Holistic Management can reverse Climate Change

What the science says...

| Select a level... |

Basic

Basic

|

Advanced

Advanced

| |||

|

Holistic Management is not a solution to the problem of increasing carbon emissions and climate change. Soils managed holistically show no significant boost in productivity or overall storage of carbon over a long period of time. Holistic Management offers no advantage over other similar grazing techniques in use today. |

|||||

Climate Myth...

Holistic Management can reverse Climate Change

“Holistic management as a planned grazing strategy is able to reverse desertification and sequester atmospheric carbon dioxide into soil, reducing atmospheric carbon dioxide levels to pre-industrial levels in a period of forty years.” (Allan Savory, 2014)

Holistic Management is a form of grazing management that has become popularised in recent years by Allan Savory, founder of the Savory Institute. The management technique has been subject of international attention, mainly due to the infamous TED talk that Savory gave in 2014. Savory preaches that Holistic Management, applied to most of the world’s grassland, can increase productivity of farms and reverse climate change. His explanation is that livestock, grouped in large herds, will ‘mimic nature’ and increase plant growth because of this. The increased plant growth will then, according the Savory, be able to store a great deal of carbon into soil by taking the carbon out of the atmosphere, thus reducing the level of carbon dioxide contributing to the greenhouse effect. He claims all of this can be achieved in 40 years.

Quite simply, it is not possible to increase productivity, increase numbers of cattle and store carbon using any grazing strategy, never-mind Holistic Management. There are several factors which are important in controlling the ability of soils to store carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. A list of these factors, and their importance and relevance to Holistic Management, is listed here:

The Carbon Cycle

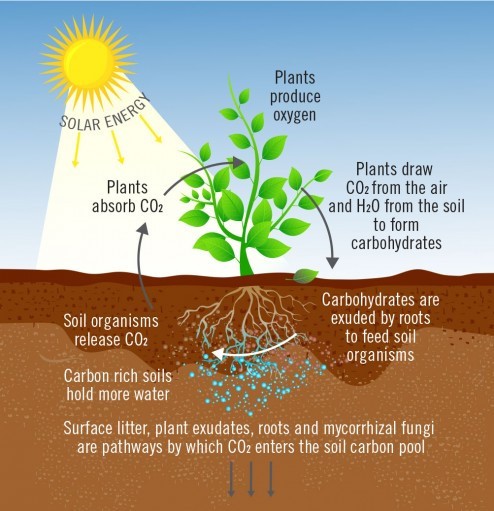

Processes such as photosynthesis, plant respiration and bacterial respiration are all part of the cycle of carbon in and out of the atmosphere. Levels of each process determine if the carbon is stored in soil, used or is released. Plants, for example, depend on carbon for growth. In photosynthesis, energy from the sun allows plants to extract carbon dioxide in the atmosphere for its own growth, producing oxygen as a waste product. The additional carbon not used for growth is stored in soil as something called humus, which gives soil its volcanic colour. The darker the colour of the deep soil, the increased level of soil organic carbon (SOC). SOC will be increased if the level of photosynthesis is high but is also dependent on the presence of soil microbes and nutrients. The level of SOC determines soil quality and potential to store even more carbon (Ontl & Schulte 2012, Figure 1).

Figure 1: A simple version of the carbon cycle, related to how plants cycle carbon for growth, release, and storage. Source: https://ecosciencewire.com/2016/06/09/the-hurdles-to-carbon-farming/

However, stored carbon can also be lost from soils. Damage to soils, like erosion and increased decomposition, leads to an overall loss of carbon, where their potential of the soil to store carbon is outweighed by carbon losses. This carbon seeps from the soil back into the atmosphere, further increasing the greenhouse effect.

Carbon losses over time

Applying a new grazing technique on grasslands which have been mismanaged may indeed have positive results in terms of soil carbon storage during the first few years. But the main problem is that storage slows after the initial change, and over a long period of time (such as 50 years), the storage potential of the soil is maximised as it approaches an equilibrium (Nordborg, 2016). This effect is more observable in dry regions of the planet. This is because dry regions have lost much of their soil content, therefore having low carbon storage potential. They are at risk of completely drying out because of increasing temperatures and more at risk to the detrimental effect of mismanaged grazing (Lal, 2004).This makes it unreasonable to apply Holistic Management to such dry areas, where the intense grazing would no doubt leave soils further damaged. In fact, one of the principals of Holistic Management - focusing on using the intense hoof action of cattle – has been claimed by the Savory Institute to increase the absorption of water by soils. However, several studies in fact stated that the opposite effect was seen. When comparing land that was not grazed with land that had been managed using a short rotational grazing system (which is very similar to Holistic Management in its ideas), water infiltration was significantly reduced, and the hoof action did not improve incorporation of litter into soil (Dormaar et al. 1989, Holechek et al. 2000).

Long term studies on the effect of grazing on soil carbon storage have been done before, and the results are not promising. Two studies – by Bellamy (2005) and Schrumpf (2011) – studied soil carbon data and soil organic carbon, respectively, over periods of 25 years and a range of 10-50 years in European grasslands. Bellamy’s study came to the conclusion that there was no significant change in soil organic carbon stocks over this long period of time, and Schrumpf’s study showed that as an overall, there was no clear pattern in carbon storage. Increases and decreases were observed, as well as times of stability. There was no overall pattern to suggest that grazing had any sort of positive effect on carbon storage.

Increasing temperature

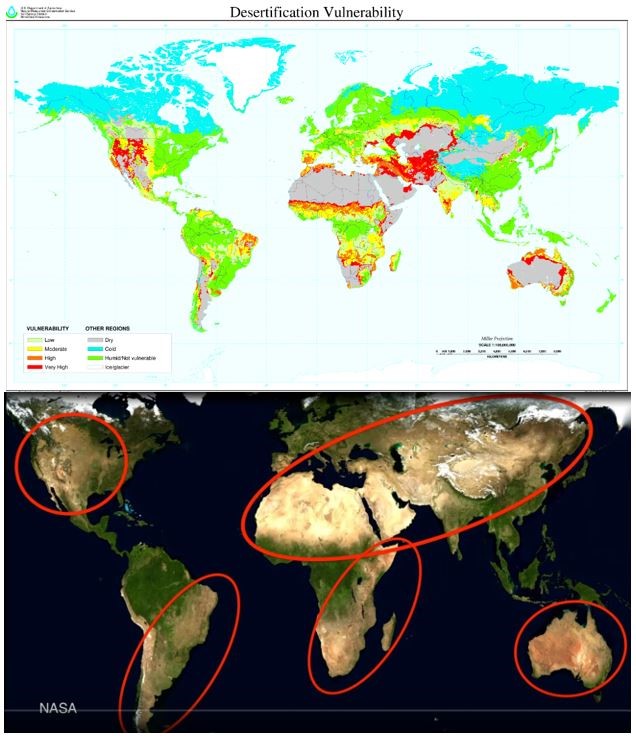

Allan Savoury wants to expand Holistic Management to cover land across the globe, that he believes can be saved from complete desertification by using his grazing technique. Simply, this is not possible due to the variety of climates that exist around the world, and in many cases, land which he has highlighted as targets to save by his technique cannot support livestock. This is clear in Figure 2:

Figure 2:

Top: A view of the world’s land and their vulnerability to desertification by climate change. Points to note are the land in grey – which is already dry – and the red / orange areas which at a high risk. Source: https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/detail/national/nedc/training/soil/?cid=nrcs142p2_054003

Bottom: The land that Savory highlights at land that is desertifying, taken from his TED talk. Note the difference between the correct figure (above) and Savory’s “estimate”. Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vpTHi7O66pI&t=255s

To expand on this, land which is already desert, such as the Sahara, cannot be revived by any management technique. The climate is too harsh, cannot support plant growth, and therefore cannot support livestock. This is the same case for land which is at high risk of desertification, in countries such as Iran and Iraq (Figure 2). This leaves semi-arid and humid land as the only potential land able to support livestock. Climate change is likely to further damage these soils further. The explanation is that, as temperature increases, soil becomes drier. The soil becomes vulnerable to erosion, less likely to retain water, and levels of soil organic content will go down as the soil gets drier (Dalias et al. 2001). The carbon will seep out from soil back into the atmosphere. The soil changes from a carbon “sink” to a carbon “source”. In turn, this affects livestock. As the plant productivity gets worse, the livestock have less to feed on, and overall productivity of the farm goes down.

Methane

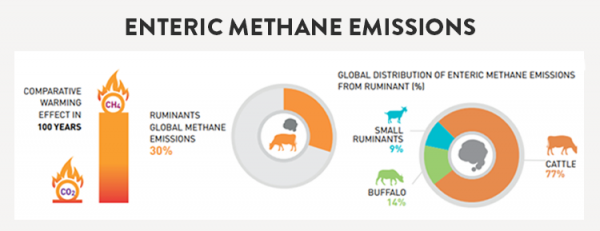

Methane, CH4, is a potent greenhouse gas. It is capable of trapping heat in the atmosphere, like carbon dioxide, and is a significant factor in global warming. Melting permafrost, methane clathrates in ocean and mostly importantly emissions from livestock are responsible for a large proportion of methane that has been released into the atmosphere. When cows burp or excrete gas, they release methane (Figure 3). This methane then accumulates in the atmosphere for a period of around 12 years before it is broken down into water vapour and carbon dioxide, which are both greenhouse gases themselves (Ripple et al. 2014). As methane has a shorter atmospheric lifetime than carbon dioxide, its global warming potential is 28 times higher (Shindell et al. 2009). Part of the problem is that as the human population grows, the demand for meat grows too. At the time of writing, the population of livestock (ruminants) is increasing by 25 million per year (FAO). This has the knock-on effect of increased methane emissions, and further global warming.

Allan Savory has refused to put a limit on the number of livestock that a farm can accommodate using the Holistic Management practice, claiming that bacteria capable of breaking down methane will solve this problem. He also has claimed that the number of wild ruminants in the past is equal to the current number of domesticated ruminants. This is inaccurate. The level of methane in the atmosphere today is 2.5 times higher than the level recorded before the industrial revolution (IPCC, 2001). This number has certainly increased as result of the expansion of the meat industry, in addition to other reasons listed. The methane-eating bacteria are common in both oxygen rich and oxygen depleted environments but are certainly not capable of breaking down the huge pool of methane that is present in the atmosphere today.

Figure 3: The Methane Emissions which are attributable to cattle. Note the increased warming effect of methane over a 100-year time scale, compared to carbon dioxide. Source: http://www.ccacoalition.org/en/activity/enteric-fermentation

Overall, methane emissions have continued to rise at an unprecedented rate over the past 250 years. Reducing livestock-based methane emissions will have a positive effect on global warming. For Holistic Management to work, there must be a balance between the amount of methane produced by livestock and the amount of carbon stored, which is known to be small.

Conclusions

Because of the complex nature of carbon storage in soils, increasing global temperature, risk of desertification and methane emissions from livestock, it is unlikely that Holistic Management, or any management technique, can reverse climate change. Studies of several grazing techniques and carbon storage have produced no ground-breaking results to suggest that Savory’s idea is doable. With increasing temperature, the ability of soil to store carbon will decrease, and grazing will likely speed up the process of desertification. Finally, methane emissions from cattle are currently too high, and their effect on global warming cannot be ignored. Adding more livestock to the planet will not help this.

References

Bellamy, P.H. et al., 2005. Carbon losses from all soils across England and Wales 1978-2003. Nature, 437(7056), pp.245–248.

Dalias, P. et al., 2001. Long-term effects of temperature on carbon mineralisation processes. Soil biology & biochemistry, 33(7), pp.1049–1057.

Holechek, J.L. et al., 2000. Short-duration grazing: the facts in 1999. Rangelands Archives, 22(1), pp.18–22.

Johan F. Dormaar, Smoliak, S. & Walter D. Willms, 1989. Vegetation and Soil Responses to Short-Duration Grazing on Fescue Grasslands. Journal of Range Management, 42(3), pp.252–256.

Lal, R., 2004. Soil carbon sequestration to mitigate climate change. Geoderma, 123(1), pp.1–22.

Monica Petri, Caterina Batello, Ricardo Villani and Freddy Nachtergaele, 2009. Carbon status and carbon sequestration potential in the world’s grasslands. FAO. Available at: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i1880e.pdf.

Nordborg, M., 2016. A critical review of Allan Savory’s grazing method. SLU/EPOK – Centre for Organic Food & Farming & Chalmers. Available at: http://publications.lib.chalmers.se/records/fulltext/244566/local_244566.pdf.

Ontl, T.A. & Schulte, L.A., 2012. Soil carbon storage. Nature Education Knowledge, 3, p.3(10):35.

Schrumpf, M. et al., 2011. How accurately can soil organic carbon stocks and stock changes be quantified by soil inventories? Biogeosciences , 8(5), pp.1193–1212.

Shindell, D.T. et al., 2009. Improved attribution of climate forcing to emissions. Science, 326(5953), pp.716–718.

Thornes, J.E., 2002. IPCC, 2001: Climate change 2001: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability, Contribution of Working Group II to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by J. J. McCarthy, O. F. Canziani, N. A. Leary, D. J. Dokken a: BOOK REVIEW. International Journal of Climatology, 22(10), pp.1285–1286.

Last updated on by Seb V . View Archives

Arguments

Arguments

RedBaron @25, apology accepted, but find the social graces man. Anyone can do it!

I have had to learn to be a bit diplomatic , because my job involved getting clients although I'm semi retired now. Yeah its tedious, and I prefer to get to the point myself, but if you want to criticise peoples comments, its useful to find at least some points of agreement etc, and smooth the waters, and be nice. If you don't, people will get annoyed and possibly dismiss you and your ideas. It's human nature.

I was basically supporting you, in the main.

You said I was in denial about proper rotational grazing sequestering carbon when I plainly wasn't. I stated that poor farming practices contributed to higher emissions and we should graze cattle in ways that promote plant growth. I didn't have time to go into more details about liquid carbon pathways, and I thought this pathway was activated when grass growth was stimulated, but not over stimulated.

I was really looking for some confirmation that the reason the IPCC says we have a methane emissions problem with cattle, is because numbers of cattle have increased at the same time that poor farming practices have degraded soil sinks and we have deforstation. Is that broadly correct in your opinion?

Please note I said cattle grazing is carbon neutral "all other things being equal" and then went on to explain that they are not equal because we have farmed poorly and degraded natural sinks.

However in hindsight I do accept your point that carbon neutral was bad wording because the times it would be exactly carbon neutral are limited.

Perhaps I could have said it better, something like this: "Cattle emit methane that breaks down to carbon dioxide and this is normally absorbed by natural sinks such as grasses and trees, but in recent decades we have increased cattle farming and degraded natural sinks with deforestation and poor farming practices, thus leading to an excess of atmospheric CO2 . The solution is to reduce our meat consumption and plant trees and farm in ways that enhance the ability of soils to absorb carbon. Proper rotational grazing can enhance the ability of grasslands to absorb carbon, so there is no need to completely stop eating meat."

This needs polishing up, but you have to keep it simple like this so the public get the big picture. You can then go on to explain the details of liquid carbon pathways. Hope that helps.

@Nigelj,

Glad we are talking again, but you are still completely wrong. I am not sure how overly simplified I need to make this....

If something is beneficial, we need more of it. If something is harmful, we need less of it. Is this simplified enough for you? I am proposing eliminating many harmful practises in agriculture, and increasing many beneficial practises.

It makes no sense at all to go through all the trouble of changing agriculture to regenerative practices, then reduce our usage of those beneficial systems. You got it backwards.

You said, "The solution is to reduce our meat consumption and plant trees and farm in ways that enhance the ability of soils to absorb carbon. Proper rotational grazing can enhance the ability of grasslands to absorb carbon, so there is no need to completely stop eating meat."

That's backwards. It makes sense only if we DONT change agriculture.

Actually we need to increase meat production significantly. Global hunger and cronic malnutrition affects 815 million people (Food and Agriculture Organization [FAO] et al., 2017) As developing nations pull themselves out of poverty, they can afford more meat in their diet and balance their nutritional requirements much better.

The thing that needs to be dramatically reduced is commodity crops used to make biofuels and supply feedlots and other factory farms, make high processed foods like high fructose corn syrup etc... Cornfields need switched to forests and grasslands depending on the biome that was destroyed to make the cornfield. We can then actually raise more animals than now, cheaper, healthier, and beneficial to the newly restored environments we are now raising them in instead of CAFOs.

This would increase the meat supply significantly and drive the price down too. Especially if the ranchers and farmers got paid for the increases of soil carbon.

Its a win win all around for everyone.

It’s Time to Rethink America’s Corn System

RedBaron @27

You have made a sweeping statement that I got everything wrong. You have learned literally nothing about my comments about diplomacy. Most people are going to react to that sort of comment by dismissing both you are your ideas. Fortunately for you I have a thick skin and control my temper.

It's also an immensely silly statement, because some things I said are what you have said, or close enough.

You have not answered my question in paragraph 5. Again, you show no diplomacy, and no respect.

You have mentioned one specific thing that you disagree with: that I think we should eat less meat. You think we should eat more meat, but this doesn't make sense to me, because it means we need even more land for cattle. Do you not realise there is competing demand for land for biofuels, and beccs and foresty, and crops to feed a population heading to 12 billion people at least, and urban development?

Meat is a very inefficient use of resources requiring enormous inputs of land, biomass and water for a small quantity ofprotein outputs. Obviously you must know this.

Yes I understand the "corn" issue in America, but that is only one component of land demand as I've outlined.

It's really unlikely we can or should expand areas of land for grazing. Given rotational grazing is land intensive, if anything per capita meat consumption probably thus needs to fall, although not drastically.

Now you would presumably argue that actually hugely expanding grasslands for cattle farming is a great thing, because it draws down atmospheric carbon, and so this should all take precedence over everything else. This would be a big claim so needs massive levels of proof. I have had a look at the numbers, and even taking your best numbers of 5-20 tonnes CO2e/ha/yr, and using 10 tonnes, this gives something like a reduction in about 10% of our total current emissions per year It's still a good number - but as pointed out on this website about a year ago it falls well short of the sort of claims made by people like Savory no matter how you try to spin it. And this assumes literally all farms work regeneratively, ( a massive scaling up operation with huge challenges) and this soil carbon diminishes over time as soils heat up and upper layers become a net carbon source.

The whole rotational grazing proposal has merit, but would therefore take a very long time to make a dent in atmospheric concentrations of carbon, so its hard for me to see a case for scaling up your proposal above current land area.

I can however see a very good case for making better use of what land area we "currently" use for livestock farming, and using Savorys rotational grazing system.

If you think my maths is wrong, by all means check it and tabulate your own calculations in an ordered fashion but my rough boe calcs and conclusions are not much different from scientists who actually specialise in this area.

I think you are in danger of coming across as an obsessive scientific crank with their pet project somewhat like Killian over at realclimate.org! Now perhaps I'm not being too diplomatic myslelf :) Imjust giving you a bit of advice.

You have posted a lot of details and links on soil science. I'm not disputing that stuff in the main and never have. So if you want to post it don't do it for my benefit, but perhaps you are doing it for other people reading.

To summarise, I do accept there is a valuable looking pathway where properly grazed pastures encourage the glomalin pathway and leads to deeper carbon rich soils ultimately, and as such we should farm that way, but the process looks slow to me, and theres not exactly a scientific consensus on the effectiveness of the issue, and there are many competing uses for land. As such its hard for me to think we should actually expand grazing lands, but rotationally grazing what we have seems logical. I think you are right in general terms, but you may need to be more realistic.

There is approximately 3.5 billion ha of grazing land already. approximately 80% of it is currently over grazed or under grazed.

10 tonnes CO2e/ha/yr x 3.5 billion = 35 billion tonnes CO2e/yr

Global emissions are in that range as in 2018, global fossil CO2 emissions totaled 36.6 billion tons.

That is not counting restoring desertified land as Savory advises, nor does it count restoring farnland currently being used unwisely for commodity crops to fill a highly wasteful and unsustainable industrialised commodity system. That's about 320 million hecares worldwide that less than 1/2 of which actually feeds human beings. So another 1.6 billion tonnes CO2e/yr.

But wait there is more. Most the haber process fertilizers and fossil fuel usage for supplying these foolish production models all add up to approximately 15-20 % of emissions worldwide. Just fixing them alone potentially reduces emissions ~7.2 billion tonnes CO2/yr.

35+1.6+7.2 = roughly a potential of 43.8 billion tonnes CO2 offset against a total emissions of 36.6 billion tonnes emissions and already about 1/2 of that is already offset by natural systems!

We have the potential for drawdown. Maybe just by using holistic management to replace the commodity corn system and regenerate desertified lands.

So I am not sure at all how you obtained a potential of only 10% since you have not shown your figures.

Of course that's theorectical potential. Much like the potential for renewable energy, the actual numbers are fairly certain to fall short of the potential. Not everyone will change agriculture in a single year. It takes decades for training and infrastructure etc... and that's only after the actual commitment to make the change in the first place.

So of course reductions in fossil fuel use will need to be made to meet it 1/2 way in the middle somewhere. But certainly actual drawdown is possible. No other drawdown potential exists using any other technology currently available.

Red Baron,

You have been making the same claims here for years. I read your references and they do not support your wild claims. The OP here reviews the literature on this topic and clearly states that your claims are not supported. A review of the comments sees you repeating the same unsupported claims.

Better farming methods will help and fix a little carbon. Your claims that all released carbon can be sequestered are simply false. There is no magic bullet in graising.

New readers should read the OP for a more balanced evaluation of holistic grazing.

@michael Sweet,

I have back up all claims as well as debunked the false claims in the OP multiple times, if that's what you mean, sure.

And yes I have done this for years, and slowly the consensus of scientific opinion has been moving this direction too.

There are many many comming around, project drawdown being a great example: Project drawdown

Terraton initiative being another.

Even the IPCC admits it, but is under the mistaken notion that changing agriculture would lower yields, so makes the mistaken assumption relatively small acreage could be changed. In fact yields for increase substantially. So that is why although they agree it could be significant, they lowball it.

Now it is to the point that the OP position posted here is decidedly minority, Actually in my opinion it is actually a merchants of doubt talking point that somehow got past Skeptical Science..

I am not critical of Skeptical Science though, because the merchants of doubt used a shotgun approach and fired literally hundreds of obfuscation attempts and the fact you managed to debunk them all but one is pretty impressive actually.

I am just trying to help you tackle the one you missed.

[DB] Sloganeering snipped.

Red Baron @29, I haven't kept a record of my calculation, but I was going by a smaller land area that I got off some website ( it looks like it was wrong), and I factored in an allowance for the fact that warming will cause some loss of soil carbon eventually as has been established in research. So my estimate was probably too low, however I doubt we would achieve your optimistic numbers either.

And like I said, there are huge competing requirements for land, and they are valid requirements. Realistically you are going to probably have to make the best of current grazing areas, and even that will be optimistic. So given rotational grazing uses more land than intensive corn fed dairy farming, its rather looks like lower meat consumption to me rather than higher meat consumption.

Savorys ideas about reclaiming desert look rather optimistic. This would not just happen in a market economy, there's not enough profit in it, and it would need massive tax payer subsidies. Again there are many competing requirements for tax payer subsidies.

However I do think theres a case for subsidising proper rotational grazing methods etc as best we can. Carbon taxes and cap and trade are too indirect to usefully promote your ideas.

So yeah the rotational grazing thing still looks very useful to me and would sequester significant carbon, but you have to be realistic about what can be achieved in the real world. Don't over hype it. Sometimes selling an idea effectively requires being just a little bit understated.

Since I have been accused of sloganeering and had my IPCC comment snipped...

Here is the IPCC report: IPCC Report: Climate Change and Land

The report states with high confidence that balanced diets featuring plant-based and sustainably produced animal-sourced food present major opportunities for adaptation and mitigation while generating significant co-benefits in terms of human health.

For context the entire paragraph

This is integrated production models, not vegan diets and not as you said "reduced meat". It specifically says integrated which to a farmer has a very specific meaning. That means rather than monocropping and using those commodity feedgrains to supply the CAFO (concentrated animal feeding operation more commonly called factory farm) system , instead the animals are returned to the farm and the land and there they can fulfill their ecosystem functions for the farmer, usually in some sort of rotational system. Also please note these changes in production and consumption "could free several Mkm2

(medium confidence) of land" This is because integrated farming systems yield much MORE food per acre, compared to the factory farming system. I will repeat, they yield more in terms of yields per acre, not less. Factory farms are only more productive in terms of yields per man hour. They do not yield more food per acre.

Every one of those points Savory has repeatedly said over and over. And yet people with no knowledge of agriculture read the exact same paragraph and conclude meat consumption must drop.

The key here is sustainably produced balanced diets. Yes in some cases that might mean less meat, in many cases around the world it actually means we need more meat to make properly balanced sustainable diets. Overall globally there are many more people who would benefit from more meat in their diet, not less. And if we change to integrated sustainably produced plant and animal foods, it will actually reduce the amount of land needed for agriculture, allowing large areas to be restored to the biomes present before human impact.

Exactly yet again what Savory both advocates and has proven in his award winning proof of concept.

“The number one public enemy is the cow. But the number one tool that can save mankind is the cow. We need every cow we can get back out on the range. It is almost criminal to have them in feedlots which are inhumane, antisocial, and environmentally and economically unsound.” Allan Savory

PS There is an elephant in the room though. Right now we have all surplus commodity grains producing biofuels. Reducing land in food production by integration of sustainably produced plant and animal foods will not actually help at all if we continue to send all commodity surpluses for biofuel and other industrial uses. So even if you were right that reduce meat consumption was needed, it would not necessarily have the impact you envision. Land would still be deforested to fill this nearly unlimited demand. Even desertified land restored by holistic management would likely soon after be put to the plow to fill the demand for biofuels and desertify all over again.

In my opinion this sort of industrial use must be either eliminated or highly discouraged or else none of the other issues will improve at all. It will become so much "shifting deck chairs on a sinking titanic". That last part is my opinion based on the current market dynamic.

RedBaron @39

There's nothing inconsistent between my comments and your IPCC cut and paste, which doesn't define what the IPCC means by integrated. I mean its all fairly general but looks right in principle.

You are giving your understanding of what integrated means. But yes ok integrated farming with less monoculture and more mixed types of farming and regenerative farming might increase meat production potential. I would need to see some published research on that. I do think regenerative farming is the way to go in general principle anyway.

(I work in a design field, but I did a couple of years in quality assurance, and its made me very critical, sceptical and nit picky as I'm sure you would appreciate. But I make no apologies for that.)

I've gone back and read my comment here : "So given rotational grazing uses more land than intensive corn fed dairy farming, its rather looks like lower meat consumption to me rather than higher meat consumption." There is no fault with this all other things being equal. The integrated farming methods you propose would offset this to at least some degree, but it doesn't make my original statement wrong in any way.

I'm all for sustainably produced diets with some meat. The minimum recommendation is 60 grams of protein per adult per day and meat is a good source of protein. But many people in western countries eat far more than this, and perhaps some people in the third world dont get 60 grams but I'm guessing this would not be widespread. 60 grams is not very much, especially as a typical piece of fillet or sirloin steak is at least 100 grams.

Vegetarianism is at the other extreme and doesn't make sense to me environmentally because we have vast tracts of grasslands that only really do suit cattle, so they would be challenging to turn into crop lands.

The thing is we do need biofuels. They are about the only way to realistically get to carbon neutral air travel and shipping. Now I'm as nervous as you about vast areas of land being vacuumed up for biofuel crops, but at least some land looks like its needed.

If rotational grazing could be guaranteed to produce near miraculous levels of drawdown of atmospheric carbon, this might be a case to put "all our eggs in that basket" and say we dont even need biofuels and growing more forests, or things like BECCS, but the picture I get from all the weight of the research and commentary and articles on this website is that rotational grazing just has moderate benefits. I think higher than the harsher critics think, but less than you think.

Red Baron,

Replying to your comment at 31:

As I said before, your links do not support your wild claims. For example, your link to Project Drawdown. To start off the page you linked does not talk about grazing at all. It is your responsibility to provide correct links.

After searching the site I found this page on managed grazing. They claim that it might be possible to remove 16.34 gigatons of CO2 by the year 2050 using managed grazing. At comment 29, you claim that managed grazing could remove 35 gigatons of CO2 per year every year until 2050. Thus you claim approximately 65 times as much carbon dioxide fixed as your reference.

The teraton initiative you linked appears to be a new project by a journalist and author. He claims that the advantages of regenerative agriculture have not been systematically measured in the past and is trying to measure how much carbon is actually fixed. All the pages I saw were about general agriculture. I could not find a page on grazing. Their calculations were all back of the napkin with no supporting science.

The teraton initiative and you both make the mistake of claiming that if you remove the extra carbon dioxide from the atmosphere the problem will be solved. Reality is worse than that. If you start to remove carbon from the atmosphere, carbon dioxide absorbed by the ocean will outgas making the problem bigger. Good luck.

You made the wild claim at the start of this discussion (lost because it was posted on another thread off topic) that in the past year or two scientists have come around to your ideas in mass. You have provided no link to even a review article, much less a summary report, to support this wild claim, not even one that does not support your claim. The references in the OP are so recent it is unimaginable that scientists would have changed their minds en masse.

We all wish that argiculture would be a magic bullet to solve AGW. Agriculture might provide a wedge or two, but many other actions will be required to turn back the problem of CO2 pollution. It does not help to motivate people to act if you falsely claim there is an easy way to solve the problem.

No nigelj no one ever said we should put all eggs in one basket. Not IPCC Not Holistic management and not me.

This apparently is a lack of communication.

Potential for a sink size and rate does not mean that will be the actual any more than a 8 oz glass of water holds exactly 8 oz of water. This is the potential should all agriculture world wide adopt holistic management.

Clearly the herculean task is in changing to regenerative practises. Very likely most the agricultural infrastructure will not change any time soon.

But it is important to understand the potential, so when we say change maybe 10% of agriculture, a very reasonable and fairly easy thing to do, then we have 10% of that total potential we can count on.

Too often people misuse the reports like the IPCC and others have put out and take numbers that have already been adjusted due to probable % of adoption, and adjust them once again! So rather than 10% we end up with people thinking 10% of 10%.

The potential is as large as total emissions and could put us in drawdown if all was changed, but it won't be all changed any more than all fossil fuel emissions eliminated.

Neither one is going to happen.

But if we meet somewhere in the middle with dramatically reduced fossil fuel emissions, the soil sink is plenty large enough and the rate of sequestration fast enough that we could reach a draw down scenaio.

Red Baron @36, my reference to all the eggs in one basket only suggested that a miraculous (like really dramatic) level of results from rotational grazing would mean not needing biofuels. I made no reference to not needing anything beyond that, like not needing renewable energy. I think I was clear. And theres no evidence of miracles being likely but there is evidence of something useful.

Since you at least appear to concede we need biofuels, this will place firm limits on land areas available for grazing, which was always my point.

I agree with the rest of your comments. I tend to think there are questions about the long term sustainability of the industrial and corporate farming model, and also intensive dairy farming, particularly using feed crops. Something looks like it has to change, and the benefits to the climate might almost be a side effect of this broader level of change, if that makes sense. When there are a lot of reasons to do something, we should mostly just do that thing. We might be looking at a longer term agricultural transformation that goes well beyond 2050.

I will leave it there, and I probably wont comment more on all this for now.

Actually I did say biofuels, forestry and beccs, to be accurate. But they form a similar group of things and are different from the renewable energy issue.

Biofuels are not good and part of the reason for AGW.

Here is even more independent confirmation that the rate of sequestration is reasonable and repeatable.

Soil Carbon Sequestration and the Soil Food Web

First a simple video made by Dr. Elaine Ingham explains what I have been posting about here for several years. Including the same rate of sequestration found all over the world well within the 5-20 tonnes CO2e/ha/yr found by Dr Christine Jones decades ago and confirmed by many others.

And now Dr David Johnson tosses his hat in the ring as yet another independant researcher obtaining results in this same range.

Carbon Sequestration A practical approach

Preliminary results from Dr David Johnson

Development of soil microbial communities for promoting

sustainability in agriculture and a global carbon fix

and a better video lecture explaining a holistic mitigation strategy that includes this ecosystem service.

Managing Soils for Soil Carbon Sequestration: Dr David Johnson on Engineering Microbiology