2010: A Year of Record Warmth and Weird Weather

Posted on 27 January 2011 by James Wight

Last year’s global temperatures are in, and the result is that 2010 is statistically tied with 2005 for the title of the warmest year since records began in 1880.

According to the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Climatic Data Center (NOAA NCDC), the global temperature for both years was 0.62°C above the 20th-century average 13.9°C; 2010 came second by a thousandth of a degree. (Climatologists usually give temperatures as anomalies relative to an average, because they are easier to compare than absolute temperatures. The last month with a temperature below average was February 1985.)

2010 set new records for the warmest March, April, May, and June. Indeed, when the seasonal cycle is removed March 2010 was the third warmest month of all time (April, May, and November 2010 were also among the top 20). The ten warmest years according to NCDC are 2005/2010, 1998, 2003/2002, 2006/2009, 2007, 2004, and 2001. The 15 warmest years have all occurred since 1995; every year since 1976 has been above average. The 2000s are the warmest decade on record, followed by the 1990s and 1980s.

2010 was the Northern Hemisphere’s warmest year and the Southern Hemisphere’s sixth warmest. The former had its warmest April, May, June, July, August, and November in 2010, while the latter had its warmest February. There was particularly strong warmth in Greenland, Canada, northern Africa, and the Middle East; as well as warmer than average temperatures in southern Africa, eastern Europe, eastern Russia, and southern Asia; and cooler than average temperatures in central Russia and northern Europe. Except for the eastern Pacific, most of the oceans were warmer than average; the North Atlantic was particularly warm.

Figure 1: Global map of regional temperature anomalies in 2010. Red dots are warm anomalies and blue dots are cool; notice there is considerably more red than blue. (Source: NOAA National Climatic Data Center.)

A year of weird weather

2010 was the world’s wettest year as well as tying for warmest, and many regions suffered devastating floods as well as terrible heatwaves. We also saw the fourth largest swing in the Southern Oscillation during a single year, beginning with a moderate-to-strong El Niño but ending with a moderate-to-strong La Niña. The latter tends to mean cooler global temperatures, yet the Earth remained hot as late as November. And all of this occurred despite the Sun being in an unusually low minimum.

The year began with an unusually cold winter in Europe, Russia, and the United States. The cold snaps were caused by the most negative Arctic Oscillation on record – basically, the continents were cold but the Arctic was hot. Meanwhile, Canada had its warmest winter, Australia had its warmest summer, and the globe had its fourth warmest January and sixth warmest February.

While conservative commentators chattered about the cold winter, global temperatures soared even higher, breaking four monthly temperature records in a row. As noted above, March 2010 not only broke the record for March but also chalked up the third warmest anomaly ever recorded. Despite the onset of La Niña around the middle of the year, we still experienced the second warmest July and third warmest August globally. The 12 months ending in July 2010 were the second warmest of the 1,561 such periods on record, and the 12 months ending in August 2010 came third.

The northern spring and summer were both the warmest on record, and many parts of Asia suffered extreme heat (in fact the year as a whole had a record number of national extreme heat records). On 26 May the town of Mohenjo-Daro in Pakistan recorded a maximum temperature of 53.5°C, the warmest temperature on the entire continent since 1942.

Russia and its neighbours suffered a record-shattering multi-month heatwave which caused 15,000 deaths, wildfires, drought, and crop failures. The daytime heat was much more intense than in the deadly European heatwave of 2003, and Moscow broke its nine-decade-old temperature record twice in a few days. Naturally it would have been a 1,000-year event, but global warming has made it eight times more likely. It’s sobering to remember that so far we’ve only had a fraction of the amount of warming we would see in a business-as-usual emissions scenario.

In a related event, the Asian monsoon occurred further west than usual, creating devastating floods which submerged 20% of Pakistan, killing 1,600 people and displacing millions – more than were affected by the 2004 tsunami.

All this was followed by the tenth warmest September. Although a cool month relative to the last decade, it would have been a near-record-breaking anomaly as recent as 1989. Arctic sea ice reached its third lowest minimum extent on record (the last four have been the four lowest) and its all-time lowest volume. This opened both Arctic shipping routes for the third consecutive time and third time in recorded history. Two expeditions successfully circumnavigated the Arctic Ocean in a single summer, something that would have been impossible just a few years earlier.

Next came the eighth warmest October. In Brazil, which suffered a severe drought throughout 2010, an important tributary of the Amazon River fell to its lowest level on record, making the Amazon itself three metres below average. And despite what was by then a strong La Niña, November 2010 was still the second warmest November globally.

December was the coolest month of 2010 (seasonally adjusted) and the seventeenth warmest December. In the Northern Hemisphere, the year ended as it began, with a strongly negative Arctic Oscillation causing more extreme cold in Europe (particularly on some insignificant island north of France whose weather has a disproportionate influence on public opinion). It’s been speculated that this unusual weather pattern might be connected to Arctic sea ice melt.

Meanwhile in the Southern Hemisphere, La Niña brought record rainfall in Queensland, Australia, flooding an area the size of France and Germany combined and capping Australia’s third wettest year on record. In January 2011, the flooding spread to capital city Brisbane, inundating over 10,000 homes and killing at least 33 people in what may be the most expensive natural disaster in Australia’s history.

The correlation of extreme heat with extreme rainfall and flooding is no surprise. As climatologist Kevin Trenberth said in June:

[T]here is a systematic influence on all of these weather events now-a-days because of the fact that there is this extra water vapor lurking around in the atmosphere than there used to be say 30 years ago. It’s about a 4% extra amount, it invigorates the storms and it’s unfortunate that the public is not associating these with the fact that this is one manifestation of climate change. And the prospects are that these kinds of things will only get bigger and worse in the future.

Independent analyses agree global warming is continuing

The NCDC results are confirmed by NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS), who also found 2010 tied with 2005 as the warmest year (only in their analysis 2010 came first by a hundredth of a degree). The ten warmest years in the GISS analysis are 2010, 2005, 2009/2007, 2002/1998, 2006/2003, 2004, and 2001. Also, according to GISS the 12-month mean record was broken several times during 2010.

All the major analyses of global temperature – by NCDC, GISS, and the British Met Office’s Hadley Centre – are in close agreement with each other. The rankings of individual years may differ, but usually within the error bars (a few hundredths of a degree). And of course, far more important than any individual year is the long-term trend, which is about 0.17°C/decade in the last 30 years. To quote a recent GISS press release:

All three records show peaks and valleys that vary in virtual sync with each other since 1880. All three show particularly rapid warming in the last few decades. And all three show the last decade is the warmest in the instrumental record.

Figure 2: Global temperature anomalies since 1880 (in one case, 1890) according to four independent analyses. (Source: NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies.)

One of the main differences between these analyses is how they extrapolate temperatures in the Arctic where there are few measurements. NCDC and Hadley implicitly assume the Arctic is warming at the same rate as the global average, while GISS assume it is warming several times faster, as is being measured by the available stations. The latter assumption makes more sense given the rapid melting of Arctic sea ice, which is making the Arctic surface less reflective. Presumably we can expect GISTEMP to continue growing warmer than NCDC and HadCRUT as Arctic sea ice continues to melt, particularly in years when it hits a record low.

Another issue is recently identified biases due to changing methods of measuring sea surface temperatures, causing global warming in the last decade to be underestimated and temperature swings in the 1940s to be overestimated. Climatologists are currently awaiting the release of a revised Hadley Centre analysis correcting for those errors. It will be interesting to see how much of a difference the corrections make.

Observed temperatures are consistent with models

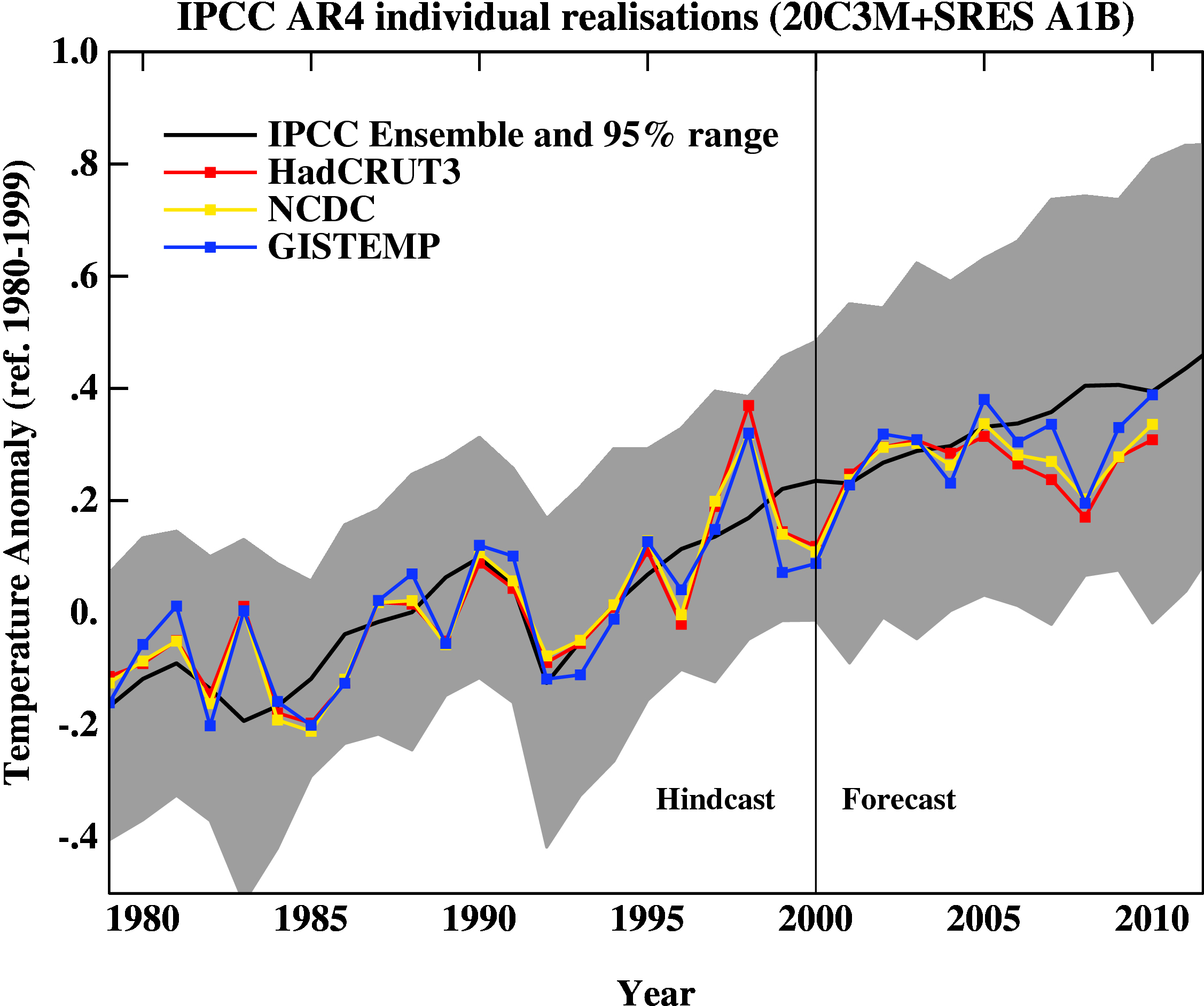

This graph from RealClimate compares the observed temperatures to the IPCC AR4 model projections for a business-as-usual emissions scenario. As you can see, observations are entirely consistent with continued global warming:

Figure 3: Observed global temperatures since 1980 compared to IPCC AR4 model projections for the business-as-usual A1B scenario. (Source: RealClimate.)

What does the future hold? In the long run the planet will continue to get warmer as it responds to skyrocketing greenhouse gas levels, by far the dominant influence on climate. The global energy imbalance varies periodically with the 11-year solar cycle, and right now the Sun is coming out of its lowest minimum for decades; but even if solar activity fell to Maunder Minimum levels, the effect would be offset by just seven years of greenhouse gas emissions. However, the global climate does vary chaotically from year to year as heat moves between the atmosphere and ocean. A few months ago, GISS predicted that with the short-term cooling influence of La Niña (expected to last into the southern autumn and maybe the southern winter), 2011 probably would not break the record of warmest year; but assuming La Niña does not last another year, it’s likely that 2012 will.

And finally, for a visual representation of how 2010 compares to other years, here is a neat graph that I made from NCDC monthly data (click to enlarge). Each line represents monthly global temperature anomalies throughout a single year, and each year is color-coded by decade. The bluer lines are years from earlier decades while the redder lines are years from later decades. The line in bold is 2010. This should give you an idea of how hot 2010 was:

This post was written by James Wight and first appeared on his blog Planet James.

Arguments

Arguments

skepticsdeniers. At least the ones I've encountered. Also note that the statement you quoted concerning speculation is also linked to a NASA news release which is here. The speculation is not without merit.liesexcuses: 'no one could have predicted this' and 'why didn't you warn us?', etc.