-

reducing fertility rates and increasing generational gaps in cultures with projected high population growth,

-

continuing to reduce energy intensity and,

-

encouraging more substantial reductions in carbon intensity through a wide variety of technological measures

1 see IPCC AR4 WGIII. Climate Change 2007: Mitigation of Climate Change. WGIII Contribution to the IPCC AR4 (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2007), chapter 13, Box 13.7 on page 776.

Arguments

Arguments

[DB] Please restrict image widths to 500 pixels or less.