At a glance - Has Arctic sea ice returned to normal?

Posted on 13 February 2024 by John Mason, BaerbelW

On February 14, 2023 we announced our Rebuttal Update Project. This included an ask for feedback about the added "At a glance" section in the updated basic rebuttal versions. This weekly blog post series highlights this new section of one of the updated basic rebuttal versions and serves as a "bump" for our ask. This week features "Has Arctic sea ice returned to normal?". More will follow in the upcoming weeks. Please follow the Further Reading link at the bottom to read the full rebuttal and to join the discussion in the comment thread there.

At a glance

One of the great metrics of climate change, because it is easy to visualise, is sea-ice in the Arctic. Every year, the ice margins retreat in the northern summer, reaching a minimum extent some time in September. It then refreezes through the long, dark cold winter months, until its maximum extent is reached in March.

Arctic sea-ice has a seasonal component - so-called 'first year ice' - and the more perennial 'multi-year ice'. First-year ice is relatively thin - 30-40 centimetres is typical. Multi-year stuff is thicker - 2-4 metres and much of it is situated between the north coast of Greenland and the North Pole.

Most of the annual, seasonal decline in ice extent, observed by satellites for more than 40 years, is due to first-year ice melting: the more robust multi-year ice takes more energy to remove, but nevertheless it is in decline, too. Calculations of sea-ice volume reveal that trend.

How does sea-ice form? We all know the freezing temperature of saltwater is lower than that of freshwater, hence the spreading of rock salt on the roads on frosty winter nights. Similarly, the ocean temperature needs to fall below -1.8°C (28.8°F) for sea-ice to form. In the freezing season it starts freezing over once the upper 150 metres or so of the ocean are close to that temperature.

Melt varies a lot from one year to another. This should come as no surprise: sea-ice, being on an ocean, moves about a fair amount. Variations in ocean-currents are particularly important since if sea-ice can be 'exported' out of the Arctic, it enters what is basically a hostile environment, where it melts away to nothing. Incidentally, such floes are a lot smaller than icebergs like the one that famously destroyed the Titanic in April 1912. Such ice behemoths originate where glaciers 'calve' upon reaching the sea.

Weather is a highly variable driver of sea-ice melt. Prolonged strong winds from the right direction can cause mass-export of ice into warmer waters. Then again, winds from the south transport warm air over the Arctic Ocean, causing the melting to intensify. But they may also bring in extensive cloud-decks, blocking a lot of incoming Solar energy. No surprise then that melt seasons vary a lot from one season to another.

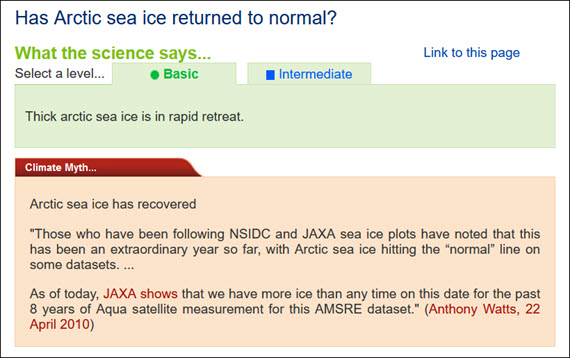

As in most things related to climate change, it's the multidecadal trend that is key and that is unequivocally downwards, both in terms of extent and volume. Sudden spurts of growth are interesting, as are record meltdowns such as that in 2012. But that's it. Trend is the critical bit. The data clearly show that since 2010, when the statement in the box above originated, eight out of the ten lowest Arctic sea-ice minima have occurred. The only two melt-seasons outside of that time-frame were in 2007 and 2008. For the big picture regarding Arctic sea-ice, ignore the noise from one year to the next and look at all the data. It's heading one way - down.

Please use this form to provide feedback about this new "At a glance" section. Read a more technical version below or dig deeper via the tabs above!

Click for Further details

In case you'd like to explore more of our recently updated rebuttals, here are the links to all of them:

If you think that projects like these rebuttal updates are a good idea, please visit our support page to contribute!

Arguments

Arguments

Comments